Giulia McGauran*

Tash Sultana is a born superstar, unapologetically shaping their own destiny, but all growth comes with some discomfort. Poppy Reid chats to the world-beating musician.

When Tash Sultana checks into a hotel on tour and is filling out the necessary details, they tick ‘Dr’ or ‘Professor’. They enjoy it when the staff address them like this, but they don’t do it for cheap thrills.

“I have always felt fluid,” Sultana says of their gender. “I find it really strange that we address people by Mr, Miss, and Mrs. Why does it matter about a female marital status, but not a man’s? What’s the fucking point? I don’t get it.”

It’s the day after Sultana’s sold-out show at Sydney’s Hordern Pavilion. The crowd would never have known that after five weeks of stamina-building rehearsals – which ran for six hours straight – Sultana developed laryngitis and was struggling to even speak beforehand. Management team discussions soon turned to cancellation strategies about how they might break the news to the lucky 1,000 fans who nabbed a ticket to the November show. Tash Sultana usually sells out venues three times the size and COVID-19 restrictions for limited capacity sent some rushing across borders to attend.

Dressed that night in black pants and a long, baggy black T-shirt, Tash Sultana didn’t even reveal they were sick until way past the hour mark. Their long sandy hair waterfalled down their back as they careened across the stage. They launched effortlessly into the technical multi-genre patchwork of psych-rock and lo-fi blues that make up their music catalogue. Sultana weaved between instruments as if holding back wasn’t an option, stopping at the four-channel loop pedals and jumping onto stage risers, where the guitar solos looked as behemoth as they sounded.

The instruments, freighted in from Melbourne, weighed two tonnes collectively and were placed with arduous precision at Sultana’s loop station, which they’d spent the last two years building. Four weeks before the show, Sultana had announced it would be their last as the now overused epithet “one-person-band”. 2021 would bring with it a new record and an entirely new stage performance, complete with three other touring band members from Perth who will jump onstage for half of each set. It was the end of an era.

The new issue of Rolling Stone Australia, featuring Tash Sultana on the cover. (Cover photo by Giulia Giannini McGauran (AKA GG McG) for Rolling Stone Australia)

When Tash Sultana meets me the following day at their co-manager David Ash’s place in Coogee, they enter the room with quiet efficiency. Their fiancée Jaimie takes a seat as Sultana commands the room without even trying. Wearing a black Brixton “Know Your Rights” snapback and a Hard Rock Cafe Orlando cut-off singlet with long light denim shorts and white lace ups, it takes all of 60 seconds for them to pick up the nearest guitar – their co-manager’s Capri Orange Fender Telecaster.

Moments later, when the topic arises, they launch into an anecdote about the time their dad fell backwards while bowling. Sultana throws their right arm forward, then up, impersonating him getting stuck in the finger inserts.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

It’s the tail end of a year bound by bushfires and a decade-defining pandemic for the city, and now, as we sit outside on the patio at the back of the apartment building, it has been engulfed in a heatwave. It’s the hottest ever Sydney November on record, but Sultana seems entirely unperturbed. Right now, they’re speaking about how they’ve always been gender nonconforming.

“I don’t care if people say they and them. I just don’t like being referred to as Miss or Ma’am or queen, or woman. Because I don’t feel that way, I just feel… ‘person’. That’s it,” they nod. “And when I look at other people, I look at them the same. That we all have the same capabilities.”

“I don’t care if people say they and them. I just don’t like being referred to as Miss or Ma’am or queen, or woman.”

Around five years ago, they did actually tell their fans about their gender with a Facebook status update, but quickly deleted the post. The emotional armour needed to have that discussion with your inner circle, let alone the entire world, takes time to build. “There’s just some stuff that’s unnecessary to post when it can just be personal,” they say.

They affirm their identity in many ways, from the way they dress to the way they only wear makeup when they feel like it – today is not one of those days. In 2019 they affirmed their authentic selves by changing their name officially by deed poll to Taj Hendrix Sultana; the name popped up on our Zoom call earlier in the month.

“Society is what makes people not truly themselves.” Sultana offers short, sharp hand gestures to emphasise certain words. “[…] Whether it be politics or religion, it makes people have these arguments for falling outside of that spectrum. Which is really silly because some people are born and they don’t want to wear girl’s clothes, and they don’t want to wear boy’s clothes. But sometimes they might want to, and sometimes they might not want to wear any clothes […] I just think it’s outdated and it’s dumb.”

Tash Sultana raises a logical point. More people are beginning to question whether gender norms are archaic societal constructs that need reexamining. Many are wondering why these rigid roles need to be maintained in our modern society, and have highlighted how oppressive it can be when people are narrowly confined by the conventions of the past.

