Jesse Lizotte*

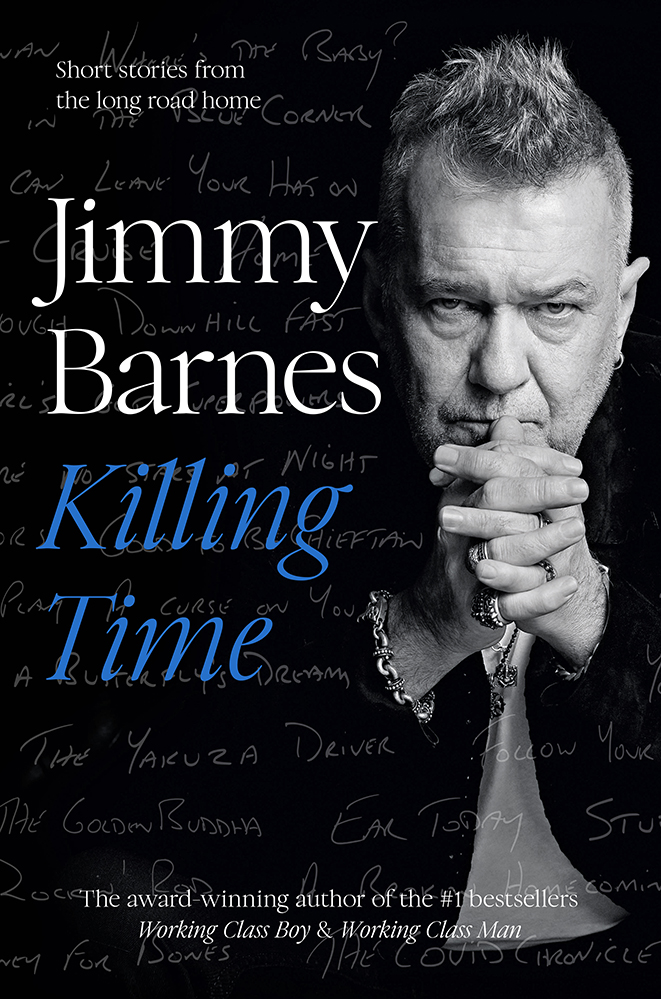

Releasing his third book, 'Killing Time' sees Jimmy Barnes looking back on life's precious moments via a series of charming, witty, and heartbreaking short stories.

When Cold Chisel first emerged out of Adelaide’s northern suburbs in the early-to-mid ’70s, few could have imagined that over 40 years later, their soon-to-be iconic frontman would one day become a bestselling author.

However, that’s exactly the story the public were reading in 2016 when Jimmy Barnes unleashed his first memoir, Working Class Boy. Recalling the events of his childhood between Glasgow and Adelaide, the book was a truly special affair. Emotional, heartfelt, and harrowing, it told a tale that even the most dedicated fans of Barnes and Cold Chisel could never have guessed.

Winning the Biography of the Year at 2017 Australian Book Industry Awards, it was followed up soon afterwards by the release of Working Class Man. A sequel to his first memoir, Working Class Man picked up where Working Class Boy left off, and like his first foray into writing, won another Biography of the Year honour at the ABIAs, making him the first author to win the award twice.

From a logical point of view, the Jimmy Barnes story has now been finalised, with Barnes – one of the highest-selling Australian artists in musical history – having painted the picture of his life across the canvas of the written word. But as the man himself could attest to, old habits die hard, and it didn’t take long for him to again retreat to his desk to pen a new book.

Titled Killing Time: Short Stories from The Long Road Home, Barnes’ third book is his first collection of short stories, and features the same immersive storytelling that readers and music fans have come to know him for. Ranging from charming, to witty, to entirely heartbreaking, the tales are brief snapshots into one of the most storied and accomplished lives in Australian music, and offer readers an insight into yet another side of Barnes.

In anticipation of the book’s release, Barnes spoke to Rolling Stone to discuss how Killing Time came to be, how his writing has humanised him in the eyes of average Aussies, and what the future holds for his writing talents.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

I’m going to go out on a limb here and assume that five years ago, you probably had no idea by this point you’d have not only released two critically-acclaimed memoirs, but that you’d be gearing yourself to release a third.

I wouldn’t have thought I’d have the patience to sit and write a book, or, not the inclination, but the ability. When I wrote that first book, I felt like I was writing it for myself, so it was one of those things where it was more like therapy than anything else, and I just had to write it and get it out. During the process of doing that, I discovered that I enjoy just sitting at my desk and writing.

And I liked the fact that after a career of – I’ve said this in interviews before – looking out and always judging myself on what other people think of me, to just sit back and look in, to look at my life, look at my feelings, and look at them from my perspective rather than trying to impress people, it was just a really great thing. And I felt like it gave me an incredible period of growth to sit back and do that. So I just enjoyed doing that, and now, I like writing all the time: I’ve finished this book, and I’m onto the next already.

Had you always thought you’d one day look inwards and do a memoir, or was it a more recent decision?

