Merle Haggard: 30 Essential Songs

From the defiance of “The Fightin’ Side of Me” to the melancholy of “If We Make It Through December”.

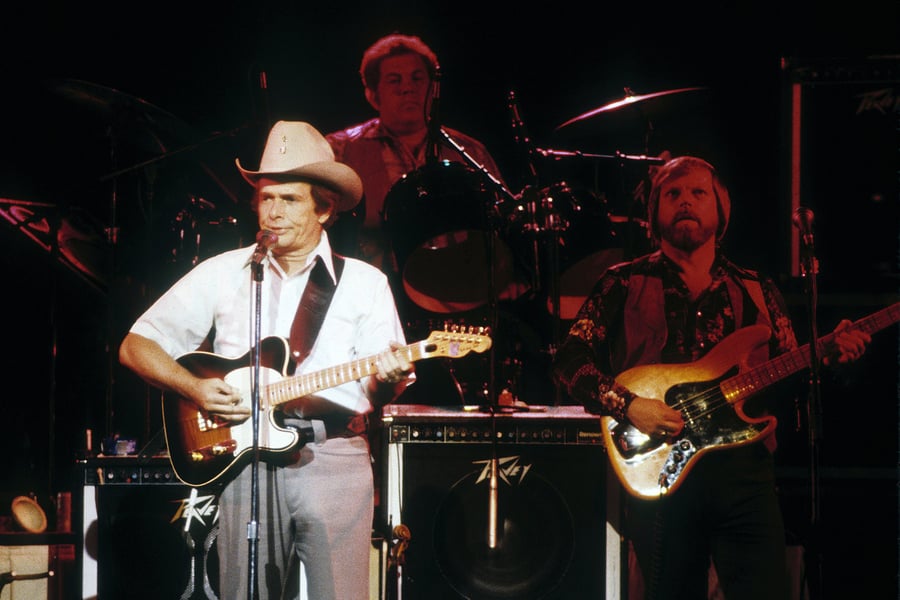

Merle Haggard's drummer Biff Adam, shown here onstage in 1979, has died at 83.

Larry Hulst/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

One of his many nicknames was the “Okie From Muskogee,” taken from his song of that title that became a conservative anthem during the Vietnam War. But “conservative” was never the way to describe the country music phenomenon that was Merle Haggard. A pioneer of both the Bakersfield sound and the Outlaw Country movement, the California native and one-time resident of San Quentin Prison was a rule breaker both in and out of the studio, developing a sound that has been emulated by countless artists since who’ve walked in — and worshiped — his bootsteps. Presented in chronological order, here are the 30 songs, from the rebellious to the romantic, that collectively reflect the greatness of Merle Haggard’s 54-year career.

Related: Merie Haggard, Country Legend, Dead at 79

Compiled by Patrick Doyle, Jon Freeman, Joseph Hudak, Erin Manning, David Menconi, Marissa R. Moss, Mick Murry, James Reed and Sarah Rodman.

“The Bottle Let Me Down” (1966)

This 1966 weeper is one of Haggard’s stone-cold classics, and perhaps among the best musical encapsulations of how it feels when self-medication fails. Sitting at the bar trying to drown his demons, the singer finds the memory of an old love intruding no matter how much he imbibes. Female background vocals enter, sounding almost like the former flame haunting and taunting him as he tries to drink her off his mind. Oft-covered — from Elvis Costello to the Mavericks to Emmylou Harris — but never bettered, the bottle itself may have failed the narrator but “The Bottle” has gone on to do the trick for countless jilted lovers. S.R.

“Swinging Doors” (1966)

It’s the song that makes you revere Merle Haggard as a honky-tonk hero and pity the poor women who had to put up with his hard living. Life doesn’t get much better than the one Haggard laid out in “Swinging Doors.” He’s got it all, from a jukebox to a barstool to a flashing neon sign. “Stop by and see me anytime you want to/ ‘Cause I’m always here at home till closing time,” he sang. “And thanks to you I’m always here,” he added, essentially lifting a middle finger to his beloved. But you also suspected he was one wisecrack — or drink — away from a meltdown. J.R.

