“We’re the most famous band you’ve never heard of,” quips Colin Newman, singer and guitarist for punk-era futurists Wire. “Our fans assume that Wire is massive – like, we’ve all got mansions. And then there are lots of people who know groups who are more successful than Wire who’ve been influenced by Wire – yet they’ve never heard of Wire. It’s a very strange kind of fame.”

Wire have dwelled in the recesses of underground rock’s vanguard for the past four decades. When their peers in England were exploring savage maximalism, they became punk’s great self-editors – issuing their debut, Pink Flag,in 1977, which somehow improbably packed 21 songs into 36 minutes. Over the years, that record has inspired a generation of bands, including R.E.M., Spoon and a clutch of Washington, D.C., hardcore acts, to cut to the chase musically as succinctly as possible. Within a few months of Pink Flag’s release, though, Wire had radicalized their sound, incorporating synthesizers and other instruments to accentuate their songs’ moodier melodies, and in the decades since, they’ve continued to subvert and flirt with rock & roll conventions.

“I think Wire have one of the most interesting stories in music,” says former Rollins Band and Black Flag frontman Henry Rollins, a devout Wire fan who once covered Pink Flag’s “Ex-Lion Tamer.” “Pink Flag, [1978’s] Chairs Missing and [1979’s] 154 – and then onto the live songs on [1981’s] Document and Eyewitness – it’s as if it’s four different bands. I don’t know of any band in that time that evolved so much in such a short amount of time.”

Their 16th studio album, Silver/Lead – due out Friday, during Wire’s Drill Los Angeles festival – finds the group exploring fuzzy, atmospheric synths and more traditional song structures. Wire’s members have always fancied themselves to be Dadaists, thumbing their noses at tradition, but here they’ve created a work of anti-Dada – a stark inverse of Pink Flag, full of regular-length songs with bells and whistles and the heavy influence of Berlin-era Bowie. And yet, Silver/Lead songs like the urgent “Sonic Lens” and throbbing “Playing Harp for the Fishes” vibrate with inexplicable anxiety, Wire’s signature since the beginning. It’s a testament to the band’s insistence on seeing through their vision from all possible angles.

The group first developed that perspective about 40 years ago this month. The band members had been playing around London under the name Overload with a singer-guitarist named George Gill, but by Newman’s account, it wasn’t working out. “All we were playing was George’s material, and I was just a singer,” he recalls. “I thought his music was terrible, and I told him I thought it was terrible.” Wire bassist Graham Lewis recalls Overload’s music as being aggressive, and “very, very, very shouty.” Newman eventually became enamoured with Patti Smith and the Ramones, and, after attending a Damned concert at the Roxy, decided Gill had to go. So, at a rehearsal that Gill missed because he’d injured his leg after attempting to steal the amplifier of a band they’d been playing with, Newman had a chat with the rest of the band.

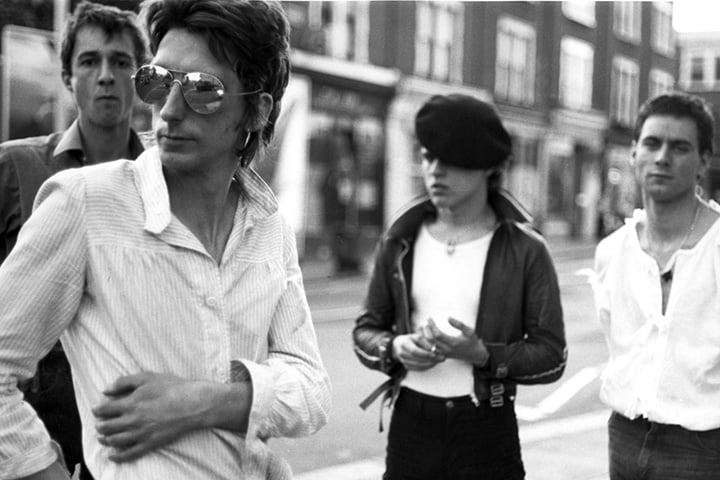

Wire (with George Gill) in February 1977. “I thought his music was terrible,” Newman says of Gill.

“I said, ‘Well I can write songs,’ and Graham said he could write lyrics,” Newman recalls. “And he handed me the lyrics of [Pink Flag’s] ‘Lowdown’ there and then, and that was the first song we wrote together.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“There was a certain amount of bravado in saying I could write lyrics,” Lewis says. “But we met the next day to rehearse, and we kept rehearsing four days a week for 12 hours a day. In a three-week period, we wrote and rehearsed something like 17 pieces. We were very excited by the limited skills we had coalesced. The group had a sound and we had to build something on it with the limited skills we had. It was like the static and the noise had disappeared.”

