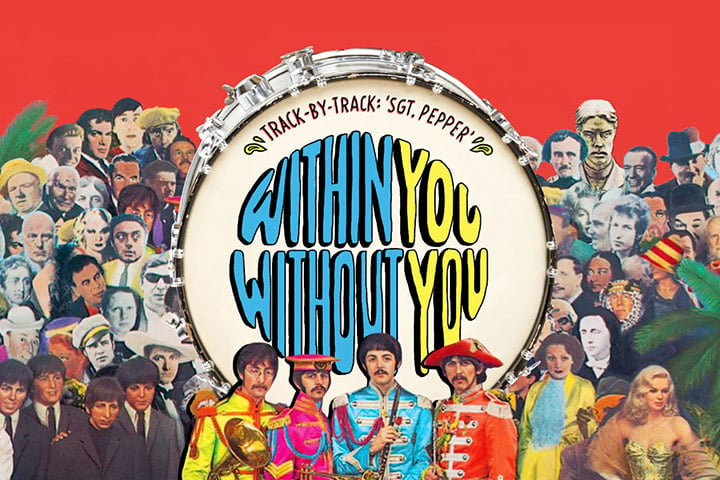

The Beatles‘ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which Rolling Stone named as the best album of all time, turns 50 on June 1st. In honour of the anniversary, and coinciding with a new deluxe reissue of Sgt. Pepper, we present a series of in-depth pieces – one for each of the album’s tracks, excluding the brief “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” reprise on Side Two – that explore the background of this revolutionary and beloved record. Today’s instalment tells the story of George Harrison’s Indian-influenced late addition to the record, “Within You Without You.”

“I don’t personally enjoy being a Beatle anymore,” George Harrison admitted to biographer Hunter Davies not long after the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967. For all the praise it garnered, the recording was fraught with growing pains for the band’s youngest member, who had turned 24 that February. “All that sort of Beatle thing is trivial and unimportant. I’m fed up with all this ‘me, us, I’ stuff and all the meaningless things we do. I’m trying to work out solutions to the more important things in life.”

As Harrison grappled with the big questions, the tedious piecemeal process that defined the band’s recent sessions grated on him. “Up to that time, we had recorded more like a band; we would learn the songs and then play them,” he explained in the Beatles Anthology documentary. “Sgt. Pepper was the one album where things were done a little differently. A lot of the time it was just Paul playing the piano and Ringo keeping the tempo and we weren’t allowed to play as a band so much. It became an assembly process – just little parts and then overdubbing – and for me it became a bit tiring and a bit boring. I had a few moments in there that I enjoyed, but generally I didn’t really enjoy making that album much.” Making matters worse, Harrison’s initial contribution, a psychedelic swirl of cynicism called “Only a Northern Song,” was met with a response that fell somewhere between apathy and contempt.

Harrison had flourished during the three-month break that preceded the Sgt. Pepper sessions, a well-needed respite after the traumatic 1966 world tour that ended their live career for good. Accompanied by his wife Pattie, he flew to India that September for six weeks, checking into Mumbai’s Taj Mahal Palace Hotel under the name Sam Wells. The main objective of the visit was to study under sitar virtuoso Ravi Shankar. Many players believe the instrument takes several lifetimes to master, so Harrison had to settle for a crash course. “I had George practice all the correct positions of sitting and some of the basic exercises,” Shankar wrote in his autobiography, My Music, My Life. “This was the most one could do in six weeks, considering that a disciple usually spends years learning these basics.” The posture was rough on Harrison’s hips, so Shankar signed him up for additional yoga courses.

It didn’t take long for news to spread that a Beatle was in Mumbai, and a reluctant press conference did little to discourage reporters who dogged the Harrisons wherever they went. They soon left the city to travel throughout the countryside, ultimately residing on a houseboat on Dal Lake in the northern territory Kashmir, at the foot of the Himalayas. Shankar, in his role as mentor, suggested that Harrison grow a moustache to disguise himself. Though it would take more than that to camouflage one of the most famous faces in the world, the change in appearance offered an important psychic break from his mop-topped identity. Exploring on his own, senses bombarded with exotic sights, sounds, smells and tastes, he felt free. “It was the first feeling I’d ever had of being liberated from being a Beatle,” he recalled.

