Emma Wallbanks

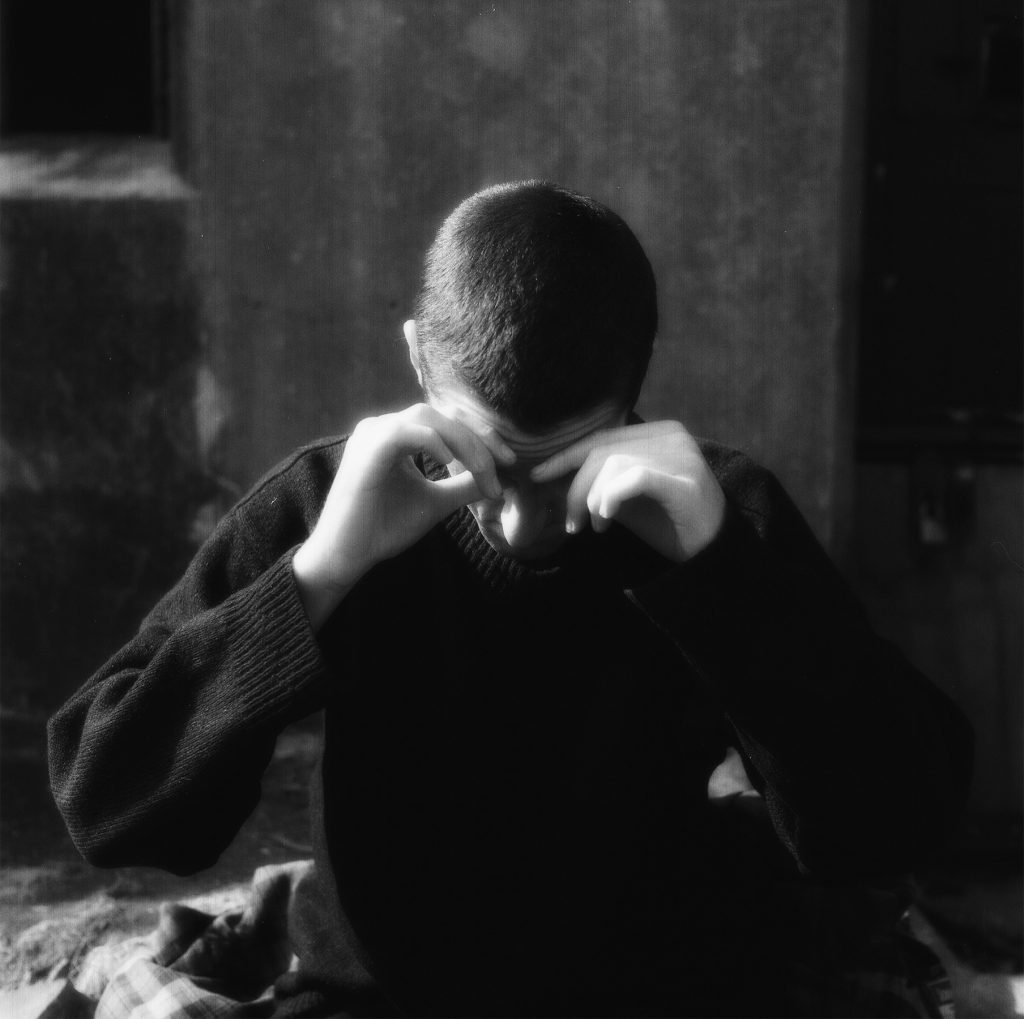

Ben Woods contemplates the future in the face of his nomination for Alternative Artist of the Year at the Aotearoa Music Awards on November 10th.

It’s a hot spring afternoon in Canterbury with the northerly winds gusting, and Ben Woods is nowhere to be found. After spending a Sunday morning recording vocals in his Lyttelton studio with Lucy Hunter of Opposite Sex for a new project, Ben and Lucy are partaking in their traditional swim in the brisk waters of the South Pacific before she begins her five-hour drive back to Dunedin.

Ben’s second studio album Dispeller has been out for only a few months, but it has already garnered critical acclaim and earned him a nomination for Best Alternative Artist at the Aotearoa Music Awards on November 10th. The album was featured in international arts journal The Quietus and New York magazine The Fader. Radio New Zealand praised Ben’s self-awareness and “intentionally jarring sound design”, which lends the album a haunting sense of space that reaches through time.