Once the chaos cleared, the vision of the group’s four members – Newman, Lewis, guitarist Bruce Gilbert and drummer Robert Gotobed – came into focus. “I didn’t like rock & roll music – to me it was kind of old Fifties music – but I was into psychedelic pop of the Sixties,” Newman recalls. “I knew that for Wire, I was going to have to write a very stripped-back type of song. It was very weird in the beginning, because I didn’t play guitar well. Bruce, who used to be in a blues group, played only in an open tuning – where you put one finger on the strings to make a chord – so everything was in major chords, and I couldn’t be doing with that, so I set about writing material that I thought was a reinvention of the idea of rock music. It was ditching the whole rock & roll thing and making something more straightforward, more brutal.”

“We became rather fascinated with the beginning and endings of songs and putting shocking stops in – like the one in ’12XU,'” Lewis says. “The shorter songs developed naturally. When the words ran out, Colin said, ‘That’s it.’ We went, ‘Yes, why not?’ It used to drive the punks nuts. They’d sort of get pogoing, and then it would stop. We always thought it was really funny.”

Wire played their first official concert as a four-piece on April 1st, 1977. A recording of the show, released as Live at the Roxy, London in 2006, finds the group playing a handful of raucous-yet-taut Pink Flag ragers, as well as the Ramones-y Overload holdover “Mary Is a Dyke” and hyper-speed J.J. Cale and Dave Clark Five covers. “I must say, the first gig was very inauspicious,” Newman says. “I think we played to about three-and-a-half people. I mean, the club was the size of a toilet, but still, three-and-a-half didn’t look full.”

Most of the songs on Pink Flag came out organically by trying ideas, according to Lewis. “12XU” came from counting off songs “one, two, fuck you.” “We thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be good to invent self-censorship?'” the bassist says with a laugh. “Then the ideas kept spiralling along. ‘Let’s have an intro in French [as in “Surgeon’s Girl”].’ Or, ‘This song sounds a bit Brazilian [“Brazil”], so let’s do a Brazilian version and, there you go, ‘Three Girl Rumba.’ It was an acceleration of ideas. And as we played, our skill level was going up and we were getting tighter, and the tighter we got, the funnier it was with the stopping and starting.

“Something that’s kind of lost in history is that when you would go see the Sex Pistols playing in the pubs around London, the great thing about them is it was funny,” he continues. “They were funny. And you either got it, or people hated it. For us, it was very much the Dada tradition, that it should be provocative and it can be nonsense and can be funny. And the Pistols were hilarious. They used to cover my favorite trash songs like ‘Here Comes the Nice’ by the Small Faces or something by the Monkees. It had that absurdity to it, and that absurdity really appealed to us.”

Wire in 1979. “I set about writing material that I thought was a reinvention of the idea of rock music,” Colin Newman says.

When the band finally saw the Ramones and the Buzzcocks live, they decided they needed to play even faster. Despite their apparent influences, however, the group never felt comfortable in the punk scene. “When the Heartbreakers came to London, they had a strong influence on quite a few individuals and, let’s say, it wasn’t terribly healthy,” Lewis says. “You’ve got the Stranglers and the Clash, and also the Jam. We thought those bands’ approach was conventional, because most of them were R&B-based. We didn’t want to do what other people were doing. We started absorbing early German electronic music and early Pink Floyd into what we were doing. We were more interested in Patti Smith and the Ramones, Talking Heads, Teenage Jesus – all this stuff is far more interesting to us because it was art-based.”

As the four band members continued to write in various configurations, they recognisd their sound was changing. The song “Practice Makes Perfect,” with its plodding tempo and vocal harmonies didn’t fit Pink Flag, so Wire reserved that number and the surfy, early-Floyd-like “French Film Blurred” for their second LP, 1978’s Chairs Missing, which incorporated synthesizers into the band’s sound. “It was just blatantly obvious that the Pink Flag period was done,” Lewis says. “As our confidence grew, we expanded our sound. The whole straight punk thing was becoming not so important; it was more mainstream. And it wasn’t that great. It was like pop.”

But while the group moved on in the U.K., the influences of Pink Flag had begun rippling in the U.S. In Washington, D.C., Bad Brains, Minor Threat and a young Henry Rollins discovered the band. “I can’t remember exactly what record it was that I heard first, but I suspect it was two of the early singles – one that featured ’12XU’ and another that featured ‘Ex-Lion Tamer,'” Rollins says. “The things that struck me about the were the precision, the lack of solos, the almost mocking tone of Colin Newman’s voice, the intensity of the guitar tone. They were completely full-on without being macho. It was quite a lesson to me.

“I can’t speak for other people, but I think the other people in the D.C. scene thought the band was sharp and the exactness with which they delivered their songs didn’t go unnoticed,” he continues. “The D.C. scene then and now is a noticeably intellectual one; that Wire appealed to people there isn’t at all surprising.”

