This article was initially published in October, 2016. It appears here, in the wake of Chuck Berry’s death, with minor amendments.

The first time I met Chuck Berry he was playing a club called Where It’s At, which, in contradiction of its name, occupied the second floor of a drab business building in Kenmore Square and was operated by longtime Boston DJ Dave Maynard and his manager, Ruth Clenott. It was 1967, and I was in my senior year of college, working at the Paperback Booksmith, as I had for the last four years, both in and out of school. I was making $65 a week. The reason I know this is because Chuck Berry signed my paycheck.

Well, it wasn’t my paycheck exactly, it was my paycheck stub, and the reason he signed it was because I didn’t have anything else to present to him for an autograph. He had just given an exhilarating performance with a pick-up band of Berklee College students (unlike Bo Diddley, say, whom I had recently seen at the same club, Chuck Berry never carried his own band, and the result was inconsistent, to say the least). But tonight for whatever reason Chuck’s creative impulse had been stimulated, and rather than performing tired rehashes of his familiar hits with a rhythm section that didn’t have a clue, he followed what I’m sure was the unintended lead of the band, jazz players all, freely improvising on the hits, while throwing in unexpected bonuses like “Rockin’ at the Philharmonic” and Lionel Hampton’s “Flying Home,” along with a few T-Bone Walker and Louis Jordan tunes for good measure. He was clearly in good spirits, but it still took a while for me to work up the nerve to approach him as he stood to one side of the foot-high stage, packing up his guitar and getting ready to leave.

He regarded me with a quizzical look, casting an even more quizzical look at the book I was attempting to give him – “book” might actually be a little bit of a stretch for the pamphlet-sized booklet I was finally able to hand him, with its smudged white cover and stapled-together pages. What’s this? his noncommittal expression seemed to say, in a manner that betrayed neither receptiveness nor hostility. More to the point, that blank stare seemed to suggest, who the fuck are you? I have no idea what I said. I’m sure I wished that the book could simply declare itself. The stark black lettering on the cover announced “Almost Grown, and Other Stories, by Peter Guralnick,” and it had originally been published three years earlier, when I was 20. I must have mumbled something about how the book had been inspired in part by his music, that the title obviously came from his song, that I hoped he would like it. (Help me, I’m trying to paint a sympathetic picture here.) He flipped through the pages and placed the book carefully in his guitar case. “Cool,” he said, or the equivalent, and flashed me what I took to be an encouraging, if inescapably sardonic, smile. And then he was gone, off to the airport, off to another gig, or maybe just home to St. Louis. I still like to think that he read the stories on the plane on his way to his next destination.

It would be another 44 years before I actually met him.

But, first, perhaps I should say – well, you tell me, do I really have to say? – that there is no end to my admiration for Chuck Berry’s work, even if his commitment to performance has at times proved wanting. As much as Percy Mayfield remains the Poet Laureate of the Blues, Chuck Berry will always be the Poet Laureate of – what? Of Our Time. Has there ever been a more perfect pop song than “Nadine,” a catchier encapsulation of story line and wit in four verses and a chorus, in which the protagonist (like all of Chuck’s characters, a not-too-distant stand-in for its author but never precisely himself) is introduced “pushing through the crowd trying to get to where she’s at/I was campaign shouting like a Southern diplomat.” I mean, come on – and the song only gets better from there. When he was recognised in 2012 by PEN New England (a division of the international writers’ organisation) for its first “Song Lyrics of Literary Excellence” award, his co-honouree, Leonard Cohen, graciously declared that “all of us are footnotes to the words of Chuck Berry,” while Bob Dylan called him “the Shakespeare of rock & roll.”

