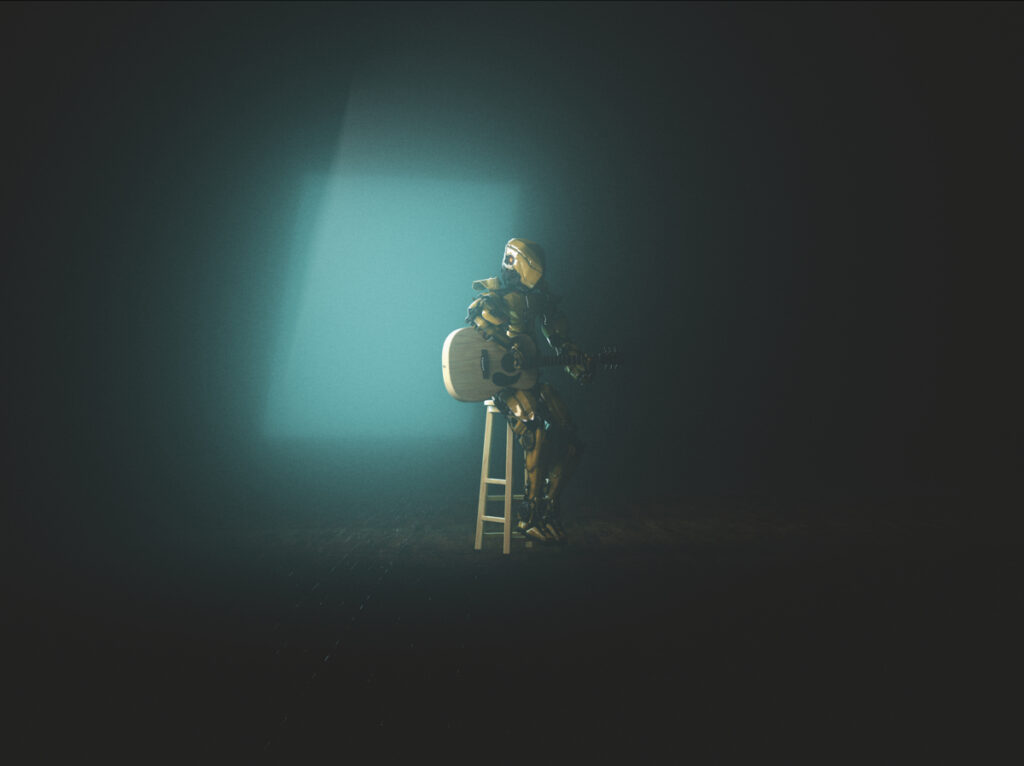

ILLUSTRATIONS BY ANTHONY CALVERT

Can AI put an end to human creativity? What Dr Jürgen Schmidhuber - who some call the "Father of AI" - tells us should be cause for concern

During recent contract negotiations between the Writers Guild of America (WGA) and the Hollywood studio and streaming system, one thing became clearer than ever before: widespread fear exists among writers over the threat posed by Artificial Intelligence (AI) to their craft and livelihoods.

“This is an existential crisis for writers,” Jamey Perry, vice chair of the WGA’s Disabled Writers Committee, told Reuters. She certainly wasn’t alone in this assessment.

The overarching fear derives from the notion that producers will soon be able to use AI to generate original concepts and write screenplays, thereby supplanting the job of the screenwriter altogether. We’re not there yet; “[AI] doesn’t yet extrapolate in the way writers do,” says screenwriter Rachel Bloom. “But it very well could very soon.”

In the interim, writers worry that studios and streamers will be able to deploy AI platforms such as ChatGPT-4 to churn out rough first drafts of scripts using a few simple prompts, and that real human writers will consequently only be brought in on short-term contracts for low pay in order to punch up these AI-generated drafts.

A deal has now been reached between the WGA and the studios, curbing some of the potential uses of AI in the screenwriting process for the time being. Yet AI-fear remains ubiquitous within the screenwriting community and the creative community at large. Actors, novelists, musicians, visual artists, et cetera — one would be hard pressed to argue there is not a fairly widespread sense among creatives that AI could be coming for their jobs in the not too distant future.

