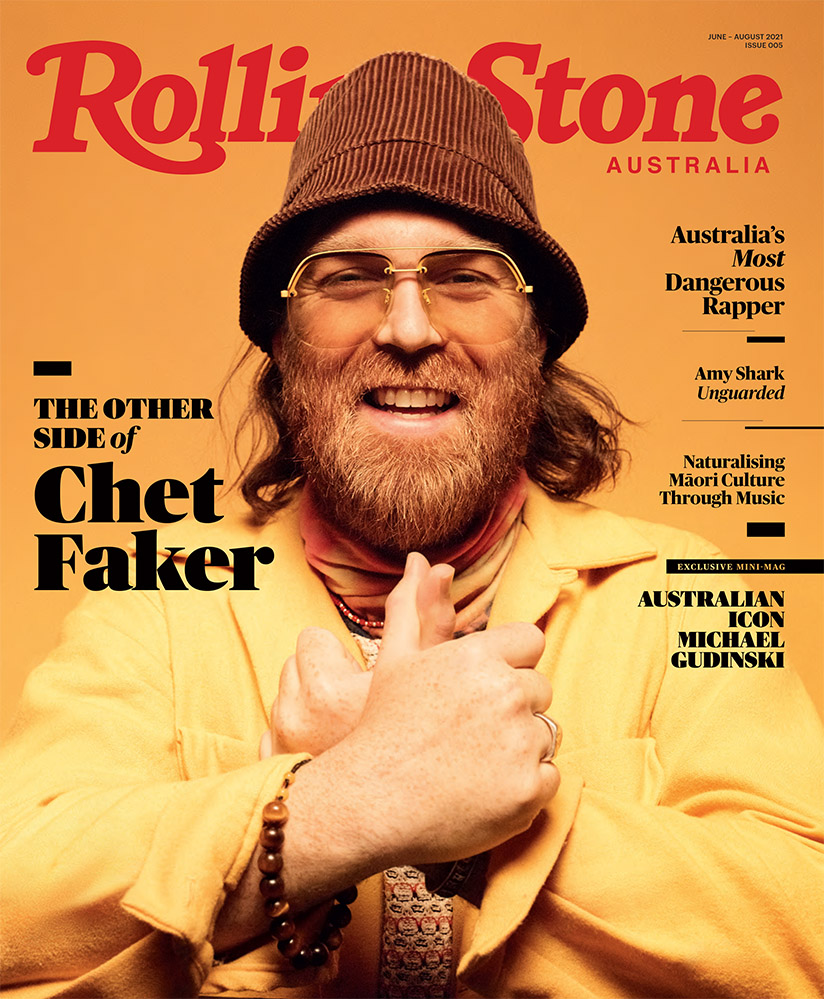

Willy Lukaitis for Rolling Stone Australia

As Nick Murphy returns to the spotlight with his first Chet Faker album in seven years, the globally-recognised artist speaks to Rolling Stone about what’s really in a name.

No one ever killed Chet Faker, but for years now, the Australian music industry treated this world-beating, chart-topping artist like he was a thing of the past; a brief moment of light in the annals of music history. However, the truth is Chet Faker never went anywhere, and the man behind the project – Nick Murphy – knew it would always be a part of his life.

So why then, when it was revealed after four years that Murphy would be bringing the project back, did it seem as though we were witnessing the grand return of one of the country’s favourite artists?

Chet Faker, photographed for the cover of Rolling Stone Australia in New York on April 10th 2021, by Willy Lukaitis. Styling: Ellen Purtill. Studio: Vivid Kid Studio)

For most of the last decade, the Australian music scene found themselves becoming familiarised with Nick Murphy and his Chet Faker project, though his musical origins stretch back to the early years of this century. Having taken lessons for piano and saxophone as a young child in Melbourne, he took up the drums while attending Toorak’s St Kevin’s College. Despite this, he never called himself a musician, rather, he identified more as a gamer. However, it was creativity that helped him get through what he explains was likely an episode of undiagnosed depression.

“I didn’t really know what was going on,” he recalls from his New York City apartment, the evening sun blazing in and reflecting off the litany of instruments strewn around. “But all I knew was that I was sad and I had all these feelings – as most teenagers do. And I found in music a kind of release from that feeling.

“I found that to focus on music and to kind of climb into these songs that I was writing seemed to take this pressure off of my chest and out of my being and put it into the recording. I became kind of obsessed, I was obsessed with it. The beats. I was playing guitar, I was learning piano, and I was singing. So, I really just went in head-first.”

