Round here they call him Jimmy. The artist known to the world as Vance Joy has been eating BLTs at this modest café on the main drag of Ashburton in Melbourne’s leafy, well-heeled southeast since his mum was doing the ordering.

This afternoon though, when the ukulele comes out for a playful tinkle, the manager nearly drops his cameroons in the rush to turn down Dark Side of the Moon and whip out his camera. “Sweet sounds of #riptide,” reads the Instagram caption within the hour.

It’s a hashtag with serious pedigree. APRA’s Song of the Year. Number one in Triple J’s Hottest 100. Sixteen million YouTube views. Top 10 in Britain and half a dozen European countries, and the golden ticket to a five-album deal with Atlantic Records in New York.

“It is a little frightening,” says the man born James Keogh 26 years ago. “It’s such a bizarre lottery. When I wrote that song, I knew people liked it, but for me it was just one of a group of five songs that I still believe are really good.

“It’s definitely got flavour,” he concedes, playing down the prizewinning entrée in the context of last year’s introductory EP, God Loves You When You’re Dancing. “It’s like a spicy dish. Not every one you make is going to be that flavoursome. They’ll all have their good points but they’re going to be different meals.”

Considering the heat, Keogh’s a decidedly cool hand in the kitchen. He does admit to feeling “a bit freaked out” twice on his rocket ride from here to there. First was on the return flight from New York after playing for Atlantic execs in late 2012. The other was when he lost his voice for three months last summer, in the midst of recording his debut album, Dream Your Life Away.

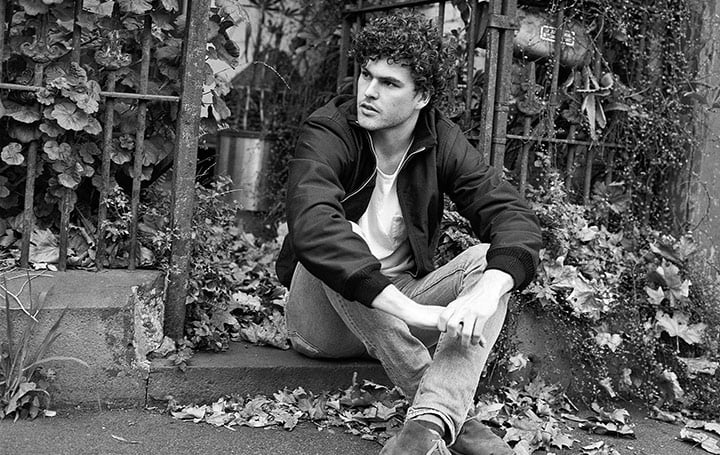

But the general projection from between the tight curls, bottomless brown eyes and easy smirk is about as calm and sensible as a boy next door can be. Maybe it’s the folksy familiarity of his immediate surrounds. He still kicks back at his family home between tours, a short stroll down the road in the old bedroom that spawned most of the album’s songs.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“The other night I was up late with hay fever and I was kind of delirious,” he recalls with a grin. “I grabbed the guitar, put the doona over the top of my head so it’s quieter, then my sister comes in and she’s like, ‘What are you doing? What is wrong with you?'”

This cosy domestic cocoon provides the overwhelming atmosphere of the album, albeit with a worldly depth imbued by producer Ryan Hadlock (Gossip, the Strokes) at Seattle’s Bear Creek Studios. From the bedside table and backyard vista of the first track, “Winds of Change”, to the lone strum of “My Kind of Man”, it’s a record that bottles the wide-eyed rush of the teen dreamer with all due heartache and falsetto.

Keogh is pleased to hear this. It is Mum or Dad, or both, who tend to hear his songs first. “You have to be careful. You don’t want to play favourites. They both want to hear the new stuff. It depends what time of night you walk into their room,” he says. “But you get a real response. My sister doesn’t necessarily tell me what I want to hear.”

The man who would be Vance traces his creative journey with the same prosaic detail he applies to describing his daily train trip from here to St Kevin’s Catholic boys’ school in Toorak. The $500 guitar-and-amp starter pack his dad bought him at 14. The “really average” songs he’d play “to lukewarm responses” from mates at the footy club.

The turning point as a songwriter was “Winds of Change”, he says. It gave him a good feeling, like “music might be a viable plan” to usurp his half-hearted law studies. After an erratic series of open mic nights at various suburban Melbourne pubs, he remembers one gig where strangers suddenly outnumbered family and friends and he thought, “maybe this is legit”.

“Riptide” was the product of a single day of recording at Chris Cheney’s Red Door Studios, a converted church in Collingwood that Keogh looked up on Facebook, at the end of 2010. “That was a weird thing,” he muses. “It felt really special, going in without anything, doing three vocal takes and there it is. My voice doesn’t really sound like it did then. When I listen to it now, I’m quite detached from it. It feels like some weird, lightning-in-a-bottle moment.”

It’s fair to say some critics have tended to agree, as Keogh’s low-key stage persona struggles to meet the epic swell of “Riptide”, but the singer remains unflappable. In fact, it’s with something like delight that he pores over excerpts from several unflattering gig reviews from recent months. “Ah, I like that!” he hoots. “‘Likeable’? That’s nice. ‘Adequate’? Good. ‘Anonymous’? Hmm. ‘Cute’, that’s good. ‘Bland’, no. ‘Unspectacular’? Well, spectacular is pretty big, so I’ll cop unspectacular. I mean, seriously,” he concludes cheerfully, “you write what you write. And you do what you do.”

With the big U.S. push looming, he’s similarly dismissive of the more hyperbolic language that’s recently entered his vocabulary. He catches himself explaining the reappearance of “Riptide” among the newer songs on Dream Your Life Away as a case of “capitalising on momentum”, then realises it’s a term “business people” have taught him. “Fuck momentum,” he says, almost irritated for a moment. “It doesn’t figure into what I do.”

Indeed, it must be infinitely more attractive for a songwriter to let his imagination soar above and beyond the freakish swell of that one song and picture the possibility of that fifth Vance Joy album floating free of expectation, maybe 10 or 15 years further off towards the horizon.

“I hope it sounds awesome and really different,” Keogh says. “I like the idea of changing, transforming. Obviously I think the essence of the songs will remain. I wanna write good songs,” he says, emphasising both words with a finger on the café table.

“I guess every songwriter wants to be some fully realised amazing artist, like Peter Gabriel. He writes some wacky shit but it’s got its mass appeal. Something like that. And really good film clips. Really bizarre stuff. I think people react to that. You don’t wanna be appealing to the lowest common denominator.”

Then again, everybody loves the boy next door.

“Mmm.” He sounds dubious. “I don’t know. Let’s see what happens. Maybe it’s good that it’s like that. If that’s my look, maybe I can maintain that and be free creatively. I just wanna have one big, strong presence. I guess it’s just about owning it. And having a really strong will.”

This article features in our latest issue (#755, October 2014). Available now.