A tall, bald Australian singer sits next to a skinny, young English producer in a studio in Shepherd’s Bush, London. It’s October 1982, the rest of the band has flown home after five weeks of intense recording, and the two of them are doing the final mix of a new album. As the opening song, “Outside World”, comes to a close and bleeds into the opening blast of the next one, “Only The Strong”, the singer bounces in his seat and waves his hands around.

“Wait until the kids in Mullumbimby hear this,” he says.

The producer has no idea where Mullumbimby is, so the singer paints a picture of northern New South Wales for him and then tells him about Australian surf culture, complete with panel vans and station wagons with music blasting out of them as kids wax up their boards.

“What do you think they’ll make of the new songs?” asks the producer.

“They’ll be in shock,” says the singer. “But they’ll recover.”

They finish the mix at 5am, grab a few hours sleep, master it at nine in the morning, then the singer tucks the acetates under his arm, strides out, grabs a taxi to Heathrow and flies back to Australia. A couple of months later, it’s not just the kids in Mullumbimby who are in shock.

The album that Midnight Oil fans refer to as 10 to 1 became their first to break into the Top 10 (it went to Number Three), the first to achieve a million global sales and the album that finally put them on the world stage. But the story of its creation and its legacy is a surprising one. They went into the studio uncertain of their future, with a make-or-break attitude and an openness to change. They came out with a politically outspoken and sonically adventurous record that would make their name, set their course and also come back to dog the singer when he decided to enter federal politics, with opponents quoting back his lyrics and accusing him of selling out his former ideals.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

It’s the album that changed everything.

10,9,8,7,6,5,4,3,2,1 artwork.

Exactly 30 years later, three men walk into a studio at ABC Radio National in Sydney. It’s not hard to pick which one is the politician. That would be the bald-headed, 193-centimetre tall bloke in the blue suit. Peter Garrett is not here today to make any announcements pertaining to his job as Federal Minister for School Education, Early Childhood and Youth. He’s here with two old friends, drummer Rob Hirst (black T-shirt, still as enthusiastic as a Labrador puppy) and guitarist Jim Moginie (wide-brimmed hat, still as laconic as a drover), to go back in time and piece together the making of 10,9,8,7,6,5,4,3,2,1.

When was the last time they all saw each other?

“When was the last major catastrophe?” Hirst responds, to laughter all round. The band officially broke up in 2002, but regrouped to play at WaveAid in 2005 (for victims of the Boxing Day tsunami) and Sound Relief in 2009 (for victims of the Victorian bushfire disaster).

To understand the genesis of 10 to 1, you first have to look at the aftermath of its predecessor, Place Without a Postcard, which hadn’t become the great leap forward they’d hoped for after recording it in England in 1981 with Glyn Johns, the veteran producer who had worked with the Who, the Faces and Eric Clapton.

“I think the band was somewhat collectively disappointed with Postcard,” says Hirst, casting a glance at Garrett and Moginie. “Not because of what was recorded and not because of Glyn Johns, who could be prickly and a bit of a fractious character, but he was a thrill to work with and he was a hero to all of us in different ways. We thought the album would be our big break.”

It wasn’t, and they found out early. The senior vice president of their overseas record label listened to Postcard and bluntly told the band that they should immediately return to the studio and try to record some singles. Although the album may not have captured the power of an Oils live show, it did contain what would turn out to be enduring songs such as “Don’t Wanna Be the One”, “Armistice Day” and “Lucky Country”. The band was disappointed and dispirited.

“Our capacity as a live band had reached a point where we were very confident we could walk into any room and smash the roof off,” says Garrett. “Yet this hadn’t translated on that record. Sometimes something like that can pull a band apart. It had the opposite effect on us.”

“I think the band was collectively disappointed with ‘Postcard’. We thought the album would be our big break.”

They flew to England in mid-1982, where manager Gary Morris set up a weekly residency at The Zig Zag Club, a small venue in west London. There the band roared through their back catalogue and started honing some of the new songs they were writing. Each week the show became sharper, tighter and more intense, not that you would have known it from the typically parochial English music press.

“We used to go to London just to get the bad reviews,” says Hirst. “You couldn’t take it personally. Every Australian band was slagged. The English journalists couldn’t wait. They had their stock standard abuse for Australian bands and trotted out the same lines every time.”

