Jacob Boll*

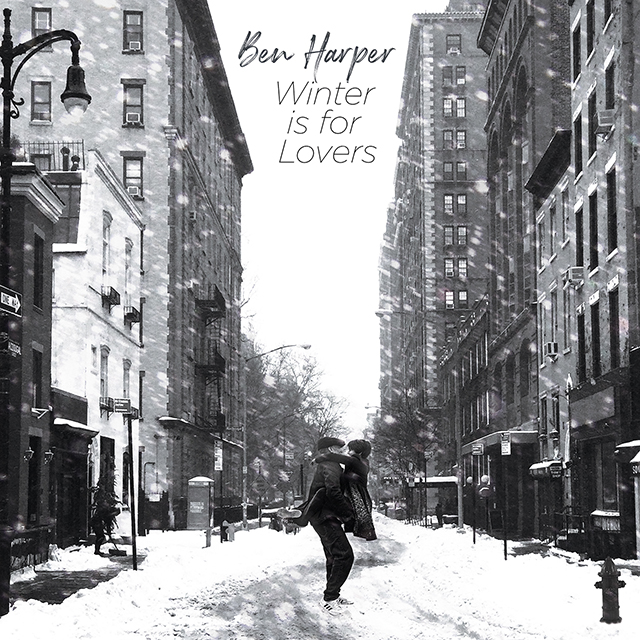

Releasing the first wholly instrumental album, Ben Harper has utilised a lifetime of musical influence to create a groundbreaking body of work.

When Ben Harper last released a studio album by way of No Mercy in This Land, his 2018 collaboration with Charlie Musselwhite, one could have easily assumed that his next record could once again see him expanding his palette by way of another collaboration with an iconic blues artist of Musselwhite’s calibre.

Few, however, might have expected things to go the other way, with Harper’s 15th studio album breaking entirely new ground for the acclaimed musician.

Announced in early September, Winter Is for Lovers serves as something of an important milestone in Harper’s career. In addition to being his first solely instrumental album, it is described as a “culmination of his entire musical life”, with the only instrument heard on the record – his Monteleone lap steel guitar – being an instrument whose history is deeply ingrained within Harper’s DNA.

Having begun his musical life at a young age, it was his grandparents’ store – The Folk Music Store, in California – that helped provide Harper not only a lesson in listening to, learning, and appreciating music, but allowing him to meet numerous icons of the world of music.

Winter Is for Lovers serves as something of a continuation of his musical upbringing, exploring the American Primitive movement, while featuring references to the blues, Hawaiian, and classic guitar masters he gravitated to in his mother’s record collection.

Composed whilst he was reading Infinite Jest, Harper utilised David Foster Wallace’s method of fusing together short stories to creative a larger narrative in much the same way, combining a series of works named after or inspired by location around the world to craft an album which holds an immensely special place in his heart.

With Winter Is for Lovers out today, Harper spoke to Rolling Stone from The Folk Music Store about his new record. Between handshakes with patrons, and the sound of guitars being plucked and strummed in the background, Harper describes the creation of this stunning body of work, and how it could possibly be the first of many instrumental collections still to come.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Firstly, I want to extend some congratulations for the new album. It’s a really special record and something you must be feeling really proud of.

Thank you for taking the time to talk, and thank you for playing it properly, you know, hearing it through enough to talk about. Thank you. It’s one thing for me to be proud of it. It’s another thing for people to respond to it and it feels great. Thank you.

How have you been managing to deal with everything going on this year? Just before we spoke you mentioned that you played played a gig, but I assume that must have been something quite different?

It is a lot different, it’s almost unrelated. It’s more of a studio session than a gig really, but a live studio session. So it definitely challenges the senses in a much different way. I do miss playing live. But it’s good, the kids are good. All ages and staying safe. Keeping masked and distant.

Your last album was out in 2018, so what was it that made you feel it was time to try your hand at an instrumental album this time around?

For one, it was finally done. It felt good, because I’d been working at it and composing it for a long time. And it was done, it was ready and that’s what I do; I release music. That’s just second nature to me. That’s how I find my creative outlet, music. So it was a record I’d always wanted to make and well before the pandemic and quarantine hit, this record was on the books and completed and ready to come out.

Obviously it was one you’d been working on for a while, but had you planned to do a more traditional album ahead of time?

No, this was the record… I had done an alternate version of this record, it was fully produced. When I say fully produced I should, that’s mis-stated because it’s fully produced. But it was, it was a more weighted production. There was, it was a lot of instruments, it was built up in a symphonic manner. And I stripped all that back.

Will you look releasing the fully-formed version at some point, or are you happy with the record the way it is now?

This will be the version, however we’ve got a couple of B-sides from the sessions we did at Capitol Studios.

You’ve cited a lot of blues musicians and guitarists as influences, so I would assume you would’ve listened to a lot of instrumental records growing up, or even today. Are there any specific artists or albums that come to mind when you think of instrumental music?

