Ashlee Jones

‘These Guys Will Go Down in the Hall of Fame as the Greatest to Do It’: Hilltop Hoods Ascend to the Pinnacle of Australian Hip-Hop with New Album

From rapping in parks as teens to hit albums and sold-out arena tours: how Hilltop Hoods fought their way to the top and made Australian hip-hop legit.

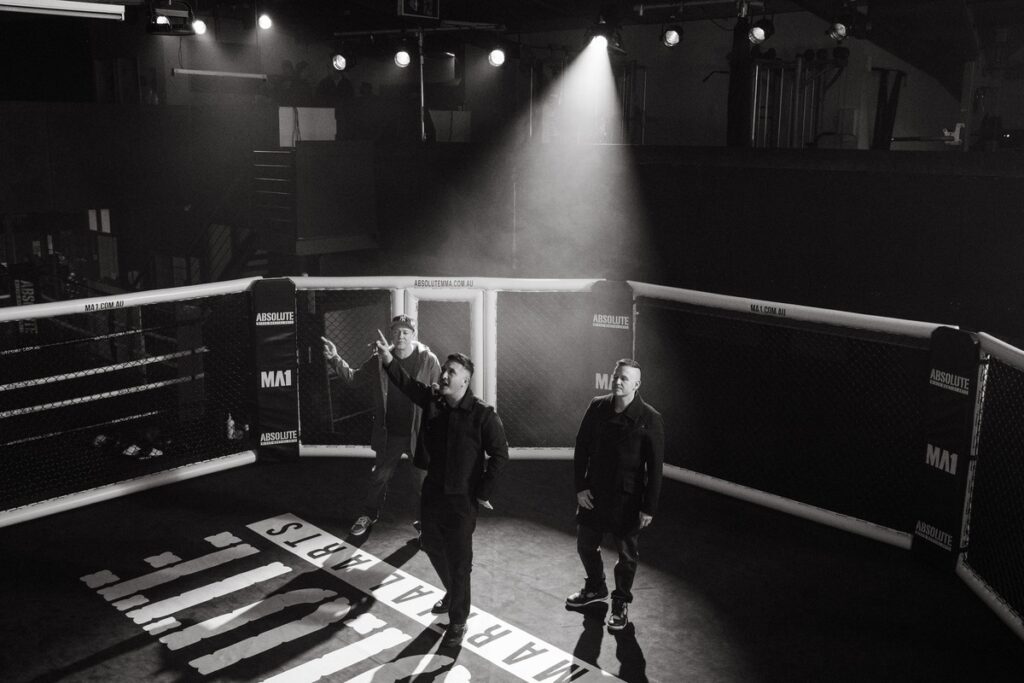

Collingwood, Melbourne. It’s a crisp winter morning on a Wednesday, and posing for photos on a narrow street outside an Absolute MMA gym is Australian hip-hop royalty Hilltop Hoods (much taller than you’d expect), and MMA royalty Alexander “Volk” Volkanovski, the current featherweight UFC World Champion (shorter than you’d expect, but considerably more imposing).

Once the pictures are taken, a jovial Volkanovski tells me he’s a long-time fan of the Hoods’ music, then introduces me to his training partner and protege, UFC bantamweight fighter Colby Thicknesse. The pair have flown into town to star in the music video for the Hoods’ single “Never Coming Home”, along with Matiu Walters from New Zealand pop-rock band Six60, who sings the chorus on the track. “I went to tell Colby they wanted him to be in the video, and I found him in the gym training to a Hilltop Hoods playlist,” Volkanovski tells me. “Meant to be.”

Image: Colby Thicknesse and Alexander Volkanovski on the set of Hilltop Hoods’ ‘Never Coming Coming Home’ music video Credit: Ashlee Jones

I wander over to meet the equally jovial and pretence-free Hoods — DJ Debris (Barry Francis), Suffa (Matthew Lambert), and Pressure (Daniel Smith) — and ask if shooting music videos is something they enjoy after making over 30 of them. “Yes and no – they’re always long days. I personally don’t love being in front of the camera, I’m not like a theatre kid,” Lambert says with a laugh. Smith, a huge UFC fan, is excited to see one of his heroes in action. “There’s always fun moments,” he says. “I’ll really enjoy watching Volk and Colby do their thing and throw a few punches, which is something I don’t get to see every day.”

“Never Coming Home” is a rousing anthem about striving for greatness, and a track that sounds custom built for a fight-training montage in a film. “The song’s about going on a journey to find yourself and create your mark in the world, being determined to make it happen and not resting on your laurels until it does,” says Smith. “It’s got a fighting spirit.”

