The noise that a helicopter makes resonates differently here in Los Angeles. The blades reverberate through our neighborhoods more forebodingly here, often conjuring images of police and media surveillance. You hardly ever hear a chopper and think that something is going right. Typically, the sound evokes calamity.

After this hazy Sunday, when the sun never broke through the clouds and mist, I suspect that a helicopter’s echo will take on an even more harrowing significance in L.A. Nine people, including the pilot, died in a horrific crash on a hillside in the suburban enclave of Calabasas. Two of those aboard were 13-year-old Gianna Bryant and her father, Kobe, arguably the best Los Angeles Laker ever and, without a doubt, the city’s most beloved sports figure.

Related: Scenes From the Kobe Bryant Memorial Outside Staples Center on January 26th

Los Angeles had already been preparing for mourning, as the Grammys were planning to honor its slain native son, rapper Nipsey Hussle, that evening. The late Ermias Asghedom, who was murdered last March in South Los Angeles, also won his first Grammys — for Best Rap Performance and Best Rap/Sung Performance. The sight of seeing his family accept them on his behalf seemed like a preview of what we’ll see later in 2020 when Bryant, who was only 41, is inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in absentia.

In Nipsey and Kobe, there is a poignant parallel: two lives cut much too short — but also before the world at large truly got to comprehend the totality of the men. They both were men with extremely flawed pasts who had sought redemption in their own ways. And they had acts yet to live out. But we’ll never see them. We’ll never fully know who they could have become.

That will have a lasting effect on our understanding of who Bryant was. We knew about the work ethic that drove him to greatness during his 20 years with the Lakers, the guy so physically unshakable that he once shot and made two free throws standing on a blown Achilles tendon. I didn’t start as a fan of Bryant’s. When I first saw him play as a high schooler in Philadelphia in 1996, during my college days, I didn’t care much for his arrogance. (In 2016, Rolling Stone celebrated Bryant after his last game as “the NBA’s All-Time Asshole.”) But it was impossible not to respect his amazingly varied collection of skills on the court. What I actually admired most about Bryant’s game was what it lacked: fear and abandon. He wasn’t Michael Jordan, but he was arguably the bridge between him and current Lakers star LeBron James, shooting like an assassin. His defense had the persistence of an irritating little sibling. He was fierce, smart, and focused.

We could discern much about Bryant from his consistent play and his dry yet revealing sound bites. But this was a complicated and nuanced man, who was fluent in multiple languages and had an intellectual curiosity, who also spoke to my inner nerd. That was the side of Kobe who I’d become eager to see flourish in his post-Laker life, especially since I’d become a Los Angeles resident.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

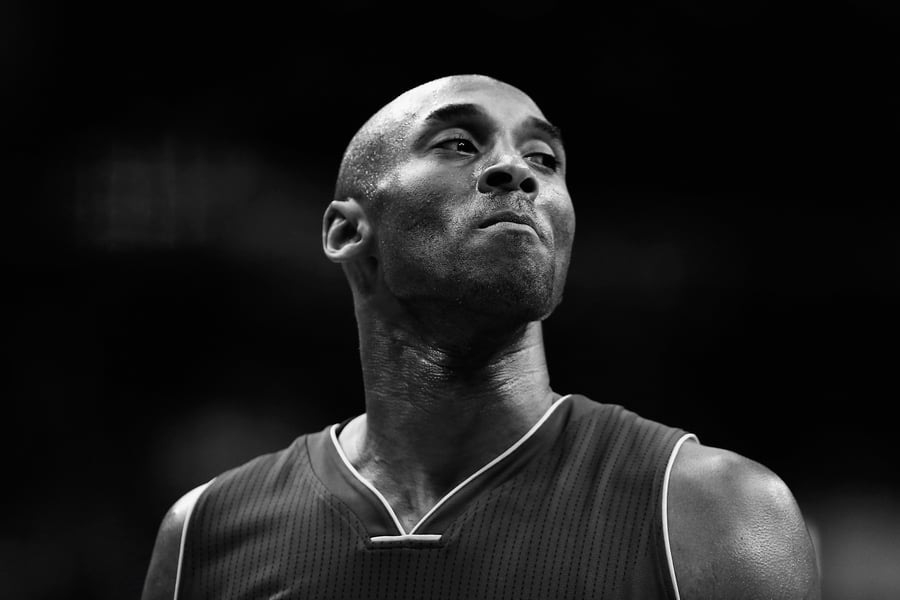

Kobe Bryant and his daughter Gianna Bryant died in a helicopter crash on Sunday, January 26th.

