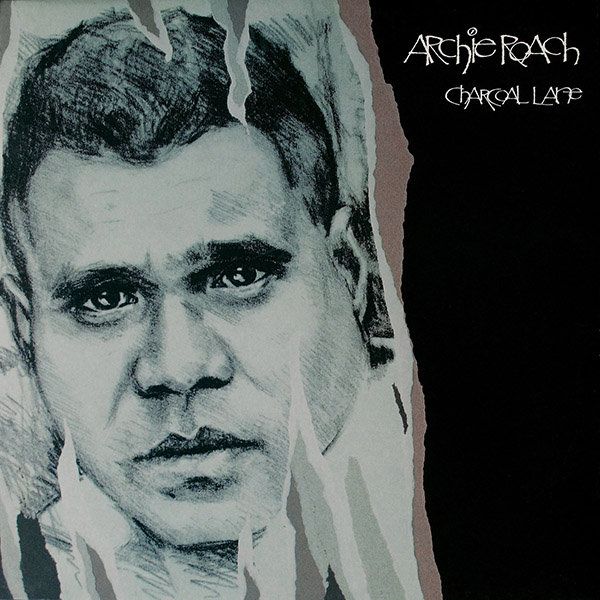

Thirty years on from the release of Archie Roach’s groundbreaking debut, 'Charcoal Lane', Jack Latimore looks back on the iconic record.

Thirty years ago, a vigilant young man with a storied life and a lasting enthusiasm for country music was presented with a classic crossroads bind. An opportunity had suddenly fallen his way; the offer to cut a record more-or-less of his own choosing, to be produced by some of the hottest names in the Australian music industry.

It didn’t take a flotilla of intuition to realise the offer was kind of a big deal, and real enticing, but Archie Roach remained ambivalent still.

The young fella and his partner, Ruby Hunter, had done some hard living, faced tricky demons, scraped through intact, and got themselves back on steady rails. Both were now working in health service roles assisting Melbourne’s Koori community and living contentedly with a house full of kids in the northern suburbs. But around a week earlier, Roach had performed a two-song, 25-minute set as a support act for Paul Kelly and the Messengers at the Melbourne Concert Hall that left the unsuspecting house gobsmacked, asking, “Who the hell was that! Where did he come from?”