“Sing Me Back Home” (1967)

In “Hungry Eyes” and “Roots of My Raising,” Haggard’s narrators use music to revive memories they’ve been holding since childhood. “Sing Me Back Home” is a song about a prison inmate who does the same for someone else, strumming a tune for a fellow convict who wants to hear his old favorite as he walks to his death. It’s a dramatic moment, but Haggard doesn’t sing it like one: His dry, dignified voice suggests not a performer on a stage but a hardened stoic replaying one of his life’s most harrowing moments. The song is fiction, its narrative recalling the 1965 hit “Green, Green Grass of Home,” but basing its details on “a conglomeration of information” that stuck with him from his own days in San Quentin. N.M.

“I’m a Lonesome Fugitive” (1967)

It would be easy to assume that Haggard wrote this song about a fugitive running from the law, but credits actually go to Liz and Casey Anderson, who crafted a rich story loaded with metaphor and references to everything from Rudyard Kipling to Bob Dylan. Apparently, the Andersons weren’t aware of Haggard’s sordid past, and even the Hag himself was awestruck at how well the song resonated with his own personal history — which helped him slink perfectly into the midtempo western shuffle that not only speaks of his past, but his present too. “I’m on the run, the highway is my home,” are as much the words of a highway-dwelling musician as a criminal on the lam. M.M.

“Mama Tried” (1968)

Released in July 1968, “Mama Tried” was Merle Haggard’s fifth Number One song and is synonymous with the country singer, who was inspired to write the tune by the suffering he caused his own mother while incarcerated in San Quentin State Prison in 1957. With Roy Nichols on electric guitar and Haggard’s early life influences, the classic breaks free from Nashville country, opting for 1960s California honky-tonk that embodied the Bakersfield Sound Haggard was known for. It has remained a timeless live standard for country bands of every shape and color, famously covered by the Grateful Dead, the Everly Brothers, Reba McEntire and Willie Nelson. Even for those who haven’t robbed a roadhouse or spent any time in the slammer, quoting the lyrics from “Mama Tried” serves as a personal summation of one’s badassery. E.M.

“Today I Started Loving You Again” (1968)

Around 2 a.m. one night in Dallas in 1967, Merle Haggard asked his wife Bonnie Owens if she could go down the street to get him a hamburger. When she returned to their motel room, he had written “Today I Started Loving You Again.” “It’s amazing to me the things that come out of Merle’s mouth when he’s writing,” Owens said in Nicholas Dawidoff’s Country of Country: A Journey to the Roots of American Music. “I never heard him talk like that. He’d say later, ‘Bonnie, I don’t ever remember saying those words. It’s like God put ’em through me. I knew he said them — I was there. I’d write them down.” Released in 1968 as the B-Side to “The Legend of Bonnie & Clyde,” it didn’t make the country Top Ten until Sammi Smith released her cover in 1975, and it’s echoed out of country bars ever since. P.D.

“The Legend of Bonnie and Clyde” (1968)

A year after Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty immortalized Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow on screen, Haggard condensed the love story and notorious demise of the 1930s outlaws into two minutes of pickin’ and grinnin’ bluegrass. (Fun fact: that’s Glen Campbell tearing it up on banjo.) Bonnie Owens, Haggard’s wife at the time, sang backup and co-wrote the song, which was the title track of Haggard’s 1968 album with the Strangers. Despite lyrics about robbing and killing, Haggard seemed downright wistful about the deadly duo: “But we’ll always remember how they lived and died.” J.R.

“Silver Wings” (1969)

Look around the room when Haggard sings this live, and the same scene unfolds: Someone is inevitably wiping away tears. From 1969’s A Portrait of Merle Haggard, “Silver Wings” wasn’t a Number One hit but has endured as one of his greatest heartbreakers, on par with Mickey Newbury at his most mournful. Romanticizing an airplane’s “silver wings” that take away his lover, Haggard sang so intimately that you wondered if you were eavesdropping. Even the arrangement — with its slack guitar strums, soft brushes on the drums and a majestic wash of strings — felt like a sucker punch to the gut. Pass the Kleenex. J.R.

