Rolling Stone’s 200 Greatest Australian Albums of All Time

AC/DC, 'Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap'

Written by Angus Young, Malcolm Young, and the late and great Bon Scott, Dirty Deeds was undeniably the album that shocked conservative parents as their kids rocked out to its aggressive riffs, leering vocals, and X-rated lyrics.

The record’s title had been inspired by Beany and Cecil, a cartoon Angus Young enjoyed as a child.

“There’s a character in it called Dishonest John,” Angus Young told Guitar World in 2009. “He used to carry this card with ‘Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap—Special Rates, Holidays’ written on it. I stored up a lot of these things in my brain. I picked out the things I liked best.”

Despite the record being released in September of 1976 and proving to be a major success in Australia, it wouldn’t be released in the US market until 1981—a full five years later—as the label believed it wasn’t of high enough quality (though a separate international release was issued in 1976, too). But after the band’s breakthrough album Back in Black saw major success overseas, Atlantic Records finally relented and Dirty Deeds became an instant smash hit in the US.

Speaking of the controversy surrounding the album, its saucy song titles and lyrical content, Bon Scott had said in a decades-old interview with Classic Rock 115: “Rugby clubs have been doing the same thing for years,” he explained. “Songs like that. The songs that won the Second World War were like that, with the chaps singing them as they marched into battle.”

Angus Young added: “There’s not much seriousness in it. It’s just rock’n’roll. Chew it up and spit it out. If you look at it this way, most of the kids in the street talk like that. It’s the language of the clubs that we heard when we started off in Australia; same when we came here, in places like the Marquee.

“Kids would be swearin’ their heads off. They don’t say, ‘Turn it up…’; they say, ‘FUCKING TURN IT UP!’ We’re as subtle as what they are. As far as radio stations go, you can turn on the radio and you wouldn’t like to hear your songs on the radio anyhow, cos it’s in there with Barry White playing his Love Unlimited bollocks. That’s a bit degradin’ for us.”

The album’s title track itself also faced a bizarre controversy upon its release—though it wasn’t for the usual shenanigans you’d expect from the cheeky rockers.

The song featured the lyrics “Just ring: 3-6-2-4-3-6,” which served as both a telephone number and the measurements of a shapely woman.

It turns out, the number was legitimate—it belonged to Norman and Marilyn White, a couple from Libertyville, Illinois, who later filed a $250,000 lawsuit after they were bombarded with calls thanks to the song.

With some fans interpreting the “hey!” as “eight”, several people dialled 3-6-2-4-3-6-8, with the couple claiming they received endless “lewd, suggestive, and threatening” calls, presumably requesting some dirty deeds at a cheap price.

Jimmy Barnes, 'For the Working Class Man'

Of all the solo and group albums released by Barnsey, perhaps none are as influential as For the Working Class Man, which was instrumental in painting the cultural picture of the blue-collared, hardworking Australian.

Most notably, its title track served as an unapologetic anthem for the self-sacrificing “working-class man” of the Eighties.

Barnes had said of the legendary track, “I went to America just after Bodyswerve and met Jonathan Cain, who was in The Babys and Journey. It means a lot to me. Most people thought it was written about me, but it was actually written about my audience—staunch, honest people, who work and who care.”

“It sort of touched a nerve with the Australian public, the song was written about people who go to see rock’n’roll gigs in Australia,” he said in another interview. “They save their money and they go out on the weekend and have a good time to forget their troubles.”

But behind the gravelly-voiced and wildly successful anthems from the album that resonated unreservedly with young Australians, Barnsey was viciously battling his own troubles at the time, an unwelcome and lingering side effect of childhood trauma.

“For 40 years, in front of the public, I was drinking myself to death,” Barnes told The Guardian in 2017. “If you did that in any other job, people would say, ‘You’ve got problems, mate’. But people didn’t see it like that because they were living vicariously through me.”

While he’s undoubtedly still the happy-go-lucky bloke we knew from his For the Working Class Man era, Barnes has shifted from vodka-swilling rock’n’roll star to devoted family man who credits his decision to go to therapy for being able to adequately deal with the painful memories of his childhood that he left dormant for so long.

“I had to really look at all the stuff that I’d had hidden, all the abuse and trauma. I had to look at that for myself, otherwise, it was going to kill me,” he said. “In the process of doing that, I got quite a bit of therapy, and I believe that opening up made me become a better person.”

Even so, Barnsey warned that the demons from all those years ago still linger, rearing their ugly heads every now and then.

“Sometimes I’ll be watching a movie, then I’ll see something in the movie that reminds me of something bad about myself.

“And I’ll start doubting myself and be unable to sleep, and I’m looking at the clock and it’s three in the morning and I’m thinking, ‘Am I good enough for the family? Am I a good enough person? Do I deserve this?’”

“But then I tell myself, I’ve been through all this, I’ll work through this, you can deal with this. And everything’s gonna be okay,” he said.

“The thing about the demons is, you never really get rid of them. They just hide, just waiting to pounce. You’ve got to keep on top and keep working on yourself.”

Divinyls, 'What A Life!'

Chrissy Amphlett appeared to emerge fully formed as Australian rock’s most striking frontwoman. Already boasting her signature shaggy fringe and mocking pout by the time of Divinyls’ 1981 debut single “Boys in Town”, she drew from her own teenage experience of fleeing Geelong to deliver a savage takedown of immature suitors and provincial limitations.

Featured in a film adaptation of Helen Garner’s Monkey Grip that also included Amphlett in an acting role, the song remains an urgent force, both in recorded form and in concert videos. Emboldened by the curt, slashing guitar of Mark McEntee and a rhythm section that would change often over the years, Amphlett populated her scathing tales of youthful disillusionment with a vivid vocabulary of howls and snarls that never seemed entirely at odds with her tuneful charisma.

After Divinyls had honed their spiky attack on 1983’s Desperate—with Amphlett poised as a successor to Debbie Harry now that Blondie were through—she and McEntee allowed some polish to gild their raw edges on What A Life!. But the intensity remains: while opener “Pleasure and Pain” was penned by partial album producer Mike Chapman and rocker-turned-songwriter Holly Knight, Amphlett pours herself right into the raging lyrics, addressed to a physically abusive lover. “Please don’t ask me how I’ve been gettin’ on,” she claps back, employing expressive vocal tics to vent her betrayal.

Amphlett’s clawing voice remains the focus across the album, though McEntee’s relentless amphetamine hits of guitar run a close second. “Motion” plays like a compact microcosm of a full live show, with Amphlett cool and controlled at the start, laughing and quivering during the bridge and absolutely raw-throated for the unhinged ending. That’s fitting for a song about her tossing and turning out of preoccupation with false friends and romantic restlessness, while her delivery turns downright jagged on the threatening “Guillotine Day” (“Your time is up”). Another anthem about leaving school young, “In My Life” exaggerates her grotty accent during a snide spoken-word section that single-handedly predicts Amyl and The Sniffers.