Their legend also spread to the south, where R.E.M. discovered them, leading to a honky-tonk cover of “Strange” on their Document LP, and to the Midwest where Big Black eventually made a gut-rattling cover of Chairs Missing’s “Heartbeat” and the members of Hüsker Dü latched onto their uniqueness. “Wire sounded different from the early U.K. punk bands,” says Bob Mould, who discovered the band with the release of Chairs Missing. “They were more thought out, less ‘protest’ political, but equally thought-provoking. They were using a different lens for their music.”

Wire’s music also resonated on the West Coast, where the Minutemen discovered Pink Flag at a Long Beach record store and picked it up because they liked to cover. “I don’t know what we would have sounded like if we didn’t hear it,” bassist Mike Watt says. “That’s where we got the idea for writing little songs and that’s even where we got the idea of how to print our lyrics on our record sleeves.

“And the sound was incredible,” he continues. “It was like that NYC band Richard Hell and the Voidoids without the studio gimmickry, but Wire was way more ‘econo’ with the instrumentation and the radical approach to song structure. And the way Wire wrote words were artistic without being elitist; some of the slang was trippy, too. All the ‘old’ conventions from all the other ‘old’ bands went out the window after we heard Wire. They were big-time liberating on us.”

“Pink Flag is like a blueprint, and it’s simple,” Lewis says about why he thinks that era of the group struck so many musicians. “It’s unusual in its arrangements and the lyrics are unusual. You have something like ’12XU,’ which is about queerness and it’s transgender-based, not that anybody noticed. Then ‘Pink Flag’ is a complete piece of imagination, and ‘Field Day for the Sundays’ is about the real progress of the yellow press, destroying sports stars lives because of their sexual activities. I think it had a more unusual and perhaps inventive view of politics. I think that’s what attracted people, as well as the cover. Bruce and I both came up with the same image independently.” He recalls that the band’s label sent copies of the LP to Bob Dylan and Neil Young, prompting the latter to write back that he thought it was great.

Despite its apparent influence, Pink Flag didn’t chart in the U.K. Although Chairs Missing made it into the Top 50 the following year and 1979’s 154 would go into the Top 40, an act of music-industry politics stymied the band’s progress. After the release of Chairs Missing’s “Outdoor Miner” single, the record company was caught attempting to help it along illegally, doing something akin to payola, and the song subsequently plummeted on the charts. Lewis still harbours resentment over the matter and thinks about an alternate universe where Wire went on to play Top of the Pops.

In reality, Wire broke up in 1980. They put out the posthumous live release Document and Eyewitness in 1981, which Rollins likens to the Stooges’ Metallic K.O. because of the audience’s hostility. In the meantime, Newman began a solo career, with 1980’s A–Z, while Gilbert and Lewis worked together as Dome, Cupol and, with Mute founder Daniel Miller, as Duet Emmo.

The band regrouped in 1985 and the next year they issued the Snakedrill EP, which contained a rattling, gothy number with a disco beat called “Drill” – five years later, they’d put out The Drill, an album of remixes of that song, and in 2013, they’d name their curated, roaming festival Drill. In the meantime, they put out a dancey, New Wave–inflected full-length, The Ideal Copy, and decided they were finally ready to do a proper tour of the U.S. The thing is, though, that they didn’t want to play any of their older material.

Wire in 1985. “The idea was that if we played older songs, it would slow us down,” Graham Lewis says.

“The difference between the Seventies and the Eighties, sonically, was massive,” Newman says. “In the Seventies, there was a lot of distortion. By the mid-Eighties, everything in Europe was clean.”

“The idea was that if we played older songs, it would slow us down,” Lewis says. “Our manager at the time told us that if we were going to do that, we’d spend nearly all of the time explaining why we weren’t doing older stuff. So we went to New York and did press to explain it. One of the last interviews we did was with Jim DeRogatis, who has since become something of a legend in his own right. When the interview was done, he told us he had a band called the Ex-Lion Tamers that played Pink Flag. And I was like, ‘Oh, really.’ Bruce and I had been joking about how brilliant it would be if we had a cover band that played the first three albums, so I told him and our manager about it. It turned out Jim and his bandmates wanted to see America so they took their vacations and did the whole tour. Every night, we played [Modern Lovers’] ‘Roadrunner’ with them as an act of solidarity. It was just a great accident.”

The band continued to explore electronic sounds throughout the Eighties, notably refiguring some of their own songs for 1989’s synthy IBTABA, which contained their last minor hit in the U.K., “Eardrum Buzz.” By the early Nineties, drummer Gotobed grew wary of the experimentation and left the group, prompting them to rebrand themselves “Wir” for 1991’s keyboard-centric The First Letter. They broke up again the next year, after which Lewis worked on electro-acoustic music in Sweden, Gilbert drew inspiration from noise music in Japan and Newman worked on his solo music.