Never. I mean, if you’ve read the first book you’ll see I spent most of life trying not to look in – trying not to look at the past, and trying not to look back. I just wanted to keep moving, and if I could just keep one step ahead of my life, or one step ahead of my past… There was a lot of stuff that, as a child, was too dark to say, and as an adult, I was too affected by that childhood to deal with, and then that caused a lot of behaviour that, as a responsible adult, I wasn’t ready to face either.

So it was a constant [need to] stay one step ahead of myself, which, as anybody knows, if you’re running from something, eventually you’re going to trip, or it’s going to catch you. Eventually, you do have to stop and turn and face it. That’s the only thing you can do. Or be run over by it.

“I wouldn’t have thought I’d have the patience to sit and write a book.”

But I actually thought that I could avoid that for as long as possible, but it became more apparent to me that, as life got on, I couldn’t outrun it. I started getting some therapy and I started talking to people, and I literally started writing the book to just get these ideas out.

I thought that if I could just write it down, I could let it go, but the process of writing it down, the stuff that was obvious in my head, it opened up a can of worms because it was a whole bunch of things that not only had I not wanted to look at, but there was stuff there that was so traumatic I’d sort of blocked it out of my mind completely.

It wasn’t until I sat down and started talking about something else related to it that all these dark things – abuse and all that kind of thing – came out. So that’s when it got really tough, but it was also really liberating; I started to feel like I could let go of some of this baggage I’d been carrying around my whole life. The process of writing has been a gift.

There’s obviously a lot of heavy content being covered in the first two books, while this new one is a little bit different. It’s been described as a collection of “tall tales and B-sides”, but we all know the B-sides are often more important than the single itself. So what was the thought behind this book? Was it a case of that you still had more to say and tell people? Or was it a case of these are stories you couldn’t quite fit elsewhere?

It was a bit of both. I read a lot of short stories, and literally sitting on my desk at the moment, one of the books I’m reading at the moment is Portraits and Observations by Truman Capote. I like short stories because you can put them down, walk away for a month, come back, pick it up, and read again. I like the idea of it, and once again it goes back to that idea where you paint a picture, it’s like a different art form.

Writing long-form is much different to songwriting. Songwriting, you’ve got to get your whole story in over in four main lines of the chorus, most of the time, unless you’re Bob Dylan or Don Walker. But as a songwriter, you generally go by punchlines, and writing a story that’s as short and concise as possible. Writing a short story allowed me a bit of both. I could be concise, I could say a lot in a few words, and you could get to the point, and sometimes that point is dark, sometimes it is heavy, and sometimes it’s just funny. It’s just life, parts of this book is just my observations on dealing with COVID, because that unfolded while I was writing the book, unfortunately.

But it’s just a different style of writing, which I quite enjoy, and I like the fact that I could put a story to bed, and it’s like clearing the palette, and then start again with a whole new canvas. So it’s a good way to write, but in saying that, I’ve got a few other projects up my sleeve that I’m writing, but my main thing I’m trying right now is more long-form. Either more non-fiction, but I’ve also started fiction now. I started writing a few stories.

Well short stories seem a little bit more appropriate since people have much shorter attention spans these days. It almost feels as though this book is more suited for this day and age, in a way.

I didn’t think about it much, but if I had to get it down to 136 characters, or whatever it is – on Twitter – it would’ve been a different thing. But people don’t have a lot of spare time. It would be an interesting way to write a book; keep it all down to one tweet, each story. But people don’t have much spare time, and like me, when people are on the go, it’s good to be able to pick something up and not have to go, “Oh shit, where was I?” and go back two chapters just to catch up on what you were thinking.

So it’s good that you can pick it up and start a story fresh. I really do like reading short stories – it’s a good form for me. I do have the attention span of a soap dish [laughs].

Were all of these stories ones that you sort of had in the forefront of your mind? I know a lot of musicians talk about how they don’t remember a lot of stories from their past until they were prompted years down the line, but these all read as if they happened just yesterday.

These were all pretty much burnt into my memory. I mean, there’s a lot of others that popped up as I was doing these. Some stories are great on the day, but they don’t really relate when you write them down or tell them back. I didn’t write down a lot of stuff and edit it out. These are all stories that I’ve told at parties, or I’ve spoken to therapists about that I wanted to write, and to acknowledge the help I’ve been given, or friendships, or when someone has pulled me up and told me the bleeding obvious, like I have to pull my head in, or whatever. There’s things in there that are like lessons of life for me as well.

Everyone sort of looks at Jimmy Barnes as a hard-living monolithic creature of rock music, but you look at these stories, and they totally humanise you. They puts you on this level where the reader goes from reading about Jimmy Barnes the myth to Jimmy Barnes the man. Was that something you had in mind at all?

I guess one of the things you try and do – and I didn’t intentionally do it, but I guess that was fine, also – is that you try and show people that rock and roll is working; it’s a job that we do. And as much as we love it, there’s a lot of schlepping and busting about until you get to do the bit of work that you love. And that’s basically the title, too: Killing Time.