We had planned to meet in Magazine Bay, the first of the bays that snake along the coastline of the harbour towards Banks Peninsula. But technology, often more of a hazard than help on the South Island, has instead led to an industrial naval shipyard, where coils of barbed wire top chain link fences. A couple sit in lawn chairs, staring out at the blue water. There are a few boats in the water but no musicians. A man with white hair descends into downward dog in the grass.

Ben’s dog Poe, a 10-year-old black and white heading dog, bounds out of the car. Ben leans over Keno, a terrier not yet two, and carefully fastens him to his lead.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

We walk on strange lands. The hill we ascend is on the rim of the crater of a volcano that first erupted eleven million years ago, part of which has been flooded by the sea. Poe races ahead, eyes wide and tongue plastered back in the wind. Keno strains at the lead. At its crest, two roads diverged in the green wood. Straight ahead lay Corsair Bay, where Ben was born twenty-nine years ago, just around the corner from where he recorded Dispeller in Lyttelton. We veer left and descend down wooden steps.

The landscape where Woods grew up and still lives inhabits his sound. Synths shimmer like the emerald green water in the harbour. Time moves so slow in Woods’ music it almost seems to pause, and so too does the pace on this side of the Lyttelton Tunnel.

Emma Wallbanks

It’s the day before Halloween. A man with a potbelly hovering over his board shorts stares up at the trees stretching out over the water. A few of the brave wade into the water, arms outstretched. We settle at one of the two picnic tables where Ben’s partner, the poet Rebecca Nash, is smearing sunscreen on her eight-year-old daughter, Noelle.

Lucy stares out at the water. “I only ever go swimming when I’m with Ben.”

Lucy moves carefully into the sea next to Nash. Ben wades into the ice waters behind them, holding Keno in his arms.

Nash looks at the odd couple. “Why don’t you put him in the water?”

“He’ll leave us,” Ben protests.

Ben gently releases Keno, who swims straight to shore and then turns back to stare at us, incredulous.

“We just have to go for it,” Nash says to Lucy. “One, two, three.”

They disappear in unison beneath the surface. The rest of the beachgoers watch from the shore, unwilling to brave the sting of the Antarctic current. But Ben Woods goes a bit farther than those around him.

The next day, we agree to meet in Ben’s studio in Lyttelton, an industrial port town that sits perched on the inner edge of the western rim, a fifteen-minute stroll along the bays. Samuel Butler dismissed Lyttelton as “scattered wooden boxes of houses” in 1860, ignoring the marvel that they sit within alternating grey and red rocks that bear signs of the lava and ash that once flowed past. It is said by some that in cold weather, steam can be seen rising from the ground.

