Festival fashion is all about chanelling the sentiment of the times to express oneself with style. Clothing brand Ben Sherman has accompanied the history of rock with designs that although always feel contemporary, pay homage to the rich heritage behind them. Rolling Stone partners with the iconic brand to take a deep dive into the evolution of the festival outfit and how it has developed parallely with the music.

Throughout the ages, technology, music, and fashion have transformed together in a dance that although not always pretty and synchronized, serves as a faithful reflection of the spirit of each era.

Just in the last hundred years, we’ve seen how technology has turned live music, once an intimate enterprise reserved for halls and auditoriums, into a grand spectacle experienced by hundreds of thousands. At that same time, something seemingly innocuous as a shirt has gone from being a formal garment reserved almost exclusively for men, to becoming a universal clothing item used as an extension of our individual identity.

One of the very first expressions of music-inspired fashion in the 20th century, and the predescessor of the “band T-shirt” was the so-called “bobby soxers” look, associated with teenage super fans enamoured of smooth-voiced crooners like Frank Sinatra.

“Bobby-soxers [in the 40s] began the trend of writing the name of their favorite singer across the back of their jackets – a flourish of Frank, or a swirl of Sinatra.” said to The Guardian Johan Kugelberg, author of the book Vintage Rock T-Shirts.

Up to the mid-20th century, live music was an affair almost exclusive to working adults, those with the spending power and social independence to buy tickets, drink alcohol and attend to late night events. But the apparition of amplified instruments, —a circumstance that gave birth to rock’n’roll— took live music out of ballrooms and brought it to smaller, unconventional locales, introducing it to a much younger demographic. This new, imperfect electric sound exploded in the ‘50s, instantly appealing to teenagers eager to listen to something completely opposite to what their parents liked. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s new deal and post-war recovery had set the United States on a path of relative prosperity, one that granted these rebellious youngsters enough purchasing power to buy their own tickets, their own records, and dress however they wanted. The hearts, ears, and shirts of audiences of the jazz age were not the same as those of rock.

