Mario Alzate

Juanes has a spot among the legends. He walks among the greatest to give us one of the best tribute records in the history of Latin music.

It is a typical afternoon in Florida. As usual, the weather is warm. Juanes has a glass of red wine in his hand and shows off a long blond hair that reaches his shoulders. He’s sitting in his home studio, wearing dark glasses and a black shirt. For more than a year, he has kept a mandatory lockdown that has helped him find himself, write and produce, while still questioning his career as if he was in his twenties. Now, at 48, -which seems less- he is quite sure of the purpose of its art, its sound, and its strengths. A few years ago, the industry wanted to pull him away from his instrument and now he presents his new album “Origen.” An analogous and honest album, loaded with neat guitar solos that let him express who he really is. “This is all about what I wanna do, and to do it with love from my art, my origin.”

The last time I interviewed Juanes was in 2017, we talked for days in Miami. Besides talking about “Mis planes son amarte,” we went deep in Colombia’s political situation, his stance on reggaeton and, mainly, his exploration of the urban sound. And as if this were a linear narrative, this interview follows that conversation; how the ending of a cycle is the beginning of another, and how after some years of exploration, he gave it all to a sound that has been the trend during the last decade, at a personal expense.

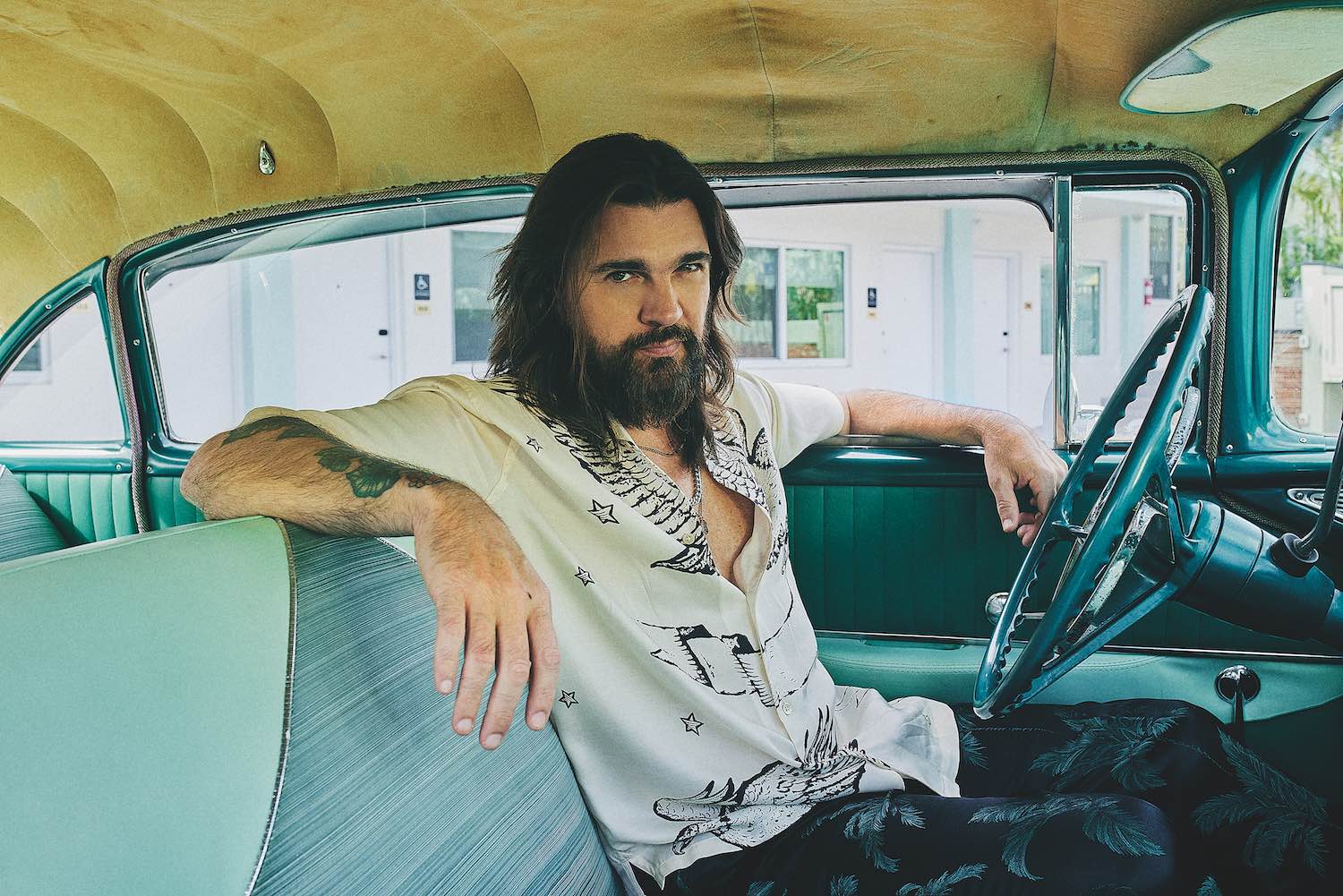

Photograph by Mario Alzate

Perhaps circumstances haven’t changed since then. Reggaeton continues to lead the charts, the industry continues to reward records that have great visibility due to million-dollar marketing strategies, and social injustice detonated throughout Latin America, which has never ceased to be a concern for him. However, he’s in one of the most important moments of his career: the road to posterity. To be remembered forever, even while still active, for his work, music, and songs.

We held this interview during several sessions after having listened to “Origen.” Usually, Juanes is warm and joyful but that doesn’t mean he lacks depth and seriousness when it comes to important issues. After a 30-year-old career in music, his vision seems to be defined: to do as he will, to rediscover an organic sound that he had on hold, to keep writing and producing better songs, and he even claims to play guitar better than ever. He’s still involved in various projects surrounding music. He enjoys the conversation and there’s no room for an act or a promotion script. His honesty, which might have given him trouble before, now is spreading in his discourse and purpose.

There’s something genuine in the songs Juanes chose for “Origen.” His passion for popular music has been clear since the beginning of his career, and the folk nuance of his guitar has represented his identity and sound. When he was a child, every December he went on holidays with his family to Carolina del Príncipe (the town in which his parents were born). “I love that place. I loved the months we spent there because it’s one of the things I remember the most. It was a beautiful time of my life.”