Volkanovski is a perfect fit for the music video, but look a little closer, and undeniable career parallels between the Wollongong-bred fighter and the Hoods start to emerge. Both are the reigning champs in their respective fields, yet are approaching an “elder statesmen” status where some are expecting — possibly even willing — them to slip from the top spot; to deliver less powerful hits as time marches on.

The group laugh heartily when I suggest Hilltop Hoods are the defending champs of Australian hip-hop, but it’s an entirely valid proposition when you take into account the Adelaide group’s incredible achievements: 89 platinum accreditations (2003’s The Calling was the first Australian hip-hop album to go platinum), 1.1 million album sales, over 1.8 billion global streams, six consecutive No. 1 albums (2006’s The Hard Road, the first Australian hip-hop album to hit No. 1, through to 2019’s The Great Expanse), the most entries into triple j’s Hottest 100 for an Australian artist, “The Nosebleed Section” coming in at No. 2 on triple j’s recent Hottest 100 of Australian Songs, 10 ARIA Award wins, and multiple sold-out arena tours. Forget hip-hop — it’s a stunning run of success for any act, regardless of genre.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“Sometimes it feels like we’ve been in the game so long that people want to see us fall from the throne – not that I’m saying the throne is ours solely,” says Smith. “Sometimes there are people in the landscape that feel like if they push you out of the way, it makes space for them, and that’s just not how art works. [New album Fall from the Light] is a bit of a pushback on that idea.” Still, he smiles when imagining Hilltops Hoods taking on all comers in a title fight. “We’ve been up there for at least as long as Volkanovski’s had the crown.”

“In hip-hop, early on with the battles and stuff, it definitely was competitive for us, but what [Volkanovski] does is combat, and I just don’t know how something creative and subjective is a competition, you know what I mean?,” says Lambert.

“From my perspective as a music fan, there’s people out there that sell millions of records and do huge world tours, and at the same time, a guy that I’m listening to at the moment who’s got 15,000 listens on his shit, I think he’s amazing, and I think that fucking star is a fucking loser (the room erupts into laughter; the star’s name isn’t mentioned, but everyone seems to know who’s being referenced). So it’s all about perspective – you can have the numbers, but you can’t be the winner because it’s objective in your own head.”

Image: Hilltop Hoods and Six60’s Matiu Walters on the set of the ‘Never Coming Coming Home’ music video Credit: Ashlee Jones

We move inside the darkened gym, where various production people busily scurry about doing their jobs. Six60’s Walters films his scenes inside the imposing octagon, a location that typically plays host to brutal fights, not music stars miming songs. Volkanvoski and Thicknesse are warming up for their scenes nearby, moving with the kind of graceful ease and precision that only comes from years of dedication and hard work. Sometimes it takes a relentless drive and obsessive attention to detail to be the best.

“The older I get, the harder it is to put out stuff,” Lambert cofesses. “When I was younger, you’d just make a song, put it out, and wouldn’t really think about it. And as you get older, you start thinking, ‘how should I say that?’. For me, that has magnified over time to the point where on the last album [2019’s The Great Expanse], I did 1,200 to 1,400 takes for ‘Leave Me Lonely’. I make demos when I write something, and then I get it in my head how I want it exactly [to sound], and I get sort of trapped by that. I’m a bit like my own worst enemy in that sense, but I guess it pays off as well if you’re attentive to detail. You still need to know when to step away from it, but I think it’s just a combination of I’ve been doing it for a long time, plus some innate pedantism as well.”

According to Lambert, Hilltop Hoods have never been as thorough as they have been on ninth album Fall from the Light, the group’s first LP in six years. Smith says that a quest for perfectionism — which he admits can never be met — has been a big focus of the album, and is one of the reasons why it took so long to arrive.

“We did promise fans the album a little earlier than it came out, but I think at the end of the day, when people hear the record and they hear how much work we’ve put into the 12 songs, they can appreciate it as a detailed body of work that flows from beginning to end,” he says. “A lot happened in the world after 2019 – we did about 95-ish shows around the world off the back of our last album, and then COVID hit, and I personally was quite burnt out.

“I just needed some rest, and I have young kids that I want to spend some more time with. So it was kind of a break that was forced upon us, but I needed it to reinvigorate, to get excited about making music and I think it shows in Fall from the Light. The time we have taken to make this record is definitely one of its strengths.”

With intense passion and perfectionism going into every bar and every note of music from each member of the group, it’s no surprise to learn that sometimes things can get a little heated. Although said with a smile, Smith told Triple J Magazine in 2011 that “It’s not a record if we haven’t had one big blowout during the making of it.”

I ask Smith if that has held true for the making of Fall from the Light.

“It sure has,” he laughs. “The week we handed the album in, [Matt and I] had quite a fight (“I’m Switzerland in the group,” Francis tells me later). We hugged it out the next day. It’s over the same thing every time. When you’ve got two creatives in the same space that are both very passionate about the music, sometimes there’s a difference of opinion on how a song needs to sound. I think when we wake up the next day we laugh about it, and continue on.

