Rolling Stone’s 200 Greatest Australian Albums of All Time

Rose Tattoo, 'Rose Tattoo'

Rose Tattoo embodies the Australian outlaw spirit, I know because I was a Harley-burning, whisky-guzzling, full-patch, one-percenter running my world into the ground with hard luck and close calls. “My life isn’t easy baby, it’s the life that I need / I got music livin’ inside of me, I gotta set it free”, spits Angry Anderson on the opening belter “Rock ‘N’ Roll Outlaw”. The guitars are running on adrenaline, the drums don’t give a fuck who’s listening, and Angry is unapologetically ruthless. “That’s why they call me one of the boys”, he yells as a toast to mayhem. Rose Tattoo is the seminal self-titled rock‘n’roll album of the Eighties, produced by the legendary Vanda & Young. Mick Cocks’ staunch and aggressive guitar playing underscores the record with an unnerving sense of doom. Ian Rilen, of punk band X infamy, injects basslines that vibrate out of control while authoring the anthem of the record, “Bad Boy for Love”. Dallas ‘Digger’ Royall’s rhythm keeps everyone on their toes while Peter Wells’ slide-guitar nods to the roots of American outlaw blues. This isn’t an album for faint hearts or glasshouses, it’s a manic expression of outsider agony. Angry exits stage, on “Astra Wally”, after singing about coming down in jail and a man with caps in his hat, yelling, “Think! Think! Think! Think! Think! Think!”

Art of Fighting, 'Wires'

Australia’s finest ambassadors of slowcore walked off with the ARIA for Best Alternative Release on the strength of their debut album, beating out the likes of Magic Dirt, You Am I, and Something for Kate. If that might seem like a left-field choice, it’s a testament to Art of Fighting’s patient power. The Melbourne quartet’s chiming guitars, brushed drums, and dreamy vocal harmonies lend subtle dramatic scaffolding to Ollie Browne’s achingly pure tenor, while bassist Peggy Frew contributes her own whisper-soft lead on “I Don’t Keep a Record”.

The band’s signature unhurried pace even picks up near the album’s end, culminating in the sloshing distortion and chanted refrains during the second half of “Just Say I’m Right”. It’s such a gripping emotional climax that a minute-long instrumental is required afterwards by way of comedown. If Frew is arguably better known as a novelist now—and drummer Marty Brown as a producer—Wires remains a calm and controlled introduction to slowcore, putting the band on even footing with US peers Low and Red House Painters. And when Art of Fighting returned after a dozen-year drought with 2019’s Luna Low, it proved that their measured majesty had only improved with time.

Keith Urban, 'Golden Road'

Having earned his Nashville stars and stripes as a songwriter for five years in the early Nineties, Urban was two albums deep into his solo career when it came time to write Golden Road. Never one to rest on his laurels, or the country genre traits that shaped them, Urban’s initial songwriting sessions for this record featured a drum machine, a six-string banjo, and a goal to transcend the traditional frontiers of country music. Self-produced, raw, and impeccably constructed, the songs marked an indelible change from his previous work and signalled Urban’s music genre-fluidity to come. When it came time to preview a few songs to his record label, an executive missed the point entirely and cut him down with the words, “I just don’t hear anything that you should put on your record”. Trusting his own intuition, Urban took a leap of faith and included all six songs on the album anyway. Three singles hit number one on the US country chart (“Who Wouldn’t Wanna Be Me”, “Somebody Like You”, and “You’ll Think of Me”), and the album went triple Platinum in the US.

Sticky Fingers, 'Land of Pleasure'

A friend once retrospectively described Land of Pleasure as the handshake muscle meme (from 1987’s Predator) to high school subcultures.

Being a teenager is atomising and lonely. In 2014, Sticky Fingers released an album that offered a sense of unity. It spoke to our unconscious desire for a sense of both brotherhood and anonymity. A carefree, loose-limbed liberation from the pains of being a self-aware young person. For many of us, it was the shared soundtrack to our rumspringa.

