Needles and Plastic: Flying Nun Records, 1981–1988 is far larger and more lavish than any New Zealand rock history attempted to date, no less one dedicated to Flying Nun alone. Arguably the country’s greatest cultural export, the Christchurch record label came to national and international attention in short order upon first releasing The Clean single “Tally Ho” in 1981.

Rolling Stone was one of the scene’s first champions; Dunedin record store owner Roy Colbert reviewed live shows of The Clean in the magazine before the band had released anything. Flying Nun label founder Roger Shepherd’s DIY approach to recording and releasing as much music as possible was enthusiastically supported by the bands, many of whom had no contracts.

The collaborative approach led to an avalanche of output, which has since garnered an underground cult following. Released earlier this month, by a Canadian no less, Needles and Plastic has already earned praise for its exhaustive cataloguing of the early years of Flying Nun—including from Jack White, whose publishing house Third Man Records has picked up the American distribution rights. While some bands have received more attention than others, Needles and Plastic bucks the trend with its even-handed, chronological structure, documenting every release between the label’s inception in 1981 and 1988.

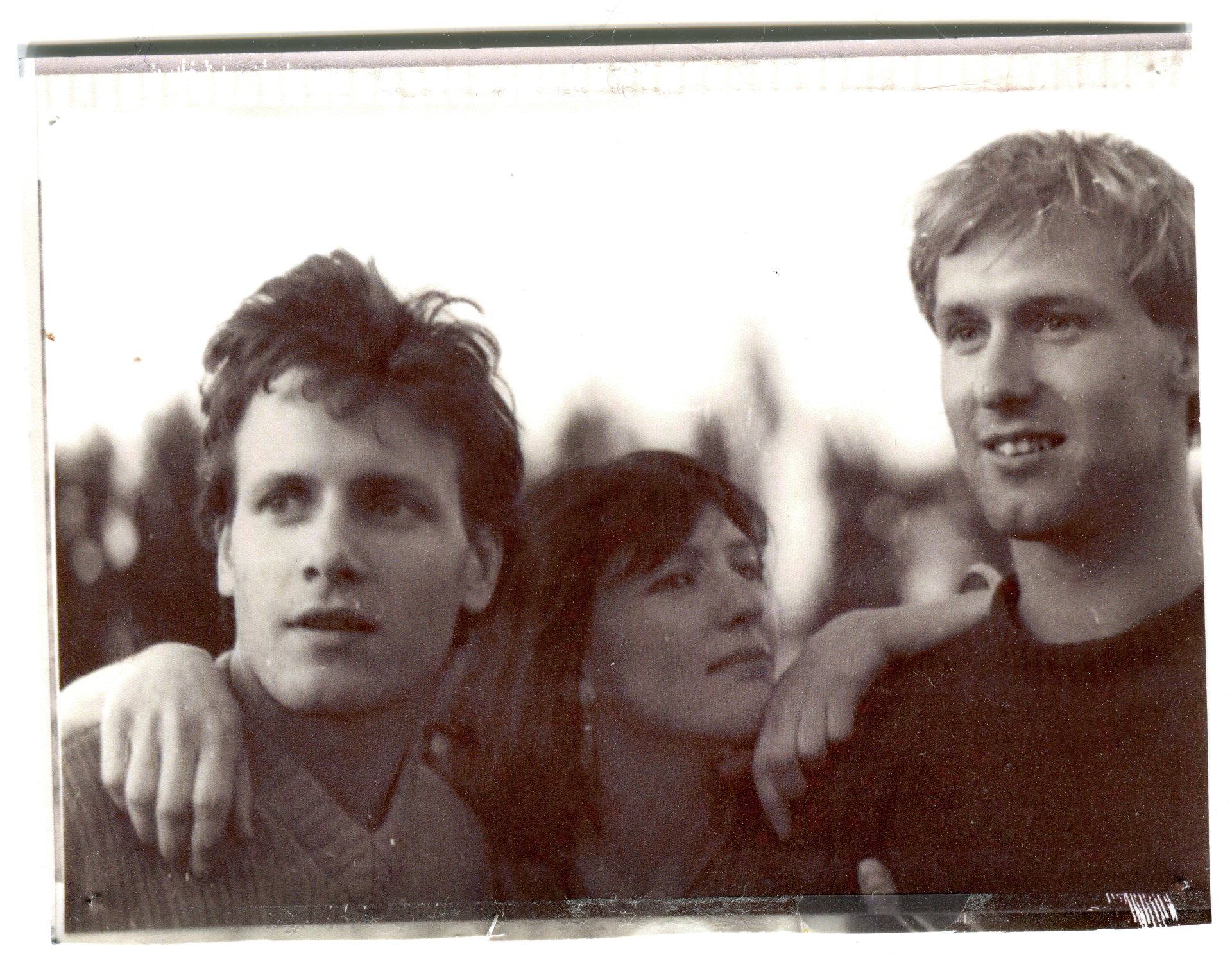

They Were Expendable: Nick Strong, Jay Clarkson and Dave Toland. Photograph: Kaye Woodward

