In the long, tedious hours between soundcheck and showtime, Brian Wilson likes to park himself at the side of the stage, hidden behind the curtains, in an oversize black chair. The chair has traveled with him from Tokyo to Tel Aviv and back home to the Pantages Theater in Hollywood tonight. Dressed in a lavender button-down, sweatpants and white Nikes, Wilson sits impassively atop his faux-leather throne, munching sushi rolls as the pre-show noise and bustle swirl around him.

When a concert promoter or VIP guest wanders over to say hi, Wilson often shuts his eyes and pretends he’s asleep. After 56 years as a Beach Boy, he admits the buildup to a concert can still be “a total mindfuck,” filled with worry and self-doubt. So he likes to disappear into what he calls “the Zone,” where he can meditate, beat back the nerves and maybe pray a little. “I feel things out, catch vibrations from my band and the crew,” he says. “I get real nervous, then I tell myself, ‘Not nervous, Wilson! Confident!'”

At 75, Wilson is in the middle of a highly improbable, wildly successful late-career roll. Since launching this tour in 2016 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Beach Boys’ landmark Pet Sounds album, Wilson has performed 165 shows in 24 countries, with more dates being added into 2018. It’s a grueling, time-zone-shattering run that would punish the most disciplined performer, let alone a reclusive senior citizen suffering from a serious psychiatric disorder and back pain, not to mention a career-long aversion to performing.

And it might have never happened. Before this tour, Wilson’s stellar, devoted touring band had lost a key member, ticket sales had diminished, and Wilson told me he was worn out and that retirement wasn’t far off. But then something changed. The 2015 biopic Love & Mercy sparked new interest in rock’s tormented genius, and sometime in the winter of 2016 Wilson noticed that his usual post-holiday depression had vanished. “The clouds lifted,” he says. “It was a blessing.” Wilson also worries about how long his voice and his body can hold up on the road, and he may be motivated by fear to keep going while he can.

Joined by original Beach Boy Al Jardine and Jardine’s son, Matt (who nails the high parts Wilson sang in the Sixties, and takes the lead on “Don’t Worry Baby,” among other songs), along with the great Blondie Chaplin on guitar and vocals, Wilson and his band have found a looser, harder edge onstage. At two epic concerts at the Pantages in May, Wilson led the 10-piece ensemble through a live version of Pet Sounds, plus 25 Beach Boys hits and songs Wilson picked from the lesser-known corners of his catalog. Wilson’s singing was rough at times, but he drove the band with emotion and an eccentric sense of humor – he looked like he was actually having fun up there.

“I honestly don’t know what happened,” Wilson says in his dressing room, with a shrug and a soft smile. “I thought I was gonna hang it up. But then I changed my mind. I said, ‘What am I gonna do? Sit around and watch TV? No way!’ Nothin’ was really happening back in L.A., so I figured I might as well go tour. I just said, ‘Well, fuck it, I might as well get off my ass and tour.’ So I got off my ass and toured.”

As we talk, Wilson eats sushi piled onto a plastic takeout lid resting on his lap. He pops the last piece of tuna and flips the lid across the room, missing the garbage can by several feet. “I’m old!” he half-shouts. “I’m an old man, and I have to think to myself, ‘What the fuck am I gonna do about this?’ Nothing you can do about getting old. When I look in the mirror, I don’t like what I see. But then I think about it, and I think about Paul touring, Mick and Keith are still touring, so are [fellow Beach Boys] Mike and Bruce. You know, I’m getting older but I don’t give a goddamn. I can still sing my ass off. I’m only 74. [He turned 75 a month later, on June 20th.] Which is a fucked age, but I don’t mind it. When I sing onstage, I ain’t 74. I sound like a 30-year-old! That feels good. I get a little break from being 74.

“I look old, but I sing young,” he continues. “Who would have thought? I’ll tell you who: nobody.”

Two hours before showtime, the backstage area is crowded with family, including six of Wilson’s seven multigenerational kids, old friends and music-biz acquaintances. Brian is in a garrulous if offbeat mood. When an old buddy, Peter Leinheiser, approaches, Wilson blurts, “How’s your sex life, man?”

Leinheiser sputters, “I ride a bicycle – it’s hard to pick up women on a bike.”

“Oh,” Wilson says, adding, “Well, you look good. If you were a chick – I don’t know what I’d do!”

“I haven’t written a song in five years,” Wilson says, then lets out two Donald Duck–like quacks. “All outta tunes. But I think I’m getting ready to write.”

Al Jardine, the only other original Beach Boy in the band, pulls up a chair to check in with the boss. “Hey, it’s Al Hard-On,” Wilson says, deadpan, a joke he’s probably been making since the two were kids growing up in Hawthorne, California. Jardine, whose radiant tenor is nearly as strong today as when he sang lead on “Help Me, Rhonda” in 1965, is a gentle, generous presence on tour – it’s easy to tell Wilson enjoys being around him. “How ya holdin’ up, Alan?” Wilson asks. “Well, I’m tired, but I’m happy,” Jardine says, in his white wide-lapel suit, the same style he’s worn onstage since the Seventies. “You know how we do it, grind it till you get through it.”