After moving to Medellín, his father conserved an old house in town. His parent’s room was on the second floor and two more bedrooms -one for his brothers, one for his sisters- were downstairs. It was usual that from seven o’clock at night the bar on the block would start blasting music out loud, so he would always fall asleep with popular music in the background. This was his first encounter with music. “At the time I didn’t know what rock was. I only knew popular music, it was the only thing that could be heard from the bar, and my siblings listened to it at home. I’m very connected to that since I was very young, and I love it.” The guitar riffs inspired in folk and old vallenato music defined his sound. “It was kinda like bar music, I don’t know how to say it but it does have a lot to do with my life. That’s why the album is called ‘Origen.'”

From a very young age, he created bonds with important musicians, the same that he had been listening to for many years (Metallica, Juan Luis Guerra, Fito Páez); artists with whom he shares his love for music and songs. Many of them have been able to put their work and art above fame. For more than 20 years, Juanes has created a career among art, exploration, and technical rigor, which has led him to participate in several of the most important tributes in the last decades – such as Prince’s or The Eagles’. He has done so without being intimidated when performing anthems in the history of music, heightening the name of Colombia, and all the more, showing his worth and interpretive capacity.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“Origen” opens up with “Rebelión,” a song about slavery during the colonial era in Cartagena. Joe Arroyo is an artist with whom Juanes has always had a special bond. In 2002, he included “La noche” in his album “Un día normal,” which he recorded alongside Chelito de Castro, recurrent producer in Joe’s career. In “Rebelión,” he makes a minimalist rock interpretation, replacing horns with guitar riffs with a raw and metric sound.

At the old house in Carolina de Príncipe, listening to all Gardel’s vinyl and songbooks was a family tradition. “We would listen to his songs day and night. This connection that I have with music was like the playlist of that moment.” In “Volver,” he does a carbon copy of the original in terms of melody and instrumentation. His approach is respectful, and without overshadowing the original, glimpses of guitar notes can be heard.

The mutual admiration between Juanes and Juan Luis Guerra has been inevitable. For Juanes, the Dominican has been like an oracle throughout his career. He even produced his live MTVUnplugged album. Juan Luis represents a period in Latinamerican’s life – we lived the 90s among rock, salsa, and merengue. As Juanes rehearsed some Slayer cover with his friends, just like any other kid during that time, he would also dance to 90s merengue in some miniteca [small party usually held by schools] at his school. “I was never a radical metalhead, and I always thought there was no reason to be an extremist. Juan Luis changed dance music forever, and he has been coherent since then, in his music, in his sound. He’s unique.”