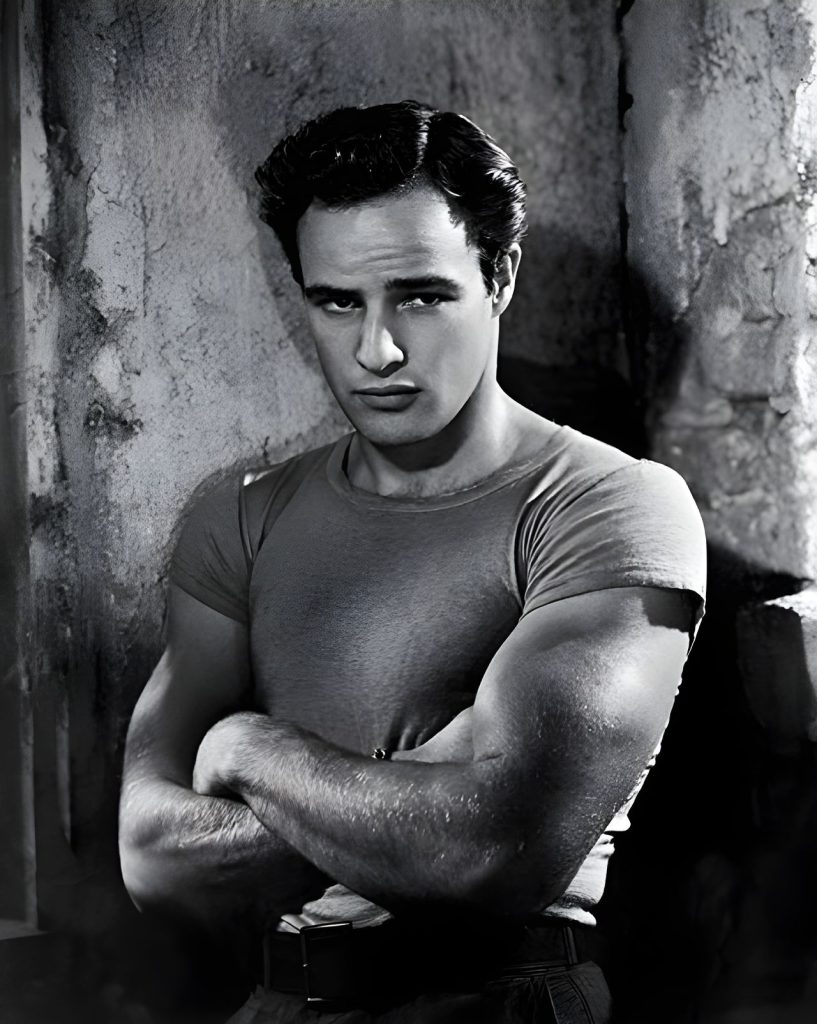

Inspired by silver screen trendsetters like Marlon Brando and James Dean, youth in the ‘50s started adopting this modest undergarment called the “T-shirt” (baptized by Scott Fitzgerald in This Side of Paradise). Wearing a T-shirt was rebellious, sexy, almost vulgar, after all, it was just a flimsy layer of underwear for christ’s sake! And that was precisely the appeal.

Capitalizing on this teen defiance, in 1956 an Elvis Presley fan club decided to offer Elvis-branded T-shirts, the first musical performer to open the Pandora’s box of endless merchandising craze that we see today.

Marlon Brando wearing a T-shirt in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ (1951) ©Warner Bros. Pictures

Young people loved jazz too though, —I mean, how could they not?— especially the edgier sounds of artists like Charlie Parker and Miles Davis. The Soho jazz boom was a short period around ’58-59 where a modern jazz scene developed in London’s Soho district. British jazz fans, who grouped around local artists like Ronnie Scott and Tubby Hayes, dressed with button-down shirts and suit jackets, similar to those of their musical heroes.

Their attire contrasted with that of the rockers, a working-class urban tribe that developed parallely, molding itself after American artists like Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran. Rockers were content with a cheaply made white T-shirt, a leather jacket and a pair of jeans.

New Delhi, September 23, 1963: Duke Ellington at a demonstration at the Triveni Kala Sangam.

In the late ’50s, London-based Jazz fans had only two options, they either spent an arm and a leg on imported clothes or settled for poor quality local knockoff brands.

Ben Sherman, a Brighton-born entrepreneur saw an opportunity and took it with both hands. He filled that demand for Oxford-collared American button-down shirts by improving the product, utilizing high-quality materials and superior stitching. In 1963 he founded Ben Sherman, a brand that was quickly adopted wholeheartedly by that new youth subculture that emerged from the jazz scene; the mods. (as a curious sidenote, Ben Sherman retired in 1975 and moved to Australia)

Mods, from the word “modernist,” were young bohemians, mostly students, who rejected traditional British working-class culture and sought to develop a new one, one that revelled in hedonism and consumerism.

They were interested in avant-garde art and film, with a special enthusiasm for fashion. They gravitated around coffee bar culture and aside from jazz their musical tastes were a mix of R&B, Motown and blues-oriented rock. They listened to bands like Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, The Velvelettes, and later on, The Who and The Kinks.

Rockers, much more primal in their aspirations, mocked their pretentiousness and retaliated violently against them, sparking teenage skirmishes that would be covered as infamous riots by the media of the time. These clashes would be immortalized by The Who’s 1973 concept album, Quadrophenia and the 1979 film of the same name.

At the start of the ‘60s, electronics company Shure had introduced a new iteration of their Shure Unidyne series, an improved microphone with high volume tolerance that allowed live music to be played in large, open-air spaces. Young audiences had already chosen their own musical genre, their own way of dressing, and now, they were the first generation in history to experience mass outdoor concerts.

Newport Folk Festival appeared in 1965, the Monterey Pop Festival followed in 1967, and later on, Woodstock in 1969. Superstars like Jimi Hendrix, the Who, and Janis Joplin, played for the first time ever in front of hundreds of thousands of people.

In a time of the Cuban missile crisis, the Vietnam War, and the Civil Rights Movement, hippie culture represented young people’s necessity to break with previous generations, reject traditional views of family, state, and culture, and advocate for global peace. Hippies championed sexual liberation, showed a renewed interest in spirituality, and embraced environmentalism. The generation of “flower children” promoted the use of hallucinogenic drugs and embraced folk and psychedelic rock.