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

At the launch, Canadian author Matthew Goody explained that it was an attempt to be democratic. “I tried not to inject my own personal…”

The Pin Group’s Roy Montgomery interrupted him. “You should’ve.”

Mainly Spaniards on the Basilica steps. From left, David Swift, Nick Strong, Mike Jefferis and Richard James. Photograph: Kaye Woodward

The Christchurch leg of the book launch was held at Lyttelton Coffee Company on a warm Wednesday evening in the late spring. Roy Montgomery and The Dead C’s Bruce Russell were on the panel, but the quality of indie rock calibre in the audience was what made the gathering legendary. Hamish Kilgour of The Clean sat up front, dark curls spilling out from underneath his pageboy cap.

Alec Bathgate of The Enemy, Toy Love and Tall Dwarfs was there, too. Stephen Cogle of The Terminals asked whether label founder Roger Shepherd bothered to attend the Wellington launch; Rachael King of The 3Ds and The Cakekitchen provided a much-needed feminine perspective of the era upon request. Dave Imlay of Into the Void and No Exit leaned against the wall with his beer. Sharon Sab of The Outsiders and “the Lukes” of The Opawa 45s posted up in the back. Ben Woods watched from behind the bar, taking it all in.

Yet the scene was far from complete.

A bit further down London Street sits a concrete building adorned with the faded signage of Lyttelton Service Station visible through a thin white paint job. The panels covering the windows are painted in shades of gray and adorned with white wooden frames, each one featuring posters bearing the same name as the last: MEDaL. The upper row is a pulp fiction pastiche of pop culture: Evil Knievel, Donald Trump, a car crash, a dalek, a skateboarding dog wearing a tinfoil hat, a Rockette on a rocket. The bottom row of black A4 posters announce the release of their second album Sequela on November 11. Only the colour of the band’s name changes, alternating blue and pink.

Saturday night after the book launch, the silver garage door rolls open slow, heavy with tension, as if about to reveal an arch nemesis. Inside, the three Christchurch musicians now known as MEDaL sit on worn couches, drinking cheap green lager. The band consists of Flying Nun alumni who are still active, albeit in bands currently receiving little attention outside the South Island. Rather than attend the launch, the band was parked up at a bar across the street instead.

“The last thing I need is to go listen to people I know talk about themselves.” Dave Mulcahy’s voice was flat. Three of his records with The Jean Paul Sartre Experience are featured in Needles and Plastic: their titular 1986 debut EP, the 1987 single “I Like Rain”, and the album Love Songs in the same year.

The Jean Paul Sartre Experience.

Mark Whyte still drums for The Christchurch band Into the Void, whose 1993 heavy metal meets sludge album on Flying Nun was an outlier amongst the jangle pop. The band entered another era of local fame as the longest-running deadbeats of the Christchurch rock music scene in 2014 thanks to Margaret Gordon’s documentary on the band, which she described as “part character study, part art piece, part comedy and part rock’n’roll narrative”.

“We are probably so bad Flying Nun don’t like mentioning it.” Whyte cackled with laughter. “We won’t be in that fucking book.”

Into the Void. More coming soon, the Flying Nun page on the band promises. We’re still waiting…

Mulcahy was pragmatic. “But it’s quite chronological, isn’t it? Didn’t he do all that releases for that period of time? I don’t think he edited out anyone.”

John Billows smiled wry. “You just like to think you were the bad guys.”

John Billows didn’t make it into the book, either. Although one of the original members of The Renderers, the band formed in late 1988, which is beyond what the book covers.

The Renderers at the Christchurch Media Club. Left to right: John Billows, Michael Daley, Maryrose Crook, Brian Crook.

MEDaL formed in 2019 out of the remnants of the Sexy Animals after the passing of lead singer Mark Banfield.

