Roger Daltrey takes the collapse of the old-school music business personally. When the Who reunited in the mid-Nineties after a brief sabbatical, Daltrey promised his doctor that he and his band would help him raise awareness (and money) for the fight against teen cancer, something that’s proven hard to do in the digital age.

“After the Who got back together, we did a couple of shows and gave all the money from the live album to the charity,” Daltrey says. “There was a record market and also a DVD market, so we gave quite a bit of money out of that. There used to be a music business. It wasn’t owned by some rip-off organization that pays musicians peanuts.”

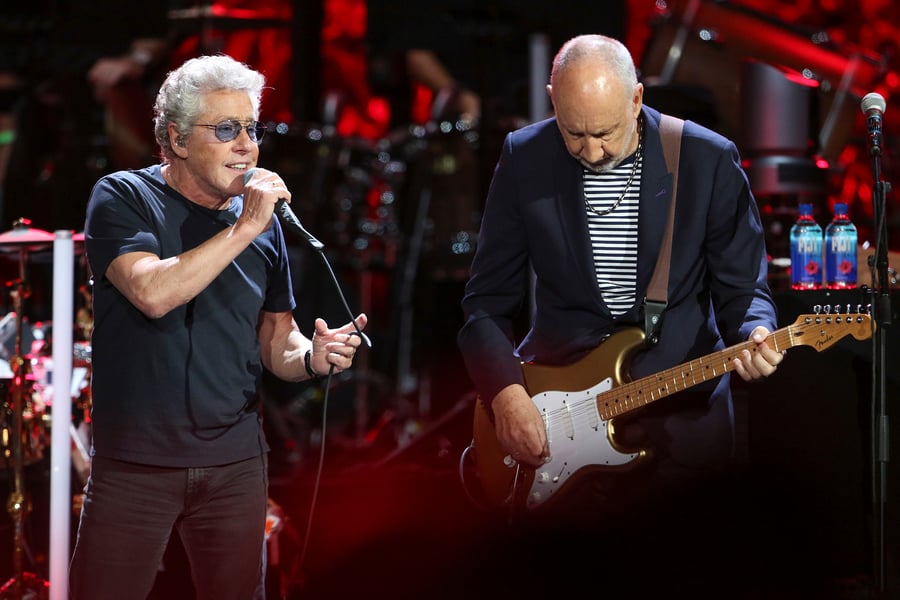

Daltrey faced two challenges at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic: One, the Who was forced to cancel the remainder of its 2020 shows. Two, which means the band was unable to raise the money they intended to earmark for Teen Cancer America — a foundation Daltrey started with Pete Townshend in 2012 to help teen cancer patients by way of building cancer units in hospitals — and the Teen Cancer Trust in the U.K.

Undeterred, however, the band has found a new way to give back: The Real Me, a podcast hosted by Daltrey that features teen cancer patients not only talking about their stories but presenting songs they’ve written and performed. It premieres on October 5th across all platforms. (The Who song of the same name was also licensed as the podcast’s theme song.)

And, as Daltrey tells RS, the Who are plotting a return to live performance next year, which will include several benefits to make up for lost funding.

You’ve been involved with raising awareness and funds for teen cancer research by way of concerts for years now. How hard has the pandemic slammed those plans?

The music business is just getting back on its feet, which is great. But the charity side of it, like Teen Cancer America, for instance, it’s extremely difficult. All our fundraising is based on events. So we lost probably $10 to $12 million last year for the Teenage Cancer Trust in the U.K. In America, we lost out on two of the big events I’ve been staging for the last 10 years, partly to support an autism program and mostly for teen cancer. We’ve lost out probably to the tune of $8 million there.

How has that impacted the organization’s plans?

It has curtailed our expansion. In eight years, we had reached 43 hospitals with programs. And in some of the biggest institutions in America — Sloan Kettering in New York, Stanford, UCLA. If we’d gone on like we were going, that number would have been 60. We haven’t cut back on our services in the hospitals. But we’re still at 43. We’re doing an awful lot online, which is helping, but it’s not the same. Online stuff is all right, but it’s not human contact.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

How did you first become aware of the teen cancer cause?

