In the Democratic National Convention’s reimagined fairy tale, “Goldilocks and the Beltway,” President Joe Biden played the part of the porridge. “I was too young to be in the Senate,” he quipped, and now he’s “too old to stay as president.” Biden’s candid admission was met with a standing ovation from those eager to usher him offstage — but this presidential historian can’t help but feel alarmed.

I don’t think the decision to shuffle out of office at 81 should have been Biden’s to make, nor should it be left to the Republican rival, Donald Trump — a convicted felon who, if successful, will be 82 at the end of his second term … which he may not consider his last. If lawmakers don’t codify an age limit for the presidency — or remove the minimum requirement of 35 — Biden’s farewell might be remembered as the last coherent thing said by a sitting president.

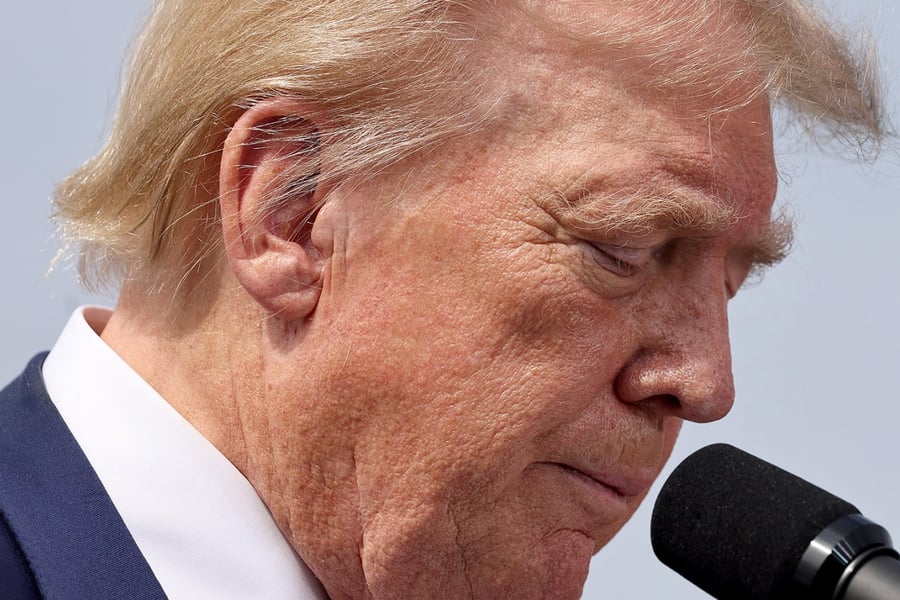

At 78, Trump’s age lends an unnerving weight to his vice presidential running mate. J.D. Vance, a mere 40 years old, is comfortable brandishing his radical stances on pivotal issues like a national abortion ban, even under Trump’s allegedly moderating influence. This foreshadows a chilling scenario: should Trump’s tenure end prematurely, a President Vance stands poised to transmute his extreme beliefs into the iron-clad policy of the land.

I know how I sound — like I’m a framer at the Constitutional Convention. The founding ageists’ debate over the presidential age minimum at 35 has been overlooked and forgotten for far too long: George Mason, convinced that wisdom required at least 35 rotations around the sun, faced off against future Supreme Court Justice James Wilson. Wilson, fearing the stifling of “genius and laudable ambition,” invoked the British wunderkind William Pitt the Younger, who became prime minister at a sprightly 24. But invoking British examples to recently liberated colonists was about as effective as using a teacup to bail out the Boston Harbor. Mason’s argument that on-the-job Congressional training was essential — but time-consuming — proved more persuasive.

Mason, a paragon of paradox, refused to sign the Constitution and rallied against its ratification in his home state.

Many presidents, Trump included, have sidestepped congressional apprenticeship entirely, making Mason’s insistence on legislative seasoning seem quaint. And James Monroe’s actuarial prediction that dynastic presidencies were unlikely due to men typically expiring in their late 30s? John Quincy Adams ascended to the presidency during Monroe’s final year in office, becoming the first presidential son to follow in his father’s footsteps.

