The 20 Most Iconic Aotearoa Music Moments Of All Time

What are the most iconic Aotearoa music moments of all time?

Like a scene from your favourite film, a single song can soundtrack the best (and worst) moments in our lives. It’s these tunes that transport us back in time, often without warning as they appear on playlists or in the background of a TV ad, triggering locked-away memories from years gone by.

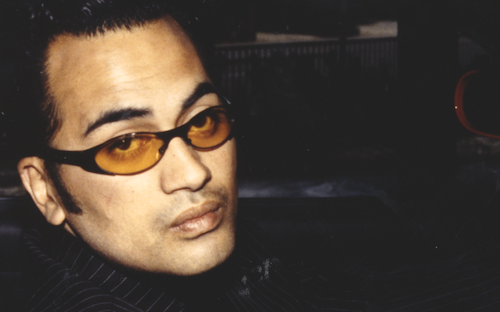

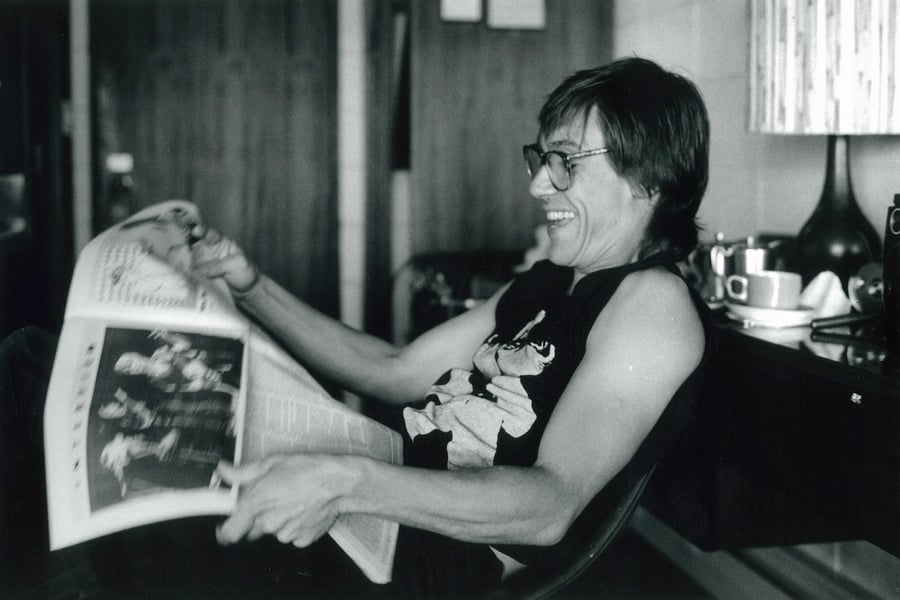

Music also soundtracks some of the greatest, and most iconic, moments in popular culture. As do the remarkable Aotearoa music artists behind the music, who themselves are responsible for many decade-defining moments that appear throughout this Rolling Stone list.

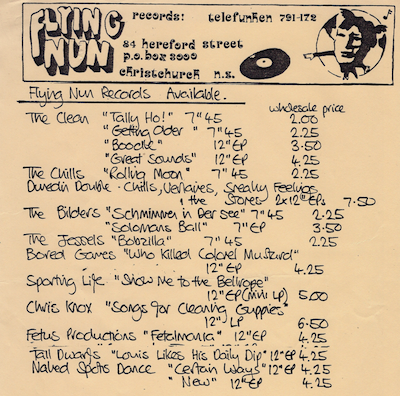

Think about the rise and rise of homegrown stars like Lorde, the cultural impact of upstart record labels like Flying Nun, and the infiltration of music television into popular culture and public consciousness. Iconic music moments are everywhere.

A moment in time married with music can break down barriers, ignite movements, start trends, launch industries, give birth to icons, and change the course of history — for good. Some of the trailblazing people that appear on the Rolling Stone List — including Pixie Williams — have achieved all of the above. It’s the stuff of legend, and the making of legends.