What A Life! captures Divinyls in mid-transition between the pub scene and the pop charts, all while Amphlett brandishes her proud sexual agency on tracks like “Casual Encounter”. Those tandem developments would soon collide to spark the band’s biggest overseas hit (and only Australian number one) in 1990’s “I Touch Myself”, an oft-covered ode to self-pleasure that was laughably controversial at the time. Directed by a pre-Hollywood Michael Bay, the video of course sees Amphlett stalk about with supreme confidence.

The combustible working relationship between Amphlett and McEntee would put an end to Divinyls by the mid-Nineties, apart from some fleeting reunion touring. When Amphlett died in 2013 after years of facing down breast cancer and other dire health issues, the loss was all the more pronounced because of just how much personality she had invested into her work. Singing openly about female desire in so many of her songs, Amphlett left generations of accumulated shame in the rear-view—where they belong.

Hoodoo Gurus, 'Mars Needs Guitars!'

How do you follow up a debut as explosive as 1984’s Stoneage Romeos? That sustained blast of garish juvenilia didn’t just announce Hoodoo Gurus as some of the Eighties’ most devoted worshippers of Sixties garage rock and lowbrow pop culture, but also scored a surprise perch atop the US college rock charts. That’s remarkable for a young Australian band who heralded their songs with ghostly mariners, stop-motion toy dinosaurs, and Three Stooges references.

Rather than double-down on the first album’s cheap thrills, though, singer/guitarist Dave Faulkner began working toward more personal songwriting without sacrificing the band’s larger-than-life retro fixations. Witness the long hair, paisley patterns, and western shirts showcased in the videos for their second album, or how the title still chews firmly on B-movie scenery. And in new drummer Mark Kingsmill—older brother to triple j honcho Richard Kingsmill—the rising Sydney quartet lucked upon a blurted, more immediate presence than departed stickman James Baker (an underground legend in his own right) for Mars Needs Guitars!.

But there’s no denying the newfound emotional depth of “Bittersweet”, which takes the lovestruck vibrancy and ringing jangle of Stoneage Romeos’ “I Want You” to a sadder, subtler realm—and gives it top billing as the album’s opener and lead single. Not to be outdone, “Death Defying” contrasts its quaint vocal harmonies and glistening country licks with lyrics that no longer sound remotely like wisecracks: “All my friends are dead or they’re dying / And our laughter turns into crying.”

Still, this is the Hoodoos we’re talking about, which means there’s still ample room to entertain impulses both left-field and self-aware: “Hayride to Hell” could be the calling card of a singing cowboy raised on The Gun Club and The Cramps, while “Like Wow—Wipeout” is equal parts satire and salute aimed at the band’s throwback influences. Faulkner overlays old-school American surf and rockabilly motifs onto Western Australia’s even vaster landscape on “In the Wild”, while guitarist Brad Shepherd sings lead on the title track’s chest-beating (and of course tongue-in-cheek) anthem of “primitive” pride. And on the reverb-streaked “She”, Faulkner somehow draws Banshees-worthy goth romance from his favourite selection of pulp clichés: observe the narrator’s dazed obsession with the South Pacific princess of a volcano-laden secret kingdom, making it a spiritual sequel to the first album’s two-part “Leilani”.

Catching these sonic and thematic easter eggs is akin to slowly connecting the dots between a box of horizon-expanding records gifted from an older sibling. That’s part of what makes Mars Needs Guitars! every bit as appealing as the subversive nostalgia and the muscled radio slickness (cue “What’s My Scene”) that bookend this era of the Hoodoos.

Beyond excavating the ripe fossil record of the Fifties and Sixties for unknowing young listeners at the time, it laid its own robust groundwork for the following decade’s alt-rock boom: the lopsided bass-and-drums opening of “Poison Pen” would be strongly echoed in Green Day’s 1992 breakthrough “Longview”, before Hole closed out the millennium by covering “Bittersweet” at the Big Day Out.

Grinspoon, 'New Detention'

By the end of the Nineties, Grinspoon had managed to—in just the space of two albums—go from relative unknowns winning triple j’s Unearthed competition to becoming household names, renowned for their unrelenting energy and ubiquitous nature.

However, even after just a few years as in-demand artists, Grinspoon were in need of some downtime. Taking things slower in the wake of their second album, 1999’s Easy, the group approached sessions for their third time with a bit more casualness, with a total of 45 songs emerging before they hit the studio. “It took a long time to write that record,” frontman Phil Jamieson would tell Double J in 2017, “but I think we needed to take a breath and just work out what we were gonna do.”

The result was New Detention, an album which was far more considered and polished than their previous efforts, but by no means an attempt to cut ties with their earlier years. With symphonic ballad “Chemical Heart” arriving as the lead single, it was clear there had been a shift within the Grinspoon camp, but one that ultimately worked.

Despite apprehension to showcase their third album with such a stylistic change, “Chemical Heart” would kick off a run of four singles taken from the record—including “Lost Control”, “No Reason”, and “1000 Miles”—and would result in the record hitting number two on the charts and ultimately going Platinum.

Speaking of the album almost 20 years on, guitarist Pat Davern told Rolling Stone Australia in 2021 that it was the start of a three-album streak in which “the band hit their stride”. New Detention was the record that proved to the world that Grinspoon weren’t just the young, rowdy stalwarts of the scene; determined to make loud music forevermore.

Rather, it showed they had the energy, the power, and the determination to flex their musical muscles and allow critics to take them seriously. It wasn’t the band turning their back on their roots and stripping their sound of the crushing downtuned riffs and powerful choruses they had become known for, it was expanding upon this sound and proving they were capable of writing some of the best songs of their career.

For many, New Detention marked the beginning of a new era of the Grinspoon story, and revitalised the band. It kicked off one of their most popular periods to date and allowed them to prove they weren’t just here for a good time, they were going to be here for a long time.

“It definitely put our Grinspoon lives on a different trajectory than what was going on,” Jamieson would later explain to Double J. It’s difficult to say just what Grinspoon’s legacy and influence would be like had New Detention never been written, but it’s fair to say that it was arguably one of the most important records they had ever made.

Something for Kate, 'Echolalia'

Ever since they first formed back in the mid-Nineties as Fish of The Day, Something for Kate have known they should never take anything for granted. In fact, many music lovers—frontman Paul Dempsey included—can remember that era when nascent alt-rock bands would form, record an album, and then fall victim to the dreaded call from the label telling them they were dropped.