Or, if not taking jobs wholesale, augmenting them in deeply disruptive and financially perilous ways, at least as far as the artists themselves are concerned. As Fran Drescher put it during the recent Screen Actors Guild strike, “If we don’t stand tall right now, we are all going to be in trouble. We are all going to be in jeopardy of being replaced by machines.”

How well founded are these intensifying fears around AI, and when we strip back the hype, are we really in a place where the next Paul Thomas Anderson film could just as easily be written (and perhaps even directed) by a chatbot as by the man himself?

Many in the technology and AI spaces certainly seem to think so. “Hollywood is a canary in a coal mine,” said Moran Cerf, Professor of neuroscience and business at New York’s Columbia University, in a recent interview with Canada’s CBC News. “AI will replace the job of the assembly line worker but it will also replace the job of a creative agent who has to come up with a new ad for the Super Bowl.”

Chun Xia, a founding partner of Silicon Valley-based technology investment firm TSVC, believes that TV sitcoms will soon (union deals notwithstanding) be primarily written by AI. As he told the BBC, “AI algorithms will analyse existing scripts, comedic patterns and audience responses to generate content with comedic timing, character dynamics and engaging storylines.”

Credit: Anthony Calvert

In looking at some of the existing technology, one can see why the likes of Cerf and Xia might feel so confident as to the prospects of creative AI. A tool like ChatGPT 4 can be used to churn out a scripted scene in a matter of seconds. I recently prompted it to write me a diner scene featuring a conversation between fictional TV mobster Tony Soprano and comedian Jerry Seinfeld. Here’s just a snippet:

INT. NEW JERSEY DINER — NIGHT

The diner is buzzing with activity and the smell of coffee permeates the air. Jerry Seinfeld sits at a booth, glancing around, as Tony Soprano approaches.

TONY SOPRANO

(to the waitress)

Black coffee, sweetheart. And make it quick.

The waitress nods and heads off. Tony slides into the booth across from Jerry.

JERRY SEINFELD

Tony! How’s it going?

TONY SOPRANO

Eh, you know, same old, same old. The family, the business.

JERRY SEINFELD

The family and the business — sounds like a sitcom.

Tony smirks, nodding appreciatively.

Professor of cinematic arts at USC, Holly Willis, recently ran a similar experiment using GPT. Only in addition to the scene itself, she went further to ask it for a shot list (a breakdown of every camera shot) for her short scene featuring Ken and Barbie. GPT turned one around almost instantly, featuring not only a “montage of fun activities,” but also a “fancy flashback sequence.”

Some Hollywood producers are so impressed by tools like GPT that they are beginning to transition their operations away from human creatives in favour of AI. As CBS reported in mid-2023, OneDoor studios, led by producer John J. Lee, announced that it will rely on platforms including GPT, Adobe Firefly and Jasper.ai to create a crowdsourced film adaptation of Nova McBee’s book series Calculated. According to OneDoor, these tools are already busy at work refining script drafts, generating storyboards and other promotional materials for the upcoming projects.

Credit: Anthony Calvert

For many computer scientists and technologists, AI tools like GPT act as yet another indicator that we are heading toward a future of what’s widely known as Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). As technology journalist Kevin Roose said, “You could probably ask a hundred different AI researchers and they would give you a hundred different definitions of what AGI is.”

But in rankly oversimplified terms, AGI means superhuman machines that surpass us in all areas of cognition, including high-concept reasoning skills and the capacity for originality that one might associate with creativity. Geoffrey Hinton, one of the “Godfathers of deep learning,” told 60 Minutes in 2023 that he is certain we will have AGI in the near future, and that humans will consequently be relegated to the second-smartest entities in the world.

I recently sat down with another revered AGI evangelist to get his take on the coming singularity, and what it’s going to mean for human creatives when it arrives.

Professor Jürgen Schmidhuber is both something of an icon and a pariah within the AI research community. In 2016, The New York Times published an article under the headline, “When A.I. matures it may call Jürgen Schmidhuber ‘Dad’.”