“We both have a very clear vision that’s very similar to how we want Hilltop Hoods to sound, and we’re still both on the same track there. That’s never wavered. We’re at a place where we’re super comfortable with who we are, we know what kind of music we want to make, we know our values, we know where we stand in the world, and it translates into the music.”

Image: Suffa (Matt Lambert), Pressure (Daniel Smith), and DJ Debris (Barry Francis) Credit: Ashlee Jones

Spinning the Wheels of Steel

In 1987, New York City hip-hop pioneers Public Enemy included a track on their debut album Yo! Bum Rush the Show titled “Terminator X Speaks With His Hands”, an irreverent nod to the fact that rappers do all the talking, while the DJ stays silent and strictly does the record spinning.

The role of Barry “DJ Debris” Francis in Hilltop Hoods is no different, but that doesn’t mean he has nothing to say. As we drive around Melbourne while his bandmates perform in front of the camera back at the gym, he proves himself to be the dark horse of the group, a man who’s extremely knowledgeable about a wide range of subjects, from the nuances of recording a full orchestra for the Hoods’ series of Restrung albums, to the dystopian topic of Facebook using data scientists to study and manipulate user behaviour. He’s also a qualified audio engineer – a skill earned via completing a course when he was a young man. The course was paid for by Francis’ father, even though he wasn’t exactly a fan of hip-hop.

“The first time I did a Channel V interview [on TV], the host asked me if I had any messages for anyone, and I was like, ‘Yep – this is for you, Dad,’ and I gave him the middle finger,” Francis laughs. “He was a bit [like], ‘You’re a fucking loser, go get a normal job.’ He did support me in paying for a degree in sound engineering, but he always saw me as an artist chasing a pipe dream, thinking it was never going to happen. But when it did, he had to eat his words.”

Hip-hop may have rubbed him up the wrong way, but Francis Sr. was unwittingly responsible for his son’s first foray into DJ culture. “I can’t remember what it was that inspired me to try scratching for the first time, but my Dad had a direct drive record player and an amp with a switch on it, and I worked out you could kind of crossfade with it,” he says. “I was scratching my sister’s 45 record of Madonna’s ‘Vogue’, of all things. I knew I had a natural rhythm for it, and kind of just took it from there.”

Although it has now become a cultural juggernaut that has dominated the charts for decades, hip-hop in the Nineties, particularly in Australia, was widely derided by mainstream music fans as being nothing more than a fad, and sneeringly labelled as “not real music” by many – especially the rock ’n’ roll bands of the era.

“When we first started doing festivals, I remember you’d hear the other bands being like, ‘Oh, here come the homies,’” says Francis. “It’s funny – we’re still playing shows, and the people I heard those whispers from, I don’t see at festivals anymore.”

Despite their status as a hip-hop group making them instant outsiders, Francis says there was a flourishing local scene in the Nineties which helped the Hilltop Hoods hone their craft. “All the artists in Adelaide just happened to be from the southern suburbs – it was a very concentrated group of artists in a small geographic area, which I guess played a huge part in punching through the skepticism of the general public,” he says. “I remember a lot of different groups and artists – we all kind of inspired each other. There were so many rappers in Adelaide at one stage. It’s an interesting place for it to have flourished, to be honest. I guess being isolated helped us form a community and foster creativity.”

