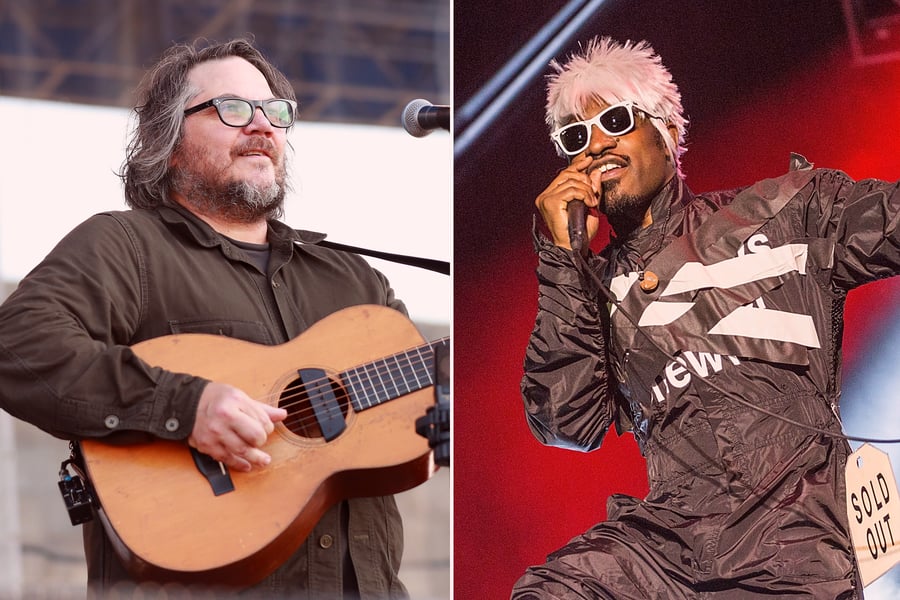

In his new book One Last Song, journalist Mike Ayers asks an array of artists an intriguing, but rarely considered question from the endless realm of pop music hypotheticals: If you could choose the last song you’d hear before you died, what would it be? The book, out October 13th via Abrams Image, uses that question as a launching pad for Ayers’ conversations about life and death with musicians like Wayne Coyne, Killer Mike, Wanda Jackson, Phoebe Bridgers, Matt Berninger, Stephen Malkmus and Angel Olsen. In the excerpt below, Outkast’s André 3000 and Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy share their respective selections, Prince’s “Sometimes it Snows in April” and the Byrds’ “Turn! Turn! Turn!”

In his part, André 3000 weaves together stories about growing older, the impossibly cool older cousin who introduced him to Prince and a near-death experience of his own. He also touches on the recent deaths of his parents and stepdad, tying the jarring suddenness of those losses to Princes lyrics: “Just out of the blue, when I least expected it. Even the lyrics ‘Sometimes it snows in April’ is kind of like . . . it’s not the time it’s supposed to snow. So it means something really serious happened when it wasn’t expected. The mood of the song always clicked in that sort of way.”

Tweedy, meanwhile, recalls how his father latched on to his life-long favorite track, Earl Bostic’s “Night Train” during his final days, and how that nudged Tweedy towards choosing a song that had a similar “full-circle connection.” For him, that was the Byrds, “Turn! Turn! Turn!” which he calls, “the first truly transformative pieces of music I encountered that changed my life in a way. It seems like a sweet thought to have one last listen.”

André 3000 on Prince’s “Sometimes It Snows in April”

I’m a pessimist; I always think of the worst. I’m always thinking of death in some way. In recent years, my parents and my stepdad passed away, so it’s been a little bit of funeral fatigue. This is reality now. The older we get, the more funerals we’re going to. I’m forty-five right now as I’m giving this answer, and I have had to start thinking of things I never had to think about before. I never planned on being an adult. Sometimes, I’m looking around and I’m like, “Damn, I have to be an adult. Fuck!”

When I was younger, I heard “Sometimes It Snows in April” by Prince. That was always a song that summed up what it is. Usually, when someone dies, unless they die of old age or sickness—it happens in a strange way. Both of my parents are gone and they both died early. Just out of the blue, when I least expected it. Even the lyrics “Sometimes it snows in April” is kind of like . . . it’s not the time it’s supposed to snow. So it means something really serious happened when it wasn’t expected. The mood of the song always clicked in that sort of way. I never knew what Prince was talking about, but it sounded like he was talking about a life.

I got into Prince in my early teens. My older cousin, I looked up to him and he had all the girls, all the cool clothes. His girlfriends would come over and they’d hang out. And I got into Prince because he was into Prince. And I’m listening to it—and I’m like, What the hell? You know Prince: he expands and goes into any kinda music. And my cousin, he was the coolest dude I knew at the time, so this Prince dude, he gotta be cool. I didn’t really connect connect to it until I got a little older, like in my late teens, when I started to understand the lyrics a little bit more. To be more concerned with the lyrics. Ever since then, Prince is like an oasis for me. He showed a whole generation you can make any type of music you want. And that’s what it’s about. Prince represented that to me more than anything. It’s all music. Just do it.

When I was younger, me and my friend were in a car accident. We were riding with my friend’s mom, but we were so young, we didn’t know what happened until we woke up in the hospital. I didn’t know. I was a kid. Fortunately, we were on this street in Atlanta and it was a non-busy street. And fortunately this guy who had money passed by—and he had one of the first working cell phones. It was like a suitcase. And he was able to call an ambulance. If we didn’t have that cell phone, we would have been out there for a minute—and might have died. Who knows. I don’t know if that’s a near-death experience. But I was definitely lucky.