Had Mason deigned to grace the Second Continental Congress with his august presence in 1776, as George Washington fervently wished, the chorus of youthful revolutionaries might have been unceremoniously muted. Picture Patrick Henry, all of 29, his impassioned cry of “Give me liberty or give me death!” silenced before it could echo through history. Imagine Thomas Jefferson, a sprightly 33, barred from crafting the Declaration of Independence. Alexander Hamilton, 21, along with the cadre of spirited young rebels propelling the war, might have been sent off to bed with their revolution.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Why didn’t the framers include an upper age limit? It never came up. Picture them, powdered heads bent over parchment, inventing a country. In their world, reaching one’s 50s was cause for celebration; the idea of septuagenarian presidents was as far-fetched as moon landings. They weren’t equipped with crystal balls to foresee how modern medicine would extend life expectancy. The notion of cognitive decline in leadership was irrelevant. If it had been front of mind, they would have left it to Washington, the ever-reliable precedent-setter. He left office at a spry 64 years old, and they reasoned future leaders would simply follow suit. The assumption that common sense would prevail in politics is a quaint notion that’s aged as well as their knee breeches and tricorn hats.

The honor system works — until it doesn’t. Inspired by Washington’s two-term precedent, 31 presidents followed suit until Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s unprecedented four-term tenure was abruptly ended by his death in office. This prompted the 22nd Amendment, which formally entrenched term limits into law. Similarly, when Lyndon B. Johnson, a man of 55 who had survived a near-fatal heart attack, stepped into power after John F. Kennedy’s assassination, he exposed vulnerabilities in the presidential succession line. The precarious health of the next in line — a 71-year-old Speaker of the House and an 86-year-old Senate President Pro Tempore — spurred the ratification of the 25th Amendment in 1967, streamlining the transition of power to ensure stability.

The 25th Amendment, designed as a failsafe for presidential incapacity, has proven to be merely decorative. In theory, it outlines the transition of power should a president be unable to fulfill official duties, but in practice, partisanship has rendered it toothless. It was allegedly discussed during Ronald Reagan’s second term as signs of his cognitive decline surfaced, but no action was taken; Reagan, then the oldest president, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s just five years post-presidency. After the January 6th insurrection, calls from Democrats for then-Vice President Mike Pence to invoke the 25th fell on deaf ears, underscoring the amendment’s practical limitations in the thick drama of American politics.

According to the Pew Research Center, the public prefers presidents who aren’t senior citizens. About half the nation believes the sweet spot for a president is their 50s, while another 24% give the nod to candidates navigating their 60s. The debate barely flickers between parties. A paltry 3% of U.S. adults advocate for command-in-chiefs cruising in their 70s or beyond, hinting that perhaps it’s high time Congress entertained the thought of etching an age cap into the legislative books.

Capitol Hill has morphed into a veritable geriatric gymboree, presided over by a corps of “pick me” handmaidens who’d sooner play hide-and-seek with grandpa’s car keys than have his license revoked. Their misguided logic suggests preserving dignity until it’s subpoenaed by the great caucus in the sky. (Case in point: the late Diane Feinstein). But what if our doddering leader stumbles upon those hidden keys — which, in this high-stakes game of national security, are actually nuclear codes — and decides to take a joyride straight into metaphorical traffic, with “traffic” here standing in for the entire human race? RAND Corporation has found anyone with security clearance can become a threat with the onset of dementia. In this absurdist political theater, we’ve entrusted our nation’s most sensitive secrets to a ticking time bomb of cognitive decline, hoping against hope that senility won’t strike before the next election cycle. Safeguarding an individual’s dignity — and a political party’s grasp on power — has become a threat to our collective survival.

Mason’s legacy as the original ageist of American politics serves as a potent reminder that genuine representation is a labyrinthine, often paradoxical endeavor. As we navigate this thorny issue, more prudent paths beckon: Congress could institute an upper age ceiling, dismantle the minimum age requirement, or engineer a system rooted in principles that soar above arbitrary age constraints — championing inclusivity, adaptability, and cognitive diversity as cornerstones of leadership. As we chart our course, let’s not forget that wisdom isn’t inherently bound to wrinkles but folly has demonstrated a remarkable ability to transcend generational boundaries.

Alexis Coe is an American presidential historian, senior fellow at New America, and the author of, most recently, the New York Times best-selling You Never Forget Your First: A Biography of George Washington.

From Rolling Stone US