Yeah, there’s great instrumental albums, there’s great instrumentalists, and then there are people who always keep instrumentals as a staple in their set. And those are kind of the three lanes.

There’s Narciso Yepes, Enrique Segovia, Manolo Sanlúcar, Papadosio. There’s that genre and tradition; classical flamenco. Then there’s the American tradition, which is Michael Hedges, John Fahey, Leo Kottke.

And then there’s musicians who were brave enough to actually do instrumentals regardless of what was going on in music trends at the time. Like Taj Mahal has always had instrumentals in his sets, which have always been super powerful to me.

And one of the most influential slide guitar instrumentals is also one of the most influential pieces of blues music, historically speaking. Which was “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground”, [by] Blind Willie Johnson. So I’ve always gravitated towards instrumentals, from classical music to just stripped down picking style guitar.

When you decided you were doing an instrumental record, were there any specific records you looked towards as an idea of where you wanted it to go, or were you more inclined to let the music take you where it needed to?

There’s no reference point for this record. I mean, this record is just me. It’s how I play, it’s who I am, it’s what I’ve lived and it’s a sound I’ve been reaching for a long time. So as much as I am influenced by, even though the instrumentals of Taj Majal, Blind Willie Johnson and instrumentalists like Leo Kottke, John Fahey.

This record, as much as it is connected to those people, it also has nothing to do with any of them because it’s just so unorthodox I think, as far as making a record like this. I hope, it’s unique to me. Maybe it’s out there, I don’t know. It’s also connected to Hawaiian roots as well.

Well you’re right, listening to it, it feels very much you. There’s no real reference point that you can find in it, and in that way, it is indeed rather unique.

What I’m aiming to do is not say I’m unique [laughs]. I’m working really hard at not being that guy. It’s just, I just hopefully made a very personal statement. or at the very least. a statement that’s very personal to me, on an instrument that I’ve spent my entire life with.

When did you first get exposed to the pedal steel guitar? I assume that would have been from quite a young age?

Yeah, it was quite young. I’m sitting in my family’s music store of 62 years. And as you can see, there’s no reason to not play an instrument when you grow up in a shop like this.

So the sound that struck me the deepest and the youngest, was the sound of the slide guitar. I just felt a direct connection with that and to me it’s connected to the sound of the human voice in a way that other instruments aren’t, and it spoke to me early on.

As someone who has predominantly made music with other artists, or music that features vocals at the forefront, was it somewhat daunting to sit back and let the music speak for itself solely for a change? Or was it more of a natural thing in that it was something you’d wanted to do?

It was both, it was daunting and it’s very stark. And the record is, it doesn’t matter what I think it is, but stepping out in this day and age with nothing but a lap steel guitar is… You know, there’s safety in numbers sometimes but that doesn’t mean it’s the best direction, creatively.

So you know, there was safety with strings and bass and drums and keyboards and, and percussion and all of it. But if you find yourself being safe as an artist… This record needed to speak in a different way, so I was glad, because I almost turned in the fully produced record, so I’m glad before that happened and was out.

“I just hopefully made a very personal statement. or at the very least. a statement that’s very personal to me.”

Sometimes it’s hard to do what you’re doing and hear what you’re doing at the same time. It’s a strange phenomenon because there’s a certain amount of objectivity we have to have right, to be a writer or to be an artist. But there’s also a certain kind of stream of consciousness that also has to take hold for it to be outside yourself.

And so whether you’re writing an article or I’m trying to write a song, we’re trying to bring something that can… We’re trying to pull from outside of just our own kind of habits. I don’t want my music to be out of habit and I don’t want it to sound like it, because it doesn’t feel like it.

There are a lot of artists who feel that the second they fall into old habits, they recognise a need to do something different for their own sanity, effectively.

Yeah, and you don’t want to do different just for different’s sake, do you? Because then, then it’s almost the same as doing the same thing, just dressed up in different clothes. So I think it’s really important to just go against the grain and just maintain a certain sense of non-conformism and unconventionality. And I think that is an important part, and it’s easy to forget when either you write in a certain style or you can write in a certain style that might garner a certain amount of attention.

To me, this album feels like it can cross listening boundaries in a way. Some fans of music in general can sit back and listen to it for what it is, while fans of your own music or lap steel guitar in general are able to experience it on a totally different level. Was that something you had in mind, or was it a nice addition to the end product?

I just keep coming back to how all my life I’ve been mystified by the instrument. The lap steel guitar really, it’s like a great relationship where you keep learning new things about your partner, right. And I liken that to an instrument because it’s always informing me in different ways. Ideally, you hope to make a contribution, right?

“I think it’s really important to just go against the grain and just maintain a certain sense of non-conformism and unconventionality.”

