Charlie Daniels, who died Monday of a stroke at 83, was best known for his manic fiddle playing, his kinship with Seventies Southern rockers, and hits like “Uneasy Rider” and “The Devil Went Down to Georgia.” But over the course of his five-plus-decades career, Daniels also intersected with many non-Southern rockers, especially early on; he contributed to the Bob Dylan albums New Morning and Self-Portrait, was a member of Leonard Cohen’s touring band, and produced Elephant Mountain by the Youngbloods (home to two of their best songs, “Sunlight” and “Darkness, Darkness”).

In 1970, a period when he was making his living as a session musician, Daniels had the unique opportunity of working with both George Harrison and Ringo Starr right after the Beatles broke up: Daniels played bass during an impromptu studio session with Harrison and Dylan, then was recruited to strum along on Starr’s country album, Beaucoups of Blues. Daniels and I talked about this during a 2009 interview for my book Fire and Rain: The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, CSNY, James Taylor and the Lost Story of 1970, but here is the expanded, never-published version of his comments.

I was on tour with Leonard Cohen in 1970, and we were going to Amsterdam. The rest of the band had gone ahead, but [producer] Bob Johnston and I had stopped in New York for the night and were leaving the next day. I can’t remember what we stopped for. We had a day off and Johnston called me and said, “You want to come down here and play bass with Bob Dylan and George Harrison?”

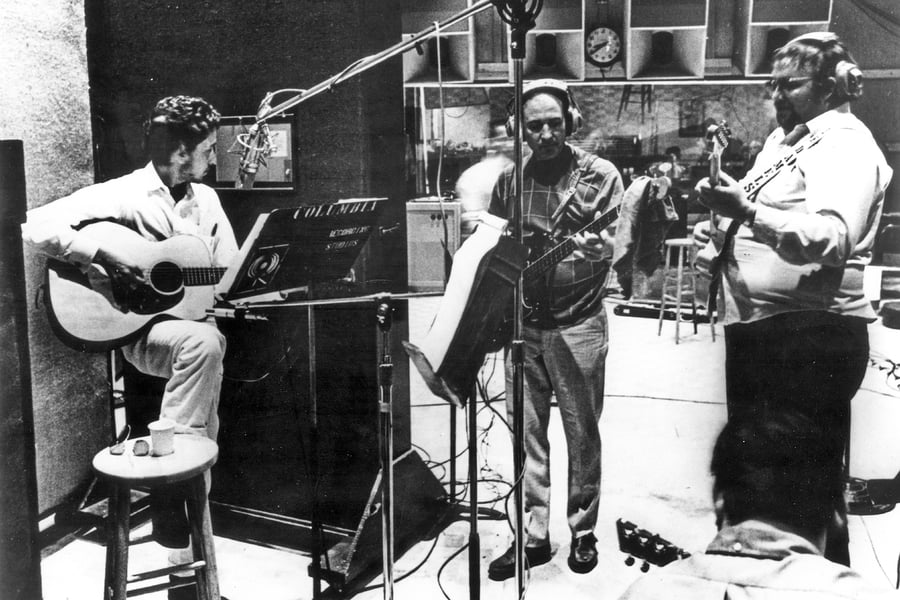

We went to the Columbia studio in New York, and it was just the four of us — George, Bob, me, and Russ Kunkel on drums. And Johnston and an engineer in the control room. I don’t remember anyone else even dropping by. I was playing bass, maybe a bit of guitar. I had never met George before, but he was a really nice, humble guy. He had long hair and a beard and blue jeans. He could be dapper at times, but this was during his hippie-look years. There was a great mutual respect between Bob and George.

George didn’t have a green card or work permit or whatever it is you have to have, so they couldn’t call it an official session and release the stuff. It was basically a jam session. I have no idea how many songs we did. It was just a day of jamming. We turned the tape machines on and just went for it. It was four people in the studio playing music and having a good time. No pressure, no hurry. Very relaxed, which is something you usually don’t equate with being in a recording studio. We could’ve been sitting on a rocking chair on a porch in West Virginia.

“I was playing bass and at one point George said to me, ‘You want to be a Beatle?’”

Bob was singing anything you wanted. It was, “How about ‘Gates of Eden?’” He couldn’t remember the words to all of them. He also did some of the stuff that ended up on New Morning, but not those versions. You could tell George was a Carl Perkins fan, and I do remember us playing “Matchbox.” Some of those songs, like “Cupid,” may not even be complete.

I was playing bass and at one point George said to me, “You want to be a Beatle?” Of course, it was in a facetious sort of way. He was just making a joke. He wasn’t the guy who broke the band up, by a long shot. I have no way of proving this, but I bet from the kind of guy he was, I would think he was the one who was most sorry it broke up.

During the course of the day, George asked me who played steel guitar on Bob’s stuff and I said, “Pete Drake.” He said, “I’m fixing to go do an album and I’d like to use him,” and I said, “Give me your contact information and I’ll pass it along.” Which I did. Pete ended up going over [to the U.K.] and played on George’s album [All Things Must Pass]. And while he was there, Ringo said he was interested in doing a country album.

When I was back in Nashville, they called and asked me to come around for the Ringo album. Maybe it was Pete’s way of paying me back! It was the first time I met Ringo. He seemed like a regular guy with a sense of humor. I didn’t have that much contact with him. There’s a picture of us on the back of the album. Me and the beginnings of my beard. That was the longest time we spent with him. We just walked out next door to the vacant lot next to the studio and took the picture. It was not a tight-security situation. I’ve been in high-security situations, but I didn’t see it there.

It was a very straight-ahead Nashville session and didn’t take long. I played rhythm guitar. Three cuts per three hours, and in three or four days we had the recording done. These were working sessions. It was like working with anybody else in Nashville, with the producer watching the clock. It was, “Ringo, we’re happy to have you in town. We’re honored to be at the session. Now let’s work.” There was nothing as relaxed as the stuff we did with Bob and George. This was the total opposite. It was probably the cheapest album Ringo ever made.

You couldn’t ignore this was a Beatle, one of the biggest bands at the time. It was good for the image of Nashville. But the [musicians] were not so overwhelmed, by any stretch of the imagination. These guys are used to working with stars. Maybe not someone with the magnitude of a Beatle, but these guys aren’t starstruck. They go in and record and everyone’s happy to be included on the sessions. I know I was.

I have to be honest: I’m a fan of Marty Robbins. I thought it was a great and admirable thing and very good for country music for Ringo to be doing it. He’s not the top country singer I’ve ever heard by any stretch of the imagination. But I thought he did an adequate job. I admire a guy who’s got a lot of variety recording wise. I think George and Ringo were kind of finding themselves, especially in retrospect, after seeing the Let It Be movie.