The skinny boy with the thick dark hair sat in the back row of a full classroom, head down, intense brown eyes fixed on his notebook. As his teacher lectured, the boy scribbled with his pencil, as if taking down every word. But George Harrison wasn’t listening. The 13-year-old son of a bus driver drifted into visions of his future, filling his notebooks with obsessive drawings of guitars — the instrument he’d been longing to play since he’d heard Elvis Presley’s hits, the sonic embodiment of all the fun and joy missing from dreary postwar Liverpool. Soon enough, he was filling his notebooks with lyrics and chord charts, and maybe an occasional sketch of a motorcycle.

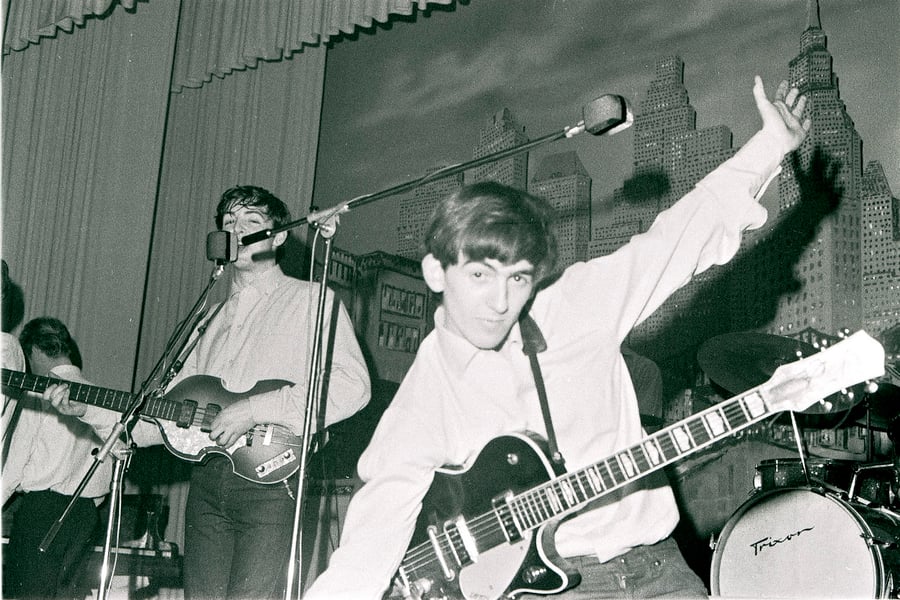

He became close friends with an older classmate, Paul McCartney, who needed a guitar player for a new band. “I know this guy,” McCartney told the group’s leader, John Lennon. “He’s a bit young, but he’s good.” Harrison passed his audition, playing the guitar instrumental “Raunchy” on the top half of a double-decker bus one night — and with that, he was a Beatle, or at least a Quarryman. But his bandmates never quite shook their idea of him as a junior partner — an “economy-class Beatle,” in Harrison’s sardonic formulation — and he soon began pushing for an upgrade.

Harrison wasn’t really the quiet Beatle. “He never shut up,” said his friend Tom Petty. “He was the best hang you could imagine.” He was the most stubborn Beatle, the least showbizzy, even less in thrall to the band’s myth than Lennon. He was fond of repeating a phrase he attributed to Mahatma Gandhi — “Create and preserve the image of your choice” — which is odd, because his choice seemed to be no image at all. He was an escape artist, forever evading labels and expectations. Harrison challenged Lennon and McCartney’s songwriting primacy; almost single-handedly introduced the West to the rest of the world’s music through his friendship with Ravi Shankar; became the first person to make rock & roll a vehicle for both unabashed spiritual expression and, with the Concert for Bangladesh, large-scale philanthropy; had the most Hollywood success of any Beatle, producing movies including Monty Python’s Life of Brian; and belied a rep as a solitary recluse by putting together the Traveling Wilburys, a band that was as much social club as supergroup.

As Martin Scorsese’s new documentary and accompanying book make clear, Harrison had no casual pursuits. He followed his interests in the ukulele, in car racing, in gardening, and especially in meditation and Eastern religion with fierce energy. “George had a really curious mind, and when he got into something he wanted to know everything,” says his widow, Olivia Harrison, who met him in 1974 and married him four years later. “He had a crazy side, too. He liked to have fun, you know.” Harrison’s first wife, Pattie Boyd, described him veering between periods of intense meditation and heavy partying, with no middle ground. “He would meditate for hour after hour,” she wrote in her memoir, Wonderful Tonight. “Then, as if the pleasures of the flesh were too hard to resist, he would stop meditating, snort coke, have fun, flirting and partying…. There was no normality in that either.”