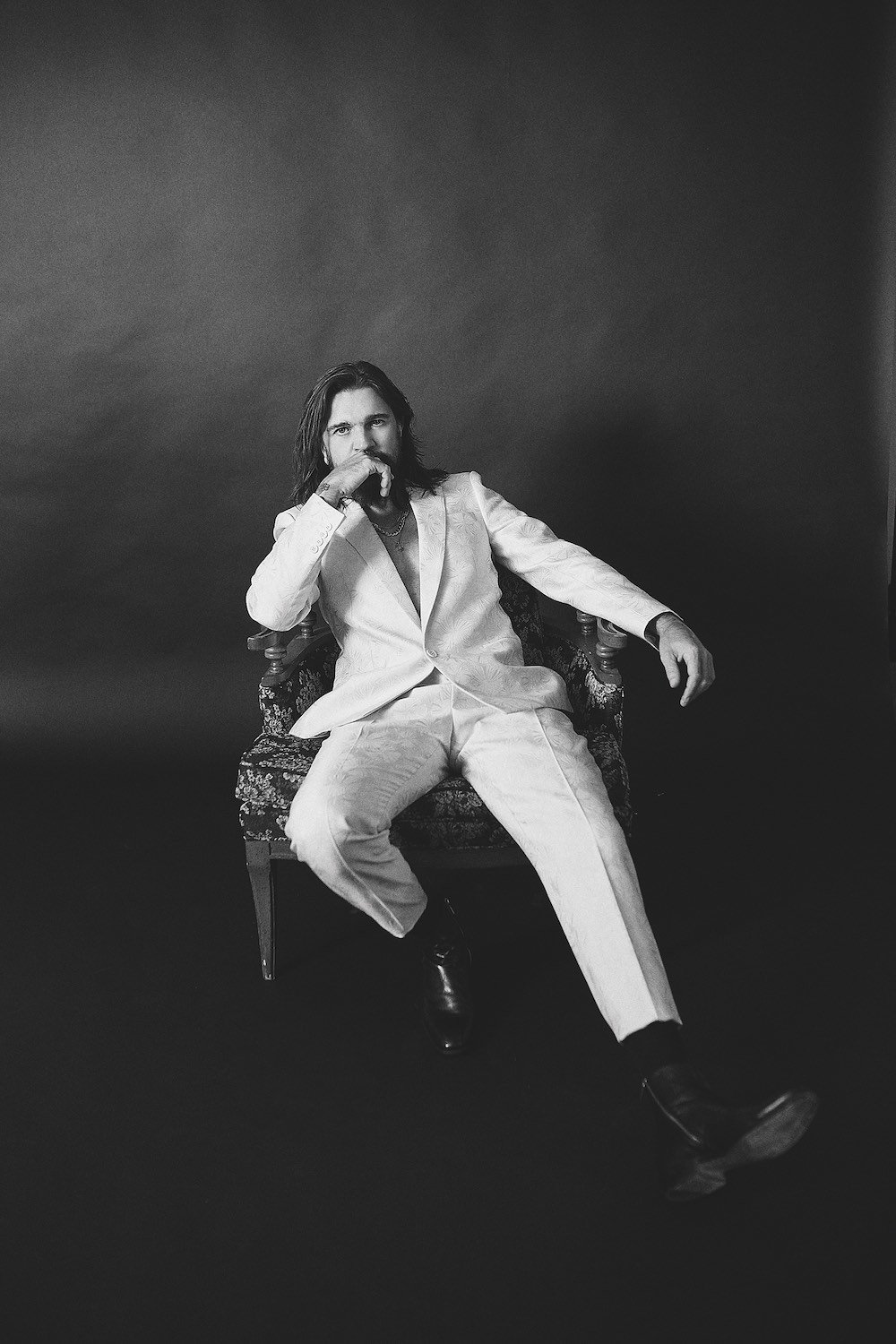

Photograph by Mario Alzate

“La bilirrubina” may be the song that has the most structural changes from its original version in “Origen.” Juanes makes a ska-based cover, with meticulous care on the technical and production details. He also invited musicians from The Roots to play the winds. “We wanted to give it a different vibe, a more vintage one, something different.” It’s hard to say for sure, but this version has the potential to put this song back at the top of the charts. Juanes worked on this Spanish music anthem in such a neat way, that for a moment he manages to make us forget the original.