It’s not a negligible anecdote that despite there being more than 400,000 people reunited at Woodstock, and taking into account the precarious security measures in place at the time, there were no notable incidents of violence.

Bright, psychedelic colors dominated festival fashion, with ample use of tie-dying thanks to the widespread use of plastisol and screen printing techniques.

“All this tie-dyeing can be augmented by tie-bleaching. It’s tie and fire up the bleach. It’s bleach and water. You put on industrial gloves and you put it in quick and out quick. You are trying to keep it from burning holes. It was a magic sort of medieval and dangerous.” explains singer/songwriter John Sebastian of rock band The Lovin’ Spoonful, “everything was tie-dyed [at the time], sheets, blankets, clothes, shoes, underwear.”

Sebastian’s tie-dyed denim jacket and Joe Cocker’s multi-colored T-shirt became part of the historic iconography of Woodstock and the summer of love as a whole.

Crop tops have been a feature of women’s fashion going back to the Egyptians and ancient India, a garment introduced into the West when it appeared at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. During the festivals of the ‘60s, midriff-baring tops were adopted as a festival wardrobe essential, a symbol of women’s sexual liberation and the vindication of genre equality.

Aesthetics gravitated towards a fusion of global styles, pairing denim with traditional world garments like Bangladeshi Kantha gowns and Peruvian alpaca shawls. Issues of cultural appropriation were of course part of the most thoughtful conversations of the time in universities around the world, but the pull of escapism was just too strong, and audiences didn’t really care. All they wanted was to have fun.

The ruckus of electric guitars could now be heard by thousands of people at the same time and the phenomenon of the massive outdoor music festival went global. First with the Reading National Jazz and Blues Festival in 1961, and afterward with the Isle of Wight Festival in 1968, and the Pinkpop Festival in 1970, Europe had its own outbreak of counterculture soirees, catapulting acts like Jefferson Airplane and Bob Dylan as international stars. Flower power aesthetics spread to corners of the globe.

Impressionable teens were not the only ones paying attention to the revolution. Personal expression and peace and love aside, T-shirts were also walking billboards begging to be used as marketing tools. Grateful Dead promoter Bill Graham saw the opportunity, and with his San Francisco-based company Winterland Productions launched the concept of the concert tee. Artwork by Allan “Gut” Terk, a Hells Angel and graphic artist, and Stanley “Mouse” Miller began to appear in the front of luscious T-shirts that featured the band’s touring calendar printed on the back. With screen printing technology enabling shirts to be printed in volume, it was a simple, yet brilliant form of marketing that changed the music industry forever, opening new revenue avenues for performers and record labels. Concert T-shirts became beloved band merchandise, valuable memorabilia, and part of a fan’s personal identity.

Too Fast To Live, Too Young To Die

By the ‘70s, the promises of prosperity from the post-war years had failed to deliver. Rising unemployment, urban crime, and steep inequality had begun to seep through the cracks. Angry, disaffected teens were unsatisfied with family, state, and school, all institutions that seemed like failed monoliths of a decaying society. People were outraged at their beloved idols turned into safe pop superstars that nonchalantly glanced at a destroyed society from their corporate ivy towers.

In Los Angeles, New York, and London, a new sentiment was brewing, a novel brand of counterculture that distrusted icons and any figure of authority and privilege. Punk culture was an expression of this disappointment, the manifestation of a generation that wanted to destroy everything that was wrong and rebuild from the ground up.

In London, Malcolm McLaren, an art school dropout, and Vivienne Westwood a schoolteacher devised a cultural uprising. More interested in the ruggedness of early ‘50s rock’n’roll than in the laid-back, ethnic chic aesthetic of the Woodstock generation, they resorted to tartan, leather, and safety pins. They designed vests with zippers as windows to the nipple, pants sprayed with glitter glue. Little key locks and bleached chicken bones were now accessories.

Using shirts as a vehicle for political expression, Westwood and McLaren ripped and burnt T-shirts, printing on them incendiary, insulting words like “SCUM” and “PERV.” Shirts were not billboards to promote products but to incite outrage.