Says Olivia, “George didn’t see black and white, up and down as different things. He didn’t compartmentalize his moods or his life. People think, oh, he was really this or that, or really extreme. But those extremes are all within one circle. And he could be very, very quiet or he could be very, very loud. I mean, once he got going, that was it. He wasn’t, you know, a wimp. I’ll tell you that. He could outlast anyone.”

Harrison and his bandmates lost local talent shows repeatedly in the beginning, but that didn’t shake them. “We were just cocky,” Harrison said. Things turned around rather sharply, and Harrison loved it all at first, embracing the stages of success in “sort of a teenage way”: his underage apprenticeship in Hamburg’s red-light district (where he lost his virginity while his bandmates pretended to sleep in the same room — they applauded at the end); the painstaking process of developing his own country-and-R&B-inflected guitar style; the beginnings of Beatlemania; the fame, the money, the girls, the tight bond among the Fabs. “We were four relatively sane people in the middle of the madness,” Harrison said. In the early years, he also idolized Lennon in particular: “He told me he really, really admired John,” says Petty. “He probably wanted John’s acceptance pretty bad, you know?”

But in 1965, Harrison dropped acid, and all at once, he didn’t believe in Beatles. “It didn’t take long before he realized, ‘This isn’t it,’ ” says Olivia. “He realized, ‘This is not going to sustain me. It’s not going to do it for me.’ “

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“It’s all well and good being popular and being in demand, but, you know, it’s ridiculous,” Harrison told Rolling Stone in 1987. “I realized this is serious stuff, this is my life being affected by all these people shouting.” He felt physically unsafe. “With what was going on, with presidents getting assassinated, the whole magnitude of our fame made me nervous.”

On the set of A Hard Day’s Night, he met Boyd, a lithe blond model; on the set of the Beatles’ next movie, Help!, he encountered Indian classical music — which led him on a quest that would last far longer than the marriage. Trying to master the sitar led him to yoga, which led him to meditation, which led him to the Eastern spirituality that would help define his life. “He was searching for something much higher, much deeper,” said Shankar, the sitar virtuoso who became Harrison’s mentor and friend. “It does seem like he already had some Indian background in him. Otherwise, it’s hard to explain how he got so attracted to a particular type of life and philosophy, even religion. It seems very strange, really. Unless you believe in reincarnation.”

For a while, it was like he was sitting in the back of the Beatles’ classroom, doodling sitars — hence “Within You Without You,” that beautiful, anomalous Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band track. But after he realized he’d never be more than an average sitar player, he refocused on the guitar and songwriting, coming up with some of the Beatles’ best songs: “Something,” “Here Comes the Sun,” “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” not to mention “Not Guilty” and “All Things Must Pass,” which Lennon and McCartney wrongheadedly rejected. He also began playing slide guitar, developing an emotive, distinctive instrumental voice that reflected his newly liberated spirit.

Fighting for his place in the band, and his songs’ place on its albums, was exhausting. So was just being a Beatle. “Sometimes I felt a thousand years old,” said Harrison — who was 27 when the Beatles ended. “It was aging me…. It was a question of either stop or end up dead.” The band’s touring days were over, but Beatlemania had left him with something like post-traumatic stress disorder. “If you had 2 million people screaming at you, I think it would take a long time to stop hearing that in your head,” says Olivia. “George was not suited to it.”

Harrison became friends with Bob Dylan (“They had a soul connection,” Olivia says) and Eric Clapton, and his time with the two solo artists showed him a way forward. As the Beatles imploded in 1970, he stepped up with the triple album All Things Must Pass, letting loose his storehouse of songs.

The next year, at Shankar’s request, Harrison persuaded Clapton, Dylan and Ringo Starr, among others, to assemble for the Concert for Bangladesh, which set the template for every all-star rock benefit of the next 40 years. The concert was a triumph, but the aftermath was a painful mess, as Harrison’s efforts to get the proceeds to refugees bumped against tax codes and bureaucracies.

His marriage was also collapsing: Infamously, Boyd left him for Clapton, though the two men’s friendship somehow survived. For all of his spiritual grounding, Harrison was drinking too much, partying too hard, sleeping around. “Senses never gratified/Only swelling like a tide/That could drown me in the material world,” he sang, wearily, on the title track of his next album, Living in the Material World.