“Workin’ Man Blues” (1969)

Ushered in with bits of funky guitar, 1969’s “Workin’ Man Blues” became an anthem for the bluesy, blue-collar Bakersfield Sound that Haggard would come to personify. And those quirky intro licks would emerge as downright iconic too, making it increasingly safe for traditional country crooners to play as much in rock & roll waters as they damn well pleased. When the track was released, Haggard was having anything but the blues — he’d been riding high after seven Number One songs, but he refused to forget the rough and tumble roots that birthed him, singing the anthem of a man with nine children, struggling to get by. Years later, Bob Dylan would write his own riff on the song, “Workingman Blues #2,” after touring with Haggard — godlike figures of music, still pondering the common man. M.M.

“Hungry Eyes” (1969)

Also known as “Mama’s Hungry Eyes,” this tribute to the man’s own single mama was the high point of his 1969 album A Portrait of Merle Haggard. And it’s a masterpiece of unusually sophisticated empathy, evoking soul starvation that’s every bit as oppressive as hunger of the stomach. The hardscrabble setting is a Depression-era labor camp, and the whole thing is all the more heartbreaking because the singer admits he had no idea how much pain his parents were in. It’s only in retrospect that he realizes what was going on, recalling struggles that only led to “a little loss of courage as their age began to show” and more sadness in those titular hungry eyes. D.M.

“Okie From Muskogee” (1969)

Was he being sincere or satirical? Probably a bit of both. One of the Hag’s most misunderstood songs, written with Strangers drummer Roy Edward Burris, “Okie From Muskogee” has been endlessly debated since its release at the height of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. Set to pastoral acoustic guitar and featuring some of his most reverent vocals, it waxed romantic about the values of small-town America, where “we don’t let our hair grow long and shaggy/like the hippies out in San Francisco do.” (Given his open fondness for it now, his anti-marijuana stance is pretty comical in hindsight.) Haggard has said the anthem was his salute to the troops, and he still ends most of his concerts with it. J.R.

“White Line Fever” (1969)

Don’t let the title mislead you, this stripped-back track — which appeared on the watershed live Okie From Muskogee album — isn’t about that demon cocaine but rather the white lines of the highway and the allure and the monotony of the folks who are driven to choose that path. The narrator could be a long-haul trucker, a restless nomad or a weary country superstar looking out at the road rushing under his wheels, the steady tempo and elongated croon mirroring the mesmerising view of the lines flying by on the pavement. Haggard was often drawn to themes of aging and mortality as a writer and here he was only in his early thirties when he sang “The wrinkles in my forehead/Show the miles I’ve put behind me/They continue to remind how fast I’m growin’ old/Guess I’ll die with this fever in my soul.” S.R.

“The Fightin’ Side of Me” (1970)

Just four months after “Okie From Muskogee” established Haggard as spokesman for small-town conservative America, he doubled down with this love-it-or-leave-it challenge to those who were “harpin’ on the wars we fight an’ gripin’ bout the way things ought to be.” And just like “Okie,” “The Fightin’ Side of Me” shot straight to Number One on the country charts. The chuckle in his tone suggests Haggard is a man who enjoys a barroom tussle every now and then. But even in the midst of a call to arms this blatant, Haggard is smart enough to see the dissenting viewpoint: “An’ I don’t mind ’em switchin’ sides/An’ standin’ up for things they believe in.” Just don’t go, as he warns, runnin’ down his country, man. D.M.

“If We Make It Through December” (1973)

This wistful ode to escaping to a warmer climate, and perhaps a better life, was one of Haggard’s biggest hits and a popular cover choice for everyone from Alan Jackson to Joey + Rory. Although it is not a Christmas song, per se — it was originally released on his album Christmas Present and revived years later for his seasonal outing with Willie Nelson, Pancho, Lefty and Rudolph — it does reference the holiday as a father apologizes to his daughter that there will be no presents or trimmings. Why? Daddy got laid off down at the factory. Perhaps the incongruously peppy tempo is the narrator’s way of convincing his daughter, and himself, that if they make it through this cruel month they will indeed be fine. S.R.