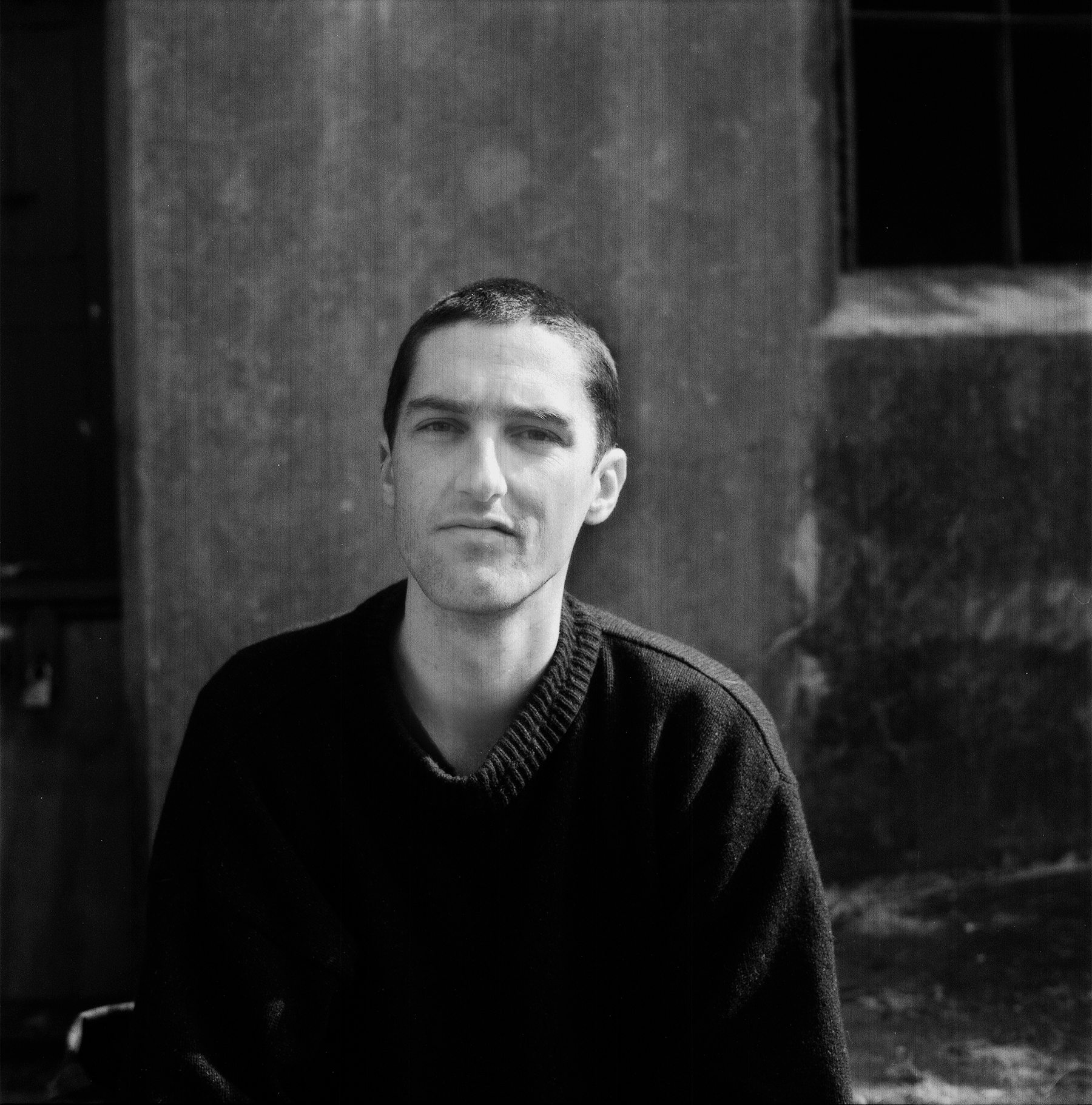

Hahko

Ben picks up one of the several acoustic guitars strewn on the floor of his studio, a small wooden box with windows overlooking the single road that Lyttelton calls downtown, and strums it as he walks around. He’s about to record his next album and is in the midst of a few other projects, though he’s unsure where those are headed.

“I try to keep it quite short term,” Ben says. “Which could be my problem, maybe. But I try to focus in on what’s relatively close to me.

Dispeller was recorded down the street at the Sitting Room with Ben Edwards, who has also worked with other Lyttelton musicians in the alt-country scene such as Marlon Williams, Aldous Harding, Julia Jacklin, and Delaney Davidson. The rich musical history of the South Island saturates Dispeller. Williams loans his vocals to “Wearing Divine”, as does the Dunedin rock legend Alastair Galbraith on “Speaking Belt”. Not only the landscape but the port town too can be heard in the sounds Ben makes. The scratching freneticism of the guitars mirrors the industrial chaos of a port at night. The amplifiers sound ripped open, as if Ben had stumbled on the secondhand gear of the guitarists who pioneered distortion.

Many of the musicians that contribute to Dispeller first met at the darkroom, a small box of a bar on the outskirts of the four avenues that border the city centre of Christchurch. In October 2011, it was one of the first venues to open after several thousand earthquakes led to the majority of Christchurch’s buildings being replaced with gravel lots. Started by two musicians who paid bands a guarantee to play for free, the darkroom quickly became an indie rock hub, showcasing the flourishing rock scenes of both Christchurch and Dunedin. The filmmaker Martin Sagadin, who directed many of Ben’s music videos, including the short film that accompanies Dispeller, was working behind the bar.

Martin recalls being taken by Ben’s first solo project, Fran/Bar Group. “I actually started following them around and filming them because I thought they were a really fascinating band.”