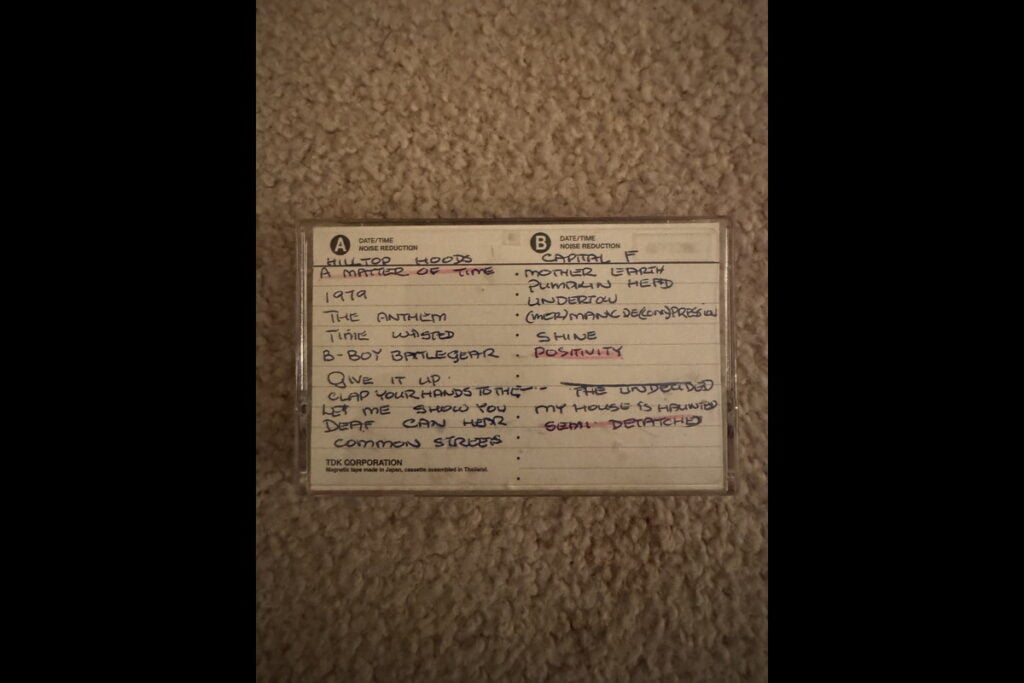

Image: A cassette featuring Lambert’s mum’s handwriting with the first Hilltop Hoods EP on the A side, and Lambert’s brother’s band on the B side Credit: Supplied

Francis became Hilltop Hoods’ full-time DJ in 1999, taking over from multiple South Australian DMC championship winner Ben “DJ Next” Hare. He remembers making the group’s early music on antiquated equipment (“We’d work on two Amiga 500 computers with 1MB of RAM each – it was worse than cassette quality”), and utilising the analog studio where he was studying audio engineering.

“When we started, the only way you could record was reel to reel tape, so you needed access to a million dollar studio, or you’d hire one and end up with an engineer that wears UGG Boots and doesn’t understand what a drum machine is,” he says with a laugh. “I remember the first records were done like that, which was so restricting, financially and time-wise. I remember biting the bullet and deciding that we should get our own equipment, and that was when digital audio editing had just come out. That opened up a whole world of being able to work in our own time frame.”

Nine albums and countless hit songs later, Francis says that playing live shows is the thing that he cherishes the most from his time in Hilltop Hoods. “There’s nothing better than a crowd singing in unison,” he says. “Nothing puts the hairs up on the back of your neck more than that. Often I’ll see a 50-year-old dad and his 15-year-old son bonding in the front row, and shit like that, it’s just priceless when you see it. You’ve given them something to experience together. Often I’ll be halfway through a set and I’ll spot something in the crowd and just go, ‘this is why I do this.’”

Image: Hilltop Hoods live Credit: Joseph Mayers @josephmayersphotography

Our chauffeur, the group’s long-time manager Dylan Liddy, drops Francis back to Absolute MMA Collingwood. He tells me he was inspired to work with the group after catching one of their live shows in the early Noughties. “A fellow by the name of Richard Moffat, who used to be a very prominent booker of venues in Melbourne, he rang me up and said, ‘Come down and see these chaps called Hilltop Hoods,’” he tells me. “I’m a bit of a metal and rock dude. I traveled to see one of their five sold-out shows when ‘The Nosebleed Section’ was breaking, and I remember buying a beer and I had half a pint still left at the end of the show because I was just watching dumbfounded, going, ‘What is this?! This is amazing!’ I pretty much just said to them, ‘I wanna be next to this.’”

Although Hilltop Hoods weren’t the first Australian hip-hop group to be signed to a major label (that would be Sydney’s Sound Unlimited, who released their debut album on Sony in 1992), they are undeniable pioneers when it comes to making Australian hip-hop a viable commercial force in this country, despite the resistance they faced along the way from punters and industry folk alike.

“[Their music was] a genre which was quite frankly shunned by the industry for a long time and wasn’t taken seriously and was considered just a try-hard derivative form of whatever people perceived as hip-hop coming out of America,” says Liddy. “And they proved that wrong. They talked about Australia, they talked about their experiences in Adelaide, and they did it in an Australian accent, not an American accent.

“Radio stations back then would boast they didn’t play any ‘rap crap’, and we were shunned at festivals in terms of being slid down and given crappy spots, even though what we were bringing to the festival was bona fide numbers. That’s changed, so I feel they were very instrumental in helping other hip-hop artists who did all the grinding as well. We were banging on doors for a long time, even though they were doing sold-out shows and making platinum records. It was just getting through a bit of a cultural barrier in the Australian music industry, and Australia in general.”

Image: Hilltop Hoods on the set of their ‘Never Coming Coming Home’ music video Credit: Ashlee Jones

That persistence to kick down doors and not give in to resistance, Liddy believes, stems from the fact the members of Hilltop Hoods have been firm friends since high school.