So many musicians have said, and I think Charlie Watts said famously in an interview with Rolling Stone 25, 3o years ago that he spends 22 hours a day twiddling his thumbs, waiting for that hour-and-a-half, or two hours where he gets to do what he loves. That’s what musicians do, and I wanted to sort of normalise rock and roll; it’s not glamorous. What’s glamorous, what’s great about rock and roll, is that connection between yourself and the audience. When you get on stage and the lights come on and you strike a chord that resonates with the audience, and you feel that connection, and then you go on and you’re inspired and you make really great music, or you have an incredible performance, that’s what drives a musician. It’s not living a glamorous lifestyle.

“I’m living life, I’m not just waiting for it to take me out, or, in a lot of cases – and in my case – taking myself out.”

I didn’t become a rock singer because I wanted to be famous, I became a rock singer because I love music, and I just wanted to point out that underneath it all. I mean, there’s stories about glamour and Orient Express trains and stuff like that, but it’s more about the day-to-day, getting through life, dealing with children, looking at your own fears – things that happen in life while you’re trying to get through the day. That’s what we have in common with everybody.

When you think about that, if people realise we – rock stars and singers and all that – are more like them, and that coming together that we get when we get to a show, is what makes us both… Y’know, they walk away saying, “That was a great show,” and I walk away saying, “That was a great show.” That’s the moment that has made us, that’s what’s making us great; the joining of the two of us. It’s not just me being up there singing, it’s that moment where we all fall into place together that it works. The rest of the time, we’re just like you and we’re trying to get through our day – sometimes it’s easy, sometimes it’s hard.

I guess that’s one of the things I was trying to do with these stories. That’s why they go from talking about fear, to talking about hope, to talking about having a laugh at yourself, or taking a look in the mirror and saying “I don’t like who I am.” Or feeling yourself grow, and change, and getting better. That’s the thing that normal people do.

One thing you see from looking at the book is how you seem to view life as being far more precious these days, which obviously goes against the idea of killing time in-between those moments.

Yeah, and I think I say at the end of the book, “I’m not killing time anymore, every moment is precious“. Before, you would be [killing time], you’d be sitting there, tapping your fingers, looking out the window of a car that’s driving at high-speed where the driver is nodding off at the wheel because you’ve got to get a thousand miles to your next gig.

Now I don’t just sit there, I look around and I’m saying, “There’s things to do, how can I help? What can I do to make this better?” I’m living life, I’m not just waiting for it to take me out, or, in a lot of cases – and in my case – taking myself out.

Ironically, you haven’t really got that much time to kill anyway since you’re always writing books now.

Well this is the best way of writing, to kill time, for me. Because not only do I get there and it entertains me – because you think back and go, “Oh shit, I remember that!” – but it’s also like therapy, it is giving things I can share… You know, sometimes it is easier to write things down than it is to say them. I’m a person who, I’ve kept things close to my chest for most of my life.

It’s strange, because I’ve been in the media, I act like a lunatic and all that, but the stuff that really mattered most, I kept close to my chest, and writing these books has allowed me to get things off my chest and share them with the ones I love and the people that you deal with everyday, and the people you see on the street.

I used to walk down the street and people would try and drag me to the pub to get drunk. “Hey, Barnsey, come here, fuckin’ drink this!” These days, they don’t do that because they know there’s more to it now. I’ve noticed they’ll talk to me more about kids, or they’ll talk to me about music. It’s not just like, “Hey Jimmy, let’s get fucked up,” y’know?

Well that’s sort of how I mentioned before in the way the book provides this other side of you, and it humanises you, and it gives people that different look at who Jimmy Barnes really is.

But not only does it let other people look at the other side of me, it’s letting me look at the other side of me. That’s the really good thing. It’s the process and physically doing this… I’m growing as I’m doing it because I can only show people what I realise myself now. If I can see good or bad in myself, or see change in myself, then other people can see it. So the process has helped me to grow rather than just allow me to share that growth.

You also noted before you’re already looking ahead to your next writing project. Are you hoping to continue in the same vein as this, with more stories about your life, or will you focus more on – as you said – fiction?

I’ve got two stories up and running which are fiction, almost like horror stories, but they are based on life as well. I’m not sure if they’re going to end up being full-on sort of novels, or if they’re going to be short stories. It’s early days in the process, but I think I’m just going to play it by ear. I like the idea of… I mean, writing long-form for the memoir is really great because you really have to think about the pictures you’re painting.

It’s sort of like a different art-form and you really have to think about the dialogue and how people communicate and what people feel. You’re not getting over it to get to the chorus or the punchline, like in a short story. I do like the long-form writing because it makes me think and it makes me feel, and it makes me think about how I should be processing life, so I’m tending to lean towards that long-form, probably fiction next time.

By Christmas next year, Jane, my wife and I, are also doing a cookbook. I’m going to write stories, short stories for each recipe, so that’s going to be an interesting collaboration through life and love and hope, and all sorts of things.

Jimmy Barnes’ Killing Time: Short Stories from The Long Road Home is out now via Harper Collins Publishers Australia.