Concertgoers unapologetically carried T-shirts emblazoned with Jaime Reed’s anarchist designs like his famous manipulated photograph of Queen Elizabeth II, or slogans like “Accidental Anarchist” and “A Brick Will Do the Trick.”

At the same time, improved amplifier and public address system technology opened the doors to arena rock. Blues-based bands descending from The Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin seemed a perfect fit, loud volume and exaggerated distortion ideal for all those acts that explored the roughest sound spectrum of rock; heavy metal. Bands like Black Sabbath and Deep Purple ignited the craze for black T-shirts and skinny jeans, now a staple of metal fandom.

The 70s also saw the creation of some of the most famous iconography of rock, symbols, and logos that would emblazon shirts to our days. John Pasche designed the now ubiquitous “tongue logo” for The Rolling Stones, AC/DC’s “lightning bolt” was created in ‘77, and in 1978 New York artist Arturo Vega came up with the infamous Ramones “Presidential Seal” logo.

Parallelly to the emergence of punk and heavy metal subculture, a very different musical insurgency was being born in the poverty-stricken streets of the Bronx.

In the early 1970s, the Bronx in New York was struggling with high unemployment and gang violence. With no access to disposable income for things like instruments or musical education, turntables and records seemed like alternative tools for musical expression. DJs provided a safe space where people of all factions could ease their tensions and anxieties around the power of music. “It all started with the DJ, they brought the parties, and the parties gave people an escape from the madness of the Bronx,” says Alien Ness, legendary b-boy and hip-hop precursor.

The “breakdown” is a part of a record where all the music “drops down,” leaving only the beat. DJ Kool Herc, a popular Bronx personality at the time because of his frenetic parties and impeccable musical taste, noticed that people went bonkers when he played these percussion-heavy sections of songs. “These beats were so hype and so frantic that when the music dropped out and it was just the beat, everybody would go off,” reminisces Grandmaster Caz in the 2002 documentary The Freshest Kids.

Looking for ways to trigger his crowds into a dancing frenzy, DJ Kool Herc devised a way to extend these beat sections using two turntables and two copies of the same record. As one record reached the end of the “break,” he cued the second one back to the beginning of said break, allowing him to extend the section for as long as we wanted.

“I would call that particular part of the music the merry-go-round” Kool Herc explains the trick in his own words, “because I’m gonna take ya’ to the merry-go-round back and forth giving you no slack.”

Hip-hop was born, and there was no turning back. Other DJs like Grand Wizzard Theodore and Afrika Bambaataa started experimenting with new sounds and techniques, expanding the vocabulary of this nascent genre, and converting turntables into bona fide musical instruments.

At the time, the NBA was one of the most notable cultural spaces where African American communities got to reunite around their idols. Players like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Bob Lanier were tearing courts at will, sparking the imagination of a generation. Sportswear, in particular Adidas shoes and tracksuits, spilled from courts to the streets. Many of those very first DJs adopted the sports look, creating an iconography that would become part of hip-hop culture. Those images of Grandmaster Flash wearing red and black tracksuits have become instilled in collective memory, now a part of history.

“There was a doctor in our neighbourhood named Dr. Deas, and he was like this community activist dude.” explains the legendary hip hop group Run-DMC, “He even wrote a little pamphlet and he put it around the neighborhood called ‘Fellon Shoes’, where he was saying [that] kids and youth in the streets that wore Lee jeans and Kangol hats, and gold chains, and Puma’s and adidas without shoelaces were the thugs, the drug dealers and the lowlifes of the community.”

To vindicate this young generation of African-Americans, the band decided to write a song that put these communities in a different light. “Let’s do a record about our sneakers; let’s talk about the sneakers that we wear on our feet, but let’s put a positive spin on it to throw it in the face of this Dr. Deas, who’s trying to judge the youth just by appearances.” Like, you can’t judge a book by its cover. We’re young; we’re educated. A lot of us go to school; a lot of us have jobs. A lot of us, even though we look like our peers in the neighborhood – but you can’t judge everybody by that.”

The hit ‘My adidas’ led to one of the very first music-brand collaborations ever, including a clothing line with the Adidas Superstar with the group’s logo.