“Obviously they’re on the same path, and there is a friendship, but I think it’s beyond that,” he says. “I think there’s a deep love, like a brotherhood, like a family. Like all families, you have your ups and downs and there’s different dynamics at different times, but the continuity is a genuine respect and love for each other and their respective families. And it’s not always easy, it’s not. But the intent, which I think is a really important word, the intent is always to try and keep to the roots, and do it with each other through thick and thin.

“They’re very gifted and they’re very driven, and the combination of those two qualities is definitely fundamental in their continued career. It also helps that they’re a phenomenal live act – they’ve been playing festivals here and overseas, arenas, clubs, theatres, underground dive bars when they first started. They’ve just been grinding, and even before that, they were spitting in their local parks, learning their craft. You don’t just all of a sudden play arenas.

“We headlined Bluesfest recently, which was one of our first gigs back for a long time, and it was just packed. It was crazy. The hair on the back of my neck stood up, whether that’s a reaction to the euphoria of the band or the audience. I constantly pinch myself being around such great energy and art. I’m forever grateful.”

Image: Hilltop Hoods on the set of the ‘Never Coming Coming Home’ music video Credit: Ashlee Jones

The Sport of Rapping

Back on the set of the music video, Francis, Lambert and Smith have wrapped their scenes. The humbleness and self-deprecating humour that naturally flows between the trio is in stark contrast to the attitude of many American MCs, where braggadocio and proclaiming yourself to be the “best rapper of all time” is part and parcel of the job. “I do like that though – you don’t want to hear a rapper with low self-esteem, it’d be dog shit,” laughs Lambert. “Sometimes they’re my favourite songs,” says Smith. “Just rapping for the sport of rapping. It’s great.”

Hilltop Hoods have now been participants in the sport of rapping for over 25 years. Lambert and Smith bonded over hip-hop in the early Nineties while students at Blackwood High School in the Adelaide suburb of Eden Hills, the pair obsessed with the rap music that was coming out of the US at the time – foundational artists like N.W.A, A Tribe Called Quest, Eric B. & Rakim, Gang Starr, and Public Enemy (“After we played Groovin the Moo a few years back, Chuck D came into our tent and called us the ‘young Beasties Boys’ — I fanboyed the fuck out,” says Smith).

“I think in the second year of high school, Matt and I bludged school, combined our pocket money and caught the train into the city,” recounts Smith. “There was one record store back in the day that used to have rare imports, like underground rap music. We went halves on a cassette of Ice-T’s O.G. Original Gangster album, and it was like this adopted child that used to spend one week at my house, and one week at Matt’s house.”

Smith says his parents were initially not fond of his newfound passion.

“My parents always took me on road trips, caravanning and camping, and we would have a cassette player in the Ford Cortina. I would put on stuff like Run-DMC, Public Enemy and N.W.A. My parents would be like, ‘Daniel, this music’s not appropriate,’” he laughs. “They would let me play the music even though my mum hated it. She got to know the music so well on N.W.A records that she knew where the swear words were and hit [the fast forward button]. That tape got worn out real quick.”

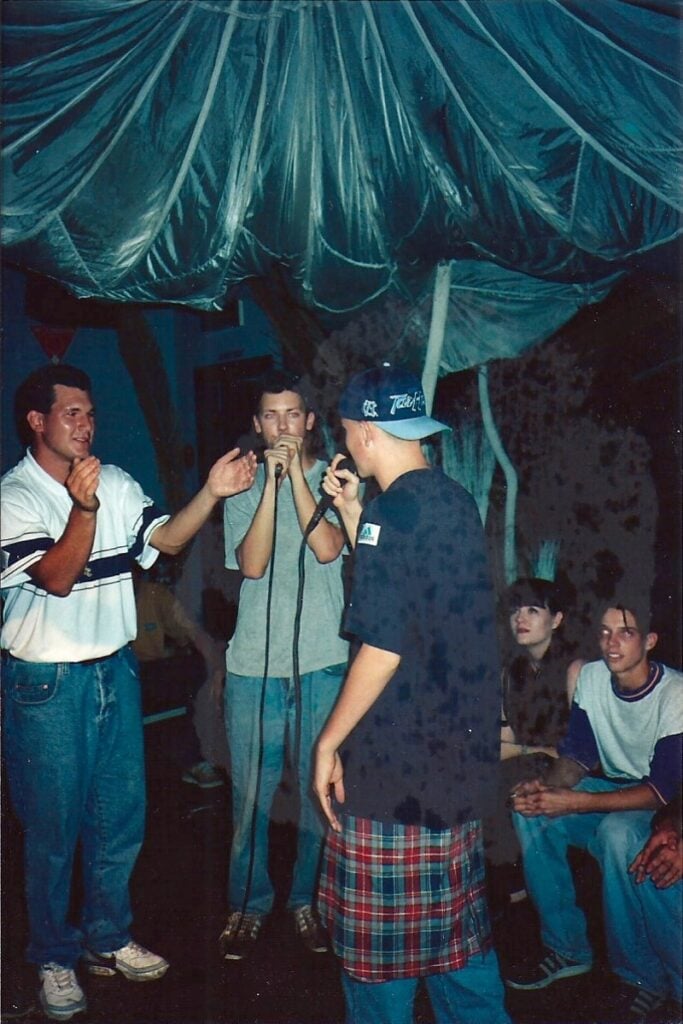

Image: Flak, Suffa, and Pressure at an open mic night in the Nineties Credit: P J Murton

