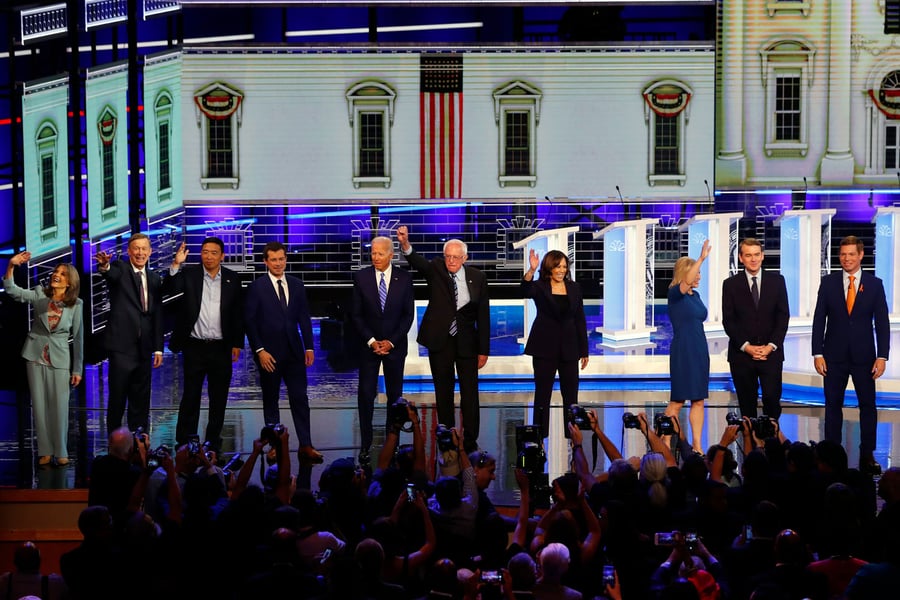

Take your mind back there. Miami. June 2019. Two nights, 20 candidates. A portrait of the Democratic Party in miniature assembled onstage, mics on, ready to debate.

They are U.S. senators and House members, governors and a mayor, a refreshingly human economic futurist and a self-help guru best known as Oprah’s spiritual adviser. They are young and old, black and white and Asian and brown, wealthy and in debt, gay and straight, war veterans, hailing from all parts of the country. They are, as Democratic chairman Tom Perez proudly points out, “the most diverse field in our nation’s history.”

Feels like a lifetime ago, doesn’t it?

There was a sense of possibility and optimism on that stage. Fast forward six months. The leading Democratic candidates are all white. Three are men, and three are older than 70. Meanwhile two old white billionaires are buying their way into contention by spending hundreds of millions of their personal fortunes. At this point four years ago, the top candidates for the Republican nomination were more diverse than the Democratic frontrunners today. Many politicians hailed as the Future of The Party — Kamala Harris, Cory Booker, Julián Castro, Kirsten Gillibrand, Beto O’Rourke — are gone, exiting the race before a single vote was cast.

“They wanted a big, fluid, multicultural field — they didn’t get it,” says Jeff Roe, a Republican political consultant who ran Ted Cruz’s 2016 presidential campaign. “They wanted a new generation of leadership — they didn’t get it. They didn’t get any of the things they wanted.”

Instead of writing the 5,000th story trying to predict the outcome in Iowa or New Hampshire, Rolling Stone asked dozens of people — campaign staffers, volunteers, activists, pollsters, party officials, voters — to reflect on the campaign so far. We wanted to know: What happened? Why did the Democratic primary get so white? Why have known brands and familiar faces led the pack? Why are so many Democratic voters undecided after a year of campaigning? Did the Democratic National Committee screw this up? Or is this what the voters wanted?

Voters are angry, afraid, and exhausted

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

The daily assault of terrifying Trump headlines. The endless partisan combat in Congress. The toxic conversations on social media. Felt the urge lately to hurl your phone into the nearest body of water after it lit up with the latest push notification from the New York Times? You’re not alone.

Going into the 2020 primaries, Democratic voters are fueled by the most primal of emotions: fear and anger. Fear and anger about the state of the nation, the conduct of the president, the blind loyalty of Trump’s Republican allies, and the uncertainty of what comes next.