The journey had a profound effect on Harrison, opening the floodgates of his spiritual consciousness and emboldening his curiosity. “The religions they have in India, I just believe in them much more than anything I learned from Christianity,” he said in an interview with the BBC Radio’s World Service network during his stay. “The difference over here is that their religion is every second and every minute of their lives and it is them – how they act, and how they conduct themselves and how they think.” His recent experiments with psychedelics had offered a glimpse of the divine, but now he sought an innate path to a higher power. “After I had taken LSD a lingering thought stayed with me and that thought was ‘the yogis of the Himalayas,'” he explained years later. “I don’t know why it stuck. I had never thought about them before, but suddenly this thought was at the back of my consciousness … that was part of the reason I went to India. Ravi and the sitar were excuses. Although they were a very important part of it, it was a search for a spiritual connection.” The connection he found would remain a constant for the rest of his life.

By the time he returned to England on October 22nd, he was reborn – and returning to the limitations of life as a Beatle in the stuffy institutional gloom of EMI’s Abbey Road Studios was not what he had in mind. “It was a job, like doing something I didn’t really want to do, and I was losing interest in being ‘fab’ at that point,” he reflected in the Anthology documentary. “I’d been let out of the confines of the group, and it was difficult for me to come back into the sessions. In a way it felt like going backwards.”

His resentment spilled over into his music. Returning to the theme of financial injustice, which had served him so well on Revolver‘s “Taxman” a year earlier, Harrison took aim at the Beatles’ publishing company, Northern Songs. Originally a venture for Lennon and McCartney’s music, managing director Dick James had persuaded Harrison to sign on soon after he began composing. The drawbacks of the deal quickly became apparent, especially after the company became publicly traded in February 1965. McCartney and Lennon, as the main songwriters, were named majority shareholders, each taking 15 percent (750,000 shares), while Harrison and Ringo Starr reportedly each held .8 percent (40,000 shares). This meant that Harrison did not own the copyrights to his own music, and that Lennon and McCartney – plus other shareholders – earned more from his songs than he did.

Harrison channeled his frustrations into “Only a Northern Song.” It can be viewed as the Beatles’ first meta-musical experiment, as he frets about his own chords, words and harmony, but in the end realizes that it doesn’t matter because “it’s only a Northern Song.”

“It was at the point that I realized Dick James had conned me out of the copyrights for my own songs by offering to become my publisher,” Harrison explained to Billboard in 1999. “As an 18- or 19-year-old kid, I thought, ‘Great, somebody’s gonna publish my songs!’ But he never said, ‘And incidentally, when you sign this document here, you’re assigning me the ownership of the songs,’ which is what it is. It was just a blatant theft. By the time I realized what had happened, when they were going public and making all this money out of this catalog, I wrote ‘Only a Northern Song’ as what we call a ‘piss-take,’ just to have a joke about it.”

The other Beatles were less than amused when they gathered in the studio on February 13th, 1967. Producer George Martin particularly disliked the song, later writing that he “groaned inside” when he heard it, and deeming it “the song I hated most of all” in the entire Harrison oeuvre. Engineer Geoff Emerick shared Martin’s opinion, describing it in his memoir, Here There and Everywhere: Recording the Music of the Beatles, as “a weak track that we all winced at,” with “musical content that seemed to go nowhere. What’s more, the lyrics seemed to reflect both his creative frustration and his annoyance with the way the pie was being sliced financially. It seemed like such a inappropriate song to bring to what was generally a happy, upbeat album.”