The Beastie Boys perform their headlining set on the main stage at Voodoo 2004 ©Luigi Novi

Turntables, the invention of synthesizers, and the popularisation of cheap Casio organs and other similar instruments were part of the establishment of a new type of sound, electronic music, –a child of Musique concrète of the ‘40s– one produced by machines, in contrast to traditional means.

House, the invention of black DJs from Chicago’s underground club culture in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s was an extension of this new musical lexicon, one with its own codes and aesthetics. By the end of the ‘80s and start of the ‘90s, a flurry of subgenres like techno and trance began to appear, partygoers in warehouses and specialized clubs instilling their own brand of fashion, one that featured boiler suits, phat pants, and overalls.

The Times They Are A-Changin’

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, the unification of Germany, the conflicts in the Balkans, and the Gulf War… the decade of the ‘90s kicked off with major socio-political events that established a new post-cold war global order. In this turbulent context, the sleepy, cold coastal town of Seattle would witness what is perhaps the last musical revolution of our times, one with parallels to the punk explosion of the ‘70s.

Bands from around the U.S. stopped touring in Seattle because the trip way up north became economically inviable. This sudden demand for live music was filled by a myriad of local acts that jumped at the opportunity to fill the void. With little competition from outside performers, the low pressure for commercial success allowed these new young bands to experiment at leisure with different styles and techniques. As these bands mostly recorded in the same makeshift studios and often even shared members, a distinctive, local sound began to emerge. With no clear objective in mind, musicians began to fuse elements of punk and heavy metal in the most unorthodox of ways. The term “grunge” became a cheesy, self-depreciative euphemism to describe any sound that felt “extreme”.

Just as punk was born out of rejection towards the “elitism” and musical extravagance of prog rock and psychedelia, rockers in Seattle had a similar knee-jerk reaction, this time around against the eye-blinding glitz and artificiality of glam metal, and the pomposity of the mega pop stars of the ‘80s.

Grunge aesthetics were an outright rejection of glamour, opting instead for laid-back, practical garments like flannel shirts and ripped jeans. Young people in the early nineties adopted long hair, oversized T-shirts, and hole-ridden checked shirts, the more disheveled the better. Far from haute couture boutiques, brand obsession, and catwalks, grunge fashion opted for ill-fitting, gender-blind thrifted clothes. Women wore combat boots and Doc Martens, pairing them with slip dresses with ripped flannels. Unlike other fashion trends, grunge clothing seeked to de-emphasize the body’s silhouette, calling as little attention as it could. Jewelry was unflashy, and makeup minimal and saturated.

In the ‘90s, the music industry went through a global disruption that left a highly fragmented market with a myriad of genres and niche audiences. In consequence, a multitude of festivals began to pop up throughout the world, catering to a wide range of tastes. H.O.R.D.E. —which stands for “Horizons of Rock Developing Everywhere”— Lollapalooza, Coachella, and South America’s Rock al Parque, put alternative and independent artists in front of massive crowds of hundreds of thousands.

Over in Britain, a less nihilistic scene was developing, one that displayed a renewed interest in celebrating “Britishness,” something not seen since Beatlemania and the swinging sixties revolutions. In contrast to the disenfranchisement of grunge and shoegaze, Britpop was a brand of alternative rock that was upbeat, catchy, and hopeful, an amalgamation of the most successful sounds British music had produced over the last decades. Take into the blender The Beatles, throw in there a bit of Wire, a tad of Ray Davies, and some nods to The Smiths, and you have the basics of the Britpop sound.

It was a movement that exalted the British working class, with references to football and “lad culture.” Blur frontman Damon Albarn and Noel Gallagher of Oasis championed track jackets, football jerseys, and Adidas sneakers. Add JNCO jeans, crop tops, and sunglasses with brightly colored lenses and you have a look that became ubiquitous on streets and festivals all over the world, including the emerging EDM festival scene at the time in events like Creamfields or Mysteryland.

In the 2000s, the internet had already become the dominant form of communication for youth in urban populations around the world. Thanks to social media, festivals became global events, celebrations followed in real-time by millions of people all over. Celebrities had been part of the crowds of concerts since time immemorial, but the general public had no way of knowing the who, where, and when. Now, not only did we have a detailed list of who went where, but we could also follow their footsteps via geo-tagged images and video.