Wire re-formed in full in 1999 and toured in 2000, playing sets that relied heavily on their first three albums, defying themselves. “We had an uneasy relationship with the older material then, but we didn’t have any other material,” Lewis says. “So we went through everything and found songs we could do serviceable versions of.” In recent years, however, they’ve modernised their set lists once again. “Once you’ve played it live, it’s on YouTube,” he says. “Once that started to happen, it would have been ridiculous to go about things in the same way we had been before.”

“We’ve somehow trained the audience to accept, more or less, anything we do,” Newman says. “It’s a remarkable and quite funny thing that Wire doesn’t have a particular style. If you compare our records over the years, they’re quite different but somehow they all sound like Wire.”

The band put out its first album of new music in over a decade, Send, in 2003, and a year later Gilbert quit the group. Lewis chalks that decision up to Gilbert not wanting to perform live or fly, as well as “tension between people.” Gilbert, in interviews, has never explained why he left the group. Nevertheless, the band decided it didn’t want to repeat what it had done with its name when Gotobed left: “You don’t want to be too predictable,” Lewis says with a laugh. “But I had sorted that one out because when we were Wir, I said if somebody else leaves, we’ll call the band Wi [pronounced ‘we’]. And if somebody else leaves, it’ll just be called I.” He laughs.

Wire have since carried on, eventually drafting It Hugs Back guitarist Matthew Simms, all the while trying out new sonic experiments. On 2010’s Red Barked Tree, Newman challenged himself to write songs on an acoustic guitar in short bursts. For 2013’s Change Becomes Us, they revisited songs they’d abandoned from 1979 and 1980, leaning heavily on their repertoire from their live album Document and Eyewitness, recorded during those years.

Their latest, Silver/Lead – for which Lewis would send Newman text, so Newman could arrive at the studio with finished songs – has been in the works for some time. The group paced its recording sessions so that the LP would be pressed and ready to go for its 40th anniversary. “There’s a don’t-look-back aspect to Wire,” Newman says. “Wire is always about what we’re doing now, what we’re doing next. And an anniversary could easily be an excuse for wallowing in our own past, but instead putting out a new album and launching it with a Drill Festival in L.A., instead of playing in a basement in Covent Garden, where we started. We’ve had this plan for about five years.

“With Wire, we approach things as if we were a band in our twenties or thirties, and we do albums quite often,” he continues. “We tour as regularly as we can, and we don’t get offered those great festival headliners because we’re not playing the classical albums. We might not be playing huge venues, but we make it work. I’ve never had a day job. I think figuring out how to survive as a creative person in his world is quite an important thing to do.”

“I think figuring out how to survive as a creative person in his world is quite an important thing to do,” Newman says.

Part of the group’s will has been the creation of its Drill festivals, which it has hosted all over Europe and North America. They’ve allowed the group to play alongside the likes of Swans, Savages, St. Vincent and others, as well as “The Pinkflag Guitar Orchestra.” “We did the first Drill in London for the release of Change Becomes Us because we needed to do something to launch the album,” Newman says. ” I thought, ‘Wire doesn’t do that many festivals, and, anyway, what is a festival?’ I just thought we could do our own.”

The L.A. Drill, which is launching Silver/Lead, notably features a solo electric performance by longtime Wire fan Bob Mould and Fitted – an ensemble featuring Wire’s Lewis and Simms with drummer Bob Lee and super-fan Mike Watt that’s named after a lyric from the 154 track “Map Ref. 41°N 93°W.”

“I was just thinking about who I would like to see in L.A., so I sent Mike [Watt] a Facebook message saying, ‘Hey, Matt and I were wondering if you’d like to play with a drummer of your choice,” Lewis says. “Honestly, within minutes I got a reply.”

“Folks are going to see Watt trying this best to play for the first time with one of his heroes in front of people,” Watt says. “Luckily, [Graham] asked me to pick the drummer, and Bob Lee is on board to help me hopefully not get too freaked out. I am most honoured to be invited to such a thing.”

The band already has three more Drill festivals announced for 2017, in the U.K., Germany and Belgium. “It’s great fun,” Lewis says. “Over the course of three days, you actually get to meet people, rather than getting shoved in one end of the sausage machine, and off you go to the next festival.”

Wire’s Drill festivals are perfectly tailored to their status as punk’s ultimate cult band. For Newman, it’s the right level of success. “I think one of the wisest things Madonna said on the subject of fame is, ‘Be careful what you wish for,'” he says. “I don’t think I would like to be so famous as not to be able to walk down the street. I think that would be depressing. Some people think we’re really good, but obviously not everybody does. And maybe it’s good to have that context. You wouldn’t make something unless you thought you were good at it. You have to have a certain level of arrogance to do this kind of work.”