Juanes and Ziggy Marley have played live “Could You Be Loved” by Bob Marley twice before. A song that represents the time spent at college and in bars in Medellín. “Reggae was what we heard other than Slayer, when we hung out with girls.” With this song, Juanes wanted to do something completely different. “[Bob Marley] created reggae, so I tried to explore other minimal sounds. I was looking for a tribal sound with guitars and percussion. This is proof that I wasn’t trying to beat these songs, they were a fucking hit on their own.”

One of the biggest hits in “Origen” is his cover of Juan Gabriel’s “No tengo dinero.” A punk-grunge approach to one of the first and biggest hits from El Divo de Juárez. The singer shows interpretative mastery, giving the Mexican classic an esthetic and sonic twist. “Man, Juan Gabriel blew my mind. He was brilliant, generous, and fun. They would play him on my school’s radio. Sheer greatness. In this song I just wanted everything to sound great. I can already imagine myself playing it live.” Synths, guitars, and a hi-hat sum up his brilliance and strengths.

On “Dancing in the Dark,” Juanes made a Spanish adaptation of Bruce Springsteen’s classic. It’s a mixture of Brazilian and folk sounds that can seem like a country song in Spanish. “That’s a very tough character. I wasn’t so sure about what the song was about until I translated it. It’s a very, very vulnerable song, which I thought made it even better. I met him at South by Southwest, and I was astounded. I have a collection that my sister and her boyfriend gifted to me. I didn’t even know who he was at the time. Years later, I knew.”

In “Origen”, Juanes delivers a masterpiece with an artistic production based on organic and similar arrangements. Once again, he demonstrates all his potential with an honest and exquisite product that goes beyond the nature of the songs. He demonstrates that the origin of his music comes from the fusion between rhythms and sounds that combined throughout the years, shaping his judgment as a musician and as a producer. Without meaning to, Juanes turns every song into a groundbreaking tribute in the history of Spanish music, while glorifying some of our culture’s greatest legends. Watching him play this album live will be refreshing and necessary in a moment in which the industry seems to be only paying attention to likes and views.

Juanes has a spot among the legends. He walks among the greatest to give us one of the best tribute records in the history of Latin music. He’s an artist who’s no longer afraid. He has explored different rhythms, trends, and sounds without a blink. He’s not bulletproof. Sometimes he has missed, and in many others, he has won. But now, his vulnerability and determination translate into genius and brilliance: the grandeur of Spanish-language music.

When I heard this new record, the first thing I thought was that it’s really risky. To work on this kind of hits, these anthems that are so important in Spanish-language music could end up being a big success or a monumental failure. How did you take on such a big challenge?

I’m not looking for millions of likes. For me, it’s something deeper, it involves wanting to do things that relate to me. I did this when I wanted to do it, and it’s not something that I wanted to do just now, it’s been a while. I really wanted to make a record like this. We even did everything before the pandemic began. The plan was to finish recording it during the first week of March and release it in April, but everything was delayed. And of course, there’s a risk, but this is what I wanna do. I’m not waiting nor wondering if the radio is gonna play these songs. Whoever wants to hear it, will do it. On the other hand, when concerts come back, this album will be a whole experience live. The origin of the songs has to do with the music that I listened to as a kid. Besides, it was also a great opportunity to record and produce songs that don’t have the weight of being my songs. I can interpret them in different ways and pay homage to these incredible people with incredible songs. We wanted to go as far away as possible from the originals and make versions that had something to do with my sound, or at least with how I’m looking at things, how I wanna do them.

Thinking about the audience and your fans, don’t you think there’s a great risk there? Regardless of the quality of the song, people who love these songs can either love or hate your versions.

Yes, 100 %, but that’s unavoidable. How do I control it? I don’t have power over that, I have power over what I do, and how much love I put into it. Only I know how much they mean to me. Nobody can take that and my connection to each one of the songs, away from me.

For how long have you wanted to make a tribute album?

