Carol Ruff*

Waanyi artist Gordon Hookey has spent a lifetime raging against the system to explore these themes. The recent anniversary of Cook’s arrival at Botany Bay, and the events since, show why Hookey’s message matters more than ever.

In April, the ‘history wars’ rhetoric was sparked once again thanks to comments comparing Captain James Cook to COVID-19. Waanyi artist Gordon Hookey has spent a lifetime raging against the system to explore these themes. The recent anniversary of Cook’s arrival at Botany Bay, and the events since, show why Hookey’s message matters more than ever.

It’s been 250 years since Captain James Cook first set foot on the sandy shores of Botany Bay. His first encounter with the Indigenous population there resulted in gunfire. Since that meeting, everything has changed. Since that meeting, nothing has changed.

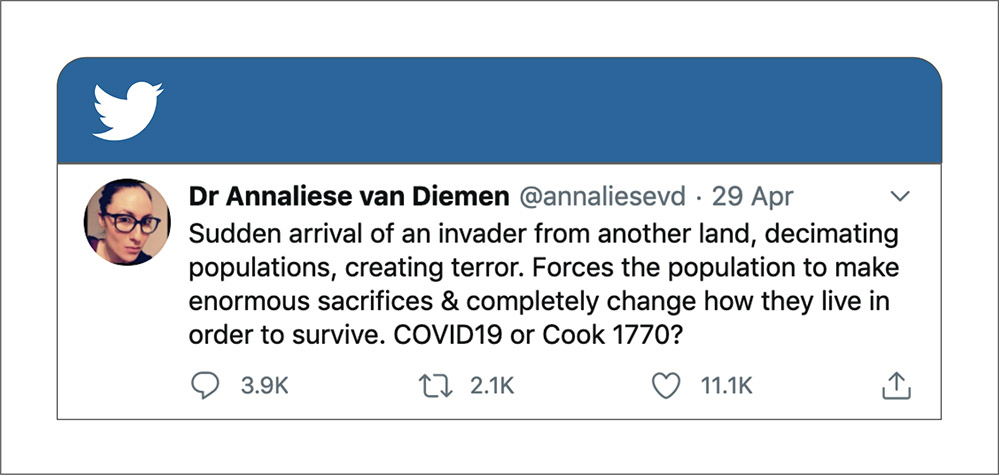

Back in April, Victorian Deputy Chief Health Officer Annaliese van Diemen was savaged online for a tweet comparing Cook with COVID-19. MPs and media commentators were calling for her resignation while the PM effectively told her to stick to her day job.

Deputy Chief Health Officer Annaliese van Diemen likened the impact of the arrival of Captain Cook to COVID-19

It’s easy to write this off as just another virtue-signalling mud fight in the onslaught of childish ‘culture wars’ rhetoric that stands for politics these days. However the comments and the ensuing fallout give us a glimpse into the vast chasm of misunderstanding over Australia’s colonial legacy.

For one thing, Cook was not an invader. He merely charted the East Coast of Australia. Colonisation came later; in 1788 with the landing of Arthur Phillip as the head of the First Fleet. But Australia has made Cook a symbolic forefather – and subsequently tied him to all the horror that was to come.

Professor Mark McKenna is a Cook expert from the University of Sydney who says the story of “Jimmy Cook who took our land” is an enduring one in Aboriginal oral tradition. “He’s a kind of stand-in figure for a lot of Aboriginal people, to represent the whole of British colonisation.”

Myth is something both sides have in common. Earlier this year the Morrison government pledged $6.7 million to sail a replica of Cook’s ship, HMS Endeavour, around Australia – something he never did. It was part of a wider $50 million package to mark the anniversary.

The idea was both praised and attacked – familiar territory when talking history. In the Howard era, academics, artists, and activists were attacked for presenting a “black-armband” view of history that was thought to be needlessly negative. The debate descended into what is now called the History Wars and it became clear to many that this is a conversation too difficult to have.

Artist Gordon Hookey. (Photograph courtesy of Milani Gallery.)

There is truth to the idea that struggle and conflict are great fuel for artists. At the height of this debate, Gordon Hookey, a Waanyi artist from Brisbane, painted a piece called Cognative frontier. It arrestingly captures the psychological barriers that promote conflict between the Indigenous population of Redfern, the police, and media who monitored them.

Twenty-five years later, the furore around van Diemen’s remarks suggest we may not have progressed much in coming to terms with our colonial past.