Land of Pleasure, in all its louche, hedonistic swagger, got through to us. A delirium-like montage of rock, reggae, psychedelic, Britpop, and electronica, the record invited us to check out from our angst, and lean into euphoria.

One need look no further than the album centerpiece, “Gold Snafu”, with its jubilant, ecstasy-high chorus. Visit any live performance of the track and you’ll be greeted by a cosmic scene of thousands of sweaty, bucket hat-clad, adulating teenage faces, belting “I see the sunrise getting high” with white-hot intensity.

Irrespective of where Sticky Fingers stand in culture, it would be dishonorable to our teenage memories not to recognise Land of Pleasure for what it was: a big, warm, uplifting paean to the

Tex, Don & Charlie, 'Sad but True'

The teaming in 1993 of consummate Beasts of Bourbon/Cruel Sea frontman Tex Perkins with Cold Chisel songwriter/keys-player Don Walker seemed like a masterful meeting of generations at the time. But it was a far more nuanced affair than it appeared. Guitarist Charlie Owen was a common element to both—and has been a foil to Perkins ever since—and following an acoustic recording for triple j and some open-minded studio sessions, the trio locked in with a collection of unplaced gems and new ideas. Walker’s “Danielle”—previously heard as a Chisel tune sung by Ian Moss called “Janelle”—provides a good example of the shared ethos, ideas, and vocals (Perkins duets) on offer. Produced by Tony Cohen, the mood is late night, dollar-too-short-a-minute-too-late-and-several-drinks-too-many. “Fake That Emotion”, “Redheads, Gold Cards and Long Black Limousines”, “The Girl with The Bluebird”, and “What I Done to Her” sound and do exactly what it says on the tin. Owen’s instrumental “Dead Dog Boogie” somehow falls in between to wake everyone up, leaving everything all over the place but especially inside one’s ears. The combination of characters here is so rewarding it’s been revisited twice, but only (oddly) in subsequent Years of The Dragon. Natch.

The Drones, 'Gala Mill'

With Gala Mill, The Drones expanded their vision to the feverish, eloquent rock’n’roll dirges that would go on to define their legacy in Australian music.

From the opening of the modern classic “Jezebel”, The Drones take flight and refuse to come down. It was from this track onwards that the band would perfect the volatile musical chemistry that courses through their sound and channel it into something transcendent.

Narratives twist and turn, peppered with references to beheadings, classical literature, colonial barbarism, and apocalyptic fantasies. Gareth Liddiard is an incomparable lyricist, turning songs into explosive vehicles for poetry.

With the vigour of a deranged preacher speaking in tongues, Liddiard’s vocal performance remains unforgettable. He warbles and croons, whispers and screams, as the powerhouse lineup of Fiona Kitschin (bass), Mike Noga (drums), and Rui Pereira (guitar) rise and fall with ferocious intent. Noga’s cataclysmic drumming—pushing and pulling the band to hair-raising crescendos—crash like violent waves in an unforgiving sea of noise. Fitting, for an album recorded in an abandoned mill in Tasmania, isolated from the mainland by the tempestuous Bass Strait.

The Drones are a once-in-a-generation band. With the release of Gala Mill, Australia began to understand why.

The Hummingbirds, 'loveBUZZ'

In the grand scheme of things, Sydney outfit The Hummingbirds were only around for a short time, releasing two albums and two EPs across five years: but any dedicated fan will tell you that they didn’t waste a single second. While a handful of singles peppered their early years, it was 1989’s loveBUZZ that took centre stage, with the group’s debut full-length album hitting number 31 on the local charts and eventually going Gold. Bolstered by the powerful songwriting of late guitarist and vocalist Simon Holmes, and the mesmerising talents of vocalist and guitarist Alannah Russack, The Hummingbirds were an unassuming powerhouse of romantic lyricism and forceful, yet tender, jangly guitar pop. To this day, it’s impossible to find an Australian artist who doesn’t feel moved by the likes of songs such as “Blush” or “Word Gets Around”, or find themselves studying the stunning melodicism of tracks such as “Alimony”. The Hummingbirds might only have existed for a short while, but they set the blueprint for what indie pop should sound like during that time.

