Rush’s Neil Peart: 12 Essential Songs

From “2112” to “Tom Sawyer,” we look back at some of the legendary drummer-lyricist’s high-tech highlights

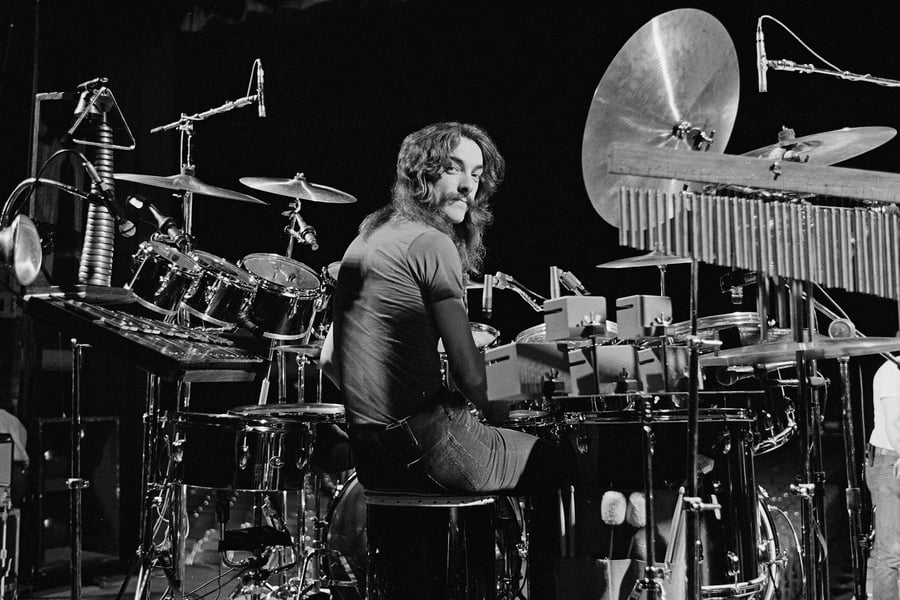

Fin Costello/Redferns/Getty Images

“Neil Peart, that’s a whole other animal, another species of drummer,” Dave Grohl told Rolling Stone in 2018, responding to a question about whether he could ever sit behind the kit for Rush. It’s a sentiment pretty much unanimously agreed upon in the rock world: Peart’s feats on his instrument, the way he powered Rush’s brain-bending songs for 40 years, with a combination of jaw-dropping technicality and artful eccentricity, did make him seem downright superhuman. Add in his lyrical gifts, which fueled both the band’s conceptual prog-era epics and its heartfelt hits in the Eighties and beyond, and you have a polymathic talent with no real peers in his field.

It would take dozens of tracks to represent the full scope of Neil Peart’s genius as a percussionist and wordsmith, but consider these 12 — which stretch from the first Rush album he appeared on in 1975 to the trio’s final LP close to four decades later — as an invitation into the wider world of the man they called the Professor.