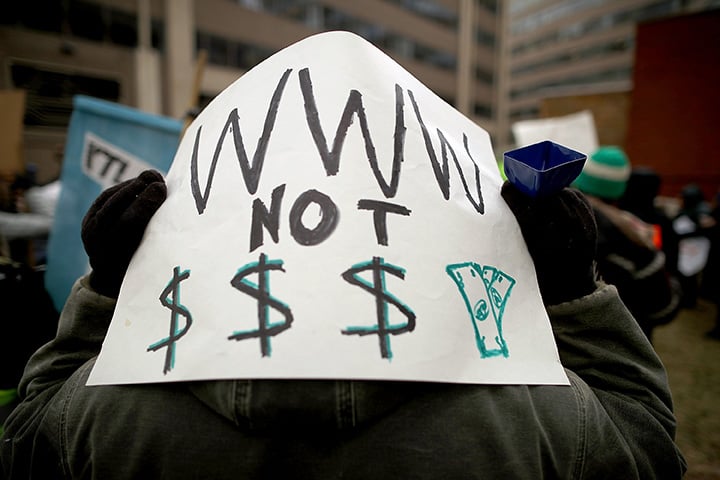

In a decision dreaded by advocates of a free and open Internet, the U.S.’ Federal Communications Commission voted on Thursday to overturn regulations mandating net neutrality. The move represented a major victory for Ajit Pai, the former Jeff Sessions staffer and Verizon lawyer who was appointed chairman of the FCC by President Donald Trump, and has long crusaded against what he calls “heavy-handed” regulation of the telecommunications industry.

The decision is likely to have major ramifications for consumers, online businesses and Internet service providers (ISPs). The existing regulations, put into place by Pai’s predecessor Tom Wheeler in 2015, codified longstanding Internet practice by explicitly requiring ISPs to treat all Internet traffic equally. In contrast to a cable provider, which can decide exactly what networks or services customers get for their monthly fee, ISPs are forbidden from discriminating among their customers. When you pay your fee to get online, you get everything. But under the new regime, a handful of the most powerful telecommunication companies in the U.S. – Comcast, Verizon, AT&T – will have unlimited freedom to slice and dice the Internet ecology as they please.

What does this mean for you, me and your favorite app? The most likely outcome, say net neutrality advocates, is that prices will go up, variety and diversity will go down and the largest, best-capitalized Internet companies will gain a significant advantage over upstart competitors. It’s a punishing blow to believers in the founding dream of the Internet as a great equalizer, a network that grants everyone free rein to do anything.

“There are going to be fast lanes and slow lanes,” says Gigi Sohn, a longtime public-interest advocate and telecom analyst who served as counsel to Wheeler during the 2015 net-neutrality fight, during which a broad coalition of Internet companies and online advocacy groups convinced both the White House and Wheeler that net neutrality was crucial, not just to a free Internet, but also to a thriving Internet economy. “As a consumer, that means some of your favorite websites are going to load more slowly, and it also may mean some of your favorite content goes away because the provider just can’t pay the fee.”

“You are no longer going to be the one in control,” says Sohn. “Comcast, AT&T and Verizon will pick and choose the winners and losers, instead of you choosing winners and losers.”

Let’s say you are a regular user of Amazon, eBay and Etsy. Right now, you’ve got all those apps on your phone or laptop, and they all work pretty well. Pages load fast, orders go through right away. But you get your service through Verizon, and now, with its net neutrality shackles broken, Verizon is free to say to all three online retailers: Hey, if you want to be in the fast lane of the Internet, you will have to pay for our premium package. Amazon and eBay can afford to do this, but Etsy can’t. All of a sudden, Etsy is in the slow lane, and now when you try to search for a “FCK THE FCC: SAVE NET NEUTRALITY” T-shirt to wear to your next protest, the page takes forever to load.

It was exactly this scenario that inspired Chad Dickerson, the former CEO of Etsy, to help lead the 2015 fight to enshrine net neutrality as government policy. He says studies have shown that fractions of a second can make all the difference.

“Speed has an enormous influence on transaction volume,” says Dickerson. If a website is slow, users will abandon it. Allowing those with the wherewithal to pay for faster access to the Internet gives big, incumbent companies a huge advantage over smaller startups. “Net neutrality allowed something like Etsy to hang out a shingle on the web and give it a try,” says Dickerson.

It gets worse. Because under the new rules (or really, lack of any rules whatsoever), ISPs won’t just be free to charge more for better tiers of access, they will also be free to block access to whatever part of the Internet they feel serves their financial interests. AT&T could cut a deal making Microsoft Bing its default search engine, and block Google entirely. Comcast might decide that it makes no sense to allow Netflix to compete with its own streaming services, and strangle off access to the site. Verizon could decide that Fox News’ reporting is more in line with its corporate interests than CNN or The New York Times.

In a truly competitive marketplace, corporate moves such as these would be suicidal.But the brutal truth is that most consumers have few alternatives. According to the FCC, almost 50 million US homes (out of 118 million total) have access to only one, (or none at all), high speed broadband provider. Consumer choice is an illusion.

Sohn calls Pai’s push to abolish net neutrality a basic “abdication” of the FCC’s responsibility to regulate the telecommunications industry, a startling declaration that the “FCC should have absolutely no role in overseeing access to the most important network in our lifetime.” And she points out that once the issues at stake are explained to the average citizen, abolishing net neutrality turns out to be extraordinarily unpopular. Recent polling shows that more than 80 percent of Americans support net neutrality, a rare case of bipartisan unity. Sohn says that she’s heard from legislative staffers that they are getting more calls on net neutrality than tax reform, a fact that might explain why a handful of Republican legislators started calling for a postponement of the FCC vote earlier this week.

It’s not hard to understand why. “When we were fighting our battle, we really felt like we were fighting for the people because they wanted free and open access,” says Dickerson. “How many average citizens think their ISP have their interests at heart?”

So for now, it’s the end of the Internet as we have known it. But the battle might not be over for good. A legal effort to overturn the FCC’s decision is expected to begin immediately. Congress has the power to pass legislation restoring net neutrality. A generation of millenials, suggests Sohn, who have grown up taking the advantages of a free and unrestricted Internet utterly for granted, “care deeply about this.” There will be no better way to demonstrate that care than by turning out in the U.S. 2018 midterm elections and voting for politicians who endorse net neutrality.