Died Pretty, 'Free Dirt'

Just two years before their debut album arrived, Sydney’s Died Pretty issued their ten-minute single, “Mirror Blues”. A lengthy composition which felt like a psychedelic jam at times, it was an ambitious release, and gave fans an idea of what the future might sound like. By the time it came to record 1986’s Free Dirt with Radio Birdman founder Rob Younger, Died Pretty had refined their sound, turning what sounded like a burgeoning Sixties-inspired garage rock outfit into a collective who seemed wiser than their years. The joyful exuberance of singles such as “Stoneage Cinderella” and “Blue Sky Day” seamlessly sitting alongside the likes of “Life to Go (Landsakes)” which, in addition to featuring the great Louis Tillett on piano, saw frontman Ron Peno deliver a stunning vocal performance which would have seen Jim Morrison himself become a Died Pretty diehard. Elsewhere, the lengthy “Next to Nothing” harkened back to the band’s early material, with the accomplished songwriting descending into a cacophonous breakdown mid-song, only to emerge out the other side, a familiar melody returning as if nothing had happened. Much like Died Pretty themselves, it would lull you into a full sense of security, leaving you unable to witness the majesty of what had occurred until you had time to reflect on things.

The Living End, 'State of Emergency'

Having already cemented themselves as beloved fixtures of the Australian rock scene, The Living End once again stormed the charts with their fourth studio album, which embodied the Melbourne band’s trademark unapologetic punk rock energy.

More musically diverse than their previous albums, State of Emergency showcased the band’s versatility as they enlisted familiar punkabilly elements reminiscent of their debut album while incorporating bursts of rapid-fire electric guitars and big vocal hooks in tracks that were carefully contrasted by slower, melodic tunes peppered throughout the record.

After receiving a nomination for the coveted J Award for Best Australian Album in 2006, guitarist Chris Cheney told triple j of the nod: “We put everything we had into this album, we really wanted it to stand out from the rest of the albums and to be really special for us, and it was.”

Their second chart-topping record, State of Emergency spawned four Top 40 singles, with the likes of “Wake Up” and “What’s on Your Radio?” peaking at number five and number nine on the local charts, respectively. Though fans already knew The Living End were unstoppable local rock icons, State of Emergency proved they were going to be around for years to come.

Clouds, 'Penny Century'

In retrospect, 1991 was quite a year for incredible albums. Penny Century may not be as hyped as Nevermind or Achtung Baby, but Sydney band Clouds shouldn’t be overlooked. Their debut is a triumph of precision songwriting and once-in-a-career musical chemistry. Most bands lack even one truly gifted songwriter—Clouds had two, Jodi Phillis and Tricia Young. The Pixies’ influence was evident with their spiky guitar work, turned up loud (it was the era of grunge), as was a nod to the Cocteau Twins’ otherworldliness. There was also the undeniable DNA of classic pop-rock—they loved Glen Campbell, as evident in the country-tinged melancholy of “Pocket”. The pair’s distinctive songwriting styles complemented each other, and the band’s not-so-secret weapon was how their voices blended together, adding extra harmony. “Hieronymus” created a lush but sinister world before your ears. “Anthem” went from lullaby to mosh pit in seconds, honouring that quiet/loud Pixies dynamic. It was a very Nineties indie tactic to release EPs before an album, and while their biggest hit—the bonkers-but-brilliant-and-brief “Souleater”—made the journey across from their Loot EP, in hindsight 30 years on, including stunning EP cuts “4pm” and “Cloud Factory” would have seen Penny Century make a near-flawless first impression.