It was at the darkroom that Ben first saw Lucy “scream” in Opposite Sex.

“At first, I was kind of scared of them? Like, I was almost angry at how intense they were” Ben laughs. “But it turns out I was wrong. I just really liked the band and was afraid of how confronting they were. After that initial shock, I became obsessed.”

“The people around you are a huge source of inspiration,” Ben muses. Ben has played on and off in both Wurld Series and Salad Boys, whose main songwriters are Luke Towart and Joe Sampson. “I play guitar sometimes and I can tell, ‘Oh, I’ve gotten that from Luke’, or ‘That’s Joe.’”

“Shall we get a beer?” We head down to London Street for a drink.

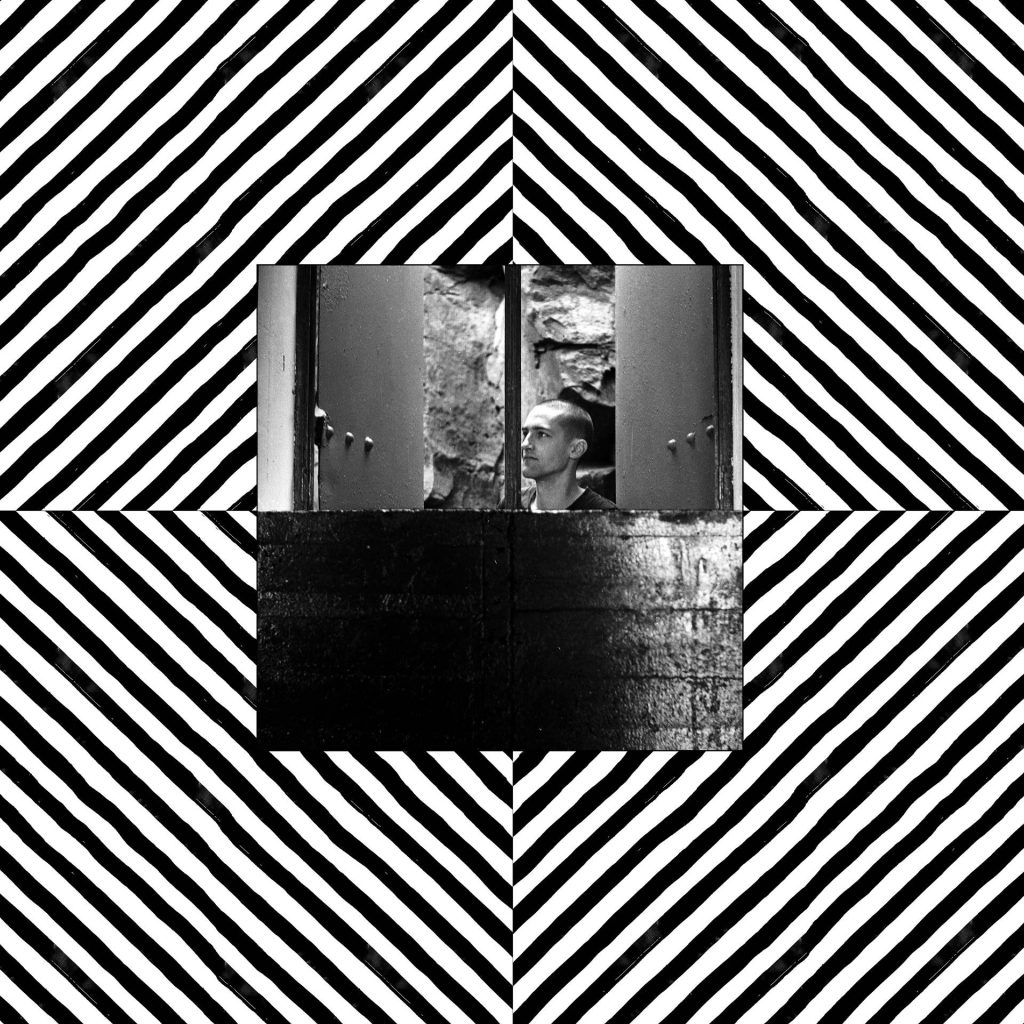

Emma Wallbanks

Today, on Halloween, the water is a sea foam green, the sky above it overcast navy.