Smith’s hip-hop fandom soon translated into writing and practicing his own rhymes, a skill he flexed live at club shows while he was still underage. “We had this family friend named Flak, who was a well known pioneer in Adelaide’s underground rap scene,” says Smith. “He was one of the people that handed me rap music. He snuck me into this nightclub when I was 15 years old, and with an ego far larger than it should be. He got me on stage and was just like, ‘Now you gotta battle with them,’ and I was like, ‘Oh, OK,’ so I started to freestyle against these older guys. They were maybe 19 or 20, but it was still pretty intimidating. I remember walking away feeling pretty good about it.

“Matt and I started doing stuff together shortly after that, and it was a couple of years that we did [small club appearances]. There’d be a DJ playing breakbeats on two turntables with vinyl, and we’d just get up and freestyle. The competitiveness of rap became combative and you’d just end up trying to do better than the guy before you and the guy after you. We’d also get an older brother of ours to buy us a few beers and we’d sit in the park when we were underage and just rap.”

Smith also credits his post-high school day job working in a warehouse as an important factor in his growth as a writer and MC.

“I was a warehouse manager for a wholesale company, and I wrote about two albums in that warehouse, it was awesome,” he laughs. “My parents actually owned the warehouse, and my Dad found all these scribbled raps that I’d written and hidden in all these places years later. He said to me, ‘I knew you were writing raps the whole time. It kind of annoyed me, but I let it go. What annoyed me most was how shit your spelling was!’”

Image: Nyassa Credit: Michele Pitiris @sheisaphrodite

As everyone departs for their various flights home, I call Nyassa, a young Adelaide pop artist that Hilltop Hoods have featured on songs from their last album The Great Expanse (“Be Yourself” and “Here Without You”), as well as new album Fall from the Light (the title track opener, and closer “The Moth”). As she prepares for an upcoming UK and European tour with the group, I ask for her thoughts on their influence.

“For me, coming from Adelaide, which is such a small place, they are such an inspiration, because they’ve also come from where I’ve grown up and it’s like, look at what you’ve done with your life, look at the career you’ve made coming from such a small place,” she says.

Hilltop Hoods have a strong record of working with up and coming artists (see: Ecca Vandal, Ruel, Adrian Eagle, and Montaigne, among others), something that Nyassa says she has also benefitted from.

“They’re always getting behind people who they think should have more recognition, and they want to champion upcoming artists because they’ve got that platform and know how it feels to be an emerging artist in Australia,” she says. “When I was on their last album, I hadn’t put any music out yet. They just care so much about finding new talent and choosing that over perhaps a more high profile choice. When I found out that I was gonna be on this album, I cried because it just means so much to me, that belief they have in me as an artist.

“Now they’re like my three big brothers… They are the best people.”

Image: Trials Credit: Tristan Edouard

Next I speak with Ngarrindjeri rapper, songwriter and producer Daniel “Trials” Rankine, formerly of Funkoars, one half of A.B. Original, and an in-demand composer (he’s recently finished the score for Top End Bub, the TV show follow-up to the hit film Top End Wedding, in addition to completing work on a hotly anticipated debut solo album due out later this year). His history with Hilltop Hoods runs deep, going from a fan to a friend to, eventually, a collaborator (“I’ve definitely [done] the most remixes with them and had the most cameos in their film clips — I’m killing everybody for those records,” he tells me gleefully).

“I heard about the guys from friends giving me music recommendations when I was in high school — one of my friends gave me a cassette tape that had Wu-Tang Clan’s Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) on one side, and [1997 Hilltop Hoods EP] Back Once Again on the other side,” says Rankine. “I just religiously played that record over and over and over again, man – I can’t even tell you how obsessed I was with it. I eventually bought a copy and there was a contact address in the liner notes. It was a PO box in Lonsdale, which was two suburbs away from where I grew up in Hackham South, which is a super low economic area in Adelaide. It just blew my mind that this world-class music I was hearing was being made a couple of suburbs away.”