The Cat Empire, 'Two Shoes'

For a band like The Cat Empire, the notion of falling victim to the dreaded “second album syndrome” must have been an all-too real one. After all, with their early years spent curating a fervent following throughout their native Melbourne, their 2003 debut was a huge achievement for the jazz-funk outfit. But once you’ve delivered a stunning debut and taken the local music scene by storm, what comes next? How do you top a career-starter like that? For The Cat Empire, their next step was simply business as usual, crafting another instant classic that felt representative of experiencing the group on the live stage. Recording Two Shoes in Cuba in late 2004, and releasing the record in April of 2005, the group’s second album felt like a continuation of what fans had come to expect from the Victorian collective, albeit with more introspection mixed in with the high-energy classics. While radio found itself turned onto singles like “Sly” and “The Car Song”, cuts like the title track, along with “Miserere”, or live-favourite “Sol y Sombra” proved The Cat Empire hadn’t lucked out with their debut, they were just a music-making machine who had only begun to hit their stride.

Sampa the Great, 'Birds and The BEE9'

What’s most surprising about Birds and The BEE9 is that Sampa Tembo (aka Sampa the Great) herself regards the incredibly refined and impactful collection of songs as a mixtape, rather than a full album. Nomenclature aside, what Tembo created alongside producers Sensible J, Alejandro Abapo, and Kwes Darko is nothing short of exceptional.

Birds and The BEE9 is art and artist in perfect union. Across 13 tracks, the Zambia-born, Botswana-raised Australian blends genres, influences, collaborators, and languages from across the globe to both directly and indirectly announce to the world who Sampa the Great is.

Jazz, hip-hop, and electronic elements merge with sub-Saharan rhythms. There’s chanting, singing, rapping, and spoken word. There’s English, Nyanja, Bemba, Swahili, and Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara.

Many a great artist would struggle to incorporate so many seemingly disparate elements into a single cohesive work, but Sampa and her collaborators make it seem effortless. It’s a reflection of an incredibly talented artist who is confident in, and proud of, who they are. Birds and The BEE9 is a rich tapestry of cultures and musical art forms, and a vital standout entry in the vast library of great Australian music.

Ratcat, 'Blind Love'

By the time Ratcat had managed to hit what many would call the “big-time” in the early Nineties, the group had already been at it for five years, with debut album This Nightmare being largely overlooked by the charts and music-buying public. However, seemingly inspired by a signing to the nascent rooArt label, Ratcat burst onto the mainstream scene in late 1990 with their Tingles EP, which found its way to the top of the charts early the next year. The seeds of success had been sown, and while they were still a hot topic on the local music scene, second album Blind Love was released, suddenly making Ratcat one of the biggest success stories of the year. Solidly aligning with fellow noisy power-pop bands of the era, Blind Love wasn’t just a pure indie-rock album, but rather one that still found itself heavily influenced by elements of post-punk and psychedelia along the way. While the album might have been overshadowed by megahits like “Don’t Go Now”, “That Ain’t Bad”, and “Baby Baby”, it’s hard to find a single track on the record that isn’t deserving of having been a single. And hey, when you’re only two albums deep and making chart-topping records full of potential hits, well, that ain’t bad.

The Saints, 'Prehistoric Sounds'

Prehistoric Sounds was the final offering by the original Saints ensemble, fronted by Chris Bailey and Ed Kuepper. It was a mature stroke; raw, soulful, and less distracted than the garage punk of (I’m) Stranded. “They opened up the doors for all us future punks,” laughs Mitch from punk outfit Low Life, on a call with Rolling Stone Australia. “It’s got that back end of Brisbane late Seventies sound with just a nip of that Fun House (The Stooges) energy.” At the crossroads of post-punk and rhythm & blues, The Saints achieved a telling portrait of the Bjelke-Petersen era. “Thirteen hot nights in a row / The cops drive past and they move slow / A million people staying low,” goes the serenading ode in “Brisbane (Security State)”. The tone was gothic and doomed, juxtaposed with sleazy horns, brassy arrangements, and heavy-set drums that were wrestling with jazz. Algy Ward from The Damned bolted the record down with a sobering bassline. Ed Kuepper’s Bo Diddley-inspired guitar was toying with the future direction of his experimentations. And Chris Bailey’s voice, for all the turbulence that was vibrating beneath The Saints, held the deteriorating atmosphere together. His final line, an Aretha Franklin cover, pleads, “I want you to save me right now”.