“They are the two most prevalent emotions out there,” says a former senior staffer on a now-defunct Democratic campaign who requested anonymity to talk candidly about the campaign he worked on, the other candidates, and the DNC. “They both have to do with Donald Trump: they’re angry at him and afraid he’s going to win again.”

Voters are also burned out by the events of the past three years. “I think many Americans are exhausted by our politics,” says Andrew Yang, the insurgent Democrat who has built from scratch perhaps the only true grassroots campaign of the 2020 race. Yang says he sees Trump fatigue as one of the reasons his message — that the president is a symptom of bigger changes in our country and economy, including the rise of automation and artificial intelligence — has resonated. “There is the sense that Democrats are painting [Trump] as the cause of all the problems, and many Americans are just fed up because there’s more of a focus on Trump than on their towns and cities.”

Ellen Montanari, a progressive activist in southern California who has worked closely with Indivisible, says she believes Trump’s madman approach is a deliberate. “He knows that by bombarding us with all of this, we can’t concentrate,” she says. “It’s a brilliant ploy.” And it’s working. Montanari says she sees signs of burnout among the activists and volunteers she works with. She hears a common refrain from people she knows: “I just want to go back to a world where the government is in the hands of grown-ups.”

The challenge for the Democratic nominee is this: Can he or she transcend the Trump distraction machine and rekindle the energy seen in the Women’s March, in the post-Trump explosion of grassroots groups, and in the 2018 midterm election?

Democrats are obsessed with electability — but have no idea what it means

When George Hamblen drives around southeastern New Hampshire, where he lives and runs his town’s Democratic Party chapter, he sees far fewer yard signs for Democratic candidates than he did in years past. Yet the campaign events in his state are jam-packed. Warren, Amy, Tulsi, Mayor Pete, Yang — they all draw standing-room only crowds, people spilling out into the parking lot.

What’s going on here? It’s that pesky word: electability. No one quite knows what it means, but it’s what so many Democratic voters are seeking and holding out for.

“Quite frankly, I would vote for anyone against Trump — and a pulse is optional,” Ellen Montanari, the southern California progressive activist, says. “I just need to have someone in office other than him. That’s number one for me.”

With fear and anger come a sense of caution, calculation, a belief that this is a time to vote with your head, not your heart. “People are so scared of getting it wrong that they’re going to take every piece of information into the calculus of electability ultimately,” the same former presidential campaign staffer says. Every poll, every town hall, every debate performance — all of it gets added into an ever-shifting set of calculations by voters. “Iowans are going to wait to make their decision until the day of the caucus,” the former staffer says. “Granite Staters are going to take Iowa’s result into account and then make their decision as they walk into the polling booth.”

But what does electability look like? Is it experience? Policy plans? Charisma and confidence on the debate stage?

Talk to Democratic voters and you get the sense that electability means something different to each person, fluid and ever-changing, if it means anything at all. “At this point I go back to Socrates: ‘I know that I know nothing,’ ” says Chris Dueker, a New Hampshire voter who describes himself as progressive. “I feel a lot of people are claiming that this candidate can’t win, only my candidate can win.”

“My feeling at this point is I know I don’t know and they don’t know,” Dueker adds. “Electability is completely impenetrable to me. I say this with some humility. I would prefer a progressive, but maybe Biden would be the best candidate.”

The shape-shifting concept of electability is one reason why so many candidates have enjoyed a brief bump in the polls only to lose their spot in the limelight to another candidate. The former senior campaign staffer says this was largely college-educated white voters “basically shopping for the flavor of the month” — first Kamala, then Beto, then Mayor Pete, then Warren, and on and on. “It’s the very same people moving around,” the former staffer says. That’s the fickle thing about electability: it’s self-reinforcing and self-defeating, as quick to materialize as it is to evaporate.

Becky Bond, a progressive consultant who advised Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign and Beto O’Rourke’s 2018 Senate run, says there’s a paralyzed feeling among Democratic voters who recognize the stakes of the election and feel a responsibility to pick the “right” candidate. “They don’t want to make the wrong choice,” Bond says. “People are waiting and not getting fully invested behind someone until there’s a nominee.”