Needless to say, when Something for Kate released their 1997 debut Elsewhere for 8 Minutes, it might have felt like their days were numbered. When 1999’s Beautiful Sharks followed, a sense of cautious optimism might have formed. But when they got the chance to make a third album, their upward trajectory left them feeling positive about what was to come.

Unfortunately, third album Echolalia was not an easy one to make. After years spent practically living together as a band, the trio found themselves in need of a break. Meanwhile, Dempsey had been experiencing a crippling bout of writer’s block. To combat these stressors, a trip to Thailand was undertaken, and as the story goes, Dempsey managed to pen lead single “Monsters” in about 20 minutes.

“We’ve always been really hard on ourselves in terms of what we want,” Dempsey told Rolling Stone Australia in 2021. “We have a bar that we’ve set for ourselves, and we have high expectations for ourselves.” These high standards seemed to eventually work in the band’s favour though, and armed with “the best batch of songs that we had come up with thus far”, they hit the studio with producer Trina Shoemaker to craft what would become—to many—their magnum opus.

Echolalia is an album that’s occasionally difficult to categorise. Some might label it as indie or alt-rock, and while that’s fitting at times, Echolalia is first and foremost a cinematic release. The textured instrumentation that accompanies Dempsey’s intricate songwriting is something to behold, with the record possessing an innate ability to awaken emotions that have long lay dormant inside of you, awaiting a record such as this to rouse them from their stasis.

Though singles such as “Monsters”, “Three Dimensions”, and “Say Something” would help propel Echolalia to a silver-medal spot on the charts, it’s hard to look past the aching brilliance of “Old Pictures”, the raw emotion of “You Only Hide”, or the almost dizzying characteristics of “Manmade Horse” or “Seasick”.

While diehard fans might claim the record could have been made better with the inclusion of beloved “Monsters” B-side “Hawaiian Robots”, Echolalia stands tall as a landmark release of the early Noughties. Even though Dempsey would state the group “never made it easy for [themselves]”, even he’s able to look back on the record with a sense of well-deserved pride.

“I just thought, ‘We’ve done what we set out to do; make a record we’re really proud of,’” he told Rolling Stone Australia. “I think it’s a really good record, and I’m really happy with everything we put into it, we got everything we wanted from it, and I’m really happy we met our expectations.”

The John Butler Trio, 'Grand National'

In 1996 John Butler was busking on the streets of Fremantle, Western Australia. A decade later he’d achieved an Australian number one album (2004’s Sunrise Over Sea) and an ARIA Award for Best Male Artist, and it was with these achievements that he entered the studio to record his fourth album, Grand National.

With his trio now rounded out by bassist Shannon Birchall and drummer Michael Barker, Butler was joined by Mario Caldato Jr (Beastie Boys, Jack Johnson, G Love) as co-producer and set about recording a new set of songs that continued his mindset to write from more of a personal and emotional base, rather than the issue-driven material he had hitherto become most well-known for.

Opening the album with “Better Than”, the die was cast for an album of up-tempo, groove-based celebrations none more so than “Daniella” dedicated to Butler’s wife Danielle Caruana, aka singer-songwriter, Mama Kin. What begins as a simple harmonica part over a shuffling beat opens up to become an all-in love-fest as Butler proposes, “Daniella won’t you be my Cinderella?” before a deliciously-electric guitar solo takes the love-letter to joyous new heights before settling down as intimately as it began.

Songs such as “Funky Tonight” and “Gov Did Nothin’” (featuring Vika and Linda Bull) continue the propensity for rave-ups. The former speaking of romance over an infectious groove that shoots for the stars (think the end-section of the Stones’ “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking?”), the latter, a number of eminently more serious intent. It builds from a swampy lament to an all-out jam that with a full horn section, a Wurlitzer organ and more, takes the adventure to all corners of the bayou over an impressive eight minutes. Quieter moments, such as the ever so slight symphonic “Caroline” and the gentle romantic reggae of “Groovin’ Slowly” balance things out across 13 tracks.

Named Grand National after the resonator guitar played by Butler, he also commands numerous stringed instruments throughout the album, a variety of acoustic and electric guitars, banjos, ukuleles and lapsteels, as well as harmonica, mouth harp and didgeridoo—so one certainly can’t say he didn’t bring his work to the office.

All this effort certainly paid off, with the album going multi-Platinum and adding to Butler’s popularity in the US and Europe. For a roots-based singer-songwriter with a seemingly endless amount of grooves at his fingertips, Butler by now was opening up his heart all over his work, as well as moving into the realms of his much-loved soul music and alt-rock.

By the time his fifth album, April Rising, was released in 2010, Butler had again changed his trio to incorporate brother-in-law Nicky Bomba (Bomba, Melbourne Ska Orchestra) on drums and Byron Luiters (Ray Mann Three, Brown Sugar) on bass. In the decade since, he’s continued to change band members, recruiting what he considers as the best personnel for the songs he’s written in the era that he’s in. It’s been an entrancing musical journey as a result.

Killing Heidi, 'Reflector'

It’s been more than two decades since a scrappy pop rock band from Violet Town in regional Victoria released their debut album. Written between 1997 and 1999, the songwriting storm of siblings Ella and Jesse Hooper captured the existential shuffle between teenage self-assuredness and crippling vulnerability. In the lead-up to the record’s release, multiple signifiers showed they were playing to win.

Having already won over angsty Australian youths with triple j Unearthed favourite “Kettle”, many expected the record’s first single “Weir” to piggyback its predecessor and jump to new heights. It didn’t; at first.

“It was very polished rock-pop, and so people didn't quite know where to play it,” frontwoman Ella Hooper told Double J about the lack of radio support. Six months later though, the track jumped to number five on the ARIA chart and Killing Heidi became a household name. Second single “Mascara” then went to number one, soundtracking every young person’s generational disdain along the way.

Unleashed in the first autumn of the new millennium, Reflector was made for misfits and the uninvited. The record careens from polished pop (“Mascara”), bleak noise rock (“Real People”) and punk boogie (“Live Without It”) and marks a definitive songwriting statement about isolation and individuality. “Class Celebrities”, a vignette of high school hierarchy, bolts with urgent rock precision. Meanwhile tracks like “Leave Me Alone” and “You Don’t Know” are flecked with crunchy White Zombie and Sepultura references.

Recorded in halves at Sing Sing in 1997, and Harris Road in 1998, the studio experience marked the band’s first time coming face-to-face with the music industry. As they took the train from their country town to the Big Smoke of Melbourne every weekend to record, they felt intimidated by the sophisticated gear around them and Paul Kosky’s “production with purpose” direction. You can hear that intimidation turn to frustration on “Weir”. When Ella was asked to make the chorus sound bigger; she ended up screaming it.