They spent two days working on the song, yet it failed to take flight. “The Beatles were clearly underwhelmed,” writes Emerick. “John was so uninspired, in fact, that he decided not to participate in the backing track at all. Still, Paul, Ringo and George ambled through quite a few takes of ‘Only a Northern Song.’ It took a long time because nobody could really get into it, not even George himself. I think he was actually a bit embarrassed about the song – his guitar playing had no attitude, as if he didn’t care.”

The indifference of his bandmates sank what little enthusiasm Harrison had. Quite literally a junior partner in a business sense, he felt equally belittled in the studio. “In general, sessions where we did a George Harrison song were approached differently,” writes Emerick. “Everybody would relax – there was a definite sense that it really didn’t matter. It was never said in so many words, but there was a feeling that his songs simply didn’t have the integrity of John’s or Paul’s – certainly they were never considered as singles – and so no one was prepared to expend very much time or effort on them.” This attitude did little to improve Harrison’s cool feelings towards the band.

The second night of sessions ended early, and it fell to Martin to deliver the bad news. “I had to tell George that, as far as Pepper was concerned, I did not think his song would be good enough for what was shaping up as a really strong album,” he remembered. “I suggested he come up with something a bit better.”

Several weeks later, he did. In early March, Harrison attended a dinner party at the home of Klaus Voormann, a German musician and artist who had been a friend to the Beatles since their days playing Hamburg’s Reeperbahn district in the early Sixties. Tony King, another comrade and future Apple executive, was also present, and recalled the far-out dinner talk in Steve Turner’s book, A Hard Day’s Write: “We were all on about the wall of illusion and the love that flowed between us, but none of us knew what we were talking about. We all developed these groovy voices. It was a bit ridiculous, really. It was as if we were sages all of a sudden. We felt we had glimpsed the meaning of the universe.”

“The tune struck me as being a little bit of a dirge, but I found what George wanted to do with the song fascinating.” – George Martin

Later in the evening, Harrison began playing Voormann’s pedal harmonium. A melody started to take shape, with words taken from their earlier conversation. “I was doodling on it when the tune started to come,” Harrison told Davies. “The first sentence came out of what we’d been doing that evening … ‘We were talking.’ That’s as far as I got that night. I finished the rest of the words later at home.” He called the song “Within You Without You.”

The tune was partially based on a lengthy suite Shankar had written for All-India Radio. “It was a very long piece – maybe thirty or forty minutes – and was written in different parts, with a progression in each,” Harrison explained during the Anthology. “I wrote a mini version of it, using sounds similar to those I’d discovered in his piece. I recorded in three segments and spliced them together later.” The music showcased Indian modes and textures within the familiar framework of a Western pop song, and the lyrics were a similar blend of cultures. The desire to diminish one’s ego and remove the illusionary “space between us all” is a tenant of Hinduism, whereas references to those who “gain the world and lose their soul” are taken from several warnings Christ made to his disciples in the Gospels of Matthew and Mark.

“Within You Without You” was warmly received when Harrison presented the song to Martin. “It was a bit of a relief all around,” the producer wrote. “The tune struck me as being a little bit of a dirge, but I found what George wanted to do with the song fascinating.” Unable to find full-time Indian session musicians for hire, the two Georges called upon members of London’s Asian Music Circle. “They have jobs like bus driving during the day and only play in the evening,” Harrison explained to Davies. “[But] they were much better than any Western musician could do, because it at least is their natural style.” To set the mood, the floor of EMI’s Studio Two was covered with woven carpets. Lights were appropriately dimmed and joss sticks lit.

Martin, who augmented the song with an ingenious string score using Western instruments, was unable to read Indian music. Instead, Harrison walked around to each member of the Music Circle and taught them their parts using the traditional notation and syllables. It was a power shift Harrison no doubt savoUred; for the first time, he was in total command of his own session.

Though he was the only Beatle on the track, his bandmates praised “Within You Without You.” “I think that is one of George’s best songs, one of my favorites of his,” Lennon later said. “I like the arrangement, the sound and the words. He is clear on that song. You can hear his mind is clear and his music is clear. It’s his innate talent that comes through on that song, that brought that song together.”