Jeff Tweedy on The Byrds’ “Turn! Turn! Turn!” by The Byrds

My father passed away a couple of summers ago. We were all there with him, and one of the things we did a lot, as he was becoming less and less responsive, is we played music. So thinking about this made me think about that quite a bit.

One of the things we did play a lot of was “Night Train” by Earl Bostic. It’s not a song that you would associate with morbidity. And that song worked its magic many times as he was getting sicker, almost to the point that he wanted to get up and dance. It was his go-to whenever he would talk about what his favorite song was. It had some sort of happy memory for him from when he was a young person.

That made me think that it’s kinda nice to have some sort of full-circle connection to a song. And I think one of the first songs that I ever responded to that would feel sort of comforting in this scenario is “Turn! Turn! Turn!” by the Byrds. That’s my choice. There’s something pretty magical about this recording, not to mention that the lyrics are pretty appropriate and I think that’s kind of what the song is about: there’s a time for life and death. This is one of the first truly transformative pieces of music I encountered that changed my life in a way. It seems like a sweet thought to have one last listen.

I was born in ’67, and I bet I was listening to that song by the time I was four or five. And I never really got sick of it. It was a remnant of my sister’s and my aunt’s teen years, because they’re both about fifteen years older than I am. I just inherited their records when I was really, really young.

The structure of the song is pretty unique. It keeps folding in on itself somehow—and doesn’t really have a verse/chorus structure. There’s a forward momentum to the guitar part—and it’s a unique sound that wasn’t common to my ears at the time. For a lot of people, the Byrds’ big calling card was the twelve-string guitar. It was kind of the Beatles’ sound, but never really highlighted on Beatles recordings. It seems to be on those Byrds records. The whole song is pretty much sung in harmony, which is unusual. There’s not really a singer on this song. There’s a vocal that’s a blend, for the most part, and that’s kind of beautiful; it stops becoming a person and becomes a thing, singing these fairly emotional lyrics. But there’s a detach-ment from them; I think it’s one of the ways it succeeds in becoming more like scripture. If Pete Seeger’s version is a guy reading the Bible, their version is more like a choir of angels explaining life and death or something.

The Byrds are pretty foundational, for sure, even for Uncle Tupelo. Without Sweetheart of the Rodeo and some of the transitions that they went through, we might not have found enough country to embrace, you know? To pursue it a little deeper. So that definitely led us down that path to Gram Parsons. Even like Merle Haggard and Merle Travis, and who they were covering. It’s all a part of the stew, that time. But even beyond that—the early Byrds records basically taught me how to sing harmony and that’s essentially what I did in Uncle Tupelo. So, I don’t know how much you can value that as being a huge part of who I am or my musical career—but it’s certainly where I learned it, singing along in the car with tapes of Byrds records. It’s how I earned my keep.

When my father passed away, his girlfriend was playing a lot of Wilco, too. It was almost too much to contemplate at the time. It was almost too profound. I’d probably still cry about it if I thought about it too long. Everybody had made that decision before I had even gotten there. So it wasn’t for me. It wasn’t to make me feel good. But it was extremely touching. They were listening to the box set of outtakes and B sides. Some of those are things I hardly listen to, if ever. Apparently, my dad listened to them a lot. Which makes sense! As a contrarian, he would have thought most of those things should have been on the records and I had missed an opportunity with them.

My sons, Spencer and Sammy, and I did manage to play some songs for him when he was in the hospital and hospice, and at home, when we got to come back. You know, at the time, as sad as everything was, it did contribute to the overall feeling that what we were all experiencing was beautiful and natural and not entirely sad. Just a fact of life. Some relief, in him not being in pain or suffering anymore—but the idea that you can have a good death is not really something you think very often. To witness it, honestly, my predominant emotions were relief and gratitude; not loss and grief, oddly enough. I certainly felt loss and grief, but my predominant feeling was “God, that was a good way to go.”

Everybody spends a lot of time being fearful when it comes to death. And death is like most anything you’re fearful of because it’s the unknown that you’re trying to cope with. And it’s the one thing aside from being born that we all have in common. Nobody who’s been on the planet has not had that experience. I try to remind myself of that all the time.

Death is a pretty common theme in my lyrics. I think all writers have obsessions and I think a lot of writers have that very same obsession. There’s a lot of good reasons for that. It constantly feels like it’s something that you have to take the pulse of: How well am I doing today in coping with my mortality? It’s a constant scab we’re picking at. I personally think that it’s important to do that. I would argue that, at the risk of it being a disabling obsession, I have continued to pursue those thoughts without moderating very much—I don’t think it’s a debilitating obsession. It’s a way for me to remain clear, you know? I think a lot of people are motivated by their fear of death without being very conscious of it and it allows them to do some pretty negative things. But if you have it in the corner of your eye a lot of the time, for one thing, it allows you to be more appreciative on a day-to-day basis, more appreciative of your life. Being less compelled by your fear to shut down or tune out your fellow man.

Excerpt from the new book ONE LAST SONG: Conversations on Life, Death, and Music by Mike Ayers. Courtesy of Abrams Image, an imprint of Abrams Books. Copyright 2020.

From Rolling Stone US