This paternal reputation stems from his work as a pioneer of generative adversarial networks (now widely used in AI systems), artificial curiosity, transformers with linearised self-attention (transformers are at the root of the ChatGPT, and others), and meta-learning machines that, as Schmidhuber puts it, “learn to learn.” He claims that today’s most cited neural networks “all build on work done in his labs.”

His critics say that Schmidhuber has played no small role in bestowing the “Father of AI” title upon himself. He has been accused by other prominent AI researchers, including Yann LeCun, a founder of Facebook’s original neural networks program, of frequently “claiming credit he doesn’t deserve for many, many things.” His manic obsession with recognition, said LeCun in an interview with the Times, “causes him to systematically stand up at the end of every talk and claim credit for what was just presented, generally not in a justified manner.”

Schmidhuber currently spends most of his time at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) on the shores of the Red Sea, where he is still trying to solve the same problem he has been working on since the 1970s. As he describes it, “it’s really about trying to build a machine that can learn by itself and become an increasingly general problem solver such that it becomes much smarter than myself, such that I can retire.”

Our recent video call freewheeled for a few hours on topics ranging from The Rolling Stones (one of his favourite bands), to self-replicating robot factories on Mars, to the colonisation of the entire cosmos within a few tens of billions of years. Where possible, I tried to keep him to the subject of AI as it relates to human creativity.

On that, he is certain of the outcome: Human intelligence will soon be matched, rapidly superseded on every level and ultimately made redundant by machines. In other words, the day “when an AI comes out that is able to quickly produce songs comparable to the thousand best songs in the history of humankind” will soon be at hand. At which point, Schmidhuber says, “history as we know it will draw to a close.” From then on we will be in the hands of our machine overlords.

What makes this a near foregone conclusion, in Schmidhuber’s view, is the fact that human creativity is essentially reducible to a tapestry of predictable patterns. He is dismissive of any notion that there is something inexplicable or lawless about great art, music or literature.

For Schmidhuber, what makes a band like The Rolling Stones special is the way they use existing patterns and then build upon them to create exciting new ones. “Maybe suddenly there’s a minor chord in there when in the past there was no minor chord,” he says. “However it is not a random minor chord there. It is also connected to the rest of the chord structure in a way that is simple. So you have simple ratios between the notes which are participating in the full harmony and the sequence of harmonies, but it’s a pattern that is regular, yet different from the previously used patterns.”

But if human creativity really is “very regular, very compressible stuff,” as Schmidhuber says, then why have AI systems thus far been unable to compress, replicate, and surpass it?

Image Dr. Jürgen Schmidhuber Credit: Supplied

There is of course unprecedented excitement around large language AI models like ChatGPT. Not only can it churn out scripted scenes featuring Jerry Seinfeld and Tony Soprano, it can give seemingly thoughtful and erudite answers to just about any prompt on any subject in a matter of seconds. Still, one would be hard pressed to find a serious computer scientist, neuroscientist, philosopher or author who argues that what GPT does is equivalent to sentience, much less human-level ingenuity.

Noam Chomsky has written that “ChatGPT exhibits something like the banality of evil: plagiarism and apathy and obviation.” In other words, it offers no novel insights, no original style, but is instead only capable of dully recapitulating the human-generated information that it has ingested at eye-watering scale from across the internet.

Even Schmidhuber has to concede that “GPT is essentially just regurgitating the styles of truly creative artists… it doesn’t come up yet with its own, new, unique artistic styles.” Despite the current shortcomings of cutting edge AI systems like GPT, however, Schmidhuber refuses to waiver in his belief that Artificial General Intelligence is imminent. “There are already systems capable of doing things like deriving the principles of arithmetic,” and thereby exhibiting human-level reasoning, says Schmidhuber, “it’s just not GPT.” As for capturing human genius, these systems could still take “months, if not years” to develop, he says. “It will come. We are just in the phase of being scaled up.”