“I was at the Dux de Lux with Dave Imlay watching the Sexy Animals,” Whyte remembers. “And I said to Dave, ‘These guys need Sly and Robbie.’ Meaning him and me.” He laughs. “Then I bailed, and then I don’t know, Dave must have mentioned something to Mulc…”

“That’s not how I remember it,” Mulcahy interrupts. “I remember seeing Into the Void playing and thinking, ‘I’m gonna nick the rhythm section.’”

Although all born in Christchurch, the musicians of MEDaL travelled different paths before coming together as a band. Mark Whyte has remained in Christchurch with Into the Void since 1986. John Billows moved to Australia with his partner Joanne Billesdon—of Christchurch 80s all-girl bands SNORT and The Stepford Five—and then onto England before returning to Christchurch in 2016. Dave Mulcahy and The Jean Paul Sartre Experience followed Flying Nun to Auckland 1988 and remained there for the next 10 years.

“We knew that if we were going to try to get support from [Flying Nun] we had to be based there and we had to be in their face all the time,” Mulcahy said. “Otherwise we would have just become more of a second tier band. You had to be in there and fucking drinking with them, and just going in there every day: ‘What’s happening? What’s happening?’ Not that it made any difference, but…” Mulcahy paused. “Into the Void were more clever like that, were they?”

“Aloof arty types.” John Billows smiled. “Leveraging that.”

If anyone ever wanted Into the Void to diverge their attention from their everyday lives in Christchurch, they had to pay for it.

“Flying Nun used to fly us places to play,” Whyte said. “It was great. They flew us up to play in Auckland. Chris Knox said, ‘How the fuck did YOU get here?’”