Which is all very generically well. But perhaps the most persuasive tribute I ever encountered was delivered by the highly cerebral New Orleans singer, songwriter, arranger and pianist extraordinaire, Allen Toussaint. I was trying to get at some of the reasons for the dramatic expansion of his own songwriting aspirations (musically, poetically, politically) in the Seventies, when he graduated from brilliant pop cameos like “Ride Your Pony” and “Mother in Law” to more ambitious, post-Beatles, post-Miles, post–Civil Rights Era work. Was it the influence of Bob Dylan, say, that allowed him to contemplate a wider range of subjects, a greater length of songs? Oh, not at all, Allen replied in his cool, elegant manner; he wished he could agree with me, but his single greatest influence in terms of lyrics and storytelling from first to last was Chuck Berry. And with that he started quoting Chuck Berry lyrics, just as you or I might, just as Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, and Jerry Lee Lewis do on the fabled “Million Dollar Quartet” session. “What a wonderful little story that is,” he said of “You Never Can Tell,” Chuck’s fairy-tale picture of young love in Creole-speaking Louisiana, “how he lived that life with that couple, you know. Oh, the man’s a mountain,” said Allen unhesitatingly, and then went on to quote some more.

I saw Chuck in performance many times over the years, everywhere from Carnegie Hall to a decommissioned state armoury. I wrote to him at one point at the invitation of Bob Baldori, who started playing with Chuck in 1966 and has been close to him ever since. Chuck had begun work on his autobiography at that point, and Bob thought, a little fancifully perhaps, he might welcome some help. “Dear Mr. Berry,” I wrote in effect, “You won’t remember me, but …,” then cited Bob as a reference and suggested that while I didn’t know that I had anything to offer as a writer, maybe he could use me as someone to bounce ideas off, if he were so inclined. I never heard back from him, which was just as well, because when the book came out two years later, in 1987, it was a masterpiece. “It is at once witty, elegant, and revealing,” I wrote of it for Vibe, “and (or perhaps but) ultimately elusive. Every word was written by its author in a web of elegant, intricate connections that are both coded and transparent. Very much like the songs.” And it was all Chuck – with a little help from his editor, Michael Pietsch, who traveled to Chuck’s amusement park / residence, Berry Park, outside of St. Louis, to retrieve it.

It was not until New Orleans, in 2011, though, that I got beyond that first, monosyllabic exchange. We were both there to fulfil a date that was initially referred to without irony as “The Summit Meeting of Rock,” because it was to include filmed interviews with Chuck, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard and Fats Domino, both as a group and, in the case of the first three, singly as well. It was part of a Rolling Stone–sponsored oral history project for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame that had only recently begun, and I was the designated interviewer. Do I have to stipulate that it was one of the most challenging things I’ve ever done, and also, unquestionably, one of the most fun? You try facing down Jerry Lee Lewis, Richard or Chuck, each with his own keenly intelligent, widely divergent and informed point of view, and try to get a go-ahead smile out of them on their own uncompromising terrain. I think I’d be safe in saying that, overall, unaffected warmth and affection prevailed, stimulated as much as anything by everyone’s genuine love for Fats, but at the same time it was not an entirely smooth and mellow meeting. Religion, politics, personality – all of the usual sources of conflict were present in good measure. Little Richard at one point wanted to thank God for bringing them all to New Orleans, but Jerry Lee, an intensely religious man himself, demurred at what I think he took to be a too-casual appropriation of faith. “I don’t know about you,” he muttered, “but I came here on a plane. And I think you came by bus!” Someone suggested that Louis Jordan was one of the key figures in the development of rock & roll, and someone else objected that “Ain’t Nobody Here but Us Chickens” was not in their view anything like rock & roll. It was incredible! The interview with Jerry Lee was probably the most wide-ranging; Little Richard, for all of his avid study of history and precise recollection of it, was not about to abandon his theological texts; but it was Chuck who proved the most surprising, as, robbed of the constraint of memory, he abandoned, if only for a moment or two, his lifelong habit of emotional indirection and spoke unguardedly of his family, his mother and father, the expectations they had had of him and the inspiration with which they provided him, growing up.

