Photo by Pier Carthew

Women of a certain age are now finding the confidence to talk about the darker side of entertainment.

Women of a certain age are now finding the confidence to talk about the darker side of entertainment.

When music journalist Jane Gazzo was researching for her latest book celebrating the fertile Australian music scene of the 1990s, it quickly became apparent that many female artists were remembering the time with a heavy heart.

For every Adalita and Sarah McLeod whose careers have transcended the 1990s, there were also the women who either by fault or default became casualties of the decade; who lacked the confidence and wisdom to speak up about what was going on around them and for whom support networks and mental health awareness was virtually non-existent.

For these women, the Nineties were about promising careers cut short, media cruelty, industry bullying, misogyny and double standards. They are now collectively finding their voices and breaking over twenty years of silence.

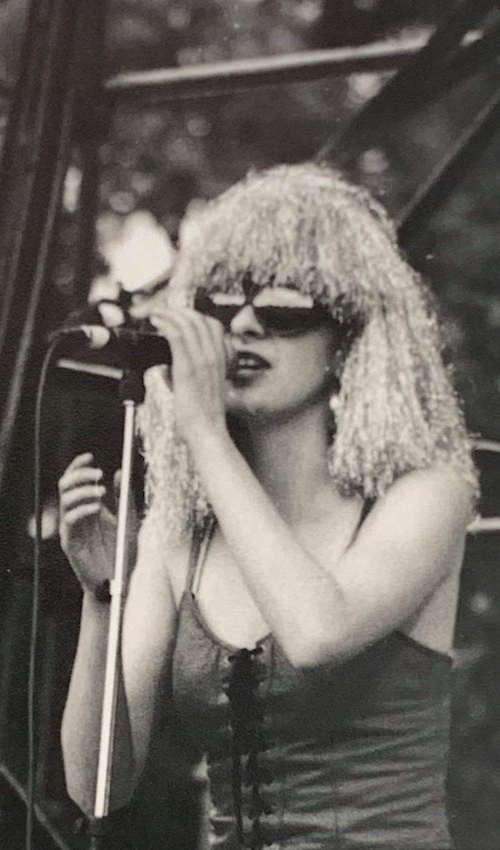

Singer Caroline Kennedy was in her late twenties when she fronted Melbourne band Deadstar with former Hunters and Collectors guitarist Barry Palmer in 1995. Also in the group was drummer Peter Jones, who had replaced Paul Hester in Crowded House, as well as Crowded House bassist Nick Seymour.

Before Deadstar, Kennedy had fronted various indie rock bands and had enjoyed a degree of success with The Plums. But according to Kennedy, the media, and her management, seemed only interested in the high profile names attached to Deadstar.

“I was shamelessly worked like a donkey in a pit,” she says matter-of-factly. “But I was also very lucky. It was a mixed blessing to be working with a bunch of older men who were already well known in Australian mainstream music circles.”

Kennedy also discovered that being a frontwoman in a band in the late Nineties was open slather for snide music journalists to criticise everything about her — from her voice, to her looks and dress-sense.

“I was abused by lots of different people when I transitioned from The Plums to Deadstar,” she states. “I did photo shoots where people told me my tits weren’t big enough and they brought me a pair of tits in a box! I had that kind of thing happen to me frequently.”

Caroline Kennedy. Photograph by Stephen Guille

Kennedy found that standing up for herself and saying no to certain requests could paint her into a corner.

“I definitely got a reputation for being a difficult woman,” she admits. “I couldn’t fit easily into those clichés of decorative femininity. I’m not that kind of person and I never was.”

When a Deadstar retrospective greatest hits collection CD was released without warning and with a photo of Kennedy which she hadn’t approved, she baulked and had it pulled from the shelves.

“I was so angry, but I felt like I was being treated as an accessory.”

Kennedy is proud of the body of work Deadstar produced over their six-year period, which included three albums and three ARIA nominations. Although emotional when revisiting her former band, she is far from jaded, using her experiences to empower the young female musicians she currently teaches at London’s Goldsmith University.

She has been recording as a prolific solo artist under the moniker Caroline No since 2012 — a name chosen for the fact she didn’t say no often enough during those Deadstar years.

So is it the passing of time, and the fact that she is older, wiser and surer of herself, that has given her the strength to speak up now, or is it that the culture has shifted just enough to allow her a voice?

She ponders the question.

“Experience has shown me that what I thought was ‘just how things are’ was in fact a construct. I know now that I have many more choices than I could ever have imagined when I was younger. When any of us speak about injustice, we create a space for everybody.”

Meanwhile, on the opposite side of the musical spectrum, pop starlet Melissa Tkautz was just seventeen-years-old when she topped the ARIA charts with her debut single, “Read My Lips” in 1991. It earned a Platinum record and an ARIA for highest-selling single in 1992. Her follow-up single, “Sexy is the Word”, went Gold, peaking at number three.