Killing Heidi were an unlikely success story, a small town band with big things to say. But as they travelled the world in support of the album, between American cities, packed venues, and pokey hotel rooms, the weight of a gruelling tour and press schedule—and an expectation to be the big sister to young fans her own age—took its toll on Ella Hooper. “There were definitely nights where I couldn't handle it,” she told Double J. “I would have maybe burst into tears or cried myself to sleep. It's a very full on experience for a young person to have.”

The same year of the record’s release Killing Heidi were booked on the now-defunct festival juggernaut Big Day Out in Sydney and Melbourne. By the time the festival dates rolled around, Killing Heidi had outgrown the side stage status they were assigned. The Melbourne show was especially raucous; despite security turning people away, the crowd drowned the stage amps with screams, climbed the stage scaffolding, and broke two water pipes.

Reflector went on to become one of the fastest-selling albums in Australian music history and created the reigning model for many local pop-rock crossover acts to come.

Powderfinger, 'Vulture Street'

Powderfinger had the type of career most artists can only dream of. University friends, they found their sound on album two, embarked on a run of five successive number ones, then disbanded while on top, with a final, goodbye national tour to over 200,000 fans.

The Brisbane rockers, unlike many of their contemporaries, didn’t relocate to London or LA to pursue the dream. They stayed in their hometown and, for a time, were the most successful band in the country.

Like The Go-Betweens did with Spring Hill Fair, an album considered one of their finest works, Powderfinger infused part of their hometown on Vulture Street, and in the form of its final single “Since You’ve Been Gone”, some tragedy close to home.

Powderfinger’s fifth studio album is the sound of a band in the finest of form, and it takes its name from a main road that runs past the Gabba, the main stadium for the Brisbane 2032 Olympic Games.

Anyone who has watched a cricket match at the Gabba will be familiar with the Vulture Street End. Powderfinger bowled some rippers on this LP, which, like the band’s previous two efforts, was produced by Nick DiDia, and was mixed by Brendan O’Brien, both legends of the studio world.

Opening track “Rockin’ Rocks” does what it says on the box, and announces the intention of this album. The first single, “(Baby I’ve Got You) On My Mind”, is all-beef, snare fills, and guitar licks. “Sunsets”, the third single, is a standout and one of the band’s finest.

“The songs are usually left up to the imagination, especially on this album,” Darren Middleton told this reporter in 2004. “We don’t sit around imagining where to put the string section, there’s none of that stuff. What we can do in the band room, we can do live, and that’s pretty much what you hear on this album. There’s not too much in the way of trickery.”

On the bluesy “Since You’ve Been Gone”, frontman Bernard Fanning addresses his elder brother, John, who was sick during the writing of Vulture Street, and was unable to overcome his illness. Fanning recounted the recording sessions in a 2017 interview with the ABC. “You have feelings of guilt,” he said. “Since You’ve Been Gone” is a bluesy shout-out to his bro, made with a warm heart. On it, he sings, “I just want to say that I miss you and I’ve felt pitiful since you’ve been gone”.

What was missing in the career of Powderfinger was the big international hit, though “My Happiness” from 2000’s Odyssey Number Five came close. Were it not for Chris Martin falling ill and cancelling Coldplay’s US tour in the early Noughties, for which Powderfinger were the opening act, who knows what might have transpired.

Vulture Street had its own life outside of Australia. The band, signed to Universal Music, took a different route into the UK with Richard Branson’s V2 label, which handled the release there for the first time. “We didn’t feel that [Universal] were going to be particularly motivated to get going on this album again,” Fanning told this reporter during an interview in London in 2004, while on tour. “We definitely had the live market in mind,” he added. “With this record in particular, it was very much a case of how can the five of us make this song sound good and be able to perform it live.”

Radio Birdman, 'Radios Appear'

For the completionists out there, it’s hard to find a “definitive” version of Radio Birdman’s 1977 debut, Radios Appear. Diehards will argue that the original Australian edition—which opens with a cover of The Stooges’ “TV Eye” and features black artwork—is the way to go, while others will argue the 1978 white-covered “Overseas Version”—which added the then-nascent single “Aloha Steve & Danno”—is superior. Others still will cite the expanded version from the Nineties as the most complete package of the record, given that it serves as a “best of both worlds” situation in regards to its tracklist. Casual fans likely won’t care about any of this, just as long as it’s Radio Birdman pumping out of their stereo.

Radios Appear arrived just a few short years into Radio Birdman’s career, which had begun in 1974 after American guitarist Deniz Tek teamed up with Rob Younger to create what would later be called one of the world’s first punk bands. Inspired by the likes of Blue Öyster Cult (whose “Dominance and Submission” would give rise to the album’s title), and armed with the Motor City sound of artists such as MC5 and Iggy Pop from Tek’s hometown of Detroit, Radio Birdman were raw, hard, and fast, with their high energy at odds with the sound and style of the Australian music scene at the time.

Despite a lack of mainstream acceptance, Radio Birdman forged onwards, performing frequently while honing their unapologetic sound. Issuing debut EP Burn My Eye in 1976, the group followed things up with Radios Appear on the independent Trafalgar label the following year. Like everything they had done up to this point, the record was rough and raw, yet maintained a powerful approach to songwriting which focused heavily on melody and message.

The bouncy garage-rock of tracks like “Do the Pop” showed heavy Sixties influences, while standout “New Race” seemed to serve as the blueprint of future punk anthems to come. But it wasn’t all raucous intensity, with the cryptic “Man With Golden Helmet” offering up psychedelic piano passages, while later single “Aloha Steve & Danno” would serve as one of the group’s best-known compositions thanks to its iconic surf-rock homage to Hawaii Five-O.

While The Saints had issued (I’m) Stranded just five months prior, Radios Appear felt to many like the beginning of what would become punk music; a blueprint of high energy catharsis recorded on analogue equipment. It was raw, it was powerful, and it spoke to the masses.

Sadly, Radios Appear would ultimately be the last that many would hear of Radio Birdman for close to two decades, with a lengthy breakup taking place following the recording of their Living Eyes album in 1978. Perhaps this time away helped to grow the legend of who Radio Birdman were, and what could have been, but one thing remained undeniable fact, Radios Appear was a stone cold classic, no matter who you were.

The Church, 'Starfish'

While their music conveyed an ethereal otherworldliness, The Church were always a rocky proposition beset by all-too-human dramas. It’s probably what has made the ride so enticing.

Having released the excellent Heyday album in 1985, the band’s international profile was on the rise, even if in Australia it had somewhat obtusely fallen. Even so, it was on a European tour in support of the album that saw guitarist Marty Willson-Piper quit the band. It’s said that after assurances from primary singer/songwriter, Steve Kilbey, that subsequent works would be more collaborative if he returned. And so, with their stocks in ascendancy in the US, the band signed a new record deal with Arista and decamped to Los Angeles to record what became Starfish.