“All I knew was that I was sad and I had all these feelings – as most teenagers do. And I found in music a kind of release from that feeling.”

Kick-starting his career by utilising Sony’s ACID Pro software, Murphy remembers requesting a new version of the program for his 16th birthday, only for his mother to give him Ableton Live instead. A blessing in disguise, Ableton Live would later supersede Sony as industry standard software, allowing Murphy to face his dreams head-on.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“I knew I wanted to make music, because I knew that I was born to make music,” he explains. “I hear songs in my head. I wake up from dreams [and] I can hear all the parts. Music is just like, it’s my first language.”

Bolstering his skillset by utilising a piano at his grandmother’s house, Murphy soon began to share the music he had created. Early projects included the alt-rock band Sunday Kicks, and the electronic duo The Knicks, but it was the folk-inspired work of Atlas Murphy that set him on the path to where he is today.

“I knew I wanted to make music, because I knew that I was born to make music.”

Influenced by the likes of Jeff Buckley and Bob Dylan, the single-take approach to Atlas Murphy revolved around the idea of “trying to singularise and capture human performance,” with a much more organic attitude towards creation. Not content with focusing on just one side of the musical equation, Murphy soon birthed Chet Faker as a way to provide an alternative, with his nascent product envisioned as an opportunity to focus solely on instrumental music, playing close mind to production and sonic worlds.

It was this project that stuck, however, with early tracks like “Nevermind Sleep”, “House Atriedes”, and “Injections” being overlooked in favour of a cover of Blackstreet’s “No Diggity”. The latter promptly went viral after being uploaded to SoundCloud in April of 2011, giving him massive attention both here and abroad, almost overnight.

“‘No Diggity’ wasn’t a cover until the very end,” he recalls. “It was like, ‘I like this so much, I’m going to put vocals on it,’ and I happened to pick that song out of a hat to cover. It could have very easily been an original thing, but I wonder if it would have gone viral.”

Even in 2021, his cover of “No Diggity” boasts close to 140 million streams on Spotify, an example of the overwhelming level of fame he stood on the precipice of.

“No one’s ever had a conversation with anyone about what you’re supposed to do if things go well.”

“No one’s ever had a conversation with anyone about what you’re supposed to do if things go well,” he notes, recalling the sudden attention he found heaped upon himself. “All I knew was that apparently this is what I wanted. I thought that that’s what I wanted and I didn’t want to make a mistake.”

Almost instantly, Murphy found Chet Faker in high demand, with his debut EP Thinking In Textures arriving in early 2012. Now regarding the EP’s composition as being “naïve and childlike” when compared to his later works, it served as another step in a rapid rise to the top. Before he knew it, the EP’s success took off and Murphy found himself going from creating a body of work in his mum’s garage between work and uni, to touring the world.

“I must have been the only artist in the world to be playing those festivals and those spots with just a five track EP out,” he recalls. “It was really crazy.”

In between global tour dates, Murphy managed to find time to work on a follow-up. Working from a studio for the first time, he focused his efforts on what would become his debut album, with an intent on creating something more considered, with more depth. Something that would help erase his status as “the ‘No Diggity’ guy”.

“You almost always have a thing that everyone references, no one wants you to do anything else until you’ve made something that’s better than that,” he laments.

Dubbed Built On Glass, the 2014 album was a massive success. It topped the charts in Australia, was nominated for multiple ARIA Awards (winning Best Male Artist, Best Independent Release, Best Cover Art, and both Producer and Engineer of the Year), it was shortlisted for the Australian Music Prize, and lead single “Talk Is Cheap” topped triple j’s annual Hottest 100. But the stress of such a rapid ascent wasn’t too far behind for the admittedly ill-prepared musician.

“I don’t know if I was fully equipped to deal with it,” he explains. “I try not to be too negative about it, because it’s my journey and I’m so grateful to have these opportunities and things. But I definitely look back and wish I could kind of go back, talk to myself at that time, and kind of break it down for me.

“I just didn’t have any guidance. I didn’t have anyone around me that was looking out for me. I had some people that I thought were, but in retrospect I just don’t think that anyone really fully understood what was going on and what it felt like.”

“In retrospect I just don’t think that anyone really fully understood what was going on.”

Murphy adopted an almost nomadic lifestyle as a result of his growing fame, with 2014 seeing him perform around 135 shows. Moving to New York City to facilitate quicker travel to these international tour dates, he was left feeling isolated as he attempted to make sense of this sudden spotlight.