When I came to the United States, I saw that artists pay homages during the middle of the show. And I have always liked that, it is a part of me. In several of my concerts or during backstage, anywhere in the world, Juan Pablo Daza would pull out a guitar, I would pull out a guitar, and we would start singing songs from artists we like. The truth is that I have always done that since I was young. At home, with my siblings, we would sing songs from Gardel, Julio Jaramillo, and Diomedes Diaz. I’ve always done it but now I wanted to do it this way, in a record, as a concept. Sure, there’s always gonna be someone who says: “This is shit.” But man, I like it and perhaps I could’ve done it better, or maybe not, maybe I shouldn’t have done it, but I wanted to. And I did it with love and devotion, you know? We worked really hard with Sebas, and with everyone who was involved in every detail, looking for the best way to find a version of these songs among my music and my way of doing it.

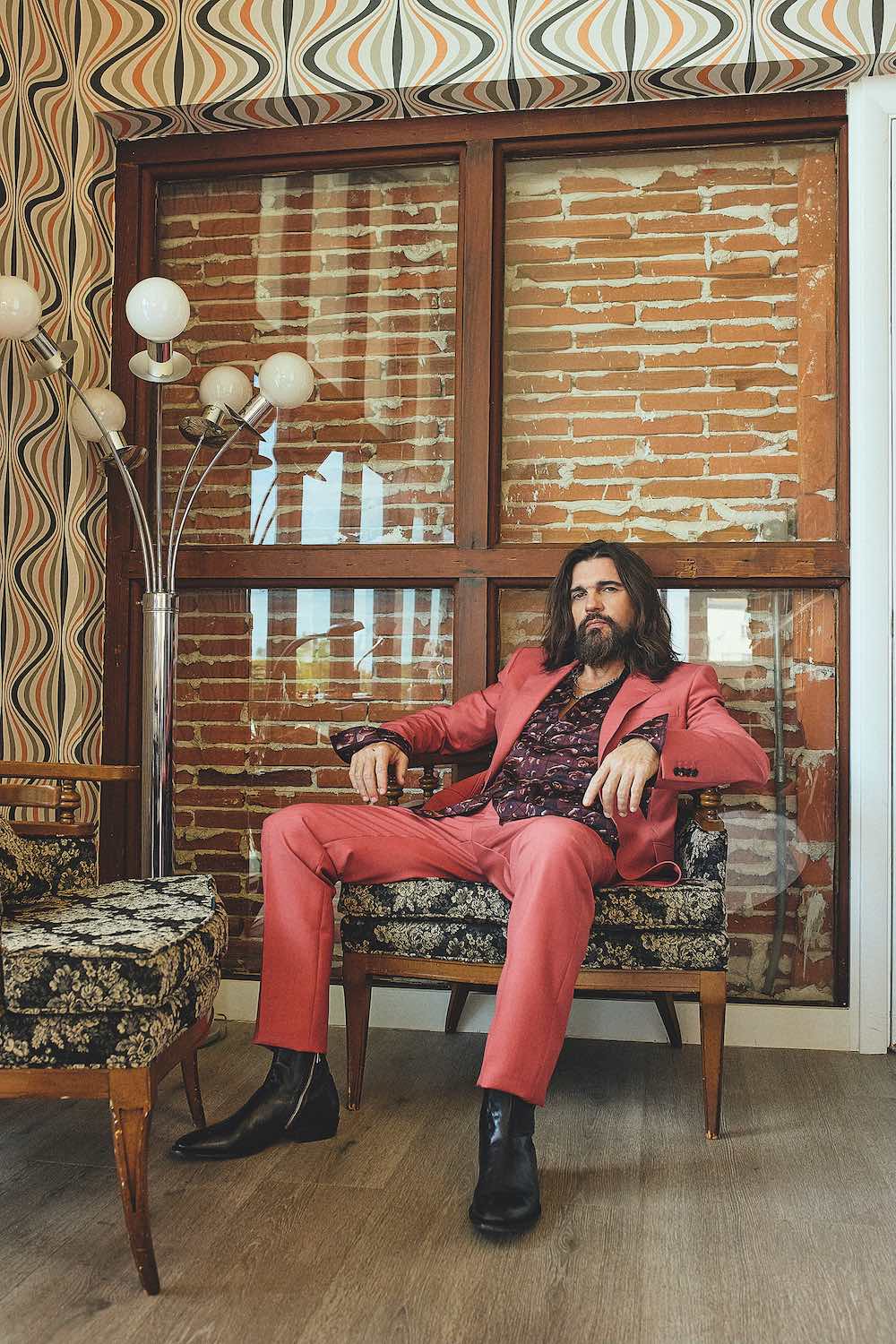

Photograph by Mario Alzate

Your origins define a strong contrast to your beginnings in metal and more aggressive rock…