If there was a hint of promise in the air, it was offset by Kilbey’s distaste for the LA landscape and the fact that co-producers Waddy Wachtel and Greg Ladanyi wanted things done the American way, which was unsurprisingly a stricter regime than Kilbey (who was required to undertake singing lessons), Willson-Piper, guitarist Tim Powles, and drummer Richard Ploog were previously used to. Although not to the band’s initial liking—they had reportedly wanted a sound closer to a live gig and felt that the mix sounded empty—Starfish propelled The Church as far into the stratosphere as they would ever get. This was mainly down to dreamy surreal “Under the Milky Way”, which became an almost immediate international hit, even if Kilbey insisted that he and his partner Kaarin Jansson had written it by accident and that the song didn’t appeal to him at all (in recent years he’s been far kinder to it). While not as big a hit, “Reptile” proved to also be an attention-grabbing single, with its cool delivery complemented by its mesh of atmospheric guitar riffs and structural dynamics. Other songs such as “Destination”, “Lost” and “North, South, East and West” served to evoke the dislocation Kilbey and co. felt with the LA environment, both in the studio and on the street. Either way, Starfish came in at number 32 on US Rolling Stone’s 1988 Album of The Year poll and cemented The Church as an international act, even if the follow-up, 1992’s Priest = Aura (which teamed the band reluctantly once more with Wachtel) and their Nineties output, never saw them reach the same dizzying—yet troubling—heights. To Kilbey’s amusement “Under the Milky Way” has been adopted as something of a beloved Australian anthem. It also, as it turns out, wasn’t the only time Willson-Piper would quit The Church—his shoes have been filled since 2014 by former Powderfinger guitarist, Ian Haug. The band remain as enigmatic—and ethereal—as ever.

Jimmy Barnes, 'Soul Deep'

Mushroom Records founder Michael Gudinski famously expressed his sorrow that he never signed pub-rock icons Cold Chisel to his equally-iconic record label when he had the chance. In the mid-Eighties though, Gudinski was given the chance to correct the mistakes of his past when he signed frontman Jimmy Barnes to Mushroom, kicking off a professional relationship with “the finest Australian singer [he’d] ever heard”; Barnes’ first six records all hit number one on the ARIA charts.

But his fifth studio album was one which, on paper, might have seemed a little bit strange for fans of the artist. While records such as Bodyswerve and For the Working Class Man were undeniable entries into the rock genre, 1991’s Soul Deep saw Barnes taking a different path and unveiling an album of soul and R&B classics. Of course, it made sense, really. Barnes’ voice almost seemed custom-built for a genre in which the most important quality to bring to the performance is passion, and longtime fans of the artist wouldn’t have been surprised at such a stylistic shift, with soul classics having been an integral part of Barnes’ own musical upbringing and evolution. “Some of these songs I used to do in Chisel,” he told MTV ahead of the album’s release. “They’re the songs that influenced me the most.”

Working with producer Don Gehman, Barnes recorded the album in just ten days, with the 12-track record featuring classic numbers originally made famous by the likes of Sam Cooke, Stevie Wonder, The Supremes, Joe Tex, Al Green, and Jimmy Cliff. “It’s like going back to school and touching base with the singers I was listening to,” he would explain in 2016.

Soul Deep would also go on to spawn three singles, including “I Gotcha”, “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”, and “When Something is Wrong with My Baby”, which would see Barnes team up with fellow icon John Farnham for one of his most successful duets to date.

However, while the prospect of a Jimmy Barnes album being a successful one almost seemed like a sure-thing back in the early Nineties, no one could have foreseen just how big the record would be. Not only did it peak atop the charts, but it would eventually go 10x Platinum, winning two of its six ARIA Award nominations. By the end of the decade, it was the biggest-selling album on Mushroom’s roster. (Notably, the rest of the top five were also Barnsey records, in case you were wondering.)

The success of the record not only cemented Barnes’ status as an inimitable performer, but as one whose abilities weren’t simply limited to one genre. A veritable musical chameleon by this point, he would also revisit the concept on three more occasions, including 2000’s Soul Deeper, 2009’s The Rhythm and The Blues, and 2016’s Soul Searchin’, with all but the former peaking atop the charts.

Ultimately though, Soul Deep was a revelatory addition to one of the country’s most vital discographies. It proved that Barnes was set to forever be a staple of Australian music, with his legendary voice set to ring out for eternity, whether it was singing rock music or soul classics.

Gotye, 'Like Drawing Blood'

De Backer, Wally, Walter, Wouter, Gaultier, Gotye; it doesn’t matter what you call the beloved Belgian-born, Aussie-grown musician, what matters is how the multi-instrumentalist crafts such a diverse collection of sounds like no other. Like Drawing Blood, Gotye’s 2006 sophomore album, is testament to his expansive nature of musicianship. Drawing on vast influences like Eighties pop, jazz, reggae, funk, motown, indie-rock, experimental electronica, and even tango, the 11 unique tracks are skilfully moulded together to provide a musical experience unlike any other.

Preceding his 2011 hit track “Somebody That I Used To Know”, which saw the singer-songwriter-producer propelled to heights of global success, Like Drawing Blood acted as the stepping stone to reach such elevation. This second solo album earned Gotye the Most Outstanding New Independent Artist Award at the AIR Awards, the top spot on the triple j listener-voted Best Album Of The Year, and 2007’s ARIA Award for Best Male Artist. But it wasn’t all glitz and glamour in the beginnings of Like Drawing Blood. Chopped, changed, and recrafted samples collected from bargain-bin vinyl make up the majority of sounds on the album. After being gifted a 400-strong record collection from a recently deceased neighbour’s husband, from there the album blossomed. The sample-heavy record went on to be assembled and recorded within his bedrooms in Melbourne, as he moved to several new homes across the city over a two year stint. The constant shifting and ensuing difficulty faced while recording across multiple environments is what inspired the album’s title.

Complementing the sample-based eclectic display of musical intelligence, is Gotye’s stunning vocals. The genre-defying tracks are brought to life by vocal abilities that stretch from mesmerising in experimental-funk album opener “The Only Way”, to droopy and attention-demanding in melancholic “Hearts a Mess”, to laid-back and smooth in the theatrical, tangoing number “Coming Back”, to charming and layered self-harmonisation in motown-inflected, catchy crowd-favourite “Learnalilgivinanlovin”. Gotye may know his way around a multitude of genres, instruments, sampling loops, and self-production, but his malleable vocal talent is yet another factor that sets this accomplished musician apart.

