“There’s very few rock & roll bands,” Malcolm Young explained to a Dutch TV interviewer around the time of AC/DC‘s 2000 album Stiff Upper Lip. “There’s rock bands, there’s sort of metal bands, there’s whatever, but there’s no rock & roll bands – there’s the Stones and us,” he chuckled. When asked by the interviewer to explain the difference between rock bands and rock & roll bands, he replied, “Rock bands don’t really swing … a lot of rock is stiff. They don’t understand the feel, the movement, you know, the jungle of it all.”

Few rock & rollers have ever understood “the jungle of it all” like Malcolm Young, and fewer still have ever been as single-mindedly devoted to its perpetuation. From 1973, when he formed AC/DC with his younger brother Angus, to 2014, when dementia and other health issues forced his premature retirement, Malcolm never once allowed the band to deviate from its swinging, swaggering, riff-driven course. During Malcolm’s tenure, AC/DC’s recordings featured three different lead vocalists, three different bassists and five different drummers; and yet, the band’s musical aesthetic remained so stubbornly consistent as to make the Ramones look like flighty trend-jumpers by comparison.

AC/DC never mucked about with drum machines or synthesizers, never worked with “hit doctors,” never invited guest stars to appear on their records, and never made musically touristic forays beyond the Chuck Berry riffs and Australian bar circuit that originally spawned them – their idea of musical experimentation was to let Bon Scott take a bagpipes solo on “It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock ‘n’ Roll),” or affix a tolling church bell to the start of “Hell’s Bells.” The most “pop” song in their catalog is “You Shook Me All Night Long,” a fist-punching paean to marathon fucking, and the closest they ever came to recording a ballad was “The Jack,” a nasty six-minute slow blues about contracting gonorrhoea. “Rock and roll is just rock & roll,” Brian Johnson sagely opined in “Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution” – and by the same token, AC/DC has always been just AC/DC, doggedly mining the same vein for good-time gold.

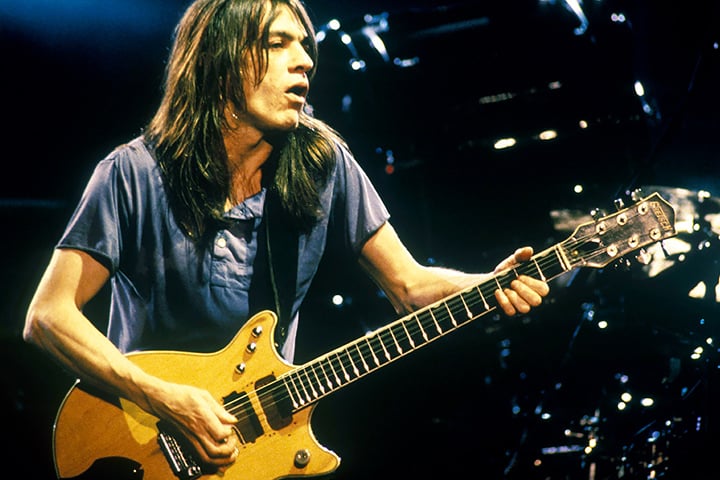

But if AC/DC’s public image was largely defined by Angus’s naughty schoolboy, Bon’s lascivious pirate and Brian’s lusty bricklayer personas, it was Malcom who truly defined the band’s lean ‘n’ mean sound. In addition to serving as the captain of the good ship AC/DC, he was also its chief architect and mechanic, tinkering with riffs and songs as tirelessly as he tinkered with his 1963 Gretsch Jet Firebird, which underwent countless modifications as he strove to unleash the ultimate guitar tone. “He’s the engine in the Mack truck that is AC/DC,” Anthrax’s Scott Ian told Loudwire in 2014. “He’s the driving force behind that band; has been since Day One. To the casual listener, they probably don’t know who Malcolm Young is … but Malcom’s the guy. He’s the greatest rhythm guitar player ever.”

Indeed, while notable guitarists like Ian, James Hetfield and Dave Mustaine have regularly sung his praises – no less an authority than Eddie Van Halen has called him “the heart and soul of AC/DC” – the general public has remained largely oblivious to his importance to the band. (As a budding hard rock fan picking up 1979’s Highway to Hell for the first time, it was all about Angus and Bon for me; I wouldn’t realize until years later that the tiny guy on the album’s cover with the tight T-shirt, centre-parted hair and thuggishly menacing gaze was actually the one responsible for so many of the clarion guitar riffs that attracted me to the record in the first place.) Such relative anonymity was perfectly fine with Malcolm, who was usually happy to let Angus, Bon or Brian handle band interviews. In concert, he rarely strayed more than a few feet from his Marshall stack, concentrating on keeping the riff machine stoked while his younger brother’s duck-walking, pants-dropping, guitar-shredding antics stole the limelight.

But Malcolm was far more than just a riff-meister. “From the get-go, Mal’s always been one to come up with melody ideas,” Angus explained to me in 2005, when I interviewed him for a Revolver feature about the making of 1980’s epochal Back in Black. “I’m a bit rough and raucous – I go for the rhythmic things – but Malcolm will dial in a melody, and likes to get it so it’s all hooking together and feels right.”

Malcolm had clearly internalised the lessons he’d learned at the knee of older brother George Young, who’d taken on a similarly low-key role as guitarist, songwriter and producer with legendary 1960s Australian hitmakers the Easybeats, and who – in partnership with Easybeats guitarist Harry Vanda – had already become a successful producer of other acts by the time Malcolm and Angus formed AC/DC. (George, who along with Vanda produced such classic early AC/DC albums as TNT, Powerage and Let There Be Rock, died on October 22nd at the age of 70.) Like George, Malcolm was never content with just a gut-punching riff, a swinging groove and a catchy chorus; everything had to be primed for maximum sonic impact, as well.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“Mal always had a better ear for recording and mixing than I did,” Angus told me. “He was more involved with that when we were younger, fiddling around with sounds and stuff. He tunes into it more than me; I’m more about just picking up the thing and play it. He helped me a lot with dialing in sounds from my amp; I would be saying, ‘I can’t get nothin’ out of this Marshall,’ and he would help me sort it out and get the best out of it.”

It was also Malcolm who kept AC/DC firmly focused during the traumatic weeks following Scott’s unexpected death-by-misadventure in February 1980. While the band’s management and record company pressured them to find a new singer, Malcolm was adamant that he and Angus direct their energies into finishing the songs that would eventually become the Back in Black album. “There were a lot of suggestions [about auditioning singers],” Angus told me, “But Malcolm kept saying to me, ‘We’ll do it when we feel we’ve got all our music together. The rest of it can wait!’ We didn’t want to be rushed into anything.”

While Malcolm’s death at the too-young age of 64 is certainly a massive blow for AC/DC fans everywhere, it’s unlikely that he would want Angus to bring it all to an end on his account. Even in his absence, AC/DC has continued to function like a finely-tuned clockwork mechanism – the band successfully soldiered following his retirement, recording and touring behind 2014’s Rock or Bust with nephew Stevie Young taking over for his uncle on rhythm guitar. That the band continues to thrive without Malcolm isn’t a reflection on his lack of importance to it, but rather a testament to the enduring brilliance of the material he wrote, and the perfection of the musical machine that he designed to deliver it. So long as there’s enough electricity left in the world for some guitarist somewhere to hit a ringing, window-rattling A chord, Malcolm Young’s spirit will live on. Rock in Peace, Mal.