Trick-or-treaters are rare up the winding road in Lyttelton where both Ben and Luke live, shielded by trees. But on London Street, children in costumes spill out onto the street corners. Ghosts wander by in a clump.

A woman holding a small girl in a unicorn onesie nods at Ben. We make our way over. The two are planning a festival together that Ben hopes “will use industrial spaces and give an authentic experience of Lyttelton” and provide opportunities for artists to collaborate. Her husband, Richard Larsen of Glass Vaults, smiles across the street. He comes over and greets his daughter by gently pressing into her forehead. “Have you heard Richard’s band, Crush?” Ben says as we walk into the bar, past a woman wearing a Mardi Gras mask carrying a broom.

Emma Wallbanks

According to pop culture scholar Simon Frith, rock music constructs only imagined communities, like that of a rock boomer feeling a sense of belonging from falsely “remembering” Woodstock. However, in contrast to what the romanticised accounts of music-making in “isolated” places such as New Zealand might suggest, nothing about the music made here takes place in isolation.

“We’ve done a lot of things in exchange,” Martin recalls. “I’ve done music videos for him and he did my film [Spring Interlude] for me. The first couple music videos, often they would be done on tiny budgets. We were just working with exactly what we had: whatever camera was available to us is what we used. We would split it: you pay for the gas, I pay for the food or the booze.”

To have both a short film and an album of the same title is very odd and an example of Ben going farther than those around him. Director Martin Sagadin explained that the idea was formed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic as a concert film that people could enjoy during lockdown. But the project took so long to come to fruition that the world had opened up by the time it came out, and the plan lost its context.

Nonetheless, Dispeller—both the short film and the album—remains a love letter to a time and a place, showcasing what Alexander Pope called the “flow of soul” among the South Island rock musicians. In the short film, Luke Towart plays a simple bass line and manipulates a 70s tape machine. Lucy Hunter sways in a country dress. Country musician Ryan Fisherman harmonises through a yellow telephone. Ben Dodd and Rory Dalley are there too, providing the same steady presence they do to a myriad of Christchurch projects.

Although tall and thin, Ben Woods also seems deeply grounded. His nature is dreamlike and pensive, connecting him to the other poets and writers who have inhabited Aotearoa and created within the Pacific Ring of Fire, aware of both their power and limitations. Graham Billing called man “a shadow on the landscape” of New Zealand, writing in 1966, “These hills and mountains, even the harsh and level plains, seem to shrug off human conquest.”

“I’d really love this to succeed in regards to giving my ego a pat on the back,” Ben admits. “But I feel like as soon as that comes up, it feels like I’ve taken a misstep. All the people I admire—artists I mean, and as well as like a lot of friends—they are so certain they want to nurture that beautiful and present part of living where you are just with these people and inspired by them and it’s all as valuable as anything else could be, no matter how much, like, success whatever, that measures.”

Yale professor Jake Halpern lamented in his 2007 book Fame Junkies that the equal attention people once received in tribes had been replaced by one-way, para-social relationships that played out between Americans and pop culture via magazines and the television. Yet in the small indie rock communities in Christchurch and Dunedin, the culture brims with genuine connection. Attention is not focused in any particular direction.

“There’s a song on my album called “Fame”,” Ben muses as we sip tea from op shop mugs featuring rhinos and dogs in the kitchen of his home on the east side of the crater. The title of the song bemuses him, he admits. “Why did that come with this, what I’m hearing?” Ben pauses, as if lost in thought even between words. “It’s more of an expression about how we might see ourselves in our own insular, magical worlds and have a distorted view of something…”

Nash calls. It sounds like Ben is on dinner. “I have…” Ben pauses and looks at the change in his hand. “$2.20. But I’ll be fine with what I have. I’m sure I’ll make it work.”

Before Ben drives me home through the tunnel, he strides into the supermarket across the street and selects one pack of dried spaghetti.

Two dollars, the cashier said.

Ben sets down a single gold coin and thanks him.

It seems whatever the future holds for Ben Woods, it is unlikely to move his centre. Ben embodies something New Zealanders have remembered but the rest of the world has forgotten: that one’s attention belongs in the present, and what he already has will work for him.

Dispeller is out now on Shrimper (USA), Melted Ice Cream (NZ), and Meritorio (EU/UK).