In any case, physical appearance isn’t important to Tash Sultana. Granted, they treat their body like a temple, embarking on a three-hour ritual before each show: water therapy, steaming, light therapy, meditation, essential oils, drinking Chinese herbs… They’re even sipping on herbs from a reusable stainless-steel bottle as we speak. It’s more that bodies don’t signify any meaning to them outside of the physical experience on Earth.

Tash Sultana photographed for Rolling Stone Australia. (Photo by Giulia Giannini McGauran (AKA GG McG) for Rolling Stone Australia)

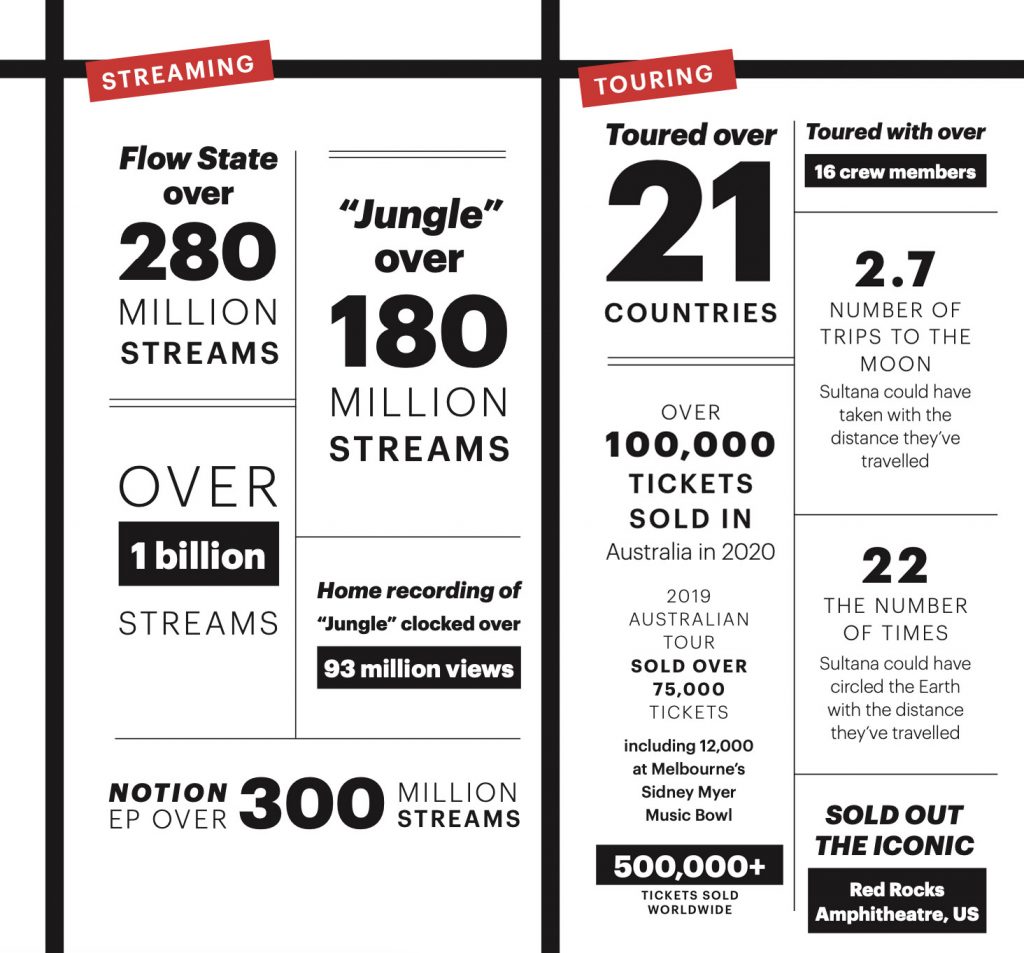

At the height of their success right now, having just passed one billion streams for their music, following sold-out dates all over the world, and on the eve of the presentation of two double Platinum plaques for 2017’s breakout single “Jungle” and the 2016-released Notion EP, Sultana confesses that they feel insecure sometimes. Even now, following a sold-out show in Sydney the night before, they ask me multiple times whether I think the fans enjoyed it. They listen intently when I recall how people were jumping up and down in their COVID-safe seats.

Given it was Sultana’s first show since February last year – the longest they had gone without playing a gig since the age of 13 – a few post-show validation nerves are natural. But Sultana has just come out the other side of months of COVID-induced insecurity. You see, Sultana feels at home in a world of back-to-back touring and hustling. For the last four years, if they weren’t in the studio, their calendar was carefully constructed, every other moment of their schedule was full. And then… nothing.