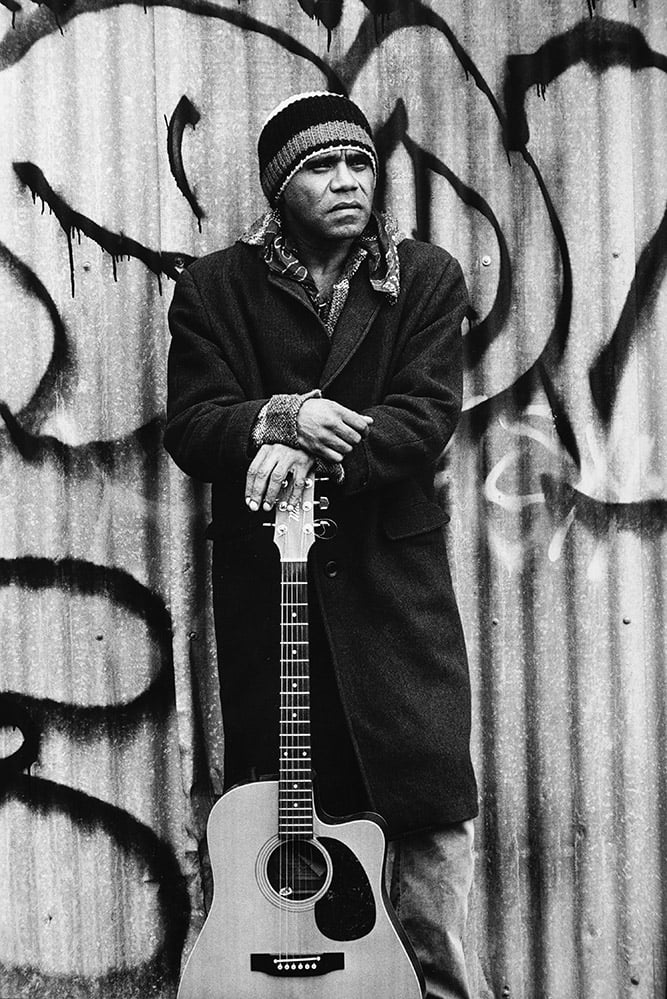

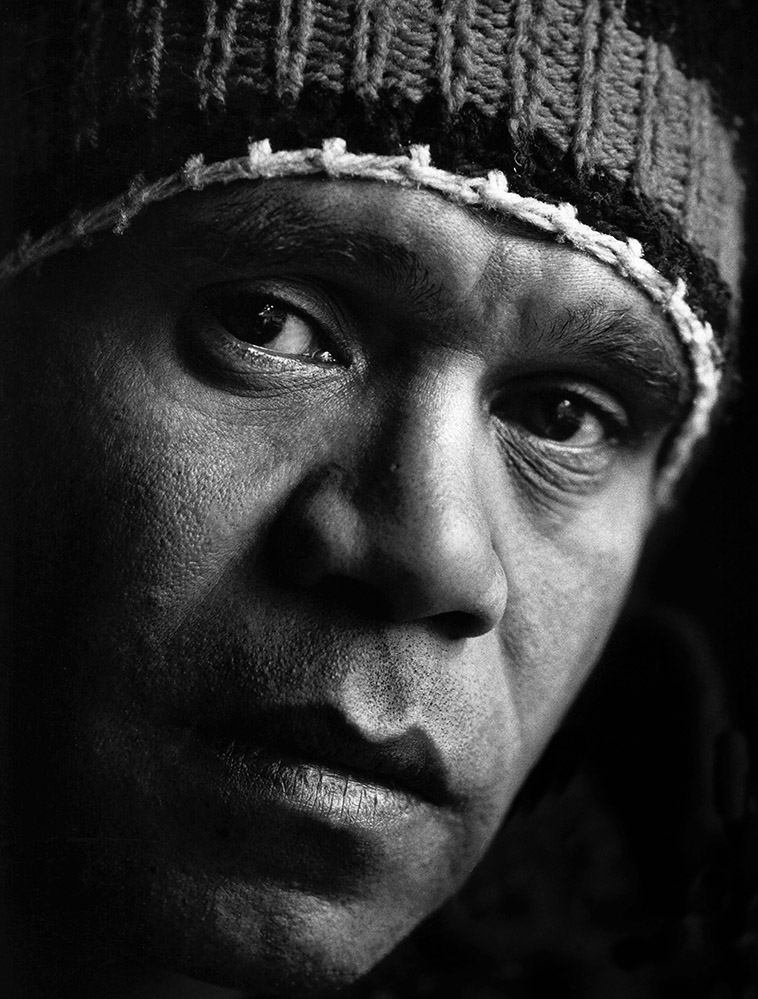

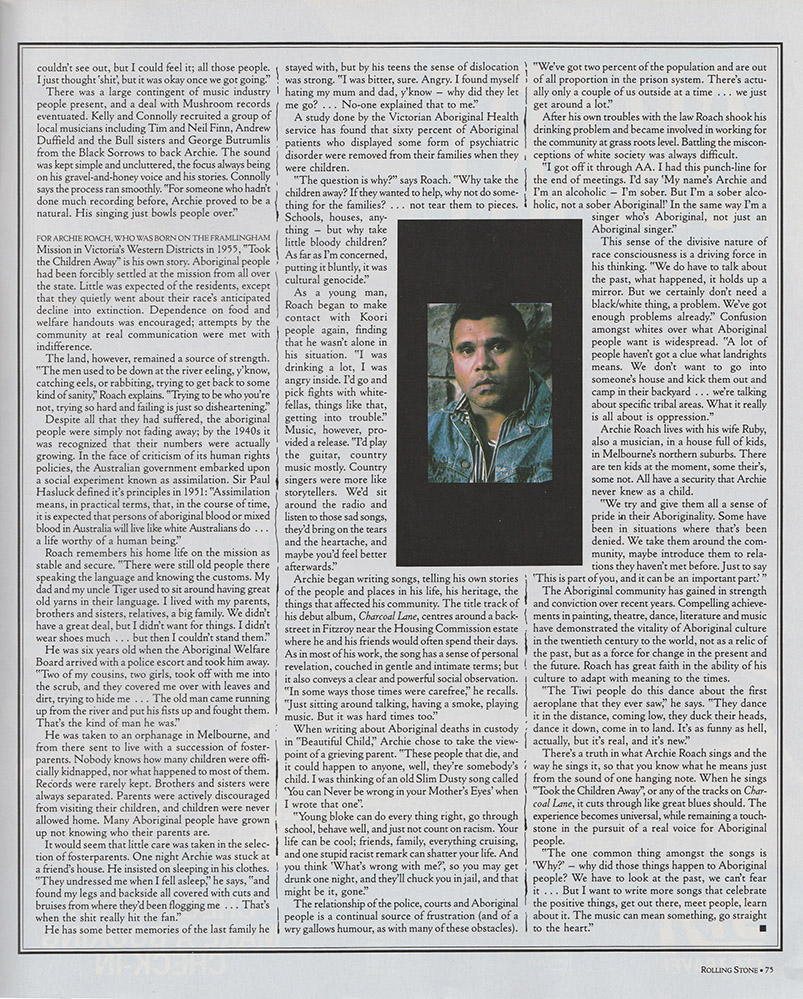

Archie Roach photographed prior to the recording of Charcoal Lane in 1989. (Photo: Bill McAuley)

Those in the know, well, they knew – the artist hadn’t come from nowhere. Not by any measure. Messengers guitarist Steve Connolly had spotted a performance by the gently-spoken Gunditjmara fella on a niche-audience television program called Blackchat, a month prior to the concert hall gig.

There were others too, milling in the circles of Melbourne’s thriving music scene, who knew the singer Roach from an interview several years before on 3CR, the city’s radical community radio station.

The grand pantheon of popular entertainers contains numerous legends of awe-striking moments of arrival: there’s Hank Williams playing “Lovesick Blues” on stage at the Ryman Auditorium for the Grand Ole Opry radio show in 1949; there’s Patsy Cline singing “Walking After Midnight“ on the Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts television show in 1957. Roach singing “Took the Children Away” to a full house on the bank of Melbourne’s muddied river Yarra in 1989 is among them.

In his 2019 memoir, Tell Me Why, Roach recalled the performance. Upon opening with the track, “Beautiful Child”, Roach went into what he describes elsewhere in the book as a “dissociative state”.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

He sang the song about Lloyd James Boney, a 28-year-old Aboriginal man from Brewarrina in northwest New South Wales who was found hanging by a football sock in a local police cell in early August 1987 – just 90 minutes after being violently arrested by three police officers for a breach of bail. Roach was met with silence when he finished the song: “‘Maybe you’ll like this one,’ I said, before launching straight into ‘Took the Children Away’.”