“I painted that when I had a studio in Chippendale,” Hookey tells Rolling Stone Australia. “It was on the fourth floor, and the window of that studio was actually facing The Block, facing the TNT building in Redfern. I was hanging out with some of the Kooris down there, many of them having lived on The Block, and their stories about the police actually leasing a floor [of the TNT building] just for surveillance of The Block area, that work came about from that.”

The Block is a famous Indigenous-owned housing project in the heart of Redfern and the scene of the notorious riots in 2004. Hookey painted this piece to show “how severe our subjugation is,” he says, “not only with the stealing of our land but also the demonisation of us by prominent media people” who “further subjugate the Aboriginal people and minorities.”

Gordon later teamed up with proppaNOW, a collective of outspoken urban-based Aboriginal artists from Queensland like Richard Bell and Vincent Ah-Kee, who pride themselves on creating visceral work that grabs media attention.

Demands for justice over land rights and structural discrimination are central themes. Part painting and part protest banners, their art is often emblazoned with bold slogans riddled with subversive word play.

Drawing on the work of George Orwell and the Black Panther Emory Douglas, Hookey views his art as a mirror on society. “My concerns are for the injustice,” Hookey tells us. “Every day we are totally bombarded with, you know, this propaganda; one way of thinking and looking.”

He aims not to correct the historical record but provide alternative perspectives that force you to question “your own reality.”

And the comments by van Diemen? “I think it’s fantastic,” Hookey says. “It’s great that she got that type of response too,” Hookey continues, “[…] it’s exposing this ugly element to the psyche that’s within this nation.

“A lot of the time the people that are viewing that do not like what they see,” he says. “Maybe what Annalise van Diemen said is a mirror too,” he speculates, “and people looked at that, and they saw themselves and they didn’t like what they saw at all.

“To me, that says more about them than it actually does about what she said.”

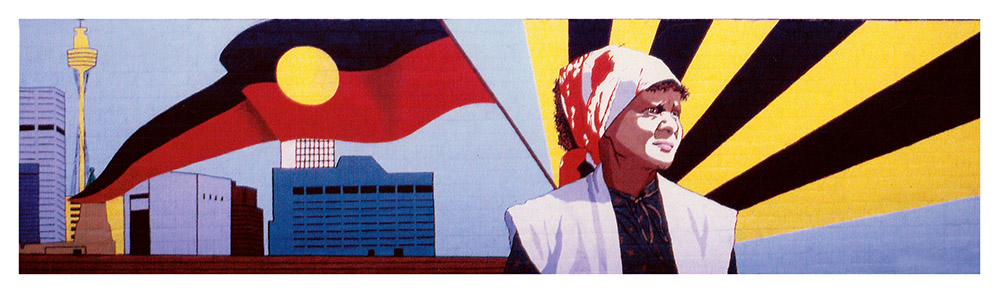

Get off the train at Redfern, the subject of Cognative frontier, and you’re confronted with a sprawling mural that emphasises the significance of the place to the Indigenous population. Indigenous artist Thea Perkins has deep connections to the area and helped restore the mural in 2018. She says the concept of a ‘cognative frontier’ is a “great way” to understand the division she still sees in Redfern and in our understanding of history.

“I am always kind of shocked,” she says, “[that] all those old attitudes that people have had, they still exist”. She argues artists “operate by going to war on that frontier”.

“You kind of let people come to their own conclusions about [a piece of work] and you can facilitate people to have that flip and understand something really foreign to them.”

The 40,000 Years mural in Redfern, Sydney depicting Aunty Mona Donnelly from the Aboriginal Medical Service. (Photograph by Carol Ruff.)

On the surface, the commemoration of the 250th anniversary of Cook’s landing was replete with outdated nationalistic concepts that Perkins describes as “confronting” and “erasing”. But the Australian National Maritime Museum at the centre of the commemorations hoped to use it as an opportunity to educate as well.

The museum received funding to gather Indigenous stories from the shore to balance the narrative. Indigenous artist Alison Page was tasked with travelling the East Coast to do just that. She paired the stories she heard with sections from Cook’s diary to create video works that offer new light on those early encounters.

“Every Aboriginal person who saw Captain Cook and his men thought they were ghosts,” Page explains. “We have these really crazy beliefs […] that when our ancestral totems die, so like a whale or something, the spirit goes over the ocean and comes back with white skin.

“Every Aboriginal person who saw Captain Cook and his men thought they were ghosts.”