At the same time Tkautz was playing the rebellious Nikki Spencer on TV drama E Street and the soap’s producers were keen to capitalise on her popularity. However, Tkautz believes that her age and naivety often resulted in the men around her taking advantage of her.

“I was never touched inappropriately, which I’m grateful for,” she affirms. “And there were a lot of situations where I could have been; but I was in the care of men who either ripped me off or had a complete lack of respect for me as a young girl starting out in the music industry. They were the ones letting me down. I would say I was abused mentally.”

Pop starlet Melissa Tkautz found it difficult to overcome her trust in men after being taken advantage of in her formative career years. Photograph by Gerrie Misfud.

Tkautz alleges that the men who ripped her off were the three managers who had come highly recommended by her record company, although no legal action was ever pursued. She is also keen to clarify that former managers Richard Wilkins and Penny Clifford were not part of this three, and speaks highly of both.

“I trusted the managers who I had in my family home, sitting at my dinner table, who were ripping me off blind behind my back.”

“I trusted the managers who I had in my family home, sitting at my dinner table, who were ripping me off blind behind my back. They were taking money out of my account, spending money on things which had nothing to do with me or my career. If I had found the manager I have now, the journey would have been a lot different for me and certainly a lot more enjoyable.”

There was also the obsession from the media and those around her about how she looked. She was constantly told she was too fat, or too thin, and her weight spiralled.

“Then my boobs weren’t big enough. Or they weren’t perky enough. It was just insult after insult. The more famous I got, the more judgements I got.”

Tkautz becomes emotional when recounting a particular experience involving a record producer who made her watch her own video clip to “Read My Lips”.

“He sat me down and he said, ‘Right, see how you look in this film clip? We need you to look like that right now in everyday life’. He was basically saying I looked shit and I needed to look how I looked in that video with my hair and make-up done all the time — forgetting of course that we had the best stylists and make-up artists on set and lighting. Imagine being seventeen and just coming into your body? It destroyed my confidence. I felt like the ugliest person in the world and my sense of self was so warped.”

It’s clear the experience is still upsetting. The passing of time has healed only so much. Therapy has also helped, but the thing Tkautz found most difficult to overcome was her trust in men. She was celibate for ten years whilst she worked through her trauma.

“I could not let a man in for the longest time because I was so scared they were going to tell me something about myself that was negative, and I couldn’t go there. I’d been put down for so long,” she says. “Sex was not something I was comfortable with at all.”

The irony of singing her hit single “Sexy is the Word”, when she was feeling anything but, is not lost on Melissa now.

“I was singing ‘Sexy’ and the line ‘hands off my detonator’ but mentally, I hadn’t developed into the sexual being they were wanting me to portray in those songs. I hadn’t found myself until I was in my twenties and I think that’s where the problem lies. I developed at a very late age. I wasn’t sexually active and I had very little life experience.”

Today Melissa is a happily married mum of two, still performing and writing music while working on a number of acting projects. There is a deep sense of gratitude for the longevity of her career, which she mentions numerous times. While she may have the confidence to speak of the past, she believes, given the chance again, she would do things very differently.

“I would have protected myself a bit better and not been so trustworthy. I would have had more of a say, and if anyone had of passed judgement on what I looked like I would have told them to go fuck themselves.”

Tania Lacy was an aspiring comedian and television presenter who shot to fame hosting the revamped Countdown Revolution on ABC TV from 1989-1990.

She had cut her comedic teeth on the network’s Saturday morning show The Factory, where she would invent amusing characters and hilariously interview artists in different personas. ABC executives were quick to spot her talents and capitalise on them.

She was hired for Countdown Revolution on the proviso that she and co-host Mark Little, who was affectionately known to the nation as Joe Mangel in Neighbours, be as anarchic and crazy as they could possibly be. Their antics were a precursor to how Recovery would look on the same network just five years later.

Lacy and Little played up to the brief and their shtick became a ratings winner for the ABC. But that’s when things changed.

Tania Lacy with fellow Countdown Revolution host Mark Little.

Record companies threw big names at the show and the pair were told: ‘be nice or else’. When Little referred to the boyband New Kids on the Block as “shit” and tried to set fire to their CD, all hell broke loose.

“Gone were the cries for anarchy,” remembers Lacy.

“The new catch-phrase was, ‘Stop tape! Don’t say that. And roll tape’. We were no longer required to be anarchists. We were required to be the mouth-pieces to sell records,” she recalls.

Suddenly, record companies were paying for trips to the US to interview pop stars and new equipment and shiny prizes appeared out of nowhere.

“This did not sit well with either Mark or I. We worked for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, a government organisation that was free from the confines that advertising brings. This was part of their charter, possibly the most important part. In effect, Mark and I were being forced to break the law.