Photo by Allen Berezovsky/Getty Images

Unlike many athletes who struggle in civilian life, Bryant had been thriving. Had he been able to speak at his Hall of Fame induction, he may have mentioned how his signature relentlessness continued to drive him after his retirement in 2016 toward an Oscar win for his short animated film, Dear Basketball. He continued to help grow basketball globally and worked with various philanthropic endeavors and a venture-capital firm. Most of all, though, Bryant was a conspicuously involved father, frequently courtside with Gianna at Lakers games, and coaching her and other girls at the Mamba Sports Academy, where their helicopter was headed on this awful Sunday morning.

Yet all that only speaks to what Bryant already had been doing. Who was he going to become, though? I thought he could and would become even more. We already knew that he was a role model to athletes everywhere for his indomitable competitiveness. How would that legacy have evolved as the hero-baller turned into an elder statesman of the game?

More broadly, would Bryant have sought more discernible redemption for the most disgraceful episode of his career? In 2003, a 19-year-old employee at a Colorado hotel where Bryant had been staying, brought forth a credible and detailed accusation of rape. Bryant admitted adultery, but never criminal guilt. He settled her civil suit with a written apology after the criminal case was dropped, all due to the fact that the accuser’s name had been dragged through the mud. This is why many survivors of sexual violence had complicated emotions Sunday as adulation poured out for Bryant after his death. (We can mourn and recognize greatness while at the same time acknowledging the pain that someone caused.)

It may sound like wishful thinking, but he had shown the capability to change his mind on a social issue and to be vocal — namely, altering and apologizing for his initial, tone-deaf stance on the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin — when confronted with a dissenting opinion. In 2011, he’d admitted using a homophobic slur toward a referee “wasn’t cool and was ignorant on my part,” then leaned on his fans to mature similarly. Recently, he hadn’t been shy in sharing his political disagreements about President Trump. Could Bryant have also been pushed to take more direct action to stop sexual violence, or done so of his own accord, and what would that action have looked like? Would he have been embraced?

All of these will remain unanswered questions, and his will remain an incomplete life. So many of us surely wanted to see who Bryant would become over the years, but we’ve been robbed of that chance. The principal tragedy of his death will always be a father and husband stolen from his wife and daughters, but the rest of us lose the chance to see one of the greatest players of all time use the drive that made him superb and see how that would manifest off the court.

In a way, that was happening most indelibly in the person of Gianna. Kobe’s second act took an even more brutal hit with the death of his young daughter, who so loved the game that defined her father’s life. She reportedly aspired to play at basketball giant UConn and later in the WNBA. (Perhaps it was his daughter’s growth as a player that led Bryant to embrace the women’s league as he did, saying that WNBA players like Diana Taurasi and Elena Della Donne could play in the men’s league.)

Bryant recently told fellow NBA retirees-turned-podcasters Matt Barnes and Stephen Jackson how Gianna had basketball on every night in the house, and had pushed him to return to games at the Staples Center after his number-retirement ceremony. It was clear that, through her lens, he viewed the game differently.

In 2018, Bryant told Jimmy Kimmel how Gianna vowed to carry on the family name: “The best thing that happens is when we go out and she’ll be standing next to me and fans will come up to me, like, ‘Hey, you gotta have a boy, you and [Vanessa, his wife] gotta have a boy — somebody to carry on the legacy and the tradition,’ and [Gianna] will be, like, ‘I got this. We don’t need a boy for that. I got this!’ “

Now that’s all gone.

Today and in the weeks ahead, there will be comprehensive and lyrical encapsulations of what Bryant meant to basketball. There will be laudatory mentions of his five NBA titles, the retired numbers 8 and 24, the 81-point game, the two Olympic gold medals, and the 2008 MVP season. Those will capture his greatness on the court, a career that will remain the stuff of legend for as long as people on this earth care about sports.

But stars like Bryant are possessed of a unique drive and intelligence. The vicious blow we feel from their early deaths only remind us of what has been so cruelly truncated. They have professional legacies that we understand, but as people, we are just getting to know them.

We have lost the chance to know nine people better. Bryant was only the most famous. His daughter had perhaps the most potential. On this Sunday bereft of sun in Los Angeles, it is worth remembering just how much has been left unfinished.