Each song on Like Drawing Blood takes you on a well thought out ride, igniting profoundly specific feelings. The slow moving instrumental “Seven Hours With a Backseat Driver” certainly feels like such a journey. “Hearts A Mess” sounds exactly like a messy heart would, and the dark, animated, Tim Burton-esque music video is synonymous with the sound too. “A Distinctive Sound” certainly has just that—with a collection of sampled TV and radio voices from times past, where we first hear a more grunge styling on the album. “Thanks for Your Time” takes us through the all too familiar experience of being on the phone with a friendly but overwhelmingly unhelpful call centre operator. “Night Drive” is a lighthearted, soothing break, reminiscent of—you guessed it—a pleasant night drive.

Captivating from start to finish with no two songs alike, Like Drawing Blood showcases Gotye’s unique and eclectic talent, marking his entrance to the world stage.

Hilltop Hoods, 'The Hard Road'

When it comes to the history of Australian hip-hop, the Hilltop Hoods’ influence and impact is absolutely undeniable. There is a reason why the Adelaide trio has endured for over 20 years; their catalogue has evolved with them as humans. Proving there was room for rap music within the commercially successful pop world, the Hoods are trailblazers of a uniquely Australian sound that dictated the genre through its early formative periods.

In 2006, their fourth album dropped: The Hard Road. Following on from the success of The Calling—an album that brought the public the cultural hip-hop moment that was “The Nosebleed Section”—The Hard Road achieved notoriety all of its own.

Claiming their first ARIA number one spot with the record, The Hard Road in some ways set the Hoods on the trajectory to the widespread success they still enjoy today. The album is home to some classics including the title track, “Clown Prince“, and “Recapturing the Vibe“, though to dig a bit deeper, there’s greater appreciation to be gained from songs like “Circuit Breaker“ and “Breathe“ with time on your side.

By this point in their careers, the partnership between Suffa and Pressure is well locked in. The contrast of the two MCs’ voices is one of the Hoods’ enduring draw cards and on The Hard Road, both rappers are at a particular creative peak. DJ Debris’ production leans comfortably into addictive beat patterns and melodies, backing the confident flows of Suffa and Pressure in a way that never feels out of pocket.

And speaking of production and arrangement, the success of The Hard Road in its Restrung form (released the following year) further proves how much of a classic the original is. The Hard Road incorporates different elements and inspirations; across it you can pick up on funk, jazz-leaning keys, and pop, expertly mixed together with the boldness of Debris’ rap production.

What was supposed to be a one-off concert performance with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, led to an official release of The Hard Road Restrung—a format the Hoods would revisit to similar levels of success later in their career.

Like a lot of the Hoods’ music, The Hard Road is one of those albums that would be equally at home in a stadium as it would be bumping in the car any night of the week. That’s the appeal of an act like the Hilltop Hoods in a nutshell. Their accessibility as artists and performers has elevated them to successes not many other Australian artists could achieve and at the same time, they’re still the same guys you could see with their families in a smaller town like Adelaide.

The Hard Road—in an eight-album strong catalogue—still sits as a solid fan favourite today. The albums that followed would see the Hoods grow even further in their ambition and artistic boldness, yet there is something special about how The Hard Road harnesses the cheek, confidence, and well-developed skills of the trio that none of their other albums can touch.

Silverchair, 'Freak Show'

While Australian music has seen its fair share of rags-to-riches stories, the rise of three Newcastle school students seemingly overnight into global rock heroes, right at the tail end of grunge, was unprecedented and has not had an equivalent since.

Singer/guitarist Daniel Johns, bassist Chris Joannou and drummer Ben Gillies began in 1994 as Innocent Criminals but quickly found fame as silverchair (don’t forget the little ‘s’ as true fans know all too well) upon the release of their debut album, the Kevin ‘Caveman’ Shirley-produced Frogstomp, in 1995.

Their straight up three-piece grunge music caught on quickly as the band toured Australia and the world, as they became bona fide celebrities at a time when most teenagers are doing everything they can to disguise their acne. During this time Johns was writing the band’s second album, Freak Show, clearly dealing with the ridiculous amounts of attention they were receiving, and the attendant backlash that comes with such extreme amounts of popularity.

The (near) title track “Freak” is an exercise in this: “Body and soul, I’m a freak / If only I could be as cool as you,” Johns opines, as the guitar crunches and Joannou and Gillies provide world-class rock solid rhythm to suit. It’s a lament again visited on tracks such as “Abuse Me”, “Pop Song for Us Rejects” and “Learn to Hate” with the band playing as angry as they may have at times been feeling inside—after all, success, as the Baby Animals once noted, is notorious for causing stress. Even so, with producer Nick Launay by their side, the “Nirvana in pyjamas” criticisms given to Frogstomp were soon to be laid to waste, as Freak Show hinted at the potential depth of Johns’ songwriting and what was to come. “Cemetery” hit upon symphonic realms that Johns would later revisit and develop. “Petrol & Chlorine” may sound as if it’s a grunge anthem if ever there was one, but it’s a restrained piece that is deeply reflective. “The Door”, meanwhile, hints at Eastern elements in the guitar riffery and offers up a more subtle hard rock approach to say, the likes of “Pure Massacre” or “Israel’s Son” from the debut LP.

Freak Show was launched with typical Murmur (read: Sony) aplomb at Sydney’s Luna Park, echoing the sideshow themes present in the songs and the LP cover. While it didn’t match the out-of-the-box success of its predecessor, Freak Show saw Silverchair maintain their international presence and paved the way for more adventurous songwriting from Daniel Johns from that point on, as the game often changed quite dramatically between 1999’s Neon Ballroom, 2002’s Diorama and the band’s last album, 2007’s Young Modern. He continues to baffle fans and critics alike to this day, but that’s certainly always made things interesting.

Kasey Chambers, 'Barricades & Brickwalls'

A daughter of musicians, it came as no surprise that Kasey Chambers would follow in her parent’s footsteps. Performing and releasing albums as a family, the Chambers’ Dead Ringer Band provided the platform that kicked off the career of one of Australia’s most renowned country artists.

The follow-up to her successful debut, 1999’s The Captain, her 2001 sophomore outing, Barricades & Brickwalls, put the country girl’s name in lights, thanks to the widely successful “Not Pretty Enough”. Ironically, a song about not fitting into the music industry was the breakthrough that saw the young artist do just that. Chambers’ sentiments in “Not Pretty Enough” connected to listeners on a new level, and for many would act as the ‘gateway drug’ to country music. Barricades & Brickwalls quite figuratively broke down barricades between the mainstream population and the not-so-commercially-popular genre.

Treating songwriting as a form of therapy, the album was written by Chambers herself, with aid from her father, Bill Chambers, and Worm Werchon. Produced by her brother Nash, her humble roots of family music-making were still strong. Exceeding expectations set by her first release, the album catapulted the singer-songwriter into heights of success no other Aussie musician had found before. Barricades & Brickwalls and its hit single would make Chambers the first Australian musician in history to have an album and single atop the charts at the same time. At the following ARIA Awards, the album would win Chambers the titles of Album of The Year, Best Female Artist, Best Country Album, and would be the highest-selling album by an Australian artist in 2002, alongside highest-selling single.