Some other AI researchers are far less confident as to the prospects of AGI. On January 17th, 2023, Grady Booch, a Fellow at IBM who has been described (by esteemed neuroscientist Gary Marcus, no less) as “one of the deepest minds on software development in the history of the field,” posted the following statement on X [formerly Twitter]:

AGI WILL NOT HAPPEN IN YOUR LIFETIME

OR IN THE LIFETIME OF YOUR CHILDREN

OR IN THE LIFETIME OF YOUR CHILDREN’S CHILDREN

As Booch went on to explain to Gary Marcus a few days later, it’s not that he thinks AGI will never happen. Or in his own words: “I will assert that the mind is computable and therefore it is conceivable that synthetic minds can be formed, minds that exhibit the behaviour of organic ones.” The problem, according to Booch, is that the AI industry is by and large on the wrong track. By which he means that most of the money is pouring into large language models like GPT when it could be much better spent elsewhere.

According to Gary Marcus, the industry is still falling prey to what he calls the “scaling-über-alas” narrative. That is, the notion that exponential increases in computing power — and the concomitant power to ingest and process increasingly vast troves of information — will soon lead to a singularity moment, and then alas, we will have AGI. But what’s lacking from this methodology, according to both Booch and Marcus, is any viable sense of cognitive architecture.

We still don’t understand how the human mind really does what it does, at least not as far as higher neocortical functions go — abductive reasoning, complex decision making skills and so forth. Until we have a solid grasp on cognitive architecture, according to Booch, artificial minds are essentially being constructed in abstraction from human ones; they are little more than “approximations of intelligence,” in Gary Marcus’ words. “This is not a problem of scale; this is not a problem of hardware. This is a problem of architecture,” says Booch.

Most current AIs have little-to-no bearing on human cognitive architecture, leaving the two types of entities essentially incompatible. And Booch doesn’t see “anything in the near future of computing that will compress what needs to get AI from where it is today to where it needs to be to form a non-squishy mind.”

Marcus is more optimistic about the chances that we will see AGI some time before the end of the century. But like Booch, he thinks that a lot of the focus and money is currently flowing in the wrong direction. “I think a lot of core problems from seventy-five years ago are still unsolved,” he says. “[American computer scientist] John McCarthy worried about common sense in 1959, and I still don’t see a solution I can take all that seriously.”

Another major issue, as both Booch and Marcus see it, is that the field of AI is bursting at the seams with hubristic computer scientists who summarily disregard perspectives from other domains. “We as computer scientists not only vastly overestimate our abilities to create an AGI,” says Booch, “We vastly underestimate and underrepresent what behavioural scientists, psychologists, cognitive scientists, neurologists, social scientists, and even the poets, philosophers and storytellers of the world know about what it means to be human.”

Perhaps Schmidhuber somewhat proves their point here in summarily declaring that some of the most resonant popular music of the last sixty years is made of “very simple, very compressible stuff.” Before going on to try to explain songwriting and musical dynamics in startlingly simplistic terms, all while never having composed a single recognisable song of his own.

Credit: Anthony Calvert

So how close are tools like ChatGPT to putting the artists out of work? As a critic opining from the sidelines, perhaps the only viable metric we have to go on here are the tools themselves. In other words, how good are they really at writing?

In briefly trying to answer this question, let’s consider my Soprano/Seinfeld scene. “So, Seinfeld, what’s the deal with your obsession with cereal? I hear you’ve got a whole cabinet dedicated to it,” says Tony at one point. To which Jerry responds: “Cereal is the breakfast of champions, Tony. It’s simple, no-nonsense. Like a good mob operation.” It’s all like this, basically; which is to say the scene is hollow and contrived from start to finish. On top of the fact that it has zero in the way of stakes or conflict, at no point do the characters have any sort of motivation, perspective, moral compass or intelligence. They interact with one another to a point, which puts them at a slight remove from, say, a Buzz Lightyear doll — push his button and he delivers one of his most iconic catchphrases from a randomised carousel. But it’s not much of a remove.

In this light, does it feel like our cold AI tools are getting warmer to you?

This article features in the March 2024 issue of Rolling Stone AU/NZ. If you’re eager to get your hands on it, then now is the time to sign up for a subscription.

Whether you’re a fan of music, you’re a supporter of the local music scene, or you enjoy the thrill of print and long form journalism, then Rolling Stone AU/NZ is exactly what you need. Click the link below for more information regarding a magazine subscription.