“I felt like I’d just fell off the face of the earth, after this massive tour where I was just so burnt out and I was just being really, really sensitive and sad,” Sultana admits. “I just didn’t realise that I’d spent so much time inside my own head. I felt like I wasn’t being believed in anymore.”

“I felt like I wasn’t being believed in anymore.”

This vulnerable feeling of erasure was always going to be catharised on their second album, Terra Firma, released last month. You can hear Sultana’s unpacking of it on the track “Maybe You’ve Changed”. “Why don’t you believe in me no more,” Sultana sings over a swelling melody that grows like the goosebumps you get. The song, which has since caught the eye of a few sync managers, was a career turning point; Sultana realised it wasn’t actually the fans who had stopped believing.

“I didn’t believe in me anymore,” Sultana confesses. “[…] I just felt this friction, like I couldn’t win and everything was against me. And that everyone hated me. And I was just hating on me. And I was just resisting the change that was inevitable.”

Sultana is still unpacking the insecurity and pain, sometimes consciously, sometimes subconsciously. “My grandfather was in my dream the other night,” Sultana leans back, and I’m not sure whether they’ll elaborate. “It was a weird dream. It was a scorpion, a white jaguar, and a black jaguar in my dream. The scorpion is representative of self-loathing, you know, the dark things that you feel about yourself. And the jaguars are the yin yang.

“[…] The white jaguar represents needing to treat yourself with more compassion and the black jaguar was the opposite of that. Showing me that I’ve been feeling really insecure about myself and feeling really forgotten because of the whole year. And my grandfather was in that dream too; that was before I woke up for the show yesterday.”

Tash Sultana performing at Red Rocks, Colorado – September 25th, 2019. (Photo by Dara Munnis)

Sultana speaks in a tone that is entirely different to the way they sing. Their speaking voice bounces off the nearest object before it reaches you, friendly, and sincerely Australian. Sultana’s singing voice envelops you like water.

On paper, Tash Sultana’s music isn’t commercially-driven. The 2018 single “Blackbird” is almost entirely instrumental and the vocals in “Jungle” only kick in after the two-minute mark. But a billion streams and a spot on Coachella suggest the mainstream has indeed locked on. For Sultana, global ubiquity has never been the goal, they’re happy to simply play music and make a living from it, but there’s a sense that they always knew it was written in the stars. Even Sultana’s friend, fellow artist Josh Cashman, picked up on it when they first met.

“From the day that I saw Tash perform at The Espy to even now, I knew that that was what was going to happen. That there was going to be a moment where the whole world was going to know about Tash.” Cashman speaks to me over Zoom from Victoria’s Gippsland region. “Tash knew that too I think, so did the people around them.”

Cashman first met Sultana at one of their regular Tuesday night shows in Melbourne’s St Kilda in 2014. It was The Espy’s regular night, ‘Brightside’, where five acts were each paid $20 and the hotel offered half price steaks. Cashman hugged Sultana after their set – “We didn’t even speak or anything,” he smiles. Cashman is a deep thinker, just like Sultana, and it wasn’t too long until the pair’s friendship was set: they surfed, skated, jammed, and even toured together. Now, there isn’t a week that goes by where the two don’t speak.

“As time has gone on I’ve seen the opposite of what you’d expect someone would do when they become successful,” Cashman says pointedly. “You’d think they’d become very egotistical, very like ‘my shit doesn’t stink’. Honestly, Tash has done the complete opposite over time.”

Cashman and Sultana wrote a song together in 2014, “More Than I Should”, and posted it on YouTube. It’s about falling out of love with the one you’re with. The track was revamped together at Sultana’s studio for Terra Firma – the pair faced each other to record the harmonies, holding a mic each. They decided to give their song a new name, “Dream My Life Away”.

Tash Sultana performing at RBC Echo Beach Toronto – May 31st, 2019. (Photo by Dara Munnis)

Tash Sultana may have been just three years old when they picked up a gifted guitar from their late grandfather, but it was Lana Del Rey who inspired a business plan at the tender age of 13. Lana Del Rey got her start playing every single open mic night that would have her in America, back when she was a teenage Lizzy Grant.

Sultana holds their hands up, stacking them with a big tall gap in between. “I wrote a big list of a Sunday to Saturday schedule of every fucking place in Victoria that did open mics on that night.”