The Scientists, 'Blood River Red'

It’s a little amazing to think about what The Scientists managed to pack into their initial nine-year run, with so many influential records coming out of this collective of artists. Having evolved out of The Invaders in the late Seventies, the Kim Salmon-fronted WA group gave fans a taste of their powerful punk sound by way of their 1981 debut album, The Pink Album. However, an outfit such as this couldn’t stick around forever, and following a one-month split, Salmon—along with bassist Boris Sujdovic, guitarist Tony Thewlis, and drummer Brett Rixon—formed a new iteration of The Scientists and moved to Sydney. This time though, their sound was far removed from what it had been, with a swampy post-punk sound now at the forefront of their creativity. A testament to their versatility though, it was their 1983 mini-album Blood Red River that gave a greater picture of this new version of the band. Armed with the same fiery energy that they had previously utilised, Blood Red River saw The Scientists take things to the next step, with the likes of “Burnout”, “When Fate Deals Its Mortal Blow”, and the title track showing a band with an inimitable passion and ferocity, and continuing an already astounding legacy.

Thelma Plum, 'Better In Blak'

Thelma Plum’s debut album is an infernal, penetrating profile of a proud Gamilaraay woman who has had the core of her being tested, attacked, disregarded, and tokenised. The title track, while not the album opener (that honour goes to velvety highlight “Clumsy Love”), sets the tone for the entire collection. Written in a London Airbnb with the record’s producer and co-writer Alexander Burnett, the track was an in-the-moment digestion of an incident the night before. Plum was laying down vocals for “Do You Ever Get So Sad You Can’t Breathe” at Burnett’s South London studio when her phone received a barrage of abusive texts. The racist and misogynistic hate was sparked by an altercation between Plum and the member of a Sydney band. The ugliness of the response almost sent her back home to Australia. But as the first line spilled onto paper (“Do you know what it feels like? / To get calls in the middle of the night?”), Plum became ready to throw the listener into the darkest parts of her life. Then, through media and slacktivist takedown tracks like “Homecoming Queen” and “Woke Blokes”, she brings the listener out the other side with the same resilience that has carried her through. A manifesto with a lush alt-pop soundbed, the album has since taken on a life of its own—lyrics have even been quoted on banners at local Black Lives Matter rallies. Better in Blak is proof Thelma Plum can move feet as well as minds.

The Masters Apprentices, 'The Masters Apprentices'

Released in 1967, The Masters Apprentices’ self-titled debut album grew out of a successful EP for the Adelaide based rock group, Undecided.

Capitalising on the success of the four-track record, the band’s label—Astor Records—were quick to make the decision that the EP should be fleshed out into a full album.

The original record put The Masters Apprentices on the map; local support swelling around their blend of psych influences and rich guitar work, not to mention pointed lyricism that set them aside from other acts of the time.

In particular, their track “Wars or Hands of Time” has become known as the first Australian pop song to directly tackle the Vietnam War—the single being released in an Australian climate newly introduced to conscription. It brought more attention to the group and with continued success currying outside Adelaide, The Masters Apprentices propelled the band to the east coast, and then national fame.

The record as a whole, provides a great insight into how Sixties rock music was changing the tapestry of pop music in Australia, with The Masters Apprentices cleverly incorporating soul covers (Otis Redding’s “My Girl”, Bo Diddley’s “Dancing Girl”) in with originals that represented natural songwriting skill.

Frenzal Rhomb, 'A Man's Not A Camel'

“Frenzal Rhomb are not a very good band,” says a Japanese voice at the end of the 26-second track, “I Know Why Dinosaurs Became Extinct”. However, even a cursory listen to the other 14 songs (or 15, including the hidden track) shows that A Man’s Not a Camel might just be Frenzal Rhomb’s best work. Emboldened by the success of their third album, Meet the Family, two years prior, the Sydney punk outfit’s 1999 record captured them in one of their most productive periods. Taking over alternative radio with singles such as “Never Had So Much Fun”, “You Are Not My Friend”, “We’re Going Out Tonight”, and the refreshingly-reflective “I Miss My Lung”, it’s hard to look at A Man’s Not a Camel as anything but a best-of, or at least a collection of what made Frenzal Rhomb one of the defining punk bands of Australia in the Nineties. Even the overlooked cuts such as “Let’s Drink a Beer”, “Methadone”, or “Do You Wanna Fight Me?” show that Frenzal Rhomb weren’t just about invading the charts and going Gold with a fun, exhilarating record. They were writing some of the best songs of their career. It’s enough to make anyone chant, “Go Frenzal, go!”

