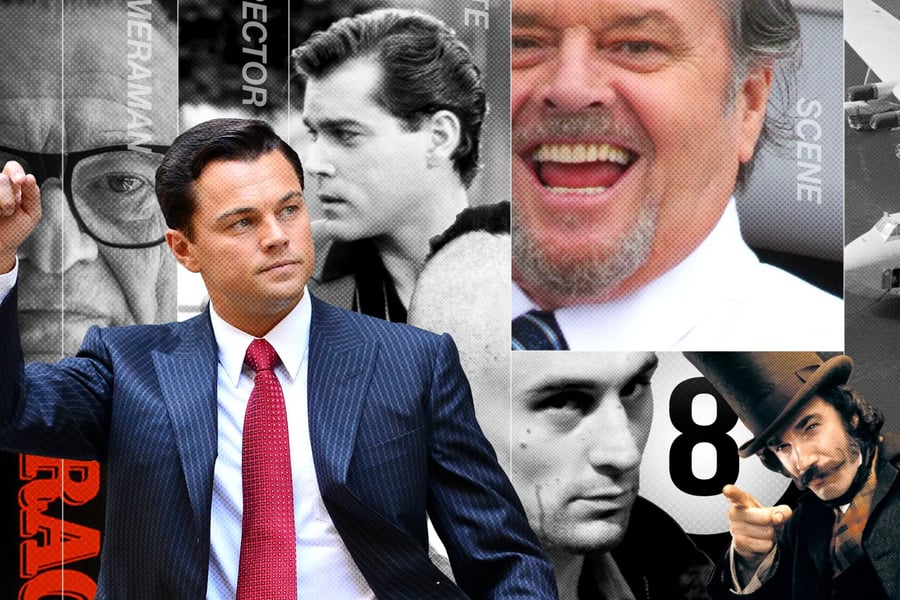

Every Martin Scorsese Movie, Ranked From Worst to Best

From ‘The King of Comedy’ to ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ — we break down the greatest living filmmaker’s career from bottom to top

ILLUSTRATION BY MATTHEW COOLEY. NETFLIX; JAMES DEVANEY/WIREIMAGE; WARNER BROTHERS/EVERETT COLLECTION; HERBERT DORFMAN/CORBIS/GETTY IMAGES; JAMES DEVANEY/WIREIMAGE; MIRAMAX/EVERETT COLLECTION

WHEN MARTIN SCORSESE’S true-crime epic Killers of the Flower Moon hits theaters on Oct. 20, it will be just short of 50 years to the day when Mean Streets, the director’s breakthrough movie, opened in his hometown of New York City and announced a major new talent. Back then, he was part of a wave of young, movie-mad kids who wanted to turn Hollywood inside out and reinvent genres for a new era. Five decades later, Scorsese is now widely considered the greatest American filmmaker working today, as well as the torchbearer for keeping the concept of cinema as an art form alive. Along with his stable of vital collaborators, he’s given us tales of garrulous gangsters, volatile loners, conflicted holy men, comedic kings, empowered single moms, downtown losers, Wall Street winners, and an all-too-human messiah. Most of these films are part of the informal canon of Movies You Must See Before You Die. Many are iconic. None of them are superhero movies, unless you count The Last Temptation of Christ. A handful of them are undeniable, ride-or-die masterpieces.

Ranking Martin Scorsese’s movies from worst to best requires scare quotes around the term “worst” — the man’s track record in terms of quality is surprisingly high, even if he’d be the first to tell you (likely at a speed that defies the human ear and the cognitive part of your brain to keep up) that his films have rarely been box-office successes. His allegedly lesser works are often more interesting, more thought-provoking, and more kinetic than a lot of his peers and acolytes’ greatest achievements. It’s just that, well, some Scorsese movies are better than others.

So, after countless arguments and narrowly avoiding some LaMotta-level punches, we’ve come up with our ranked list of Scorsese’s complete filmography, from the merely good to the greatest of them all. (Make that mostly complete — we’ve grouped some of the shorts and several docs together.) There will be disagreements, to which we reply: You arguin’ with us? I don’t see anyone else here, so you must be arguin’ with us.