Sultana’s father, a ‘your word is your bond’ type figure who emigrated from Malta in the Seventies with dreams of owning his own business and raising a family (he achieved both), carted his child off to every open mic night on that list. Tash Sultana played and wrote music endlessly as a kid. They would burn CDs every day at the family computer and sell them for $5 a pop every night. Still in high school, Sultana was a well-liked student and the class disrupter. They questioned everything, from the uniform they wore to the way their music teacher wanted exact replicas of songs, not unique renditions.

“The music teacher at my high school really didn’t like me,” Sultana flashes that 1,000-watt smile of straight pearly whites. “I think he could see something in me that just needed… maybe a little bit more discipline and focus to the criteria. But I was always anti the flow of the general direction. Why herd sheep? What the fuck is this musical criteria going to get me? I’m just going to be playing like every other person in this classroom.”

Tash Sultana performing at Ziggodome, Amsterdam – July 6th, 2019. (Photo by Dara Munnis)

Sultana worked smart, not hard, in high school. They took the fewest number of subjects necessary for a passing grade and didn’t even turn up to the graduation ceremony – “I actually don’t even have my graduation certificate.”

After high school, Sultana had no plans to join the stereotypical workforce and they were in the midst of a four-year stint dabbling in drugs that would last until age 21. That stint has been well-covered and focused on by the media over the last few years, a sticking point Sultana dislikes.

“They’ll grab one thing and they’ll run with that for fucking years and then every other journalist gets their information from this tiny little seed,” Sultana speaks with rapid-fire veracity. “And then four years have passed and it’s just like well, that story doesn’t represent where we’re at right now, so stop fucking asking me about magic mushrooms, you know what I mean?”

Back then, straight after high school, Sultana’s mother voiced her concerns at her child’s meagre open mic night earnings. “[She said], ‘You’re not going to get by selling four CDs for $5 and making $20 are you?’ And I thought, ‘Yeah, I am actually. I just got to play to more people’.”

Sultana watched fellow Melbourne duo The Pierce Brothers take over Bourke Street Mall in Melbourne one day with a busking set. They made the decision to have a crack, acoustic guitar in hand. “It didn’t really get anyone’s attention to be honest; and I thought, well, that’s no good,” Sultana squares their shoulders. “That’s not going to fucking get me my dreams.”

Tash Sultana performing at The Greek Theatre, San Francisco – September 29th, 2019. (Photo by Dara Munnis)

On Tash Sultana’s 18th birthday, their father continued his annual ritual of saying “you can have one thing” inside a music store. In the past it had been things like a banjo, a black Fender Squire, even the second-hand 12-string acoustic Maton guitar that Tash uses onstage to this day. But this particular birthday ignited a change of pace. They put down the new banjo they were considering and picked up a two-track RC-30 Roland loop station.

“[My dad said], ‘I reckon you’re making a really bad decision buying this loop station, you’re not going to use it.’” Sultana disagreed. “I said, ‘I don’t reckon I am.’” The loop station became a street stopper across Australia. Sultana took home thousands of dollars each time they busked and became financially independent, paying for broken strings, new instruments, plane tickets… Sultana had found their people, and their team at Lemon Tree Music and Sony for the world, and Mom + Pop in North America.

Sultana speaks with a rap-like rhythm when they detail the DIY approach to their career. Spit-firing their past hustles into simple, compartmentalised beat boxes. “We planted all these little seeds along the way, to play these gigs to 50 people, 100 people, 200 people, no one… Cancelled festivals, in the rain, in the hail, in the thunder, in the lightning, in the heat waves. Shit breaks down in the middle of the show. The sound’s shit. I forgot the lyrics. I had too big of a night the night before. I’m fucking supporting this person, that person, getting on festivals,” they take a breath. “And then I think I’ll write this song in my bedroom one day called ‘Jungle’. And I thought maybe I should record it on my phone.”

That iPhone 4 recording from Sultana’s living room in May 2016 went viral in a week. It clocked one million views in five days and now has 94 million plays on YouTube. It inspired a barrage of fans to text in to triple j to request the song, it placed at number three on the triple j Hottest 100 for 2016, landed on the soundtrack for the FIFA 18 video game, and helped send their Notion EP to number eight on the ARIA chart.

Sultana is a spiritual being, there’s no doubt about it. They’re not religious, but their connection to Earth, to mysticism, is written all over every artwork and release title from Flow State, a psychological state of full immersion to Terra Firma, solid ground. “Sometimes I think I should probably relax on the deep meaning shit,” they laugh. “Not everything has to have a really deep symbolic meaning, that’s just the person that I am.” But Sultana is also business-minded, and aware of the importance of building ‘Tash Sultana the brand’.