I lived in a very small world. In the beginning, my whole life revolved around my family, it was a beautiful time. After that, my teenage years coincided with the harsh era of Pablo Escobar’s drug trafficking. The country and Medellín were shaken up. That was the arrival of rock in Spanish, metal, punk, and new wave. I was about 15, and I went from bar music to Kraken, Nash, or Parabellum. Then, some of the songs included in “Origen,” also have to do with that moment. For example, at 18, and even though I was a metalhead at the time, I got my first girlfriend thanks to “La bilirrubina.” And I fell hard! I have never believed in radicalism, all music is beautiful. Besides, music has to do with our roots and the mix of African sounds with indigenous ones, with the Caribbean, the Pacific, the Atlantic, and all our tropical culture.

When did you start to incorporate the nuance that popular music has into your work?

With Ekhymosis we tried a few things – we included congas, piano, and other tumbaos. We experimented with bass lines but their presence was heavier on my first solo album. The percussion also had to do with Colombian percussion, and in some songs, their bass is a vallenato bass. In fact, ‘El Papa’ Pastor recorded it; he also played in la Provincia.

Artistically and creatively speaking, how easy were these covers to make?

Regarding the artistic side, the process was very pleasant; I didn’t feel anxious nor fearful when doing it. Quite the opposite, I really wanted to do it. And I wanted to do it truthfully, exactly as I was feeling it. We made progress since the very first day we began working with Sebastián here at my home. Each day brought its new discovery: “Hey, let’s try this, let’s try that. Doesn’t it sound awesome? Let’s go this way.” We thought about how to sing the songs without imitating them but rather stand from a middle ground. So, in regards to that aspect, everything was great because it was something I really wanted to do, and I greatly enjoyed the process. It was exciting to see how each song would take me back to my childhood in a split second. I hadn’t thought about how they were made. When you record songs, you notice that more clearly. It’s like transcribing a book; you understand everything from a different point of view.

What about the legal aspect of it all?

Some of the songs are of the public domain, as in the case of Gardel’s because it’s been so long. With artists like Joaquín [Sabina] or Juan Luis and some of the others included, Bob Marley for example, we asked for their permission. Then they listened to the covers and everyone loved them. Everything was cool and we moved on. That was the process.

Do you consider it important to have the artist’s blessing?

If you pay homage to someone by covering one of their songs, it would be great if they liked the song when they listened to it, right? But that’s something you can’t know. It’s another cover, there’ll be a thousand more covers besides mine. But it was fantastic to have the opportunity to share and speak about these songs with Ziggy Marley, Juan Luis Guerra, Joaquín Sabina, and Fito Páez. The idea of these versions didn’t happen overnight, behind each song there’s a story. Gardel was my childhood, and I met Fito 20 years ago, we developed a great friendship that helps things happen in a natural way.

How did you feel going back to making an album with an analogue base where there are so many instruments? How do you go back to something you developed so much in the past, but suddenly stopped exploring in the last decade? How did it feel to go back to the instrument?

Good, man, great. I believe this album marks a path, a new direction I’m heading for a while, maybe for the rest of my life. What I did in “Mis planes son amarte” and “Más futuro que pasado,” was phenomenal. I really liked everything I did there. I had the opportunity to work with many artists without feeling completely comfortable, I was in a place I wasn’t 100 % myself but I learned a lot from there. I thought that was a really cool way of seeing music, it’s a different world. To have been able to explore those sounds was very cool but in the last record, that was kind of my limit – I don’t want any more of that, and I can’t, I’m not interested. What I mean by that, is having to make music that has to do with a specific format, like radio. This album connects me to what really moves me. Music moves me, and it’s not that I don’t like what I did, I do like it. But not everything you do is fine, there are things that aren’t right, even for myself. I’d say: “I would’ve changed this, I would’ve changed that.” That’s inevitable, or at least in my learning process, because I keep learning. And I make mistakes and I’m sorry about that. Then I’d say: “Fuck, it’s great that I made that mistake because if I hadn’t, I wouldn’t be where I am today.”