Pictures of British actress Sienna Miller at Glastonbury in 2004 became the talk of the whole world. She was wearing a black frayed mini dress with a coin-studded belt, neon-framed sunglasses, and a pair of Ugg boots. A year later, supermodel Kate Moss was caught showing up at Glastonbury with a pair of hot pants, a glittering Lurex dress, and Wellington boots. That did it. All of the sudden, festival fashion was a thing.

Independent of the music, the venue, or the cultural subtleties, clothing brands found in those viral hits an opportunity to define the festival outfit and offer it pre-packaged to a willing audience.

“The biggest evolution has been the categorization of ‘festival fashion’ itself, now a permanent fixture of the fashion calendar,” Harriet Reed, exhibition research assistant at the V&A museum pointed out in an interview with Refinery29, “The fashion industry jumped on this huge market audience that was now dressing for an event, rather than just the music.”

In the last two decades, festival fashion has been characterized for repurposing previous trends and taking them out of their previous contexts. Oversized sunglasses and pac-a-macs printed with psychedelic mandalas seem callbacks to the summer of love, along with flower crowns, goa pants, and gladiator sandals. Distressed, studded leather jackets take a page from the punk era. What once was a vehicle for individual expression is now a mass-produced costume.

In 2017, celebrity sisters Kendall and Kylie Jenner released a line of T-shirts featuring their faces superimposed over images of historical musical acts including Pink Floyd, Metallica, The Doors, Notorious BIG, and Tupac Shakur.

The move sparked widespread criticism on social media, with Notorious BIG’s estate threatening legal action, and the rapper’s mother, Voletta Wallace reprimanding the Jenners in an Instagram post.

“I am not sure who told @kyliejenner and @kendalljenner that they had the right to do this,” Wallace’s post read, “The disrespect of these girls to not even reach out to me or anyone connected to the estate baffles me. I have no idea why they feel they can exploit the deaths of 2pac and my son Christopher to sell a T-shirt. This is disrespectful, disgusting, and exploitation at its worst!!!”

The T-shirts were eventually withdrawn, but the Jenners were just the tip of the iceberg, a symptom of a disease that goes way back. In 2012, French-Belgian fashion designer Nicolas Ghesquière produced a collection for Balenciaga that repurposed Iron Maiden’s logo font across a black sweatshirt. The following year, Kanye West commissioned Grateful Dead’s merch designer Wes Lang to create rock-inspired artwork for his Yeezus tour. Vetements’ 2016 spring/summer collections repurposed heavy metal iconography in their T-shirts and hoodies to make them look like band merchandise.

In a scenario where every previous festival look has been co-opted and regurgitated, fluorescent tubes and the good ol’ “wear your country’s flag like a cape” seem almost like originals.

Several punters sport Cotton On’s “Festival Shirt” at the 2019 Fomo festival. @James Anthony

Case in point, the hilariously bizarre recent phenomenon of yellow-striped shirts appearing en masse in Australian festivals in 2019. At the time, the garment from Aussie retailer Cotton On was labeled as “festival shirt” on their online catalog, and still today is the first item to pop up when you google those words. Be it by sheer laziness, or a collective act of irony, hundreds of male festival goers ended up wearing exactly the same shirt, as if they were all part of the same bowling team.

What is happening to today’s festival fashion? Nobody knows. After almost two years in which the festival season has been canceled or scaled down because of the COVID pandemic, it seems like audiences are now adopting a survivalist vibe. Cargo pants, camouflaged t-shirts, goggles, gloves, and balaclavas seem more like part of a “protest starter pack” but oddly enough, these garments have been appearing in events throughout the year. A rejection of fast fashion, or a manifestation of the social tension of the times?

One thing is for certain, be it The Great Depression, World Wars, or the COVID pandemic, the party never stops. We, puny, but marvelous humans have always come out of the darkest times to create better, brighter worlds. In Australia, the summer festival season is around the corner, a new chance to love, dance, and live the best life we can live. And what better than to do it with style? If you’re looking for the ultimate festival shirt, one that has been part of the history of music, shaping fashion along the way, look no further than Ben Sherman, the original since 1963. Explore their site and check out their current Festival Styles collection here.