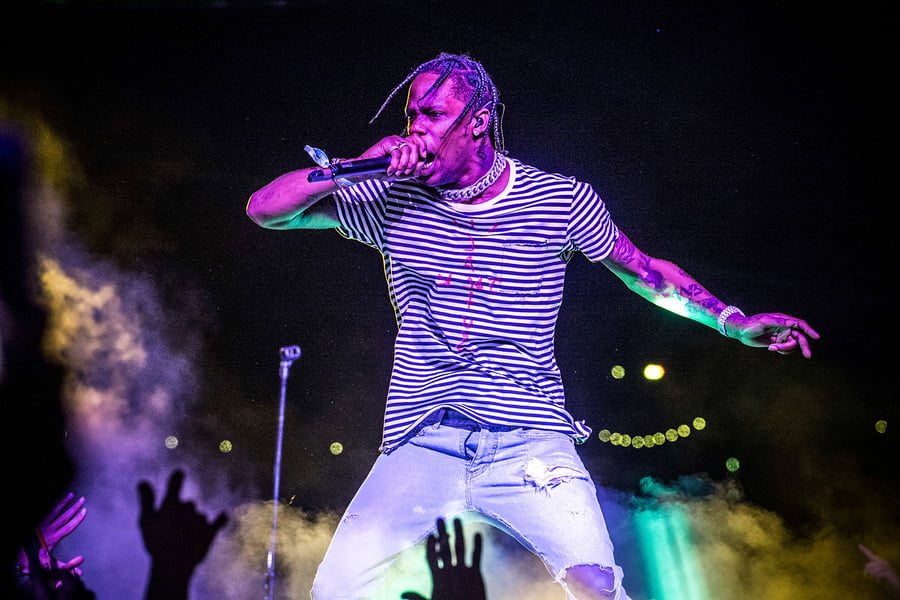

The eight deaths and dozens of injuries at the Nov. 5 Astroworld Festival in Houston’s NRG Park appear to have been preceded by a series of red flags, going back to the early days of festival founder Travis Scott’s touring career. In 2017, Scott, always known for wild shows, went further than usual, encouraging a fan to jump from a second-floor balcony at Terminal 5 — and during the same performance, another fan, Kyle Green, 27, was pushed off the third-floor balcony, ending up paralyzed. “I see you, but are you gonna do it?” Scott said to the fan on the second floor.

Even before that, Scott repeatedly urged concert crowds to overwhelm security and join him onstage. “There are more of you than them,” he told the crowd at 2015’s Summer Jam concert in East Rutherford, N.J. That same summer, Chicago police arrested him after he urged fans to climb over barricades to go onstage at Lollapalooza.

At 2019’s second Astroworld Festival, a mass of hundreds of fans overwhelmed metal barricades as they rushed into the event, sending three people to the hospital with minor leg injuries from trampling. At the time of the incident, Houston police reportedly wrote on Twitter that the festival didn’t have enough staff, and that “promoters did not plan sufficiently for the large crowds,” before deleting the tweet.

Another warning sign came much closer to the tragedy, at 2 p.m. on Nov. 5, when fans stampeded by the dozens through a V.I.P. security entrance at Astroworld, knocking over metal detectors, as captured on video by a local news reporter. “It suggests they weren’t prepared for the kind of crowd they were going to get,” says a concert insurance expert, who asked for anonymity because of his connections to Astroworld’s organizers.

NRG Park itself had just experienced what could have been a cue to beef up security: Outside the very same venue on the night of Oct. 24, less than two weeks before Astroworld, young fans of Playboi Carti also reportedly knocked over metal detectors and moved metal barriers outside the venue before the concert — which organizers canceled due to the chaos.

Many other big festivals take extensive measures to prevent gate-crashing: At Chicago’s Lollapalooza, the insurance expert points out, organizers arrange each year for an elaborate system of barriers — “what we like to call the Welcome to the Thunderdome barricade system, all around Grant Park.” Fans who break through one set of gates find they’ve only made it to another gate.

The expert also questions why Astroworld organizers weren’t monitoring social media to pre-empt what seemed to be organized gate-crashing. But Jim Digby, co-founder and president of the concert-industry nonprofit Event Safety Alliance, recommends caution before blaming organizers. “That sounds to me like an out-of-control audience,” he says, “not an unprepared promoter.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Paul Wertheimer, a concert-safety expert who’s been crusading for safer shows and festivals since 1979, when 11 concert-goers were crushed to death outside the doors of a Who show, says “it was obvious to everybody that the crowds were going to be difficult, because everybody has been so cooped up. And young people want to get on with their lives and have fun and have some camaraderie. Everybody knew that. But the industry didn’t prepare for it.”

The gate-crashing also meant that the Astroworld crowd could have swelled significantly beyond the 50,000 tickets sold for the event. “Overcrowding and crowd-crashing is the original sin of planners of live events,” says Wertheimer. The first Astroworld in 2018 reportedly drew about 40,000 fans, while crowd estimates for 2019 were also 50,000. In general, festival organizers have been pressured financially, the insurance expert says, by increasing demands for “huge guarantees” from artists and their agents: “They really gouge them.”

So in order to make a profit, promoters have to either raise ticket prices, which can only go so high before discouraging attendees, “or have to charge less and push the capacity envelope,” the insurance expert says. (Digby argues that festivals are not getting more crowded, and that the expert’s scenario “is a generalization… probably not as well researched as it needs to be.”)

“Frankly,” the expert adds, “capacity should probably be determined by some sort of government entity.” In Houston, at least, there is no official capacity limit for outdoor events, Fire Department Chief Samuel Peña told reporters on Saturday.

It’s too early to assess how the tragedy at Astroworld will affect the concert industry going forward, but at the very least, the insurance expert predicts, it will make it much harder to get insurance for festivals — and in particular, fairly or not, rap festivals. “I’m so frightened of that notion,” he says. “I don’t even want to speculate how difficult it’s going to be. Especially for a hip-hop festival. I’m not not excited about what we’re gonna have to go through to get it done. It’s gonna be tough.”

“And nothing like this has ever happened at Lolla, [Austin City Limits], Gov Ball — any of the big festivals that have those crowd sizes, you’ve never heard of anything like this happening. What made this so different? What happened here?”

Wertheimer thinks he knows one possibility. “This could be another classic case… where the safety people signed off on something they knew or should have known could be extraordinarily, extremely unsafe, especially with Travis Scott, who had a history of chaotic, chaotic events.”

For Wertheimer, there’s only one way to change the way the concert industry does business: “Start criminally charging these promoters and agencies that sign off on these reckless events,” he says. “Do that, and safety will change overnight. If nobody’s criminally charged, families of the deceased will sue; those injured will sue. And four years from now, they’ll settle with everybody. We’ll do the legal dance, and then in between and after, it will be business as usual.”

Steve Adelman, vice president and lead counsel for the Event Safety Alliance, says it’s way too soon to cast blame. “There is the instinct to rush to judgment before we know what actually happened,” he says, while urging a look at audience members’ conduct as well. “Another thing that we don’t know is: What crowd behavior either contributed to the injuries and deaths, or was the product of other things that were either poorly determined in advance or poorly implemented last night?”

Digby says the concert industry “can’t afford any more blows. We’re an industry on the edge as it is right now. Covid has decimated our industry. And it’s decimated a good portion of our workforce… This kind of a blow is painful in so many ways, not just the lives that were lost. But we’re sad for Travis Scott, and we’re sad for our industry that we now have to go through another moment where we’re raked over the coals, and more possible setbacks for our long-delayed future.”

From Rolling Stone US