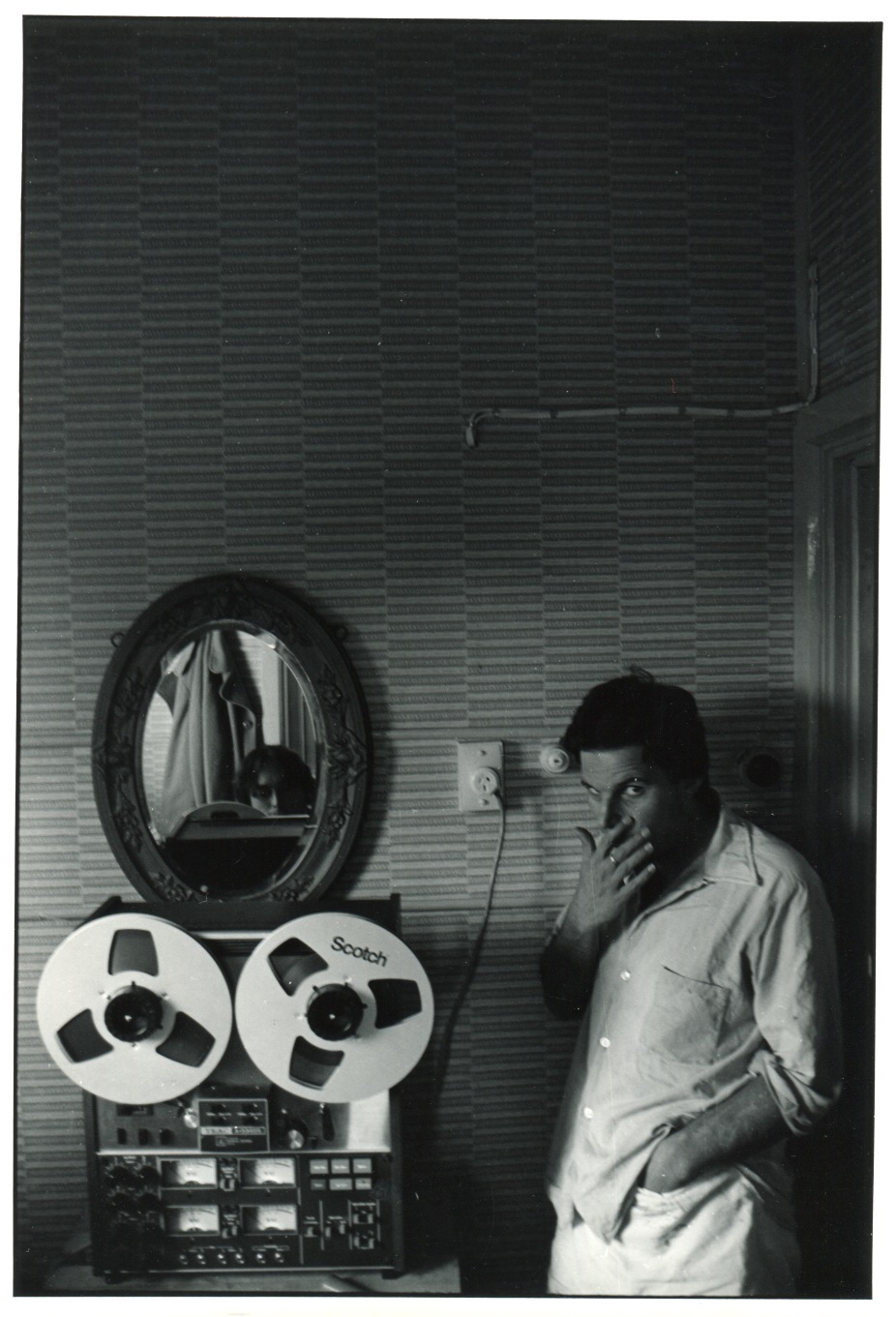

Chris Knox and Doug Hood (in the mirror) with Knox’s TEAC four-track. Photograph: Alec Bathgate

Christchurch bands are used to being overlooked. Despite the label’s Christchurch origins, the label “the Dunedin Sound” has become irrevocably tied to the bands, and the South Island’s largest city was all but wiped out of the narrative. The Chicago Tribune called Dunedin the “rock capital of the world” in 1992; the London-based newspaper The Guardian claimed that Dunedin had “arguably the greatest per-capita concentration of talented musicians in the history of pop” in 2014.