The Teenage Cancer Trust in England was started by my GP and we supported him from day one. It’s such a simple thing to understand. I remember my teenage years. I was bullied very early on when I was 12, 13. Some of it’s quite painful stuff. And I thought, “Just imagine what it would have been like if someone had told you I had cancer at that age.” Young children get cancer but don’t know the ramifications of what they’ve got. Whereas a teenager, unfortunately, knows everything. They know exactly the journey they’re going to be on. The mental strain of that must be horrendous.

Was anyone in your family afflicted with cancer?

Sadly, my younger sister Carol, who was 32 at time, died of breast cancer, so I saw cancer. That was in the Eighties. That’s life and it’s sad. The horror of it never leaves you, more than the mental anguish.

You’ve held benefits with the likes of the Foo Fighters, Pink, and Eddie Vedder. How do you get people to participate?

I used to say to the musicians, “Without the support of this age group, we’ve got no industry at all.” And even today, you’ve got no life support unless you’ve got that age group supporting you. This is a great way of giving back to them.

Tell me about your new podcast, The Real Me, featuring musical performers by teen cancer patients.

It was an idea our CEO came up with. We have access to musicians and studios, and it’s a great way for [the patients] to talk about how they feel going through this. Some of this stuff is really interesting to listen to. I was flicking through a few yesterday, some really great singers there. Just to listen to them expressing themselves, you’re drawing something out of them, and that’s got to be good. If that wasn’t coming out in that way, it would be all bottled up inside. Obviously, their words are painful. But their voices are quite extraordinary. There’s one country song I was listening to yesterday, a good country voice, too.

Next month you’re finally returning to live shows, playing some solo gigs in the U.K.

Yeah, I’m exploring my back catalog. I’ll obviously do Who songs, but with a different kind of instrumentation. I’ve got to sing between now and when the Who are next going out, which is the end of next March and April. If I don’t sing between now and then, I don’t know whether I will be able to do it then. I’ve always promised myself and my audience that I would never want to go out there and be a mediocre singer.

How deep into your solo catalog are you going? Some of those Leo Sayer songs from early on?

Yeah, because when I come back to, as I call it, my hobby — which is my solo career — it’s a variety of music, right up to the last album, which was old soul songs. I haven’t got a clue what the show going to be like. But the one thing it will not be is boring.

What about “Avenging Annie”?

Eventually, I’m going try “Avenging Annie,” but I’m going to have to lower the key. That’s a song ahead of its time, a real women’s liberation song, that one. I’m not promising to do it every night, but, you know, I might do it once. This is the kind of show where I won’t know what it is until the day we do it. But the looser the better. What I’ve learned in my time is that of all the great shows we’ve done, the ones people remember most are the ones you fuck up.

This year, of course, is the 50th anniversary of Who’s Next, and there were rumors that the band might celebrate by playing the album live on stage.

The problem in the business at the moment is a structural one. We can’t get any venues, because there’s a huge blockage to people waiting to get venues because so many people had to cancel tours. So the earliest we can get in is next March.

And will you consider doing a Who’s Next set in your show?

No, I don’t see the point. Who’s Next is a great album, but it’s best left as a great album. Just playing albums live doesn’t do anything for me, personally. The show we’ve got with the orchestra is fantastic, and the Who’s catalog has so much varied stuff that makes it better than just listening to Who’s Next. Why do that? Go and play the record and get stoned or whatever you wish and have a good time! That’s a way to celebrate. You don’t need us to do that.

And what about a possible Who’s Next box set?

I don’t really know. That’s record company business. They own the catalog. I feel like a painter who’s finished a painting. I never want to see the bloody thing again! I’m sorry, but you’ve got to let this stuff go.

Will you help raise more funds for teen cancer with the Who shows?

We’re hoping to do the Albert Hall in March for the Teenage Cancer Trust. And we are hoping to do a show we’ve done in Los Angeles, which is very exclusive. It’s not really a fan’s one, but it makes an awful lot of money. There are a thousand tickets and we play in someone’s garden and we’ll raise upwards of $4.5 or $5 million. We’re hoping to do that next year as well.

Earlier this year, Pete even said he had some new songs prepped for a possible new Who album.

[Laughs]

Is this news to you?

Certainly is. I’ve just fallen off the chair! But there’s a song on the last album we did, which I think is a fabulous album called Who. It’s called “Beads on One String.” And the opening line is, “Don’t you ever say never/It don’t mean a thing.”

From Rolling Stone US