Wilson nods, and says that phrase reminds him of a song – “It’s O.K.,” from the Beach Boys’ 1976 album 15 Big Ones.

“Oh, right,” says Jardine. “Remind me of that one?”

Wilson starts to sing the chorus, and Jardine chimes in:

Gotta go to it

Gonna go through it

Gotta get with it

When Wilson and his cousin Mike Love wrote that song, it was a rallying cry for the Beach Boys’ comeback, a decade after their last big hit, at a time when Wilson was wrestling with drug addiction and the band was mired in dysfunction. “I still believe in that message – working hard is the way to go,” Wilson says tonight. “I live by it.”

“Yeah, I guess me too,” says Jardine.

“Alan, I’m so proud of you,” Wilson says. “Your voice is a natural wonder. We’ve been through a lot, and look at us, we’re still here and we’re still kicking ass. I love you, man.”

“Well, thank you, Brian, it’s all because of you. I love you too.”

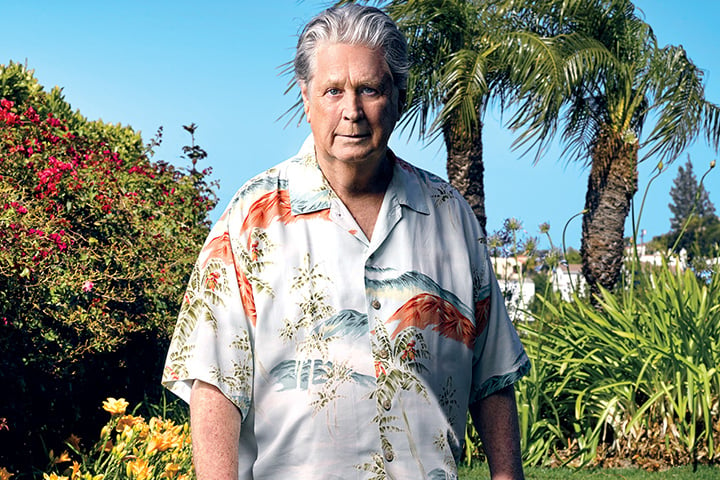

Onstage in August. Credit: Robyn Pope/Newscom

The afternoon before his second L.A. show, Wilson sits in a corner booth at his favorite Beverly Hills deli, with a Cobb salad and a vanilla malt. “I miss this place,” he says. “There’s nowhere like home. But for me, there’s nowhere like the road. Retire? No way. Hell, no. Fuck, no. Not a chance! Gotta keep going. I love my band, I love my bus, I love my life. I miss the deli, but I can deal with it.”

Wilson looks relaxed, in a pink polo with his sandy-silver hair slicked back. He complains that it’s hard to keep on a diet on tour, and that he’s not exercising enough. He asks what I do for exercise, and I tell him I play tennis and lift (very light) weights. “Really?” he asks. “Like your pectoralis? Are you building up your tits?

“I’ll give you some advice,” he goes on. “If you want to add a little definition to your chest, lay on a bench and” – mimicking a bench-press motion – “lift the barbell, from here to here, it really works. Start building up, you can see the difference when you look in the mirror, like, ‘Hey! I got my pectoralis working!’ That’s what I did! In 1990, I was in really good shape.”

In September, he’ll release a retrospective of his solo work, with two new songs, and he’s already planning his next moves: He wants to tour China for the first time; record an album of his favorite rock & roll covers; and says he’d love to host his own radio show, dedicated to the music of Phil Spector.

“To succeed in life, you have to put a little muscle into it – mind muscle,” he says. “Not sure where that comes from, but I’ve got it. I’m success-oriented. You have to program yourself to be successful. Kick ass at life.”

It’s a month before his 75th birthday, and he seems awed by the milestone. “Goddamn, 75,” he says. “Motherfuckin’ 75. I can’t believe it.” He says this not with dread but a kind of wonder, like a child who one day woke up an old man. In the past, a big birthday might have thrown him into a tailspin, he admits, but “I don’t have valleys or peaks anymore. I don’t get too high or too low. It’s been a long time since I’ve had serious depression, or elation. Mostly I’m just pleasantly depressed.”

He recalls an afternoon a year ago, the day after his 74th birthday, when he and I drove through New York’s Central Park to visit a building where George Gershwin once lived. “I’ll be goddamned if we didn’t get to see where Gershwin lived!” Wilson says. “The vibes were fantastic. I felt his presence. Shit, yes, I did, absolutely.

“For me, Gershwin is huge,” Wilson says. “My first music hero. I listened to his goddamn music when I was three years old! ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ blew my three-year-old mind! He was 26 when he wrote it. It was like nothing that came before.

“There’s no joking around when it comes to Gershwin,” he continues. “His music is too great. It makes me feel wonderful, warm, spiritual, the feeling of love – all those great trips are where it takes me.”

I mention that Wilson was 23 when he started Pet Sounds – three years younger than Gershwin when he wrote “Rhapsody.”