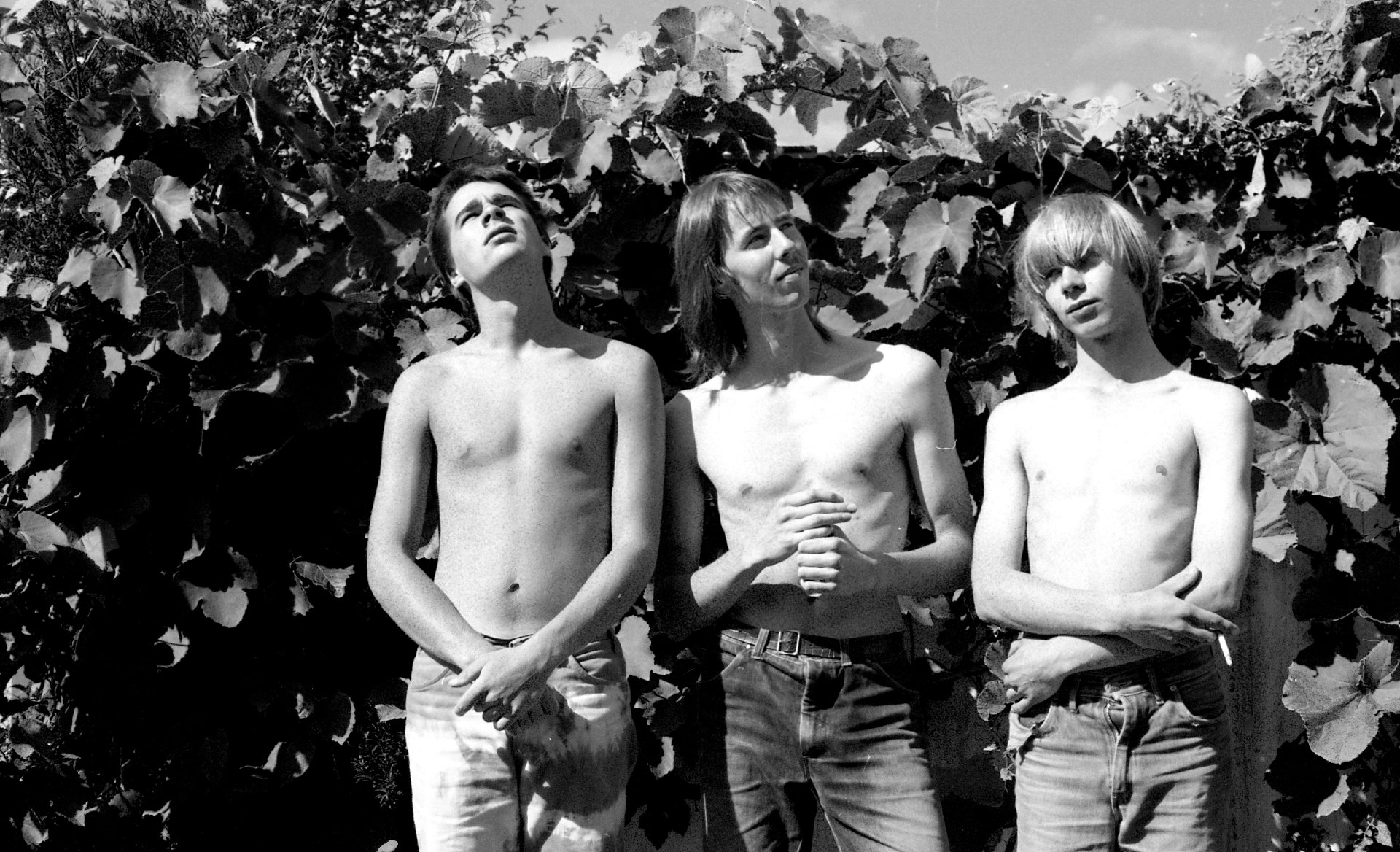

The Stones shirtless in Dunedin sometime in early 1982, an image used for the band’s cover of the Dunedin Double. From left, Jeff Batts, Graeme Anderson and Wayne Elsey. Photograph: Paul Kean/Kaye Woodward

“We’re lucky we got any coverage at the time, with the exception of Roy Colbert,” Roy Montgomery said.

“New Zealand doesn’t have as much coverage as it used to,” Bruce Russell conceded.

At the launch, Bruce Russell called the book’s final date of 1988 “highly appropriate” because it “terminates in the aftermath of the tsunami”. The “tsunami” refers to two well-known events in New Zealand rock history: the nation’s only record plant in Wellington closed—rumours are it was thrown into the Cook Strait—and Flying Nun subsequently relocated to Auckland to be closer to distribution networks that included Australia, where records were still made.