Boy & Bear, 'Moonfire'

Australia’s answer to Mumford & Sons, it’s fitting that Sydney’s Boy & Bear supported the Brit-folk outfit on their Australian tour in 2010 before releasing their breakout debut album, Moonfire, the following year.

Recorded in Nashville, the quintet’s bluesy roots shine through. Having worked with some of the world’s biggest artists (The White Stripes, The Strokes, U2), renowned producer Joe Chiccarelli’s expertise helped polish the 11-track album into a stunning amalgamation of folk, pop, and rock. Soaring them into the global spotlight, Boy & Bear raked in accolades at the 2011 ARIA Awards, scoring five wins including Best Group, Album of the Year, Best Adult Alternative, Breakthrough Artist (Album) and Breakthrough Artist (Single) for album standout “Feeding Line”.

With infectious instrumentation comprising (but not limited to) multiple guitars and a banjo to boot, Moonfire provides many a knee-slapping, foot-stomping moment with tracks like “Golden Jubilee” and “Milk & Sticks”, between more reflective, sway-inducing numbers like “Big Man” and “Part Time Believer”.

It’s obvious the band began as a solo project for frontman Dave Hosking, his charming vocals the prominent carrier of each song on Moonfire. The singer-songwriter’s soulful melodies flow over an exceptional layering of instruments, through balanced and comforting harmonies, bringing together a cohesive collection of soothing, cheerful track

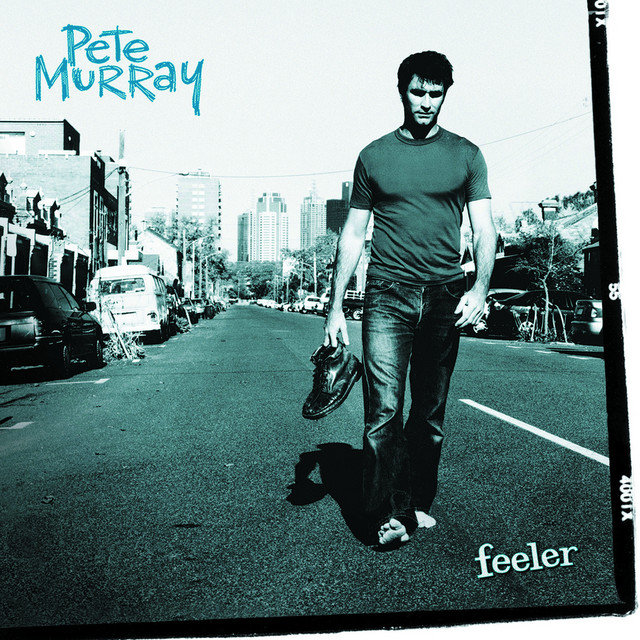

Pete Murray, 'Feeler'

Despite the major success of Feeler, Pete Murray admitted he had never listened to the record in its entirety until eight years after its release.

“When it was done I just couldn’t hear anything good about it,” he revealed to Scenster during its ten-year re-release campaign. “I couldn’t stand it. I would try and play it from start to finish and would get to track three or four and have to turn it off because I hated it.”

However, it was Powderfinger’s Darren Middleton who helped him come around, reminding him of the quality and impact that the record had, and urging Murray to reassess the album.

These days, he’s much more appreciative of the record that helped him become a household name, thanks to the eclectic pop-rock of tracks such as “Lines”, “Bail Me Out”, and the enduring “So Beautiful”. After all, the album went six times Platinum and had enough mellow maturity to inspire a generation of incoming troubadours.