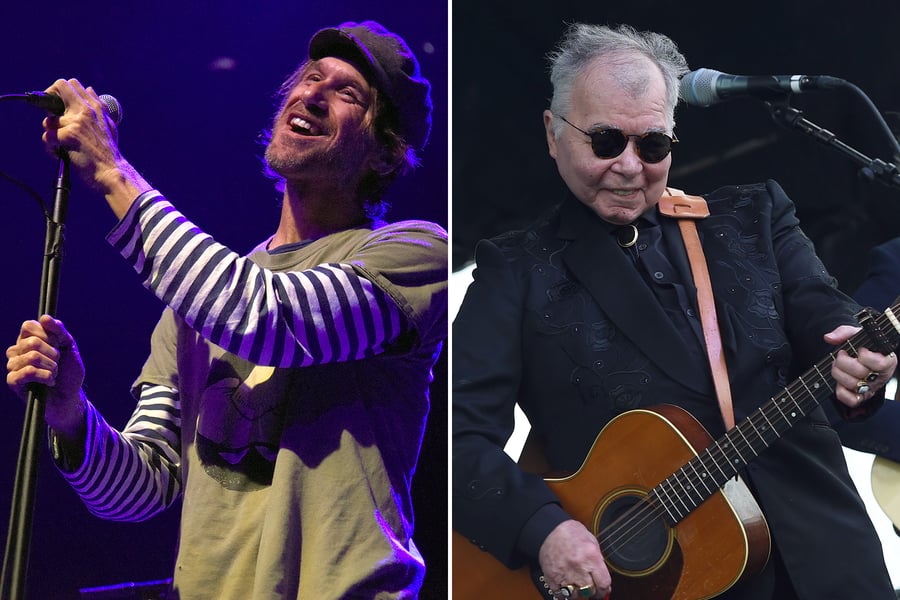

In the 24 hours since John Prine died of complications from COVID-19 on Tuesday, countless musicians and artists have paid tribute to the Nashville legend. Here, singer-songwriter Todd Snider remembers his hero, mentor, and friend.

The first time I heard about John Prine, I was about 19 and I was playing an open mic, and this guy named Kent Finlay, who was my mentor, told me, “You’re like John Prine.” I didn’t know who he was, so I just went home and devoured his music. It became something I obsessed over. I was like, “Goddamn, this guy speaks to me. This is who I want to be. How can I get a coat like that?” I was like, “I’m going to be like John Prine.” A few years later, I realized that’s like saying you’re going to be like the guy in your neighborhood that got hit by lightning.

This morning, I was trying to write a little poem about John. I was writing about the first time I met him, in Memphis, in the late Eighties. He was making The Missing Years. When I think of John, that’s still the person I see. He was staying at the Peabody Hotel, and I was hired to pick him up. I met him at his hotel room and he was sitting there listening to Merle Haggard. It was in the morning and he had a cig going and a little vodka going. I told him, “I’m supposed to take you over to the studio.” The first thing the two of us realized was that his birthday was the day before mine. And then he said, “I’m starting my own label,” and I said, “I’m going to be on it.” And we laughed. And then eight fucking years later, I was.

Anyways, I gave John cigarettes and drove him around, and then he found out that I sang. The next day, I was playing a show at the Daily Planet and John came. When I was done and everyone had left, it was just me, John, Keith Sykes and this guy Kenny, who owned the place, and they had my guitar. I said, “Would you play one?” And John said sure. He took the guitar and said to Keith, “I got this one that I thought we could try tomorrow.” And then he played “All the Motherfucking Best.” I just was shaking. I couldn’t believe I knew him.

Another time, I got to go to his house, and it was me and John and Townes and Guy and Keith. John had that Christmas tree. [Prine used to keep a Christmas tree up at his home year-round.] John played “Chain of Sorrow” and I asked him how he came up with that song, and he just said, “It happened.” He explained to me the first time he witnessed a massive tragedy and he didn’t understand how he felt, and then a girl with black hair broke his heart, and he was like, “Oh, I remember this. This is how I felt when that boy got killed.”

A few years after that, John and I went on tour in Europe. We took a 10-hour flight, got off the plane, and as soon as we get in the car and the driver starts going a certain way, John says, “You’re going the wrong way.” And then we proceed for an hour and a half, and John hardly looked up from his paper when the driver said, “Aw fuck, you were right.” John was like, “It’s OK. You’re OK.” And he meant it. I always thought, in that moment, that that’s why he’s John Prine. That moment was as close as I ever came to thinking I ever saw insight into the songwriter in him.

One of my favorite songs of his was “Fish and Whistle.” I’ve always thought of that as a gospel song. What a moving thing to say, “You forgive us and we’ll forgive you, and then we’ll go fishing.” I had never ever considered the idea of forgiving God until I heard that song.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Another line that always gets me is in “Come Back to Us Barbara Lewis Hare Krishna Beauregard”: “She said, ‘Carl take all the money’/She called everybody Carl.” What the fuck is that about? I’ve always carried that line forever.

I could never totally calm down when John was around. He knew that, and he didn’t hold it against me. We were never backslapping buddies. I was always like, “You need some more soda, sir?” I always felt, why talk when you can just listen to that guy? Him and Willie Nelson are the most revered people in the history of the backstage. In the rumors that go around in our little world, there’s no weird ones about those two. There’s no, “And then he flipped over the table and said, ‘Fuck all of you.’” Just about everybody else has one of those rumors.

It had been a few months since I’ve seen John. One of the last times I saw him, the two of us played a show in my hometown in Portland. That meant a lot to me. I got to show him my favorite pizza place. Him and Fiona loved it, I knew they would. That made my whole tour.

John had been fighting. He had just beat cancer. I always worried about him before this. But he was playing such amazing shows, and you could tell he wanted to play. One of the last times we sang together at the Ryman last year, he grabbed my hand afterward and he looked at me, and he said, “I love you, Todd.”

The music business I got into was basically Johnny Cash’s world, and it’s always been the most loving place. John was the dad of it, until yesterday. He was a Hank Williams, Johnny Cash-level person here in Nashville. It’s just weird to think of the world without him in it, without him walking in it. When I first heard his song “When I Get to Heaven” a few years ago, I cried. It was so beautiful. But it also scared me. I think he knew it was going to be the last song on the last record.

Nobody’s ever deserved there to be a heaven more than John Prine. And if there’s not a heaven, they oughta get one together pretty quick, because John’s coming.