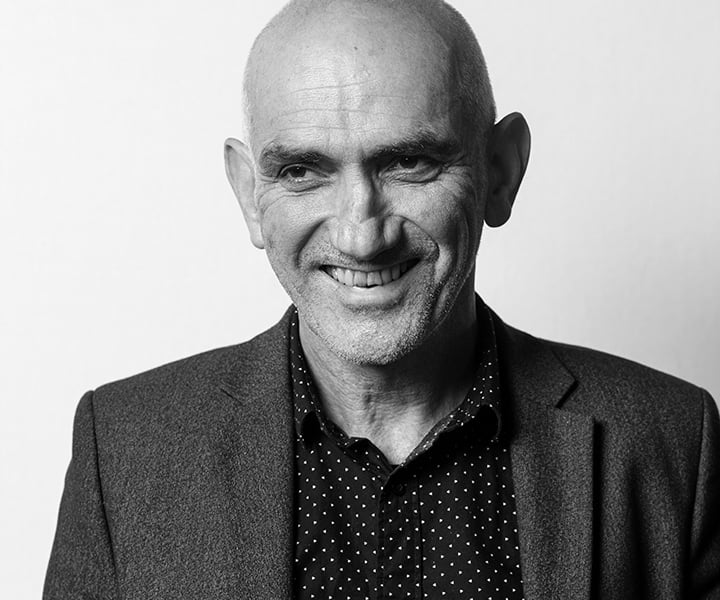

A slight, bald, wiry figure in jeans and an Elefant Traks hoodie unlocks the gate to the weatherboard cottage in St Kilda that he’s called home for 25 years. He offers a firm, warm hand and a grin that makes light of the fact that he is, against all odds, Paul Kelly. “Really, I’m not that conscious of any expectations,” says the man who might, outside of the sports arena, be our most universally revered public figure. “I still hold my heroes in my head. Al Green. Curtis Mayfield. Sam Cooke. Leonard Cohen. Bob Dylan. Hank Williams. That’s the measuring stick, for me.”

As part of our ongoing Living Legend interview series, Rolling Stone spoke to Kelly about his legacy, songwriting process and new album Life Is Fine.

What stories did you love as a kid?

I mostly remember family stories, like my dad being sent to the shop at the age of five to get a pound of butter. He’s walking home and he has a little bit to eat. It tasted good, so he had a bit more. Halfway home he realised he was gonna get in trouble so he ate the rest to destroy the evidence. His parents said, “Did you get the butter?” He said, “No, they didn’t have any.” Then he threw up.

Describe your first songwriting attempt.

The first one I wrote when I was 21. I wrote it in open G tuning. It had two chords and four lines and it was pretty Van Morrison-ish. I can still sing it, roughly: “It’s the riding of trains that takes you/It’s the going down that wakes you/It’s falling apart that makes you/It’s… something else that breaks you.” It’s not a terrible song. Worse followed.

Who are the critics in your head? Can you name them?

I don’t have a particular judge and jury up there. Playing songs to the band can be a way of feeling out whether a song is good. They’ll always do the best by a song, but you pick up which ones they really like. The inner critic is not that reliable. You like a song one day and you don’t like it the next.

Did you always have a sense of music as a force for social justice?

I came up listening to a lot of folk music so those historical events songs were always there. And I do have a natural bent for telling a story, so when I hear a good one… some just demand to be written. But the demand is not “I have to right the injustices of the world”. With “Maralinga” for instance, it was all about the imagery. I remember reading about the big black mist [from the British nuclear tests in South Australia] rolling and roiling along the ground towards them. “From Big Things Little Things Grow” started with the image of Gough Whitlam pouring sand into the hands of Vincent Lingiari. So those potent images sort of tell me to write. It’s more of an aesthetic drive, rather than “I need to set the record straight”.

For a couple of decades the image of Paul Kelly was of a fairly shy, reluctant public figure.

That’s pretty accurate, yeah. I don’t like talking about myself much. I’m happy singing. I find talking a bit harder. I think I’ve got better at it.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

But then you laid yourself bare with your book How To Make Gravy and the Stories of Me documentary. Did they comprise a watershed for you?

Maybe they did. The memoir happened by accident. I was thinking of ways to write notes to this A to Z set of recordings and I stumbled on a method, which was to take the lyrics of the song as the starting point to write about anything I wanted. But once I realised it was going to be a memoir, I knew I had to be frank because I believe a memoir that holds things back is a failed book. I had to stay true to the genre.

Culturally you’re one of Australia’s most unifying figures. Is that important to you?

That’s all accidental. It’s not something I seek. A lot of my favourite performers are polarising. I don’t try to be all things to all people. I couldn’t think of anything worse.

It would make you a really good candidate for something. Have you been pressured in that direction?

I’ve never been approached for public office. I get approached to do various causes but I don’t do much. The rest of my family are much more politically active and vocal and full of more conviction than I have. I’ll stick with Yeats: “The best lack all conviction and the worst are full of passionate intensity”.

In the last decade you’ve performed Yeats, Shakespeare, the Merri Soul revue, funeral songs… have you deliberately distanced yourself from pop?

It wasn’t conscious. Pop songs are my métier; they’re what I like to write but they’re hard and they take me time. Other things catch my attention. I wish I could write more pop songs. I’m pleased to have this new record where I’ve got… well, they’re my version of pop songs. They’re punchy, they’re short, they have riffs, they’re upbeat.

Life Is Fine sounds like an old-school Paul Kelly record, from the Eighties or Nineties. Was that as easy as it sounds?

No, I’ve just been slowly plugging away until I had enough. You write songs and you put them aside like odd socks in different drawers and finally you find a few that seem to match. When you’ve got four or five songs that start talking to each other, then you can get a vision of the record and, “Oh, I’ll try and write a few more like that.”

Give us your best songwriting trick.

You can’t compose unless you improvise. After being in the room for a few days with the band, playing music, I usually come home and something pops out. So just go and play.

—

Main photograph, credit: Matt Coyte.

From issue #790, available now.