Whether it’s the team-up with Fender for their own signature guitar, or the partnerships with PlayStation and Commonwealth Bank – or the guitar prizes they’ve given away to fans for unique musical takes on Terra Firma singles – Sultana isn’t just at the boardroom table, they’re making the calls. In fact, Sultana tells me their label and publishing deals are now fully recouped and that they’re a “free agent”, meaning they’re able to re-sign, sign elsewhere, or even release wholly through their own label, Lonely Lands Records, which they launched in May 2019.

“Sometimes I think I should probably relax on the deep meaning shit.”

Sultana subscribes to the thinking that passion, desire, and sheer commitment are the three ingredients needed for achieving any goal. “You can ultimately be whatever the fuck you want. […] I just wanted to acquire as much knowledge about music as possible,” they say. As far as self-taught multi-instrumental musicians go, Tash Sultana could give world record holder Neil Nayyar a run for his money.

Sultana plays over a dozen instruments, writes and records almost autonomously, and they’re not a hit chaser – with the exception of one song. Following the release of “Jungle”, they felt the pressure to follow it up with another hit, another commercial radio takeover. “They needed a single,” Sultana deadpans, talking of the radio industry. “Otherwise you know, you’re not going to get on the air. ‘Quickly, go make one.’”

Sultana wrote “Murder to The Mind” less than two months after “Jungle” hit the ARIA Top 30 in 2017, a melange of beat-laden soul with jivey detours into jazz and rock‘n’roll territory. “That was kind of what that song was. ‘Go record something quickly and put it on the air,’” Sultana admits, before adding, “I’m still happy with it, don’t get me wrong.” You just won’t catch them playing the song live. “I tried to top [‘Jungle’] for many years afterward and then I thought, I’m not being authentic, I’m just trying to make another jam that’s going to be like that.”

“I tried to top [“Jungle”] for many years afterward and then I thought, I’m not being authentic.”

Tash Sultana performing at The Shrine, LA – December 2nd, 2018. (Photo by Dara Munnis)

Tash Sultana poured their heart and soul into the latest record. Finished in 200 days in Sultana’s own bespoke Melbourne studio in the middle of August last year, they worked tirelessly, sometimes six days a week on Terra Firma. They enlisted Flow State engineer Richard Stolz as their right-hand man for mix engineering along with just a handful of co-writers; Josh Cashman on the aforementioned “Dream My Life Away”, Dann Hume, and Matt Corby on “Pretty Lady”, “Crop Circles”, “Beyond the Pine”, and “Greed” and high school friend Jerome Farah on “Willow Tree”.

It’s brand new territory for Sultana, who single-handedly composed, arranged, performed, and executive produced every track on their debut album. “All I want to do is collabs with people,” they say, eyes lighting up. “I love it. It just opened up this can of worms that I didn’t even know was a can of worms.”

As we talk, Sultana’s fiancée Jaimie comes up in conversation many times. The pair live together in Melbourne, admittedly neglecting the vegetable garden on the 10-acre lot but skating on the half-pipe ramp when the mood takes them; and when it’s not in need of repair, like it is now. According to Sultana, Jaimie is their polar opposite when it comes to temperament. She’s ordered and a realist, Sultana is a dreamer and “a million miles an hour”.

“My life made complete sense and the person who I was meant to be came out when we met,” Sultana says. “[…] She just cuts the shit, you know. You cannot lie to her. Don’t even try. I’ve seen people try and do it.”

There’s a lot of Jaimie on Terra Firma, specifically “Beyond the Pine” and “Let the Light In”, where Sultana reveals the pair’s personal phrase for one another. “When I met her we just used to have this joke that we were each other’s Sunday. The best day of the week,” Sultana chuckles. “And then it turned into Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and forever.”

Tash Sultana performing at Ally Pally, London, UK – June 29th, 2019. (Photo by Dara Munnis)

When we head back inside, out of the heatwave, Sultana locks eyes with Jaimie over on the couch and walks over instinctively to give her a kiss. Sultana’s hair falls over their faces like a privacy curtain.

It’s hard not to view Tash Sultana as a human of integrity, a trait perhaps passed down from their father along with those vivid blue eyes. Sultana seems in no rush to become their final state; the way they study their dreams, their vulnerabilities, their identity. Growth is the most important thing to them, yet every iteration of that growth is embraced.

“I am me and I would never live a life that I am truthfully, if I wasn’t fully and utterly, and unapologetically the person that I am.” Sultana takes another sip of the herbal concoction for their throat. “And I encourage everybody else to be that way. Because you’ll never ever live your fullest truth and desire and really achieve success unless you’re truthful with yourself. If I died tomorrow,” they take pause. “I’m pretty fucking happy to be honest.”