More silence followed the end of the second song too. Then came a trickle of applause, gathering quickly into a surge of “real, roaring approval”.

Archie Roach photographed prior to the recording of Charcoal Lane in 1989. (Photo: Bill McAuley)

Watching from the wings was the headlining act that evening. In his 2010 memoir, How to Make Gravy, Paul Kelly recalled that all the hairs in his body stood up as he watched Roach’s brief set, and that he could feel the same thing happening out in the hall.

Singer Linda Bull was looking on from the wings, too. Recalling that moment from 30 years ago, Bull remembers the crowd’s stunned reaction.

“I’ll never forget that. The whole hall was quiet, you could hear a pin drop,” she says. “The voice, and his whole demeanour – there was nothing like it. I’d never heard or seen it before, the effect that his voice had on such a massive group of people.

“And as he was walking off I just remember the applause. It was incredible.”

The people behind the record label Kelly was signed to were similarly impressed. They wondered whether Roach might be interested in recording an album.

“I didn’t have much interest in doing an album, though,” Roach writes in his memoir. “It felt as though I’d only recently found a life that worked for me and Ruby and the boys, and I didn’t want to upend that apple cart with any complications.”

So, at the crossroads, Roach initially decided to decline the offer and duly informed Ruby of the direction he would be taking. But Ruby was having none of that: “It’s not all about you, Archie Roach,” she reminded him. “How many blackfellas you reckon get to record an album?”

Ruby recognised from the get-go that Roach could set a shining example for other blackfellas, that the album offer was also an opportunity to keep giving back to their Koori community, and more mobs beyond.