“Things Aren’t Funny Anymore” (1974)

In addition to being Haggard’s 17th Number One on the country charts, “Things Aren’t Funny Anymore,” released in February 1974, showcased the rough-hewn singer’s softer side. Using his unraveling second marriage to Bonnie Owens as source material, Haggard really lets the hurt come through when he belts: “Seems we’ve lost the way to find all the good times we found before/Yeah, we used to laugh a lot/Things aren’t funny anymore.” Twin fiddles play the instrumental break like a broken heart pining over love’s uncertainties in a tale as old as time — one that appealed to fans beyond Haggard’s blue-collar country audience. E.M.

“Holding Things Together” (1974)

Haggard has tackled many unusual subjects over the course of his career, and the tender, nearly heartbreaking “Holding Things Together” is one of his best moments dabbling in life’s lesser-told stories. This tale of a man raising his children in the absence of a runaway wife isn’t something often spoken about in country music, but Haggard delivers it with stunning honesty. “The postman brought a present, I mailed some days ago,” he sings. “I just signed it ‘love from mama,’ so Angie wouldn’t know.” In a genre often mired in machismo, this image of a single father making uneasy attempts at the role of mother, too, is as rare as it is devastating. Dwight Yoakam realised the song’s power, exposing it to a much larger audience on a 1994 Haggard tribute LP. M.M.

“Ramblin’ Fever” (1977)

By the late 1970s, the pace of Haggard’s songwriting had slowed to a trickle. He wrote only two songs on 1977’s Ramblin’ Fever (his MCA Records debut after an enormously successful 12-year run at Capitol), but he made them count – especially the title track, which stands among his greatest works. “Ramblin’ Fever” swaggers out of the gate with the declaration, “My hat don’t hang on the same nail too long.” But as usual with Haggard, there’s always ambivalence if you listen closely, past the beer-soaked bravado and hot picking. A verse later he’s declaring, “If someone said I ever gave a damn, they damn sure told you wrong” with just enough quaver to make it clear that he does in fact care. It ain’t easy being Merle. D.M.

“Driftwood” (1979)

The song from 1990’s Blue Jungle that earned the most attention was probably “Me and My Crippled Soldiers,” a political track that voiced the singer’s displeasure with a Supreme Court decision protecting flag-burning as free speech: “Might as well burn the Bill of Rights as well/And let our country go straight to hell.” But a message record has to sound memorable, and that one didn’t. In contrast, “Driftwood,” which was blithely uninterested in politics, stays with the listener. Haggard grabs the attention immediately by holding each of the syllables in the title phrase for an unnaturally long amount of time. Hand percussion, an unusual texture in country music, flutters next to the thumping kick drum, and the guitar inserts itself with precision around the big, round bass notes. “Driftwood” is one of the most passive leaving songs in Haggard’s catalog, which is well stocked with songs about walking away. Here he just shrugs his shoulders and floats on to the next stop: “I can’t always be here with you, baby/ I’m just driftwood drifting by.” E.L.

“Footlights” (1979)

By the end of the Seventies, Haggard had spent nearly half his 41 years playing music professionally (or at least semi-professionally) and was feeling some wear and tear. For his album Serving 190 Proof, he wrote the song “Footlights” about a musician who doesn’t always enjoy being onstage the way he used to but doesn’t really have a backup plan. Instead, he puts on his game face and tries to “kick the footlights out again,” to ensure the people get their money’s worth. It’s hard not to wonder how tough it was for Haggard to do the same thing 40 years later. J.F.