Besides, you learn a lot from people. People are amazing, no matter their age. So, I don’t think any genre is better or worse than another. Some need certain things and others need other things. In the end, I felt this was what I had to do, what I’ve always loved, rock. This doesn’t mean that I’m gonna put my Caribbean part aside, everything that I like such as vallenato, merengue, salsa, and even reggaeton.

The guitar is the protagonist of this record and referring to the last decade, the industry’s trends might have pushed you away from it. Now you come back with an album full of guitars.

Yes, when “P.A.R.C.E.” came out, it was a very dark time of my life, creatively speaking. And I realized those are the kind of things that are meant to happen. Then, with “MTV Unplugged,” that was an album in which, somehow, I came back to that organic part with Juan Luis. It was great, it was very nice. After that, “Loco de amor” was also an experiment with Lillywhite. And I made “Mis planes son amarte” with Sky, Mosty, and Bull Nene. It was great but after all of that I said “enough.”

I really want to make the music that I love, the music I feel comfortable and calm with. During the pandemic, I’ve written like a mad man. Clearly, I made this album about a year ago, so after all this time, I’ve studied and got in sync with everything. Besides, I’ve started to visualize the road ahead, from now on, everything is different for me. Now it’s about what I can naturally do better, and do it well, which is singing and playing guitar.

Do you think that, at times, that exploration of the urban sound has more to do with pleasing new generations and being on the trend? And the industry might push artists there but some do well, some others not so much.

Yeah, but I don’t criticize that. I can only speak from my own experience, and I can’t judge other artists just because they’ve done it. Sometimes it’s hard to shut all the noise that’s taking you there, you know? It’s unavoidable because it’s also an opportunity. Why not do it? Why not try and work with other people who have nothing to do with me? That’s another way of making art. But, you could also stay in the middle. Not here, nor there. There are artists who do it and love it, but you have to have an attitude to do that, to make reggaeton. That’s why they do well and succeed because they are honest. But there were other things that took me there.

I love Kanye West and I think everything he does is fucking fantastic – his music, how genius he is as a producer. I love hip hop and trap, I always listen to Post Malone and I think he’s great. So I didn’t say no to that. I have three teenage children who are listening to that all day long. I listen to it, and at this moment of my life, there’s no room for radicalism. Right now what I want to do is sing better, play better, compose better, and if I can do it with people who enjoy it like me, man, I’m happy. But thinking about the race to the number one spot and reaching the radio, that’s very hard. When it happened to me, and at the time it happened naturally, I didn’t think that came with the songs. The way I see it, music changes and it’s cyclical.

Photograph by Mario Alzate

Seeing how the industry is right now and where is heading, do you think this album represents a statement of artistic principles for you?

Yes, I believe this record connected me with my essence and my past. I missed the guitar, the drums, playing with people. I needed to feel music’s force and above all, organic music, that’s for sure. And I don’t do it as a form of protest to today’s industry, no, but it’s just what I wanna do right now. Maybe I’ve wanted to do it for a long time now, and this was the moment. But I would hardly put out a song with a beat or a dembow again, not because I don’t like it, I just don’t think that at this point in my life I want to do that again.

What do you think was the determining factor in leaving the urban sound behind and more so when it’s still a trend?

Well, the first thing is that when we now talk about urban music, we’re talking about pop, the mainstream, to be honest.

Sure, but “Origen” doesn’t necessarily go out of those parameters, it’s still a pop record…

But I’m not in any of those trends. I’m making a concept record.

But it’s not necessarily not pop, “Origen” is still a robust, rock and roll record, full of organic power. It can still be mainstream and pop if you take it there, right?

I don’t know, I don’t know what else can happen to this album. I knew this is what I wanted to do now, and I did it with much love. That’s what I am right now, and people who know me know that I’m like that. This sets the tone for where I’m heading with new music, without saying that that’s how my future songs will sound like. The naturalness of playing guitar, singing, and exploring sounds even more, definitely makes things different.

So you don’t like urban music and a more digital production anymore?