At 17 and already a burgeoning producer, Rankine was invited by a friend to see a show by Cross Bred Mongrels, another hip-hop group Francis was a member of. After being invited on stage to rap (“It was some real godawful rhyme — I don’t know what it was, but I just know it was bad”), he befriended Francis, who became a mentor. “I was pretty inseparable from Debris’ house,” says Rankine. “I grew up on that dude’s couch just watching him produce, and I was just completely infatuated with [Hilltop Hoods’] ability to do it all and have foresight for things that I just couldn’t even imagine. These guys were so across everything so early in the game, and were airtight and knew who they were from the jump.”

Rankine likens the trio to the animated character Voltron, a giant robot made up of five piloted mechanical lions that meld together. “I would put Suffa as the heart. I’d put Pressure as the arms, the muscle. I’d put DJ Debris as the head, easy. The amount of knowledge that Barry has is a hard drive, you know what I mean? Like, that dude is next level.”

He tells me that the impact Hilltop Hoods have had on the Australian hip-hop scene — and himself in particular — is nothing short of monumental.

“There’s the surface stuff with all the records that they’ve broken and all the accolades and awards and achievements, but then there’s all the underground stuff that those guys are responsible for that will never be told or understood,” he says. “For example, when Briggs and I had the idea to do the A.B. Original project, we cut five songs in a couple of weeks, and that was sort of it. I showed it to Suffa, and he immediately said, ‘Well, what we’re gonna do is we’re going to change this to 10 songs, and you’re going to make this an album, and this is what we can do with this.’ I know that guy, and I know that when he believes in something, he’s seeing something that I haven’t seen yet, but I will. I trust him intrinsically.

“There’s small things like that that wouldn’t have happened without the pushing and the faith and the trust that these guys have had in me. I think that applies to the entire scene in general – honestly, I can tell you at least 10 stories straight off the top of my head where albums that have culturally shifted the momentum or started a conversation or just lifted the game, [Hilltop Hoods] are indirectly responsible [for them]. That’s the real history.

“The other thing that really inspires me every single day is the selflessness that these dudes have. They are easily the most undersung humans I know, and I owe them so much. Every time they upgraded their [recording] setup, they would give me their old shit. If it wasn’t for those dudes, I wouldn’t have the career I’ve had for the last 20 years.

“Not only are they my best friends, they’re the best at what they do — and what I want to do as well, which is not just make killer music, but also inspire people around me. They’re top tier MCs, producers, DJs — every single aspect you can think of in the game — but they’re even better people, and you won’t find a single human in the industry or the scene who will disagree. These guys will go down in the Hall of Fame as the greatest to do it.”

The Gift

Universal Music Australia’s Sydney headquarters, one week later. Hilltop Hoods are in town for various media appearances to promote Fall from the Light, which is still another six weeks away from release. I meet Lambert in the office of Universal Music Australia’s President Sean Warner, a large, luxurious space that has framed photos of everyone from Stevie Wonder to Lady Gaga on the walls, and a million-dollar view of the city.

I ask Lambert about two of the album’s key tracks: “This Year”, a candid song that details his struggle with depression, and “The Gift”, a song with a verse Lambert wrote about his late father.

“Like a lot of people during the pandemic, anything that you’d had in the background sort of came to the front, and I felt it in myself,” he says. “I made the decision to go and talk to someone about [depression] and to actively take it on, because I’d never discussed it. I realise now that I was embarrassed, and it wasn’t until I gave it a name and started talking to someone about it that I was able to deal with it and improve things.

“I was only able to do that because of other people talking about it and not being ashamed or embarrassed about it, and I wanted to do something that I thought was the most honest and accurate description of dealing with depression that I could, in the hopes that other people could identify with that and go, ‘That’s what I’m dealing with and I wanna take it on as well.’ It can’t be overstated enough how helpful it is for people to talk about it, and how destructive it is to have this shame, because I’m not ashamed.

“When I look back, I think my dad probably dealt with it, and when I look back at my grandpa, I think he was probably dealing with it, and I want to be on the front foot with it. I went through bouts of depression where it was pretty bad, but I feel like I’m coming out the other side of that, and part of that journey was writing [“This Year”]. It was so cathartic to write that and put it down like ‘this is what it is,’ and to understand it. It was a big deal for me. It’s really helped me and I’m hoping a lot of men, although it’s not restricted to men, can identify with that, and hopefully it helps out.”

Back in Melbourne, Smith had told me that the album’s first single, “The Gift”, was the cornerstone of the record, an “ode to our families — the three of us came from very musical households, and we were lucky enough to have parents and other family around us that handed down such great music and such great memories.” Lambert wrote the chorus for the song not long after his father, a guitarist and avid music collector, passed away.