“Misery and Gin” (1980)

Haggard was nearing the end of a brief and tumultuous marriage to third wife Leona Williams when he recorded Back to the Barrooms, including the rousing “I Think I’ll Just Stay Here and Drink.” He kicked off the album with John Robert Durrill and Snuff Garrett’ “Misery and Gin,” a heartbreaking ballad that David Cantwell wrote in Merle Haggard: The Running Kind “cultivated a Tin Pan Alley classicism that suited Haggard’s mature voice and phrasing.” Haggard scored a Number Three hit with it in 1980. After Barrooms, Haggard took up residency on a houseboat on Lake Shasta during his hardest-living period. Haggard’s band the Strangers sat out the session, with producer Jimmy Bowen instead bringing in a band that perfectly replicated their sound. “Merle brought the [Strangers] in, and old Roy Nichols, his guitar player, sitting on the couch, listening to the playback,” said Bowen. “He turned to one of the other guys and said, ‘Damn, I don’t remember us doing that.’ He thought it was him!” P.D.

“I Think I’ll Just Stay Here and Drink” (1980)

Thirty-one albums deep and nearly 15 years after the release of swill-em-back classics like “The Bottle Let Me Down,” Haggard went Back to the Barroms in 1980 to remind the emerging Countrypolitan crooners that the genre really belongs in a honky-tonk, not in the hands of a shimmery orchestra. “Ain’t no woman gonna change the way I think,” Haggard sings is his classic baritone, his syllables elongated by just enough shots of bourbon — ain’t no one, actually, going to change the way the Hag thinks or sings, and this was proof. Even though it clocked in at over four minutes and allowed for ample, loose instrumental grooves (thanks in particular to Reggie Young’s nimble guitar and Don Markham’s wail on the sax), it still went to Number One. Nobody made their own rules like Haggard, and no one was so content to break their own, either. M.M.

“Are the Good Times Really Over (I Wish a Buck Was Still Silver)” (1982)

Haggard returned to the down-home values of “Okie From Muskogee” for this state-of-the-union ballad, which was named Song of the Year by the Academy of Country Music in 1982. In a way, it’s the Hag’s “get off my lawn” song, replete with gripes about lying presidents, the longevity of American-made cars and those newfangled microwave ovens — he’d win no points with feminists when he pined for a “girl who could still cook, still would.” Just as outrageous was the later pro-pot Haggard’s line about wishing a joint was still a “bad place to be.” Ultimately, though, the then 45-year-old comes across as more cautionary sage than grumpy old man, warning about a U.S. that is headed straight to hell. It was a sentiment shared by gloom-and-doom politicians and talk-show hosts alike — late loudmouth Morton Downey Jr. would even cover the song. J.H.

“Big City” (1982)

After a rough two days of recording 23 songs in 48 hours (in the midst of 1981’s scorching hot July), Haggard’s band was packing up when he went outside to check on his best friend and bus driver, Dean Holloway. Peeved by the heat and grueling schedule, Holloway actually uttered the phrase, “I’m tired of this dirty old city,” inspiring the country man to run back inside and take Holloway’s anger out on paper with the rest of the band. Thanks to Holloway’s inspiring words, the Hag rolled out of Los Angeles with a song tapped into urban frustrations that still resonate with Americans today — an escapist dream to move “somewhere in the middle of Montana.” (Maybe that’s where John Mayer got the idea to flee from his troubles and relocate to Big Sky Country in 2011.) Regardless, the title track to Big City became Haggard’s 27th Number One single on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart in April of ’82. E.M.

“That’s the Way Love Goes” (1983)

A lifelong admirer of Lefty Frizzell, Haggard paid homage with this cover of Frizzell’s “That’s the Way Love Goes,” which became the title track of a 1983 album. (He also dusted it off in 1999 as a duet with Jewel.) Johnny Rodriguez first took it to the top of the charts in 1973, and Connie Smith and Willie Nelson also recorded memorable versions. Haggard’s take, even with electric piano adding some Eighties gloss, stayed true to the original’s tenderness — a celebration of lasting love and the peace of mind it brings. J.R.