Created while pregnant with her first child, the 14 tracks on the album—including hidden album closer “Ignorance”—are deeply authentic. Revealing, personal lyrics allow Chambers’ vocals to lead, while the instrumentation takes a back seat. Moody themes of loneliness, restlessness, and isolation abounding, Chambers tugs firmly on heartstrings in tracks where she makes herself most vulnerable: “Million Tears”, “Nullarbor Song”, and “Falling Into You”, the latter providing a gentle moment of stillness in the otherwise rock-leaning, upbeat album.

On the other hand, despite what their names suggest, “On a Bad Day”—which features accompanying vocals from Lucinda Williams—provides the remedy for just that, the light fiddle sections complementing Chambers’ soothing voice, while “Little Bit Lonesome” leans into more vintage honky-tonk stylings, adding a twangy, jovial lift.

The eponymous track provides a heavier, rockier, side to Chambers than we had previously seen, while the collaboration with The Living End on “Crossfire” pushes the boundaries again, providing the album’s most rock-forward moment. Another notable collaboration comes by way of Australian music icon Paul Kelly, on the emotion-driven duet “I Still Pray”.

Ebbing and flowing between catchy, uptempo tracks which bridge the gap between country and pop music, and more bluesy, downtempo ballads, Barricades & Brickwalls showcases Chambers’ growth. From her Nullabor Plains origins to flashy red carpets, the album broke the mould of country music in Australia and ignited a new fanbase of country lovers.

The Triffids, 'Born Sandy Devotional'

The Triffids’ Born Sandy Devotional is an ode to the fractures in old Australia. Perth as a desolate and sweaty landscape becomes a caricature of itself. The mood is riddled with longing and lost love. The album unwinds as a sepia-tone trip through Perth in a boozy adolescent gaze that goes on to shape the memories of a generation.

It’s sparse, ethereal, and lonely. David McComb drives the quintessential road album. Where road movies are grounded in themes of masculinity, roaring engines, rebellion, and rediscovery; McComb howls: “I believed you would lead me through this life of crime / I believed you would lead me as the blind lead the blind.” At the crossroads of where he’s come from and where he’s going, there’s an open landscape that goes nowhere. Paul Kelly said of the album: “Innocence and crime, there’s a real loneliness there.” Innocence and crime are the ghosts Australia’s battler mythology is bred from. Born Sandy Devotional is a conscious relationship with, and reckoning of, that landscape. The treacherous interior landscape that colours the drunk, cavernous expanse of Western Australia. “The sky was big and empty / My chest filled to explode / I yelled my insides out at the sun / At the wide open road.” McComb dug deeper and exploited the burnt-out terrain of his Perth upbringing to tell the story of whatever was going on inside his head. A story of unrequited love, of youthful angst, and misguided intentions. Quiet moments are sonically treated with epic breadth. And then there’s the strange acapella interlude, “White Shawl”, in which McComb speaks: “She said ‘I’ve the soul of a flea’ / All fleas inhabited by the souls of drowning men / Hear their tiny cries / Blind to remorse / Insensitive to excess / And bound to repeat / They’ve fallen from grace / Again and again and again, so she said.”

The album was fronted by The Triffids’ poetic point man, McComb, who pieced together the story of Australian disillusionment with the help of Echo and The Bunnymen’s producer Gil Norton. The narrative was brought to life by “Evil” Graham Lee’s glowing pedal and lap steel guitar, Martyn Casey’s troublesome bass line, Jill Birt’s chromatic voice, the colonial echo of Robert McComb’s violin, and the posturing of Alysa McDonald’s drums. All recorded in a studio that usually recorded reggae and dub, lending to the drawn out sound of the record—a reflection of the psychological panorama McComb is coming to grips with. In 2006, Nick Cave wrote a blog about McComb’s music, Cave writes: “His own songs call from the strangest places and at the oddest hours. Whether calling from the baking salt pans of the West Australian desert or the darks of a broken heart, whether praying or pretending to pray, their gist is hopeful and brave.”

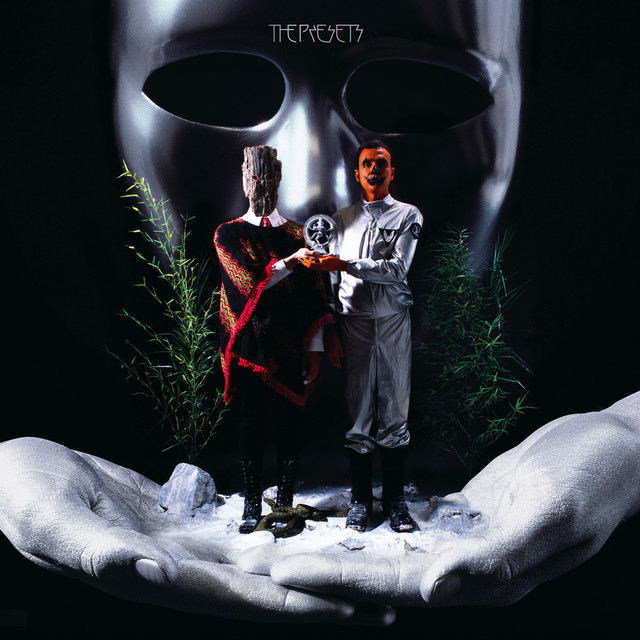

The Presets, 'Apocalypso'

There are few Australian dance records that capture the essence of the genre and live music culture as well as Apocalypso does. Following on from the success of The Presets’ debut album Beams, Julian Hamilton and Kim Moyes had no set formula when it came to producing its follow up.

Though Apocalypso would be released in 2008, production began in the preceding year, with the duo working on ideas in Byron Bay and on the road through Europe before eventually being recorded in their home studios and being sent between studios in Sydney, Los Angeles, and London for its final touches. Perhaps it’s this process that brings a definite international flair to Apocalypso in its final form.

The album perfectly captures the live energy of The Presets: the urgency and mammoth impact of “My People” is matched by the hypnotic and delightfully warped “Talk Like That” and “Kicking & Screaming”, for example. Apocalypso is Hamilton and Moyes positively thriving within each other’s company as performers, and knowing how to present a textured sonic journey in the space of fifty minutes.

It is an album that is effortlessly sleek, bangs in all the right places, and retains a sense of fantasy right throughout. The space for ruminating on songs like “If I Know You” and “Together”, matched by the loftiness of “This Boy’s in Love” showed The Presets’ knack for matching feelings of seduction and yearning with sonic eccentricity and even frustration.