So Kelly and Connolly began a series of visits to Roach’s home in Reservoir. Hunkered around the kitchen table, they enjoyed refreshments of tea and sandwiches between a number of jam sessions with Roach, Ruby, and their young boys.

The songs of country greats were played: Hank Williams, George Jones, Willie Nelson, and Johnny Cash got a good run. So too did Merle Haggard and Charlie Pride. Kelly recalls the trio also tried on some great blues and soul from artists like Ted Hawkins and Sam Cooke.

Suitably impressed with one another’s repertoires and having established some mutual trust, the sessions got around to Roach’s songs. There was some figuring out to do as to what might be carried into a studio. Nine songs were identified, plus one Ruby had written called, “Down City Streets”.

“Archie’s songs were like a reportage of a hitherto hidden world – stories from the shadows, from the margins, from the dispossessed,” Kelly later wrote in his memoirs.

Several months on, the three artists met in Cotton Mill studio in Carlton to record what would be titled, Charcoal Lane.

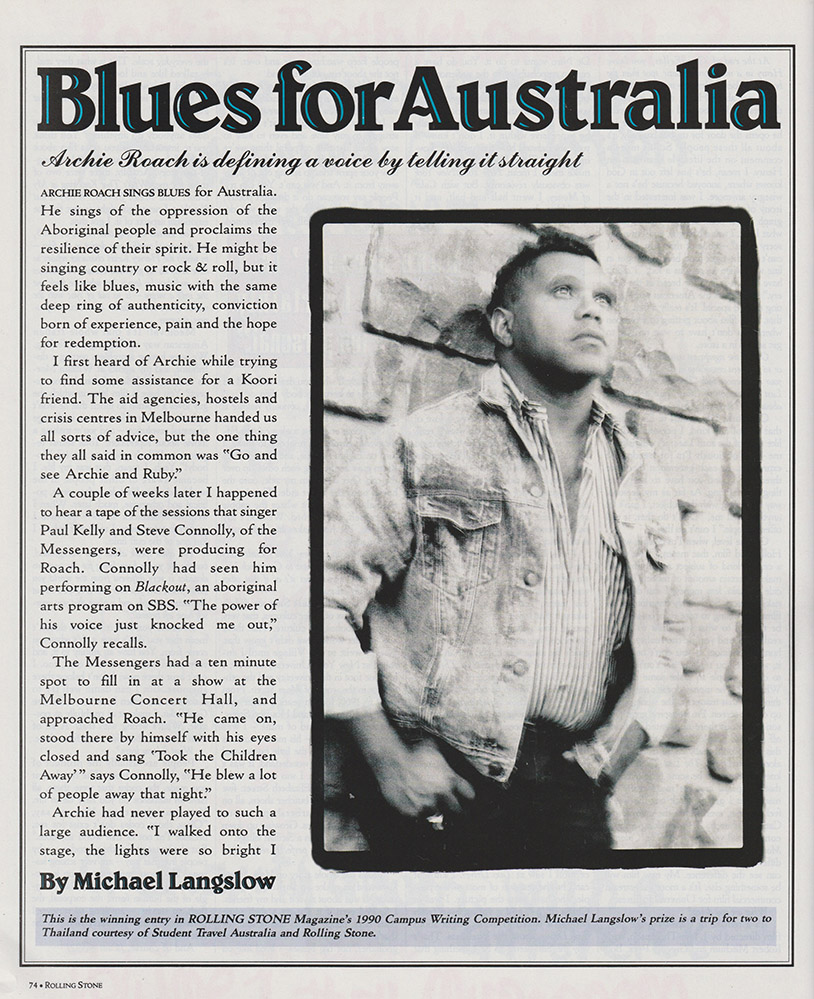

Around the time of the album’s release in 1990, Rolling Stone Australia magazine held a writing competition for university students that boasted publication and a trip to Thailand for the winner. It’s difficult to know now how many submissions were mailed in, but among them was an article about Charcoal Lane composed by an architecture student at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology.

Michael Langslow’s writing took the prize and still holds up well today. Langslow wrote about Charcoal Lane’s honesty (a term these days twisted into the twin-barrel signifier, “truth-telling”) and its “deep ring of authenticity”. The album felt like the blues, he said, regardless of it being a little bit country, a little bit rock‘n’roll.