“Pancho & Lefty” (1983)

Even when he wasn’t writing, Haggard knew a good song when he heard one and wanted to make sure that more people knew of the masterworks of Townes Van Zandt when he partnered up with pal Willie Nelson for their 1983 duet record Pancho & Lefty. The title track, originally released by Van Zandt in 1972 and introduced to the Hag by his daughter, may have reached cult status among a small fan base and certainly fellow artists, but Van Zandt never dreamed it would see the country charts, which it did when Haggard and Nelson’s cover shot right to the top. Though “Pancho” is about a bandit on the run — maybe or maybe not Mexican general Pancho Villa — the dynamite duo turned it into a parable for the outlaw life, on the road not from the law but the banalities of a traditional existence, where most nights are spent on the couch, not on stage. M.M.

“Kern River” (1985)

If Ray Price gave us “Heartaches by the Number,” “Kern River” is heartbreak by geography: South San Joaquin, “where the seeds of the Dust Bowl began”; the hills of Lake Shasta, where our defeated narrator lives in exile; and of course the river of the title, the border between Haggard’s Oildale and Buck Owens’ Bakersfield, the place where the old man first fell in love then lost his love to a powerful current. Haggard neglects to include much detail, but what he allows gives each location the weight of symbolism. When he concludes that he’ll never again swim the Kern, he’s really steeling himself for more years of sad songs and loneliness. N.M.

“If I Could Only Fly” (1987)

Albums from this period of the Hag’s recording career aren’t usually his most lauded, and 2000’s If I Could Only Fly is one of them, released via the hip Epitaph imprint Anti-, now how to such quirky acts as Man Man and the Milk Carton Kids. It’s a shame, because songs like the title track reaffirm that not only was Haggard as influential as they come in shaping country music, he was often a subtle, stirring wordsmith too. It’s a weeping folk ballad accompanied by simple, sentimental guitar and Haggard’s voice, beautifully frayed from age, singing of a romance with miles and miles between two lovers: “if we could only fly/there’d be no more lonely nights.” Underneath it all is the tearful unspoken reality — the distance isn’t the problem, it’s just that he’s a man built to roam. M.M.

“No Time to Cry” (1996)

Buried on one Haggard’s lesser-known albums 1996 (the follow-up to 1994) was one of his most heartbreaking performances, a cover of Iris DeMent’s ballad about coping with the loss of a parent and getting older. Haggard met directly with DeMent to learn the song. Nicholas Dawidoff’s In the Country of Countrydetailed the session, in which Haggard gave a window into his hard-won process of masterfully interpreting songs: “I’m trying to decide how to sing this,” he said. “It’s not really sorrow. It’s a kind of emptiness that comes on when you know the dearly departed are really gone. It’s real hard to describe it without being morbid or unpleasing. Some songs, great songs, you can’t bear to hear them because they make you cry.” P.D.

“Wishing All These Old Things Were New” (2000)

The Nineties were a fallow period for Haggard, at least from an artistic standpoint. After three albums on Curb Records, he signed to the hip Los Angeles label Anti- and returned to form on 2000’s If I Could Only Fly. (Upon release, Haggard quipped, “I’m giving it a higher score than any album I’ve made to date, but what the hell do I know?”) The opening track “Wishing All These Old Things Were New” set the tone for his latest tales of redemption, wasting no time in cutting close to the bone: “Watching while some old friends do a line/holding back the want to in my own addicted mind.” J.R.

“Live This Long” (2015)

This gem penned by Shawn Camp and Marv Green comes from the Hag’s superb 2015 duets album with Willie Nelson, Django and Jimmie. The two old lions sit around the pride, roaring about their gloriously misspent youths alluding to the ladies they loved, the songs they sang and the friends they lost along the way. But there is real pensiveness to the chorus, in which they intone, “We would’ve taken much better care of ourselves/if we’d known we was gonna live this long.” In light of the health concerns Haggard faced later in life, this wry twilight reflection takes on new poignance as he speak-sings with sincerity to Nelson, “Well we’re in pretty good shape, Will, for the shape we’re in and we’ll keep rocking along til we’re gone.” S.R.