“What can you say about Pet Sounds?” he says with a slight, embarrassed laugh. “It’s a great album, I know, but there are more rock & roll albums than Pet Sounds. Pet Sounds is more of a – uh, what would you call it? It’s kind of an introspective, kind of spiritual record.”

Brian Wilson with Mike Love in 1966. Credit: © Capitol Photo Archive

Wilson has a complicated relationship with his masterwork – he’s self-conscious about the young man’s anguish in his lyrics, and his falsetto singing. And even though Pet Sounds has become one of the most celebrated albums in rock history, in 1966 it was a commercial dud that exposed an irreparable rift between Wilson and his band. While Love wanted to keep cranking out pop songs about girls and the beach, Wilson was heading into more turbulent terrain.

The group never quite recovered from that schism, even when its surviving members reunited for a 50th-anniversary tour in 2012. That tour ended when Love opted to continue on the road with his own band rather than extend the reunion with his cousin beyond the 75 dates, causing Wilson to write an L.A. Times op-ed headlined “It Kinda Feels Like Getting Fired.” The two haven’t spoken in the past five years. Asked if he can imagine the original group reuniting again, Wilson said, “The Beach Boys might get together again – but not with me.”

“[Pet Sounds] brings back a lot of memories, mostly good,” Wilson says, “but it throws me off balance. I miss my brothers, I miss hearing Carl sing, and I miss my dad so much, even though he died in 1973. It takes me back to those places, and it’s very emotional.”

Wilson says he has trouble relating to his younger self. “I feel like the same guy, but I’m not the same guy,” he says. “I have the same love in my heart as when I was a kid, but I’m older, been through a lot. I’ll sit there and be like, ‘I’m a man! I’m a man!’ It’s a heavy trip to try and get into my 23-year-old brain.”

“I don’t have valleys or peaks anymore. I don’t get too high or too low. Mostly I’m just pleasantly depressed.”

Wilson’s musical director, Paul Von Mertens, says that during the Pet Sounds set Wilson will often mess around with vocal phrases. “He doesn’t want to be that 75-year-old in board shorts and flip-flops,” Von Mertens says. “He wants to sing the songs how he feels them now.”

At the Pantages, Pet Sounds did not appear to be Wilson’s favorite part of the show. He seemed distracted at times, rushing through passages and chopping vocal lines in jarring ways. Both nights, he bolted from the stage a minute before the end of the last song, “Caroline, No,” so that by the time Pet Sounds came to its majestic finale, with the recorded sound of a train whistle and Wilson’s own barking dogs, the maestro was back in his chair, chugging a Diet Dr Pepper.

I remind Wilson that Pet Sounds means as much to generations of Beach Boys fans as “Rhapsody in Blue” means to him: “I feel the love, some of it. But, you know, I wonder if people really like me or not – if they like me as a performer. I don’t know who the hell likes me and who doesn’t. I want to believe my music helps people on a spiritual level, helps them with their troubles, eases their minds, makes them feel love. But in the end, how can I know?”

With (from left) daughter Daria, son Dash, wife Melinda. Credit: Jason Fine for Rolling Stone

The next afternoon, we are rolling north on Highway 101 in Wilson’s sleek new blacked-out tour bus, headed for Santa Barbara. His three youngest kids – Dylan, 13, Dash, 8, and seven-year-old Dakota – are along for the ride, eating Oreos and playing with their fidget-spinners in the front lounge as the bus moves through the kind of California landscape Wilson has mythologized in so many songs – rugged mountains dipping into the blue Pacific, wind-sculpted beaches, surfers and a school of dolphins bobbing in the chop.

If Wilson notices any of this, he doesn’t let on. He’s sitting next to the driver, his white Nikes propped on the dash and his eyes closed for most of the ride. He says he’s tired from four shows in seven days, looking forward to two weeks off before heading to Hawaii, then Europe. “I miss my family,” he admits. “Any good family time you can get, you should take it. It’s worth all the pain and confusion and bullshit you go through, just to get those moments. But I don’t want to sit around longer than I have to – I want to be out there.”

He admits the old vise grip of depression can still get him. “I got through a pretty rough night. I had a hell of a time,” he says. “I was scared of dying and going through all kinds of shit, and a song got me through it. You know Danny Hutton’s [Three Dog Night] song ‘Black & White’? If you ever get in a pinch, boot up ‘Black & White’ on your cellphone. You’ll feel better right away.

“It’s like, Elton John had that song ‘Someone Saved My Life Tonight,’ and that’s exactly what happened to me. Someone saved my life. I thought I was dying. But nothing was going on, I just got into a mental thing. But I got through it!”

At the Santa Barbara Bowl, set into a lush hillside overlooking the ocean, a lavish barbecue is set up for the band backstage. Wilson seems pensive, and prefers to eat on his own, in his chair by the side of the stage with his kids gathered around him. We sit in silence for a while, and I sense it’s time to give him space to get into the Zone before the show.

As I say goodbye, Wilson holds onto my hand for several seconds, then leans over and kisses it. “I hope I give a good show tonight,” he says quietly. “And I hope I go to heaven.”

—

Main photo by Mark Selger.

This article features in issue #792 (November, 2017), available now.