“I developed variants of agoraphobia in those years,” he admits. “Just from really feeling like an animal in a cage, of not really feeling like I had a place to be safe and really not feeling like anyone around me was particularly trying to make sure that I had a healthy balance of being in the limelight and then having a life.”

It was around this time that Murphy realised it was time to follow his gut and take the next step in his creative journey. While it was in late 2016 that he would publicly move on from Chet Faker and return to releasing music under his birth name, the man behind the moniker had felt it was coming for some time.

“I did say [the name change] is an evolution, which is true. But look, I’m going to be totally honest, I was just following this instinct,” he notes. “I think that to truly be a creative, you are following something else. You’re not leading. You’re following this inexplicable whisper, this shadow of yourself.

“I’d reached this point, this apex of success that had gotten so big. I was recording with Rick Rubin, hanging out with Neil Young in the backyard [of Rubin’s Shangri-La studio], Ellen [DeGeneres] asked me to come and play on her show, all this stuff and I really had to take a look at myself and ask myself, ‘What do you want?’

“On one hand I was afraid of losing what I’d got, this success. And so I think subconsciously I wanted to remove it myself. I didn’t want this thing to bear over me and possibly affect my decisions.”

Having toyed with the idea of releasing music under his own name for some time, Murphy notes that it was Rubin who inspired him to follow this path and to make the music he felt born to make. Despite fearing a lack of commercial success or potential confusion, Murphy realised it was time to embrace this other side of his musical psyche and make it clear to everyone that Chet Faker, as the public knew him, was in fact just a project, and something that stood in the way of people getting to know the real him.

“Now there’s success and shit and I’m just kind of like, ‘Well, what about the rest of it?’,” he reflects. “‘I’m only 24, 25, who am I?’ Everyone’s telling me they love me or they know who I am and I’m like, ‘Well wait, that’s a project’.”

In late 2016 though, Murphy made the decision clear, taking to social media to announce the news, alerting his fans to an “evolution”, and explaining that while “Chet Faker will always be a part of the music,” he would be utilising his birth name from now on. While this post is considered a pivotal moment in the story of his career, Murphy explains he never exactly wanted to spell out his intentions to the world.

“I just wanted to just go and do the music, but everyone around me was kind of like, ‘You’ve got to tell them what’s going on’.”

“And I’m like, ‘Well, you know, I just think talking about it is going to confuse people more’. In my experience, you can talk about something to a certain extent, but if these things were easily explained then why on earth would anyone be using the abstract language of music or art to explain it? It’s bigger than language.”

To his surprise though, the reaction was swift and divided, with many fans taking it to believe Murphy had completely turned his back on the music they loved, while the other half of his fanbase expressed their support for him following his artistic vision.

The fruits of this new labour soon arrived in early 2017, with Murphy sharing his Missing Link EP. While the Run Fast Sleep Naked album was released two years later, 2020 brought with it much more material, including a run of cassette releases, and the Music for Silence album, released in conjunction with the Calm app. Despite being more commercially prolific as Nick Murphy than Chet Faker, he explains that the former project wasn’t far from the minds of fans.

“Still now, people will tell me to bring back Chet. As if it’s a person; as if I’m not him.”

“It was pretty funny to watch people flip out,” he recalls. “Still now, people will tell me to bring back Chet. As if it’s a person; as if I’m not him.

“It’s really weird, as if I have a twin brother that I beat across the head with a spanner and locked him in the basement and everyone’s like, ‘Let him out,’ and I’m like, ‘No’.”

Of course, Murphy wasn’t the first artist to change their name, with the likes of Prince changing his name to a symbol, and Puff Daddy changing monikers like he changes clothes.

“I think the point is more about the fact that you did it,” Murphy muses. “That you weren’t afraid to strip the very tag that people were buying into.”

“It’s really weird, as if I have a twin brother that I beat across the head with a spanner and locked him in the basement and everyone’s like, ‘Let him out,’ and I’m like, ‘No’.”

While the public sector seemed almost universally confused by the decision, Murphy’s inner circle seemed to understand it much better – an added benefit of being close to the artist and understanding his thought process.

“It didn’t really feel like he was retiring the name,” adds close friend and Australian-born chef, Magnus Reid. “He was like, ‘I’m just going to do Nick Murphy music for a while’.

“It felt more like he’s [thought], ‘Chet Faker’s cool and it was something I’ve done and it was something I can do. But if I’m going to look and see how far I can push this, and what I can achieve with it, then I’m going to be Nick Murphy, I’m going to be myself’.”

“It didn’t really feel like he was retiring the name. He was like, ‘I’m just going to do Nick Murphy music for a while’.”