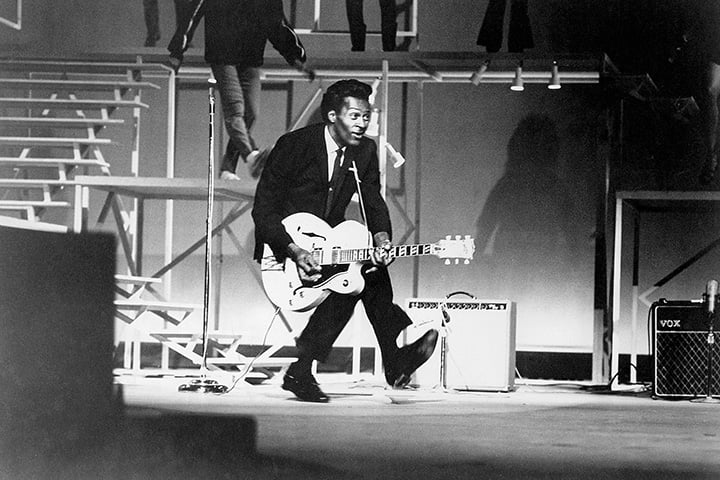

Chuck Berry in 2012

He was as slim and elegant as ever, wearing the jaunty captain’s hat that has become almost ubiquitous since the departure of most of his beautifully coiffed hair some years ago. Communication was sometimes a challenge, because not surprisingly he had left his hearing aids at home, despite the repeated reminders of his family and his friend Joe Edwards, proprietor of Blueberry Hill, the St. Louis club where he played off and on for almost 20 years before “taking a break” from performing two years ago. He spoke of poetry and politics (just to clarify, nearly everything is “politics” to Chuck, from the endemic chicanery of the music business to the endemic racism he has encountered over the years), and he insisted for the most part, just as he always has in his art, on speaking metaphorically, if unmistakably.

He spoke, too, of the sources of inspiration that he always points to for much of the flair, if not the full scope, of his creativity. (There is, Chuck will never fail to tell you, nothing new under the sun.) He cited Charlie Christian and T-Bone Walker and Louis Jordan (not to mention Louis Jordan’s great guitarist Carl Hogan: Check out “Ain’t That Just Like a Woman” if you want to hear one of the fundamental sources for Chuck Berry’s guitar style) – and Nat “King” Cole, too, for his diction. But as to his idea of reaching everyone, not just the “neighbourhood” (the ur-definition, of course, of rock & roll), well, that was something he derived from the concept of get-ahead capitalism that he got from helping out his father in the grocery business as a young boy. “By then,” he said, describing himself at ages 10 and 11, “I had a bit of politics in my head. My dad had a business of his own, selling groceries, and he worked for himself, so I came to handling money at that age. He carried vegetables in a basket and would go by someone’s door and knock on it. ‘Would you like …?’ You know, the material looked so good. [But] I sold a lot [of it] because of the ingenuity that I [showed] trying to sell.”

That was the very idea that he applied to the music, when, after driving up to Chicago to introduce himself to Leonard Chess on Muddy Waters’ recommendation, he introduced himself to the world at the age of 28 by employing that same sense of ingenuity, that same sense of “politics.” Meaning, he said, “M-O-N-E-Y. What sells. What’s on the market. Now I knew the market. There had to be a market in order for you to be successful in a business. The market had to need your business, or the product of it. So I tried to sing as though they would be interested, and that would become a market.” And then, he said, you multiplied that market, and you added another market to it, and it was as if you were still traveling from neighbourhood to neighbourhood, and pretty soon you had a constituency that included nearly everybody. That was the constituency that Chuck Berry was aiming for as an artist. And that was the constituency that he ultimately reached.

We started out our interview talking about poetry, and we came back to poetry in the end. Remember, this is a man whose older brother was named for Paul Laurence Dunbar, the great African-American poet, whose “We Wear the Mask” should be required reading in all the schools. It had always tickled me the way that Chuck would end so many of his concerts with a poem. It was a poem I had never heard in any other context, though it reminded me of “Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley, in which a traveler from “some antique land” stumbles upon the tomb of one of its ancient kings. “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair,” proclaim the words engraved on the faded stone at the base of the ruined monument, while “the lone and level sands stretch far away … boundless and bare.”