“The first words that were said to Captain Cook by the two warriors at Kamay were ‘warra warra wai’. Cook says in his diary ‘all they wanted was for us to be gone’ so everyone thought the interpretation of those words was ‘go away’ but it wasn’t go away.

“‘Warra’ means dead, so they were saying ‘these people are dead’ and they were saying it to the mob that was in the bushes watching on.”

Cook attempted to interact with the Indigenous population by leaving them gifts. None were accepted. “Why would you take something off a dead person?,” Page says. “It might be bad magic, right?”

She says her work has given her a new appreciation for Cook. “By the time [he] sails away from Australia, he writes this entry in his diary which is amazing; he says, ‘although they may seem like the most wretched people on earth, the natives of New Holland’, as he called it, ‘are the happiest people I have ever witnessed. The land and sea provide them with everything they would ever need.’

“He got our values. He realised in 1770 what Australia is only just cottoning onto now about blackfellas, that they’ve sort of got it going on as far as happiness and non-materialism. And that was a man from Georgian England!”

“Cook realised in 1770 what Australia is only just cottoning onto now about blackfellas.”

Page describes these oral histories as “pieces of the puzzle that have been missing.” They’re important because they inform race relations today but they were only gathered for the anniversary.

The Morrisson government’s commemorative circumnavigation of Australia never happened due to the pandemic. That’s a good thing according to some, but John Longley who was supposed to captain the voyage disagrees.

A veteran of the America’s Cup, Longley found himself tasked with building a replica of the Endeavour for the bicentennial in 1988 and understands its significance.

“It was never a re-enactment voyage,” he says. “It was done to acknowledge an incredible man and the incredible work that Cook and his crew did. But secondly to make sure that we acknowledged and told the stories of the 60,000 year history.”

The 40,000 Years mural in Redfern, Sydney depicting Aunty Mona Donnelly from the Aboriginal Medical Service. (Photograph by Carol Ruff.)

When Cook landed at Gisborne in New Zealand, eight Māoris were killed by the British. When Longley returned in the replica 200 years later, the locals there threatened to set the ship on fire. But according to Longley, his arrival facilitated dialogue and reconciliation. “Storytelling is incredibly healing,” he says.

Sailing into Botany Bay would have sparked protest, but John Longley believes it would also have given an opportunity to express differences and correct misunderstandings.

Can you do that without the ship? “Of course you can,” says Longley. “But when the ship sails in […] it’s so powerful it demands a response.

“It’s such a difficult conversation to have,” he admits, “but that doesn’t mean you don’t do it.”

“It’s such a difficult conversation to have, but that doesn’t mean you don’t do it.”

Professor McKenna disagrees. In his view, this “symbolic reclaiming” is “an insult to Indigenous people” and an attempt to “create a national myth about Cook which really isn’t there.”

“It was a terrible idea,” he says.

The professor says we need to do better. “Until Aboriginal people are included in the nation’s parliament, its constitution, in its national capital in a major way, until we redress those big historical questions we’re going to go on like this.”

That requires conversation, and what has emerged from all of this is the role art continues to play in facilitating it. The question Page wants to focus on now is how to “bring the best of both of these cultures together to design a future for ourselves that is extremely successful and amazing.”

“If you draw on the legacy of Aboriginal agriculture, and architecture, and science and ecological land management, especially with the use of fire to manage the land properly, we’ve got it fucking going on,” she exclaims.

“If you draw on the legacy of Aboriginal agriculture, and architecture, and science and ecological land management, especially with the use of fire to manage the land properly, we’ve got it fucking going on.”

For Page, that future requires “honouring Aboriginal culture as central to the national identity” and having those values “written in the built environment, the ground we walk on, the paintings we see in galleries, the music we’re listening to, the books we’re reading.”

I offer these ideas to Hookey who professes a similar, if more assertive desire. One of his latest pieces features the phrase “we can’t settle for anything less than the total and absolute Aboriginaleyesation of so called Austrailya.”

“Aboriginaleyesation” means “looking at this country through our eyes,” encompassing the restoration of native place names and the adoption of native languages.

“A lot of it has to do with education,” Hookey explains, “it also has to do with interaction, sharing, learning, being open minded and shelving a whole lot of prejudices that people have been indoctrinated with.”

It’s utopian, Hookey acknowledges, and not something he thinks he will see in his lifetime, “but it’s something I think is achievable.”