He’d heard word on the street about Archie and Ruby, heard a tape of the kitchen table jam sessions too. It’s clear, on a first reading of the article, that Langslow is part of the city’s music scene, an insider with a tip. This is confirmed thirty years later, when Langslow reveals Connolly provided him with the tapes.

But it’s also clear from the article, that it’s white writer gets the issues impacting Blak bodies and communities and is just as aware of the Cause – the self-determined drive to uplift and empower Aboriginal peoples – as he is familiar with the music scene.

Michael Langslow’s 1990 article on Archie Roach for Rolling Stone.

Michael Langslow’s 1990 article on Archie Roach for Rolling Stone.

Contacted by Rolling Stone Australia on the 30th anniversary of the album’s release, Langslow explains that this awareness stemmed from a series of paintings his grandfather, Sid, had done on black deaths in custody in the Eighties, particularly around the case of John Pat in Western Australia.

“They were really powerful paintings. Very confronting. So, I had certainly been aware of the politics from that time on,” says Langslow.

Langslow’s grandfather, Sidney Nolan, is best known for his heavily stylised, iconic ‘Kelly’ paintings, but in the late Eighties, as an elderly man, the internationally-renowned artist produced a series of experimental spray paintings. Many of the works in the series are untitled, sprayed on unprimed canvas. The images consist of simple, blurred busts of Blackfellas, many deceased with a cord about the neck, or their wounded bodies entangled in bars or wire. They are images at once brutally tangible and ethereal, the subject matter captured mid-dispersal.

John Pat was a 16-year-old Aboriginal boy when he died in police custody in Roebourne, a hub town in the Pilbara region of Western Australia in 1983. His death came via multiple massive blows to the head – an injustice that sparked calls for an investigation into the deaths of many more Aboriginal people in custody. More questionable Black deaths in detention over the next four years, including the circumstances of the death in custody of Lloyd Boney, eventually led to the announcement in mid-1987 of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.

While the Royal Commission didn’t deliver its landmark final report until 1991, a year after the release of Charcoal Lane, the album was imbued with the raw account of the impacts of systemic racism on Blak lives: a parallel to Nolan’s 1987 spray paintings series. More prescient was the matter of stolen children. It is impossible to deny the contribution of Charcoal Lane, and specifically “Took the Children Away”, to the commencement of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their families that followed five years after the album’s release.

“I think Archie was one of the first people to break open the whole Stolen Generation story and the rest of us knew so little about it up until then,” recalls Langslow. “The term ‘Stolen Generations’ hadn’t come into the language yet.”

nother two years after that, the inquiry’s Bringing Them Home report was tabled and the devastating, transgenerational impacts of systemic racism on Blak lives was made public again, arguably in even greater relief. One key recommendation in the final report called for a national apology. A concept that bristled the staunchly conservative Prime Minister at the time into rebuking the report for what he termed as its “Black armband view of history”. John Howard’s refusal to apologise on behalf of the Commonwealth for its past policies that led to so many deeply traumatised lives and communities, so many abuses and loss of life would incite the ‘history wars’ that continue to flare like fierce spot fires to this day.

This is the significance of Charcoal Lane on the contested field of Australia’s national identity. The album is critical in both senses of that word. It provided a light – with stories from the shadows, from the margins, from the dispossessed – and held the morally corrupt to account, as all true reportage should.

When contacted for this article, Kelly says he and Connolly – like Ruby – had a keen sense the record was going to be important from the get-go.

“I was struck by the fact that every song was a love song – to clan, Country, family – and at the same time intensely political,” says Kelly. “Not many writers can do that. Steve and I felt that our job as producers was simply to stay out of the way of the songs and not clutter them with too much production. We felt we had been entrusted with a solemn duty.”

Roach’s last ever national tour, Tell Me Why, was postponed in March when the coronavirus pandemic escalated in Australia with outbreaks across the nation leading to the states and territories locking down their borders. Where one borderline shuts another frontier opens, and Archie Roach launched a YouTube series on Charcoal Lane to celebrate the 30th anniversary of his multi-award winning 1990 debut album, looking at the songs and stories behind the record from his kitchen table.

Archie Roach is also set to be inducted into the ARIA Hall of Fame later this month.