The poem that Chuck recited, while nowhere near as bleak (it takes a more positive, transcendental spin), was certainly in the same philosophical ballpark. It was called “Even This Shall Pass Away,” and, as I discovered from asking him about it, it was not an original poem by Chuck Berry at all; it was in fact a poem that he had first heard his father recite (“That’s my dad,” Chuck said. “I get a little choked up when I think of him”), when he was no more than six or seven years old. The poet, I would later learn after a little research (very little – it’s all over the Internet!), was Theodore Tilton, an American poet, newspaper editor, and Abolitionist, and the poem was first published in his collection The Sexton’s Tale in 1867. With very little prompting, Chuck recited the poem, and as he did, he got more and more choked up. “My dad,” he said, “was the cause of me being in show business. He was not only in poetry but in acting a bit. He was Mordecai in the play A Dream of Queen Esther. [This was a church production by a prolific white playwright and meteorologist, Walter Ben Hare.] He was very low in speech and music, and he came out onstage, he came out to tell the king, ‘Sire, sire, someone is approaching our castle.’ And I knew his voice. I’m five years old right now. I knew his voice and I hollered out in the theatre, ‘Daddy!’ I don’t remember it, but they tell me I did. His position in the choir was bass. Mother’s was soprano and lead. That’s all there was in our house, poetry and choir rehearsal and duets and so forth; I listened to Dad and Mother discuss things about poetry and delivery and voice and diction – I don’t think anyone could know how much it really means.” Who were some of his favourite poets as a kid? I ask. Edgar Allen Poe, he said after some consideration (“I can’t think of them [all], my memory’s really bad”), and Paul Laurence Dunbar was his mother’s. On second thought, he offered, Dunbar was his favourite, too.

But getting back to that recitation – he couldn’t do it as well as his father, Chuck said after completing several verses of “Even This Shall Pass Away,” “my dad’s voice rang. But here’s something for you.” And with that he launched into the fifth verse (out of seven), searching for the words, searching for the memories, concluding triumphantly, “‘Pain is hard to bear,’ he cried. ‘But with patience day by day/Even this shall pass away.’ Oh, I’m breaking up again.” And with that he concluded, to the applause of everyone in the room, the film director, the sound and camera man, his son, Charles Jr., a woman who carried a card “Sherry with Berry,” and assorted other bystanders – no more than 25 or 30 in all. He was in tears. He was in triumph.

Chuck Berry was not like any other popular performer that I can think of (oh, Merle Haggard might be a distant cousin, even a second or third cousin once removed, but no closer). For all of the canny “political” (read “artistic” here) inclusiveness that established both his career and his legacy, he has from the beginning chosen to set himself apart. Or been set apart. By a juvenile conviction for armed robbery before he ever thought of entering show business (remember: this was an upwardly mobile, middle-class kid, by his own description). Later by two mid-career prison terms, one coming at the height of his success in 1960 (a contested Mann Act violation, which could certainly be seen as a form of “political” [read “racial” here] reprisal). Not to mention some of his well-documented sexual proclivities and peccadillos (and I don’t mean to minimise them here), what his biographer, Bruce Pegg, writes, represent the actions of “a man whose detachment from society made him feel immune to its mores and taboos.” (For details see Pegg’s Brown Eyed Handsome Man: The Life and Hard Times of Chuck Berry.) Sometimes that sense of detachment has served him well (by allowing him to speak in another person’s voice for example, in his songwriting), sometimes it has not – but it has always been a non-negotiable part of his personality. And it has at times alienated his own audience at the very times that, were he but able to admit it, he might have needed them most.

Which tended to make his transition to loveable icon, to venerable (and much-venerated) elder statesman, a little daunting at times. In his final few years he enjoyed a round of gracious honours: a larger-than-life duckwalking statue in St Louis; that PEN New England “Literary Excellence in Song Lyrics” award, held at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, where Chuck was delighted to snap pictures, and have his picture taken with images of JFK; his celebration in a week-long series of events as an American Music Master at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame; the $100,000 international Polar Music Prize, which has often been referred to as “the Nobel Prize for Music.” At each of the first three (he was not able to attend the Polar Prize ceremony in Sweden in 2014), he acquitted himself with more than a hint of sentiment and a large dose of his own brand of idiosyncratic charm. “I’m wondering about my future,” he told Rolling Stone reporter Patrick Doyle. When pressed to be a little more explicit, “I’ll give you a little piece of poetry,” he said. “Give you a song?/I can’t do that/My singing days have passed/My voice is gone, my throat is worn/And my lungs are going fast.” Or as he put it 10 years earlier, in 2002, “In a way, I feel it might be ill-mannered to try and top myself. The music I play is a ritual. Something that matters to people in a special way. I wouldn’t want to interfere with that.”