Who’s the poet who said, “I’m not here to be a spectator”? [Ed. Note: Some thinking occurs before the name Mary Oliver comes to mind.] She’s great, genius. So yeah, you know, it’s always great to half-quote genius isn’t it? Makes you look real smart.

Of course, I do it all the time in my articles. But looking at the music, in the lead-up to the record, you’ve released singles such as “Inland Empire” and “London”, and I wonder about the approach that you’ve taken to them when you were recording. You mentioned it was something you’ve worked on a lot, but the end result feels so free and almost jam-like, but still fully-formed and accomplished.

I love that, that’s what I hoped… I wanted to have just enough structure to where someone will know that there has been a good amount of time spent on conducting and composing, but also a certain sense of improvisation as well.

It’s clear that everything was done in just one take, but obviously there would’ve been a lot more work putting into perfecting it over time.

There was, and numerous takes of different movements and then settling into playing the whole thing for two days straight, just playing it down front to back, front to back, front to back, and just finding what was going to bring the best out in the process.

Meanwhile Sheldon Gomberg, an incredible producer, engineer… It was nice to not have to think about the sonics at all knowing that he would handle all of that and just being able to walk in and play. He had a couple of mics in the sweet spots and the right positions, the right microphones. An amp in the other room, just for that low end compression, and I’d just walk in and we’d go.

All of the tracks named for different locations, so were they composed with the locations in mind or were they serving as a tribute to each of them?

They are serving to represent for the most part where the songs were written.

Right, so do you have a strong connection to each of these locations?

I do. But it’s important for me to say that, I have some strong connections, having been on the road for the better part of 30 years. I have some deep roots in a lot of places, for so many different reasons. That’s been one of the best parts of getting to consistently tour.

The record itself feels quite ‘global’ in the sense that you’ve got titled named after locations around the world, yet it’s an album that comes out during a year when people have felt so isolated. It feels lonesome in the sense it’s yourself playing it solo, but it also feels somewhat hopeful and even relatable.

I love that, because I had Donna from my publishing company, Reservoir, called me. She said, “Ben I want you to know that I’m playing your record and I’ve been travelling. I listened and I can’t go anywhere right now–I love to travel but I’ve been travelling by way of your music and the places. I’ve been moving with you title to title.”

And I thought that, for me, someone who hopes that it reaches people and that people take it in for what I feel it is… What you’re saying is, that hits the mark for me. I guess my ultimate hope for the record would be that people can hear reflections of the place in the melodies. That you can hear Harlem and you can hear Paris and feel London through my sense of melody would be… that’s a whole other conversation.

The album has taken a while to arrive, but would you look at doing another instrumental album down the line? If you did, do you feel it might take a different form or see yourself on a different instrument?

I think either something will kick open and then you know, this could be one of three. I’ve always felt my first three records, Welcome to The Cruel World, Fight for Your Mind and The Will to Live, I always felt like those were like a three part record. And they were just one after the after, ’94, ’95, ’96. And that could be the case because I am hearing music in a new way.

This record has opened some ideas and it’s provided a sonic clarity to me that didn’t exist before this record was completed. So it could be the first of however many, or I can sit around and it could take another 20 years to actually have the material.

“I am hearing music in a new way.”

At least it’s good to know there will always be more material on the way from you, because as you said, “it’s what you do”.

I’d be doing it either way but there’s a component to music that is conversational, to where the song is completed when the person receives it. And to have been able to have that dialogue and that dance, and that communication for as long as I have. Every day I grow more and more appreciative of that reality for me.

So when you say there’s more music for me to make, it’s because I get to talk to you, I get to connect with people who appreciate it. And there have been moments [of] great highs of ego and great lows of self-loathing, but it feels good to be at a way station right now as a person and as a player; musician. This record’s provided a great source of solace and comfort for me, I don’t know. It’s strange, I’ve never felt this way about a record.

You’re a live performer and there hasn’t been much of a chance of that this year, so is this an album you’d look at performing live when you can?

That is one of the first things I’m going to play when I’m able to get out.

“It’s strange, I’ve never felt this way about a record.”

I feel an album like this lends itself to smaller, more intimate venues where you can really hear the sound of friction against the strings.

I just might do it different. Once this comes to an end I might just say, “Hey listen, just have me come to the house.” Like, let’s just get a list. I’ll just come to a city and then go to ten people’s houses, man. I’ll just play people’s backyards. At this point, man, I’m just ready to play.

A buddy of mine, he was planning on proposing to his girl and he said, “Hey, you know, would you play a couple of songs? I’ll surprise her on the computer and then I’ll turn out the lights and then you start to play.” It’s like, “Sure man, you got it,” and I did it.

After the first song they applauded and I was like, “Wow”, and it hit me that I hadn’t heard applause in you know, seven, eight months. Which is as long as I’ve gone as an adult without hearing applause.

Ben Harper’s Winter Is for Lovers is out today via ANTI- Records.