The DNC’s rules backfired spectacularly

In late 2018, DNC Chairman Tom Perez unveiled the revamped rules for the upcoming Democratic primary debates. Perez pledged that the DNC’s debate rules would “give the grassroots a bigger voice than ever before” and “put our nominee in the strongest position possible to defeat Donald Trump.”

Until Democrats pick a nominee and that person faces off against Trump, it’s impossible to say for sure how well Perez’s reforms panned out. But a year later, what’s beyond a doubt is that they did not empower the grassroots and they replaced old gatekeepers with new ones.

Because of these new rules, the most powerful people in the primary up to this point have arguably been the pollsters. Polls are, of course, a partial reflection of the electorate itself, but if 2016 taught us anything, it’s that polls can mislead, give false confidence, and miss entire chunks of the voting-age population. For the past year, campaigns lived and died by the latest Quinnipiac or Fox News or CNN poll; journalists built devoted followings around reporting on polls and interpreting the DNC’s obscure guidelines for which polls did and didn’t count toward the debate. And for voters, polls came to represent — rightly or wrongly — a proxy for viability, strength, the ability to beat Trump.

The DNC also required that candidates meet a threshold of individual grassroots donations to make the debate stage. Candidates and staffers say they understand why the DNC used this metric as a stand-in for grassroots support, but they complained that the donor requirement — like the polling threshold — gave a leg up to candidates who already had high name recognition and a preexisting network of small-dollar donors to draw on.

Candidates without both of those qualities entered the race at a disadvantage. Instead of spending money to build a field operation in Iowa or make an early play for California’s delegates, campaigns spent money to buy email lists to fundraise off of in order to meet an arbitrary donor target. Jenna Lowenstein, Cory Booker’s deputy campaign manager, wrote on Twitter that on the day the DNC doubled the donor threshold to 130,000, she “literally Control+A+Deleted a plan for a whole entire early game, early-state persuasion strategy, and used the money to buy email addresses instead.”

West Coast governors such as Jay Inslee of Washington state and Steve Bullock of Montana might have suffered the most from the DNC rules. Both are highly accomplished politicians with progressive records that should make an Iowan swoon. Unlike U.S. senators, though, governors don’t get to use nationally televised congressional hearings to boost their profiles or enjoy easy access to the bulk of the political press corps now located in Washington and New York. Despite having a compelling story to tell, Inslee and Bullock dropped out of the race rather than miss qualifying for the debates.

“The thing that surprised me the most is that brand name meant so much in this primary,” says Jennifer Fiore, the former adviser to Julián Castro’s campaign. “There isn’t a single top contender who didn’t come into this with a major brand already identified in Democratic politics. It used to be that somebody new could really break out in a primary. It’s where Obama came from, Kennedy came from.”

The DNC provided more fodder to its critics when it recently announced it would eliminate the donor requirement for its February debate. There’s an argument to be made that it makes sense to adjust the debate rules after voting starts and include primary election results as a new metric for measuring viability. But the upshot is an old, white, self-funding billionaire in Mike Bloomberg will now benefit from new rules that help him get on the debate stage (if he bothers to show up) after a slew of younger candidates, candidates of color, and female candidates effectively saw their campaigns ended by a lack of cash and a failure to qualify for future debates.

Perhaps the best solution in the simplest one: Get rid of the debate requirements. Or get rid of debates altogether in the run-up to the actual primary. Stick to televised town halls for individual candidates or forums that highlight a single issue like climate or gun safety. Doing so would eliminate the cagematch faux-drama of the cable-TV debates and give citizens more of an opportunity to question the candidates themselves.

Political journalism never learned the lessons of 2016

Sometime in early 2019, Jennifer Fiore, the former adviser to Julián Castro, had a conversation with a prominent political reporter. “This person said to me, ‘How are you going to handle it if Donald Trump starts dragging your candidate through the mud on Twitter? How are you going to handle the media’s coverage of that?’” Fiore recalls. She says she turned the question back on the reporter: How are you going to handle that?