It’s not that I don’t like it anymore, I love it. I just want to do something more organic. For example, my daughter Luna loves music and she goes to Splice.com and downloads her samples. It’s fantastic to be able to do; you download kicks, snares, hi-hats, basses, guitars, whatever you like. After that, you can modify it, change it, it’s a never-ending thing, and that’s a different way of conceiving music. Not from the instrument, but in a different way. It was completely foreign to me but now that I understand it, I appreciate it and I like it. There are productions made like that that I really like – Frank Ocean, Tyler the Creator, I love all those textures. On the other hand, I’ve had a guitar since I was seven. I like Los Panchos, Los Visconti, Octavio Mesa, Metallica, you know? [Laughs] I’m a country person and I love it. I love rock, I love metal and I’m a bit obsessed with it.

Did that change in direction arose from nothing? What triggered it?

It’s just that some really cool things started to happen, man, without planning them. Things like the show at Rock al Parque, moments that somehow brought back fond memories. I really needed to go back to that place. And I’m kind of on that road. Before covid, I started thinking that I wanted to make the music that I like to make. And if people want to hear it, great, if they don’t, it’s also okay. There are all sorts of options out there. I don’t want impositions, nor do I want to compromise to anything specific, I want to be free. When I walk into the studio, I have no fucking idea what I’m gonna do, no clue. I just turn on the computer, pull out my guitar, and all of a sudden I have an idea, and I start developing it and it has a little bit of everything.

I share your idea that music is cyclic and although reggaeton prevails and keeps on being the number one trend, don’t you think that things might be changing and that analogous, organic feeling is gaining strength again?

Yeah, I feel that way, maybe due to my age or because it’s my reality. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with today’s music, it’s part of a trend, but I feel that there must be more innovative music so it’s not that repetitive. At a certain point, everything sounds the same. And when someone like Rosalía nails it, people get surprised. Or what happened to C. Tangana, he nailed it as well. As Balvin or Bad Bunny did at their time, you know?

This kind of project comes at a certain point and simply nails it. On the other hand, rock concerts are the best thing there is. Watching bands like The Strokes or fucking Metallica live, that’s nuts. The drums, the guitar, that hard sound – that’s a very brutal attitude. And I think there will never be an end to it, no matter what people say, it will prevail. People love rock or reggaeton, or just simply music that makes them feel better according to the mood they’re in. And that’s okay. The worst thing that can happen is that there are barriers in art, that’s awful to me.

There’s something very important in this record and it’s that beyond your influences, not every artist has the ability to make a ranchera, rock & roll, pop, tango, salsa. How do you do that? Because apart from needing a giant artistic ability, it’s quicksand, it’s very difficult.

Well, it’s what I’ve been telling you. As a child, I only listened to popular music with my family. At school, all the girls were head over heels over Luis Miguel and Menudo, and I didn’t even know who they were. I didn’t understand, I lived in another world. My first concerts were Los Chalchaleros, Los Visconti, Totó La Momposina, Joe Arroyo, Diomedes Díaz, Octavio Mesa, Julio Jaramillo – those were the people I looked up to. That was my algorithm, everything I did with my family in Carolina del Príncipe. In high school, I listened to my first metal album, “Sabotage” by Black Sabbath. My sister’s first boyfriend gave it to me. He also introduced me to “Mujeres” by Silvio Rodríguez. Then AC/DC, Rush, Yes, Bruce Springsteen. Can you imagine my friends Felipe Martínez, Federico López… talking about Kiss and Slayer, and I had no fucking clue what that music was about. But when I discovered it, I said: “This shit is fucking good,” and I got hooked on it. And I’m still are. That must be the reason why I try so many different things. So here we are, talking shit.

How do you see the present situation in Colombia? It’s nothing new but every year it explodes in a bigger way.

Colombia is in a critical, increasingly violent, and out-of-control situation. What began as a righteous cry from society, asking for social justice and more opportunities for everyone, is becoming an increasingly dangerous and bloody mix from where we will not be able to come back from if we don’t stop to think and reflect. The system has long been rotten and this outburst is a consequence of that unequal history that we have lived since our birth as a republic.

In Colombia, we have been led by the same political trends and the same families for over 200 years. When do you think it’s time to give change and social, progressive, liberal policies a try?

Things are not gonna change overnight. Changing an entire system will take years. Opening the door to education and social awareness will take entire generations, it’s not something just for the current government. It’s part of a whole transformation of the conscious society, and that’s gonna take a long time. We have to take care of everyone, take care of companies that encourage development, take care of wealth generation and not wealth accumulation. Colombia requires a real connection that summons many to overthrow hate and divisions in order to give Colombia a common purpose.