“‘The Gift’ is about our journey through music and family… it’s got a lot of heart, I reckon.” Lambert pauses as grief takes hold. He breaks down into tears. “Sorry. I haven’t talked about ‘The Gift’ because it was after I lost my old man… we had a rough relationship, so it was me reflecting on, ‘What did he give me?’ From him, it was music. And now music is my life. For me, that was like the cornerstone of everything we did on the record. Once we’d finished that, the record sort of made its way from that track and propelled us toward finishing it.” (“Matt’s father absolutely loved music, and he used to turn up at festivals here and there around the country,” Smith tells me later. “I like to think that he’d be very proud of what Matt wrote for him.”)

A while later we’re joined by Francis and Smith, the pair fresh off doing interviews for radio. The trio become animated when talking about hitting the road again: they’re about to embark upon a UK and Europe tour, and have an Australian arena tour locked for 2026.

“For me, we’re a live band,” says Lambert matter-of-factly. “If we’re not touring, we’re not being a band.”

“Nothing has faded for me in the sense of how much I love performing,” says Smith. “I still love that human connection and it’s an energy rush that you can’t get anywhere else. Giving music to a crowd and watching the energy transfer between them and you, performing songs that people know and love in front of them, it’s an amazing thing. To still be able to do that around the world, that never grows old. I just want to be able to put new songs out to people who are genuinely vibing on them.”

Although they are not the types to coast on past glories or wallow in nostalgia, I ask them what it’s like to look back on a storied career after fighting their way to the top of the hill.

“I just reflect on how lucky we are,” says Lambert. “With the timing that we were able to be there at the beginning of this [hip-hop] movement in Australia, that particular right exact time where [hip-hop] took over the radio and the internet had democratised everything, but it hadn’t quite reached saturation. It was this perfect convergence of things. I think how difficult it would be to achieve what we have achieved if we were starting out now – I’d say nearly impossible, which makes me sad for artists coming through now. It was a time when persistence and consistency meant something more than it does today, I guess.”

Now that Hilltop Hoods have lasted far longer than most marriages (in Australia, the median length of a marriage that ends in divorce is approximately 12 to 13 years), I ask the group what’s kept things together this long, and what keeps them hungry, still pushing forward to do the best they can after decades in the game.

“Fundamentally, us being friends first and respecting each other’s decisions is why it still works,” says Francis. “If one of us is opposing an idea, we don’t try to do the ‘but two out of three of us said yes’ thing — it’s all or nothing. We don’t fight over much, and being friends first and foremost is probably at the core of it.”

“There’s an energy between us. Whatever it is, it’s intangible,” says Smith. “We have a formula or a cohesion that works for some reason. I couldn’t be more thankful that I get to do what I love for a living. I pinch myself every now and then. Over the journey of 25 years or more of being a songwriter, it’s really important to know that people are still connecting with you on a human level, because you can lose perspective and lose touch with the fan base – I see artists do it all the time. I don’t think we have, and that’s important to me.

“Having a relationship with your bandmates is not that dissimilar to having a relationship with a partner or your parents. They all require work, they all require you to give way sometimes. Things don’t last that long unless there’s love and respect and deep understanding.” Smith breaks into a wry grin. “After music’s done for me, I’m gonna go into marriage counselling. My other two bandmates might disagree that I would or would not be a good marriage counsellor.”

“I still enjoy and get excited about making music,” says Lambert. “I’ve still got 4,000 voice memos in my phone, and most of them will never be realised. But I don’t think [creativity is] something you can turn on and off. You’re born, it’s on. And then when you die, it’s turned off.

Image: Suffa, Pressure, and Suffa’s brother Chris on bass as they perform in the Nineties Credit: P J Murton

“For me, it helps being in a group with someone who’s fucking as good as [Smith] is at what he does, because it drives you. You’re only as strong as the people around you. To go back to Volk, if Volk was training with someone who couldn’t fight when it came to a fight, it wouldn’t work. If you didn’t have competition your whole life, you’d suck. You definitely get better by putting yourself in the space with the people who are the best at that craft.”

“You’re not gonna continually progress, particularly when having done it for as long as we’ve done it,” adds Smith. “I couldn’t imagine [a sparring partner] not being there. Maybe we wouldn’t have progressed as far as we have for as long as we have if we didn’t have each other to bounce off.”

As they sidle out the door to their next engagement, I pull Lambert aside to ask what his teenage self — that kid drinking beer and rapping in the park and sharing hip-hop cassettes with his best mate — would think of him now.

“He would be baffled. When we were kids, it wasn’t like we dreamt of having a career in rap because it wasn’t even a thing to dream of. It was just not within the realm of possibility – we couldn’t think ‘oh, we want to do that,’ because there wasn’t anyone there in [Australian] hip-hop that had a career of it. So he’d be baffled, but he’d be happy… I’d like to think he’d be happy.”

Hilltop Hoods’ Fall From the Light is out now.