It’s gorgeously warped as a record; buoyant horns and hectic synths, Hamilton’s vocals and Moyes’ percussion ensure Apocalypso existed in a lane all its own.

Apocalypso is the type of album that simply begs you to let loose, but at your own risk. For as soon as you invite in the throttling nature of “My People” and the ridiculously fun “Yippiyo-Ay”, it’s impossible to shake their effects off.

The album is a great marker for The Presets too, showing their full graduation from popular club act to a formidable headline force capable of holding it down in massive venues not just in Australia, but internationally too. The way Apocalypso bends and weaves, and is as happy to be flung from one extreme to another, perhaps set a new foundation for The Presets on ensuing records. Unafraid to slow things down and appreciate the space on a record, then following up with absolute club belters, it’s an album that properly kicked the door down and properly announced that yes, The Presets were here.

Apocalypso became a groundbreaking album for Australian dance music. Not only did it bring an act like The Presets to mainstream success, but its 2008 ARIA Album of the Year win properly put the genre on the map: it was the first dance record to take out the top gong. Artists like Cut Copy, Empire of The Sun, and more recently, Flume, would follow suit in providing cultural moments in a similar vein, but Apocalypso shifted the outsider perspective of what Australian dance music could be upon its release.

Cold Chisel, 'Circus Animals'

When the dust settled on 1980’s East, Cold Chisel were a band at the top of their game. Their third album, East had turned the Adelaide outfit into one of the country’s biggest rock acts, hitting number two on the local charts, breaking into the US charts, and eventually going five-times Platinum. But how do you follow up an album like that; one which has rightfully been called one of the country’s greatest records?

As frontman Jimmy Barnes would later explain in the book 100 Best Australian Albums, the group’s plan was to effectively rebel against what had made East so popular; defying the pop formula to try something completely new. “There was no way of improving what we’d done on East, so we had to think of new things to try,” he explained.

Working again with producer Mark Opitz, the group began work on an album tentatively titled Tunnel Cunts. Cold Chisel emerged from their sessions at the start of 1982 with the newly-rechristened Circus Animals, which subsequently became their first chart-topping record—a feat that would become commonplace for the group.

Upon its release, former Rolling Stone Australia Editor Toby Creswell called the album a “deeply flawed masterpiece, brilliant not so much in spite of the flaws but because of them,” later labelling it a “really extraordinary piece of work”. True, some of the more experimental arrangements may have divided fans to an extent, but at its core, Circus Animals was Cold Chisel unleashed; a band with nothing to prove, shooting for the moon just because they wouldn’t settle for anything but the best.

Kicking off the “You Got Nothing I Want” (itself inspired by The Rolling Stones’ “Start Me Up”), Circus Animals is in-your-face and unapologetic, yet not without sentiment. The classic pub-rock sound makes itself clear on tracks such as “Bow River”, “Houndog”, and closer “Letter to Alan”, yet drummer Steve Prestwich humanises the band more than ever with his beloved anthems “Forever Now” and “When the War Is Over”, highlighting Cold Chisel as masters of the energetic and reflective sides of the coin.

As Opitz would later note in his book, Sophisto-Punk, Barnes had come around to his way of thinking, which effectively amounted to; “Sure, let’s keep our integrity, but let’s have some fucking hits as well”. The hits were there, and the musical integrity was more than apparent, with cuts like “Taipan” and “Numbers Fall” showing off that sense of versatility that made Cold Chisel so mystifying.

Reflecting on the album for Sophisto-Punk, Barnes explained that its title related to Cold Chisel deciding that “being in a rock’n’roll band was like being in a circus”. The constant set-up/pack-up before moving to a new town to perform would take its toll on the band, but they ultimately embraced the concept, even putting on a show with an actual circus in Sydney with the band serving as the final act.

“The first night we had some animals involved; camels and things like that,” he explained. “But with all the people and the ruckus, the animals went nuts and ran through the crowd and nearly stomped people to death. So the next night there were no animals, it was just us—we were the animals.”

Eddy Current Suppression Ring, 'Primary Colours'

The lore of how Eddy Current Suppression Ring came to be doesn’t feel possible any more. It is hard to imagine something so organic, by chance, and fateful could be born in this age. The band’s fabled beginnings track back to 2003, following a Christmas Party at the Corduroy Records vinyl pressing plant where all four members worked.

As the night dwindled, drummer Danny Current (Daniel Young) and guitarist Eddy Current (Mikey Young) kicked off a well-oiled jam session, encouraging now-lead singer Brendan Suppression (Brendan Huntley) to ad-lib vocals into a tape recorder.

None of them had ever written a song or been in a band. After enlisting the ranks of bassist Rob Solid (Brad Barry), the tape recording from that kismet evening birthed the debut 7-inch from Eddy Current Suppression Ring, “Get Up Morning”.

In 2006, the band released their eponymous debut album through the now-defunct Australian punk label, Dropkick. Recorded in just four hours on an eight-track tape machine, with a budget of $250, the self-titled album is weirdo garage at its finest. Indebted in art school pop and buoyed by dopey, juvenile charm, (“I ate all my veggies and I ate all my soup, now can I have just one scoop,” sings Brendan Suppression on “Cold Ice Cream”), it became a favourite amongst live music fans.

One of the country’s best live acts, Suppression’s frenetic live performance earned them comparisons to the likes of Ian Curtis, The Stooges, and X. Brendan Suppression, armed with his trademark leather gloves, twitched and paced around the stage.

In 2008, they returned with Primary Colours, a slightly scrubbed-up annex of its predecessor. There was no gear-switching or grand reinvention, the bones of the music remained much the same. Primary Colours is slightly finer tuned, but never at the expense of Eddy Current Suppression Ring losing their spartan sweetness.

“This one was slightly more extravagant but not too extravagant,” Eddy Current told Australian Music. “I think rather than try to achieve some sort of sonic perfection, just trying to capture the four of us playing together is the most important thing.”

Eddy Current Suppression Ring are a level-headed band that never substitute their fascination with everyday life in favour of escapism. Primary Colours features some of the band’s best kitchen sink realism: “We’ll Be Turned On”, an equation of sexual congress with a checklist of menial chores, (“When I come home to you / Gonna do all the things I said I would do / Like I / Fix the antenna / You come on home and nothing could be better.”)

Primary Colours was received to widespread critical acclaim, peaking at number 13 on the ARIA Hitseekers Chart in June 2008. The record would go on to win the Australian Music Prize, and score an ARIA Award nomination for Best Rock Album. There hasn’t been anything like it since, but not for want of trying by anyone in the Australian music scene. Whether it be from its title, its artwork, or its musical approach, there’s a sense of purity in Primary Colours, and that’s the sort of thing that can’t easily be replicated.