“We were frustrated and felt a deep sense of betrayal, not just from the show’s executives but also from within ourselves. We had betrayed our audience.”

Tania Lacy shot to fame hosting the revamped Countdown Revolution on ABC-TV from 1989-1990. Photograph by Peter Rosetzky.

Lacy could have ended her tenure with Countdown Revolution then and there, but a wild idea to go on strike while live-to-air got the better of both hosts.

“Our plan was simple. Go to air, dump the rundown, and tell the truth.”

If the producers wanted anarchy they were going to get it.

“We ripped up the rundown and said it like it was. ‘The revolution is here! We are now officially on strike!’”

The pair were cut off as they went to video tape.

Pandemonium broke out on the floor. No one had any idea what was going on, except Lacy and Little.

“The producer approached us asking what was happening,” remembers Lacy. “We explained we were protesting over their lies to us and those we had passed onto the audience. We no longer wanted to sell records for them so they could benefit with gifts and contraband.”

The revolution was televised and has since been removed from YouTube, but the payoff was that Lacy’s promising career came to a crashing halt.

The official word from the ABC at the time was that Lacy and Little were fired for staging a ‘mock protest against bands miming’. Lacy was fired by fax and told never to darken the door of the ABC again.

“My career fell into a deep hole and never truly recovered,” she says with regret.

“It was like I was tossed onto the rubbish heap and then continually kicked by bad media. I was twenty-five years old. Can you imagine how intimidating it was to have these powerful men in their fifties and sixties saying stuff to you? The power imbalance was devastating.

“That was the end of my dealings with the ABC. I was not even allowed back on the premises to empty out my desk.”

Lacy didn’t perform again in Australia for ten years. She took on writing jobs to support herself and was diagnosed with a mental illness. She also undertook intense counselling.

“We don’t accommodate mental illness in this country the same way we accommodate an illness like cancer. If you’ve got a mental illness there’s not a one-size-fits-all solution or cure.”

Lacy eventually fled to Germany, only returning to Australia during the pandemic. She’s been reluctant to talk about her experiences until very recently when she poured everything into an entertaining one-woman-show called ‘Everything’s Coming up Roses’ which she performed nationally, including at the Adelaide Fringe.

The response was almost life-affirming. Fans who remembered her from The Factory and Countdown Revolution had no idea what she’d been through, and the critic’s reviews were glowing. She was called a legend and an icon.

“There was a realisation that I was doing something special,” she states. “It’s like you’re put somewhere until people say, ‘Oh we’ve forgiven her and she’s learnt her lesson and isn’t she fantastic?’ But it’s a real double standard because men like Wayne Carey can be involved in a massive sexual scandal one week, then back on TV hosting a footy show a month later!”

Lacy has made Queensland home now, where misogyny still rears its ugly head in the unlikeliest of places. She recently entered a comedy competition where the three judges, and the host, were all male. She called it out and the judges turned on her.

“What country in the world in 2022 has no women on a judging panel? Every time a woman came out, the host would make remarks like, ‘Oh, we have another woman for you now’, and after every performance he would pick them apart. It completely pissed me off.”

What would Tanya Lacy have done differently, knowing what she knows now?

“I’m not sure I can answer that question because I don’t honestly know. I have had to navigate all this by myself and I’m okay with that now,” she says. “I’m working on my own shows and not relying on anyone else but me. I’ve taken my power back. That’s the most important thing.”

Two decades later, the music and entertainment industry’s most pressing concern is committing to safety and wellbeing for all women, and shifting the culture that has been allowed to permeate. Major label HR departments are setting up task forces to encourage diversity, leadership and wellbeing. Awareness around mental health and what is now considered acceptable behaviour is allowing the inclusion of prominent voices to rise to the surface.

With artists calling out perpetrators, and more women bravely coming forward to share their experiences, there is a renewed sense of hope for the industry moving forward.

We still have a lot of work ahead of us but the noise is getting louder as more and more women gain the confidence to break years of silence.

“I think a lot of women are realising now that we do have a voice,” says Melissa Tkautz.

“We are equal and I think we are becoming stronger and stronger — but I don’t want it to be a situation where women are anti-men. It’s all about respect and that’s a two-way street.”

Sound as Ever: A Celebration of the Greatest Decade in Australian Music 1990-1999 by Jane Gazzo and Andrew P Street is out now through Melbourne Books.

This article features in the September 2022 issue of Rolling Stone AU/NZ. If you’re eager to get your hands on it, then now is the time to sign up for a subscription.

Whether you’re a fan of music, you’re a supporter of the local music scene, or you enjoy the thrill of print and long form journalism, then Rolling Stone Australia is exactly what you need. Click the link below for more information regarding a magazine subscription.