The modern revival of Chet Faker was as unexpected to Nick Murphy as it was to his fanbase. 2018 and 2019 were, by his own admission, a difficult two years. An existential crisis brought on by the reading of Gaston Bachalard’s The Poetics of Space and having turned 30, saw Murphy embark on some travel, while 2019 brought with it stress within his inner circle. Murphy was forced to let many of the people he worked with go, including a change in management and the near-cancellation of a European tour.

“It was just super intense. I lost all this weight and I was just running on pure adrenaline,” he recalls. “It was crazy. Like, 2020 was almost chill compared to my 2019.”

(Photo: Nick Murphy)

It was in this time that Murphy met now-manager Alex Frankel, a founding member of Brooklyn duo Holy Ghost!. While Frankel was previously aware of the Chet Faker name, the pair had not met until he was recruited to help recalibrate Murphy’s live show. Almost instantly, Frankel recognised the sort of talent that the artist holds.

“One of the first times we met, we were going to set up some gear at the rehearsal space, and Nick was just kind of fucking around on piano,” he recalls. “Nick did that thing where he sat down at the piano and played for a second and sang for a second and, every head in the room turned and goes, ‘Oh, holy shit!’

“That’s a timeless kind of classic talent that’s increasingly rare in the music industry. I noted right away just kind of how real his talent was – both as a piano player and as a singer.”

Recruited as Murphy’s manager (though he describes himself as more of a business or creative partner), Frankel quickly helped Murphy stabilise, finding him both a new apartment in Manhattan’s Chinatown neighbourhood, and a new studio in nearby SoHo.

“Little did we know a month later a pandemic would hit and that studio would be invaluable. Nick was in there every day,” Frankel remembers. “We were slowing things down a little bit but they were starting to [announce] gigs. There were supposed to be shows – festivals starting in May and then Italy in June.”

(Photo: Jelani Roberts)

However, the silver lining to a year on hold meant Murphy was able to go back to his roots somewhat and write and record music like he hadn’t been able to for many years.

“When your career really gets going, it’s really rare that you get to go back to that high school place [feeling of] really starting out. Where it’s just you alone in a room with your gear and your computer; it’s not scheduled, it’s not with a producer, and you’re not on the clock.”

“During the quarantine, I was still able to go to the studio for a lot of it,” Murphy adds. “And then [I would] bring stuff home when I couldn’t and just make music all the time. it was kind of a real saviour for me. It was kind of like my coping mechanism.”

As it turned out, this period proved more fruitful than even Murphy could have imagined. With time on his hands, these sessions soon gave way to a problem that many artists wish they could have: he’d accidentally made a record.

“It wrote itself,” Murphy explains. “I mean, I’ve had songs write themselves, but I don’t even remember working to finish this album. It was the most effortless thing, album or piece of music I’ve ever done.

“It just kind of showed up and I was sort of looking at it and I was like, ‘Damn, this is a Chet Faker record’.”

“It just kind of showed up and I was sort of looking at it and I was like, ‘Damn, this is a Chet Faker record’.”

Frankel, who had spent much of his first few months working with Murphy and ensuring there was a clear split between Chet Faker and Nick Murphy on digital service providers such as Spotify, confirms this, noting that Murphy started to realise he’d made music he hadn’t expected to.

“I was under the impression that Chet Faker was something of the past or that might come back one day, but that was not something we discussed,” he recalls. “And then as Nick was sending me the demos and, silently in the back of my head, I was like, ‘This sounds like a Chet Faker record’.”

Indeed, the pair had hit upon a common realisation. However, Murphy’s own apprehension at the record being perceived as him wanting to bring the former project back, led to a brief period of uncertainty and soul-searching on both sides.

“I said, ‘Just take two days and we’ll both meditate on it and we’ll speak Monday’,” Frankel recalls. “On Monday he called me and he’s like, ‘So what do you think?’ And I was like, ‘What do you think?’ And I think we said it at the same time, we both were like, ‘It’s a Chet Faker record’.”

“I remember at the start of lockdown he [spent] a month in the studios,” adds Magnus Reid, reflecting on his communication with Murphy across 2020. “He’s like, ‘Man, I keep writing all these Chet Faker-style songs. I guess I should just put ‘em out, huh?’

“I kind of saw that was the kind of thought process. It’s like, ‘Well, they’re coming out at me so people are going to get them’.”

“At some point it will make complete sense. Like when Radiohead put out Kid A, it didn’t make any fucking sense at all, but it does now.”