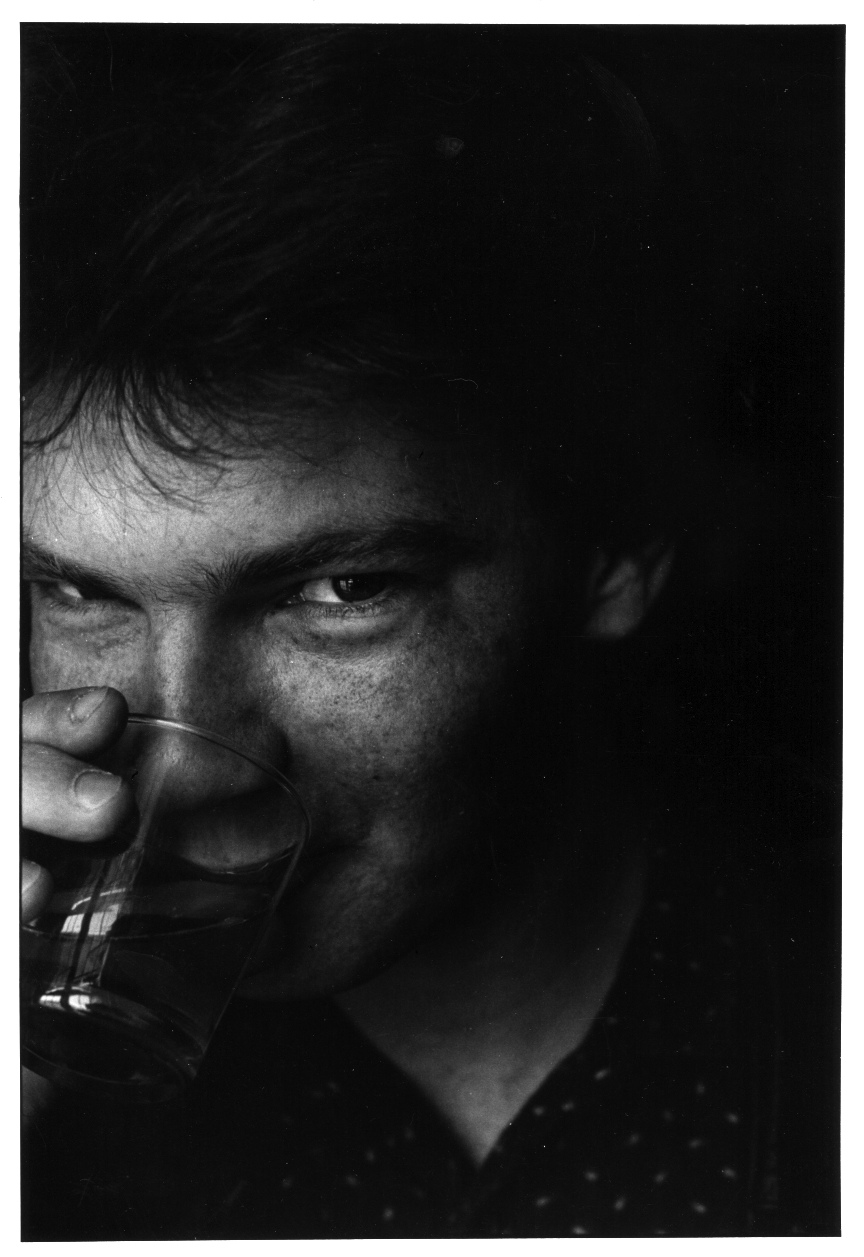

Roger Shepherd, shot by Alec Bathgate for Rip It Up, 1983.

When Roger Shepherd departed for Auckland, it delivered another blow to the South Island, adding to the suffering of its slow loss of economic power to the North Island over the last 120 years. Retrospectively, the 1980s are now seen as the label’s golden years, even by a Canadian author who arguably had no hand in old island rivalries. Success stories are less popular in New Zealand, where small poppies are more prolific than the proverbial American bootstraps.

The Chills, 1985, from left, Martin Phillipps, Alan Haig, Terry Moore and Peter Allison. Photograph: Lesley Maclean.

In the years since, much like Dunedin, the 1980s have been fetishized to the point of exhaustion. Shayne Carter of Straitjacket Fits complained in Sunday Magazine in 2011, “It’s become almost mandatory to have these three phrases in the same sentence—’Flying Nun Records’, ‘Dunedin Sound’, ‘1980s’”. Many musicians felt that Flying Nun’s decision to relocate crippled the local music industry. But Whyte disagrees with the ‘tsunami’ narrative signalling a radical change in the Christchurch rock music scene.

“We couldn’t give a fuck if Flying Nun ditched [the South Island],” Whyte said. “We weren’t in a band to be humongously famous and be cruising the world doing that.” His pace quickens; his voice lifts. “We weren’t doing it for that! We were doing it for us!”

On the one hand, Goody deserves credit for challenging the predominant narrative of Dunedin as the centre of alternative New Zealand rock culture.

“I wanted to publish internationally and bring the attention back to Christchurch,” Goody preached to the crowd at the launch. “People always say, ‘Dunedin, Dunedin, Dunedin’; to me, it has always been associated with Christchurch.”

At the same time, by focussing on the 1980s to the exclusion of all else, the fact that the musicians are still active—and the plethora of bands that form, dissolve and reassemble into new combinations, including the meditative kraut pulsing of MEDaL interspersed with explosions of joyous, fast rock—may continue to go unnoticed.

“Flying Nun aren’t very interested in us anymore as a label,” Mulcahy admitted. He thumped Needles and Plastic, which sat beside him. “When this era was happening, Roger would try and release everything that was of interest to him. And that was quite different. Whereas now, it’s much more of a proper thing, you know? Where they try to operate as a company and be economic.”

There is no album release show planned for MEDaL’s second album, let alone a tour. Everyday life takes precedence. The band likes Lyttelton.

“We often play at Loons or the [Lyttelton] Coffee Company and just wheel our gear down there,” Billows said.

“Wheel it down the road!” Whyte erupts in laughter. “So lazy!”

“So we need to play Christchurch,” Billows conceded.

“On tour?” Mulcahy is incredulous. “Through the tunnel?”

There are vague plans for a tour beyond the tunnel—to not only Christchurch but Dunedin and the North Island, too—in the summer months ahead. But for now, all that is on the horizon for MEDaL is sound and camaraderie. The sun has disappeared over the rim of the crater. I take my leave; the hours are dwindling and the band has yet to plug in. The garage door rattles shut and the band roars to life.

The early years of Flying Nun remain a special period in the hearts of many because the label was born out of a genuine love of one’s surroundings and the desire to preserve it. Before the record label left Christchurch, it was young and optimistic and had no lofty ambitions: it simply existed. That spirit still lives on the South Island whether heard or not—but a tree that falls in the woods is harder to hear from a distance.

Needles and Plastic provides a much-needed service in that sense, collating and amplifying years of anecdotes, photographs, album covers and posters into a beautiful and heartfelt tribute. Honouring the past is a noble cause so long as it is put in its proper place: enhancing one’s experience of the present rather than at its expense.