Rufus Wainwright: My Life in 15 Songs

The singer-songwriter looks back at his life in music, from “Foolish Love” and “Poses” through his inspired new album, Unfollow the Rules

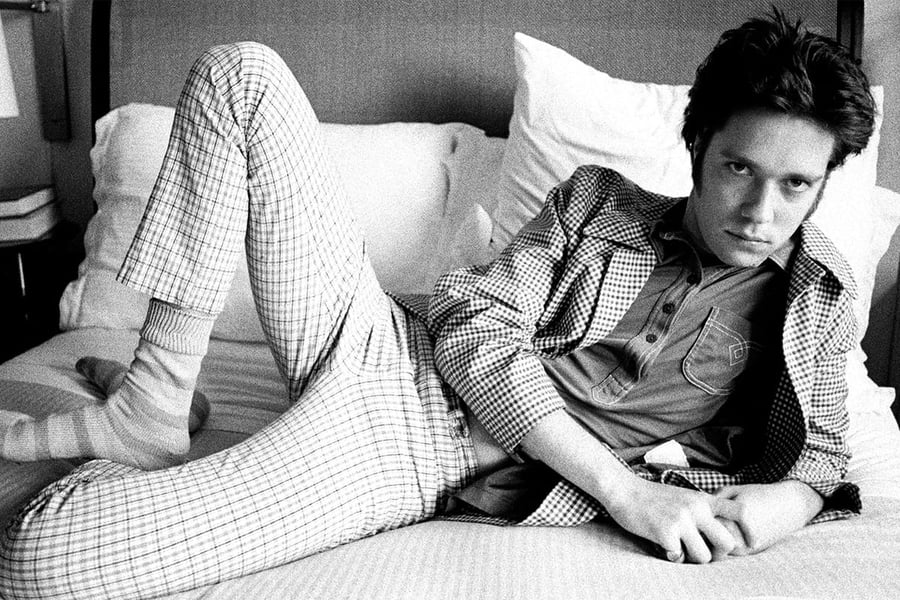

Catherine McGann/Getty Images

Two years ago, when Rufus Wainwright celebrated the 20th anniversary of his debut with a series of tour-de-force concerts, performing the songs that kicked off his career helped him tap into a new creative wellspring. “In order to progress, at this point in my life, it’s good to take stock,” says Wainwright, 46. “See what worked, what didn’t, and how to move forward.”

That self-interrogation ended up yielding Unfollow the Rules, Wainwright’s inspired new album. Recorded in Los Angeles with producer Mitchell Froom, it’s Wainwright’s first unabashedly pop LP since 2012’s Out of the Game, and a reminder of how much fun he can have with a sky-high chorus and a full studio sound. He made the album last year, and it arrives at last on July 10th, after a three-month delay due to the COVID-19 shutdown. (Wainwright used the time off well, performing a series of intimate home concerts in L.A. for his own Instagram followers and for Rolling Stone’s “In My Room.”)

Before the pandemic hit, he came by Rolling Stone’s New York office to reflect on his life in music, as seen through a selection of his greatest songs. “We’re here today to peruse my artistic output,” he says, “and figure out what’s behind the parade.”

Taken together, these songs tell a story with enough drama and beauty for one of Wainwright’s beloved operas. They range from early conflicts with his two singer-songwriter parents, Kate McGarrigle and Loudon Wainwright III (who divorced when Rufus was three); through his own years as a downtown NYC star; through addiction, recovery, and profound loss; up to his present contentment with a marriage and family of his own. Through the years, he’s written songs about all the highs and lows, without ever pulling punches or playing down personal disappointments.

“That’s something I grew up with quite intensely,” Wainwright says of his autobiographical style. “I’d go to my mom’s shows and she’d sing a song about my dad, or vice versa, or a song about me or my sister. They were all imbued with love, all caring songs. Occasionally there were some cheap shots, but mostly they’re very heartfelt homages. It was a circular firing squad of beautiful music.”

Here are 15 of his sharpest shots.