While the final product, Hotel Surrender, was an unexpected appearance in his life, so too were its effects. Tragically, the record’s completion coincided with the news of his father’s passing, and with borders closed due to COVID-19, Murphy was unable to attend the funeral. However, the record itself served as a way to help him cope with such tragedy, providing a sense of perspective on life itself, and giving his music an opportunity to serve as a beacon of hope in what had been an otherwise terrible year.

“The record, it’s very positive,” Murphy notes. “I mean the opening monologue is kind of this cowboy Western […] fictional story of a reality.”

“Just because I feel low right now / It doesn’t mean all that I’ve got has run out,” Murphy sings, as he touches upon issues of depression, uncertainty, and ultimately resilience, later explaining that the track’s message somewhat paralleled the title of George Harrison’s 1970 solo album, All Things Must Pass.

“That was kind of it. It’s how I’ve always engaged with my own experiences of mental health or just life in general,” he explains, noting that it’s important to acknowledge the low points, but to realise there is a light at the end of the tunnel.

“I think it was just really helpful for me to have something positive to work on. It’s a really positive record,” he adds. “Everything seemed so dark [in 2020] and I kind of had this bright coloured project, an album that I could deliver. It felt kind of bigger than me.”

Ultimately, both the record’s creation and its arrival were the product of perfect timing, with Murphy not only explaining that it seeks to help people in much the same way it helped him, but had he attempted to make the record following his father’s death, it likely wouldn’t have become what it is today.

“What I was getting from making that music and this record, and working on it, it almost felt not right not sharing it,” he explains.

“I remember I’d finished the vocals or the singing before dad had passed,” he recalls. “And I remember thinking there’s no way I would have been able to do this now.

“I was really glad that I’d had it done in time, because […] it was able to help me feel positive and better about it all. And I think that’s what led me to realise like, ‘Fuck, this can really help people’.”

“I remember I’d finished the vocals or the singing before dad had passed. And I remember thinking there’s no way I would have been able to do this now.”

Of course, with a new album arriving from his Chet Faker project, and with fans now getting used to Murphy’s much more public musical double life, the next battle he faces is explaining just how the two facets of his musical being coexist. Though connected by the artist behind them both, each piece of music created by Murphy comes from a far more considered place, with the two projects coexisting as different sides to the same coin.

“In my head, Chet Faker is sky and Nick Murphy is earth,” he explains, pointing to the fact that while records such as Built On Glass and Hotel Surrender feature a sound much more “immediate” and “intentional”, much under the Nick Murphy name requires a deeper listening in order to be fully appreciated.

“I love music like that,” he admits. “That requires a kind of engagement from the listener. It requires you to put some of you into the listening as well. And I think I recognised that was never going to fly with the Chet stuff, that wasn’t what I’d built.

“I’d built this house of satisfaction, so to speak. And then I wanted to go off into the corners you know, so that’s what the Nick Murphy stuff is for me. It’s a place where I can go off the beaten path and I can be less direct with what I’m saying.”

In much simpler terms, he notes that Chet Faker exists to lift its listener to a higher plane, providing a satisfying, considered sound, while Nick Murphy serves as something of a reality check, with gritty, unadulterated truth.

“I’m hesitant to say musically what the differences are because I’ve got a whole lifetime ahead of me for that to answer itself.”

“I’m hesitant to say musically what the differences are because I’ve got a whole lifetime ahead of me for that to answer itself.”

As Hotel Surrender arrives into the world, it’s clearer than ever that the future truly belongs to Nick Murphy – whichever musical moniker he chooses to go by. He admits he’s already working on another album, the question remains as to what form this will take. Will it be the considered sonic compositions of Chet Faker, or will it be the unfiltered reality of what his birth name lends itself to?

“He’s got like five, six, seven albums recorded worth of music. At least,” notes Reid. “And then he’s got hundreds of thousands of half recorded stuff and I think, eventually all those ideas that are in that pile of music are going to get out there. But you know, he’s got to put them out piece by piece and this is the way he’s doing it.”

Though many fans (and even some of those within the industry) would likely prefer a much more clear-cut idea of who Nick Murphy is, who Chet Faker is, and how the two coexist, the fact remains it’s the beauty of this uncertainty and unpredictability that makes Murphy who he is.

“This is a career artist who is hopefully going to do many different things, have many different projects and they may not all fit in the same cookie cutter,” Frankel plainly states. “And anyone who isn’t excited by that is probably in the wrong business.”

Chet Faker’s Hotel Surrender is out now via Detail Records/BMG.