The reporter had no answer for her. “It was like I had asked this question that nobody had ever thought of,” she says.

In the aftermath of the 2016 election, there was a widely shared consensus that the media bungled the biggest story of a generation. A fixation on the spectacle of Donald Trump blinded us to the tectonic changes in American culture that delivered Trump the presidency. There was a brief period of hand-wringing. There were pledges to get out of our coastal bubbles and reconnect with Middle America. But this largely meant seeking out Trump voters in Rust Belt diners — that is, applying the old model of doing things to a new reality. Instead, we needed a new model.

There was no 9/11 Commission for the press. No serious effort to reimagine how we cover campaigns and to try something new. That maybe instead of telling voters how to feel about whatever the latest breaking news was, we should shut up and listen to them. “It’s like a law of nature that you just move on to the next story,” says Jay Rosen, the NYU professor and one of the most trenchant critics of American political journalism. “Because of that, you don’t have any real inquiry into what went wrong.”

“Sleepwalking into 2020” is how the Columbia Journalism Review headlined a recent oral history about the media’s coverage of the current campaign. The most striking observation came from Ben Smith, the outgoing editor-in-chief of BuzzFeed News and a veteran political reporter. There was an odd resignation in what Smith had to say: “The media has this incredible quadrennial habit of learning all the lessons of four years ago and applying them when the medium has already moved on,” Smith said. “Things keep changing, yet we fight the last war. So I think the media is totally prepared not to repeat the mistakes of the last cycle, like giving Trump endless livestreams and letting him use provocative tweets to dominate the conversation, but I’m sure we will fuck it up in some new way we aren’t expecting.” (Smith will soon join the New York Times as a media critic.)

Smith’s critique was framed around changing mediums — newspapers to TV, TV to online, blogs to Twitter, and so on — but there’s a bigger problem at play here.

The way NYU’s Jay Rosen sees it, political journalists still have not defined what their mission and purpose is. Is success beating the competition with scoops that resonate mostly within the political class? Is it “reading the tea leaves” and predicting winners and losers? Is it regurgitating Trump’s latest attack on Biden or Bernie?

Because that’s what too much of political journalism still is. To what end?

Democrats need a plan to heal the country — where is it?

If a Democrat wins in November, no matter which Democrat it is, the task before them will be a monumental one. Trump and his allies and every organ of the right-wing media will attack the new president non-stop. “The level of racial acrimony and violence that we’re likely to see in 2021 will likely make the tea party pale in comparison,” says Ian Haney López, the director of the Racial Politics Project at the University of California, Berkeley’s law school.

The new Democratic president, the Democratic Party, and the movement that elected that president will have to reckon with this. How do you begin to reknit the country back together?

Voters and activists recognize this. They say they want to hear from the candidates about how to win over not just allies but folks on the other side of the partisan divide. It might be unfair to ask the current Democratic presidential field to have offered a vision for unifying the country while they’re still competing for their party’s nomination. But this question of healing the country is never far from mind when you talk to voters about what they want in a president.

“Who is it that has that ability to reach out to Americans, not just to Democrats but to Americans?” Ellen Montanari, the southern California activist says. “Who is it who’s reaching into the homes of everyday people? Who is it that’s going to capture their imagination?”

The point of a Democratic primary is to pick the best nominee. But in these extraordinary times, it’s not too much to ask that the first year of the 2020 campaign also point a way forward for the country, a path out of the darkness of the Trump era. There were glimmers of that kind of campaign in the spring and summer of last year, but those loftier ideas were soon pushed aside in favor of more practical concerns like polling numbers and small-dollar donors.

In a larger sense, the Democratic Party still feels trapped in 2016: the revolutionary left against Obama-era liberalism, wooing the white working class versus turning out loyal voters of color, and so on. Has the endless primary of 2020 — and the choices made to shape that primary — made it difficult if not impossible for a candidate to build the multiracial movement needed to defeat Trump and send hate back into hiding? Is this the best way to produce their nominee who can heal the country, an aspiration that feels more essential and imperative than ever?

Maybe it’s not the role of the endless primary to produce such a candidate. It should be.