Harrison’s 1974 North American tour was his last time on the road, save for a short 1991 Japan jaunt. With lengthy Shankar sets, strained Harrison vocals and his refusal to play familiar Beatles songs (he’d shout his way through halfhearted versions of “Something”), reviews were brutal. Harrison was unnerved by the rowdy crowds and his hard-partying backup band — it didn’t feel like his world anymore. “George talked a lot about his nervous system, that he just didn’t want to hear loud noise anymore,” says Olivia, who began dating him the year of the tour. “He didn’t want to be startled. He didn’t want to be stressed.”

Harrison released seven more solo albums, but he became progressively less interested in any conventional career arc. “George wasn’t seeking a career,” says Petty. “He didn’t really have a manager or an agent. He was doing what he wanted. I don’t think he valued rock stardom at all.”

His relationship with Olivia centered him, and he eased back on the partying. Harrison was ecstatic when the couple had their only child, Dhani, in 1978. “The only things he felt I had to do in my life are be happy and meditate,” says Dhani, who grew up in Friar Park — the 120-room mansion in the English countryside Harrison purchased in 1970, straining even a Beatles finances. The property was beautiful and mysterious, with caves, gargoyles, waterfalls and stained glass installed by Sir Frank Crisp, an eccentric millionaire who’d owned it until his death in 1919. Harrison was intent on restoring the 35-acre property’s gardens, which had fallen into disrepair. As a small boy, Dhani says, “I was pretty sure he was just a gardener” — a reasonable conclusion, since Harrison would work 12-hour days out there, missing family dinners as he pursued his vision, planting trees and flowers. “Being a gardener and not hanging out with anyone and just being home, that was pretty rock & roll, you know?” says Dhani, who understood his father’s affinity: “When you’re in a really beautiful garden, it reminds you constantly of God.”

After a five-year gap between albums, Harrison enlisted producer Jeff Lynne for 1987’s Cloud Nine, which won him a Number One hit with “Got My Mind Set on You,” a rollicking cover of a Sixties obscurity. More important, a session to record a B side — a casual collaboration with Lynne, Dylan, Petty and Roy Orbison — led him to the Traveling Wilburys, the post-Beatles project he most enjoyed.

He reveled in being in a band again, not to mention collaborating with Dylan, who was both friend and hero. “I’m so much more comfortable being a team player,” Dylan would tell Petty. The Wilburys recorded two albums (Dhani remembers hanging with Jakob Dylan and playing Duck Hunt on his Nintendo while the band worked on the second one downstairs), but never managed a live show.

“Every time George had a joint and a few beers, he would start talking about touring,” says Petty. “I think once or twice we even had serious talks about it, but nobody would really commit to it.” A third Wilburys album was always a possibility. “We never thought we were gonna run out of time,” says Petty.

Instead, after a 13-date tour of Japan with Clapton, Harrison became a gardener again. “He didn’t want to have any obligations,” says Olivia. He kept writing and recording songs in his home studio, but turned down offers to appear on award shows, or to do almost anything. “I’ve just let go of all of that,” he said. “I don’t care about records, about films, about being on television or all that stuff.”

In 1997, he was diagnosed with throat cancer, and underwent radiation treatment. Two years later, a mentally deranged man somehow made his way into Friar Park, and in a horrific, prolonged tussle, stabbed Harrison through a lung before Olivia subdued him. Harrison made a full recovery, but Dhani believes the injuries weakened his father as he subsequently battled lung cancer. The disease spread to his brain, and after a long fight, George Harrison died on November 29th, 2001. Olivia is convinced that the hospital room filled with a glowing light as his soul left his body.

“He would say, ‘Look, we’re not these bodies, let’s not get hung up on that,’ ” says Petty, who has practiced meditation ever since his friend introduced him to it. “George would say, ‘I just want to prepare myself so I go the right way, and go to the right place.’ ” He pauses, and laughs. “I’m sure he’s got that worked out.”

This summer, Dhani Harrison, now 33, returned to Friar Park and gazed out at the garden for a long while. It had never looked better — the trees his father planted have finally grown. “He’s probably laughing at me,” says Dhani, “saying, ‘That’s what it’s supposed to look like.’ You don’t build a garden for yourself, right now — you build a garden for future generations. My father definitely had a long view.”

Editor’s note: This story was originally published in September 2011.

From Rolling Stone US