At the same time they were working on new material in a rehearsal room in Islington. At one point, German metal guitarist Michael Schenker was shredding at ear-splitting volume in the room to one side of them while Ian Dury and the Blockheads were churning out their twisted punk-funk on the other. They were also living in reduced circumstances. In 1981, they resided in upmarket South Kensington and then on Johns’s estate in rural Sussex during recording. Now they were surviving on takeaway curries. Garrett doesn’t recall going out much at night, but Moginie says he was constantly seeking out live music, from seeing Nureyev at the ballet to hearing Rip Rig + Panic and the Birthday Party. He was particularly influenced by seeing post-punk pioneers Gang of Four, buying the same guitar amp as Andy Gill to achieve a similarly cutting sound.

Early versions of “US Forces”, “Read About It”, “Only the Strong” and “Short Memory” had already taken shape. But the Oils could always come up with the songs. What they needed was someone who could take their undisputed power and passion onstage and somehow translate that onto record. They’d gone for experience and reputation with Glyn Johns. This time they went in the opposite direction, choosing a 21-year-old rookie whose past work had very little to do with the Oils’ style of music.

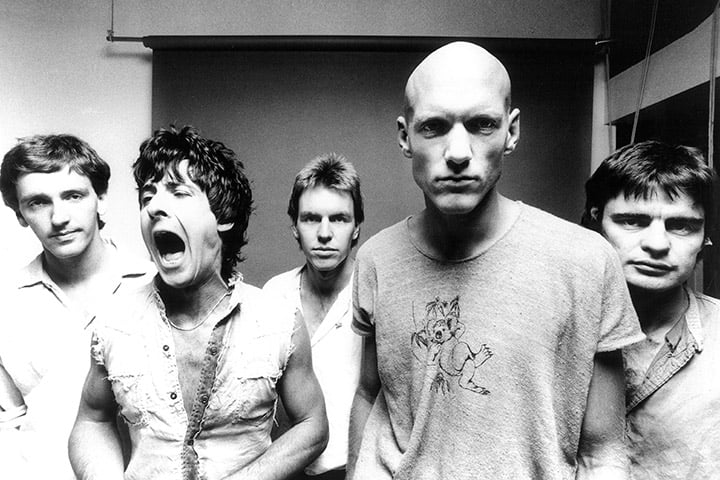

Midnight Oil live in 1982.

Nick Launay had the strangest of introductions to record production. One of his earliest jobs at the age of 18 in the late Seventies was editing pop hits down to around two-and-a-half minutes so the K-Tel label could cram 20 of them onto their vinyl compilation albums.

In 1980 he took a job as assistant engineer at the Town House studios in Shepherd’s Bush, where he learned the ropes from producers Hugh Padgham and Steve Lilly-white, and worked on albums including Public Image Limited’s The Flowers Of Romance, XTC’s Black Sea, and Kate Bush’s The Dreaming, and post-punk singles such as the Birthday Party’s “Release the Bats”, Gang of Four’s “To Hell With Poverty!” and Killing Joke’s “Follow the Leaders”.

His connection with Midnight Oil came about as a result of his old K-Tel gig. One night in 1979, after spending the day whittling down songs, he took the synth-pop song “Pop Muzik” by M and did the opposite: he extended it. Robin Scott, the English musician behind the M moniker, loved the result, and Launay’s mix was released as a 12-inch single. Scott was later managed by Nadya Anderson, an Australian expat who had worked at Melbourne community radio station RRR as a presenter and producer. Scott introduced her to Launay and the two hit it off – she became his manager, his girlfriend and later his wife. Anderson had been a longtime champion of Midnight Oil at RRR, and introduced her new boyfriend to their music, along with many other Australian bands.

Meanwhile, Hugh Padgham was one of the people approached about possibly producing the band’s next album in 1982. He was too busy to take the job, but recommended Launay. The band went around to where he was living with his mother in Fulham and they sat in his bedroom, which was dominated by fluorescent green carpet and massive speakers. Launay played them some of the records he’d worked on, at high volume.

“I remember he played us ‘Release the Bats’,” recalls Hirst. “I thought, ‘Fuck! Why don’t we get some of that?'”

Still, both sides were cautious. They came from totally different worlds – the Oils from the pub rock scene of Sydney; Launay from the post-punk scene of London. Launay had listened to Place Without a Postcard and even though he quite liked the songs, he felt that it was a little too old-school rock for his tastes. Then he went to see them at The Zig Zag Club.

“I was still a little unsure, but they came on and they were just incredible,” says Launay from his home in L.A. “They were mind-blowingly tight and the energy in Rob’s drumming and the way the two guitars worked off each other was amazing. And Peter was just on fire. I really liked AC/DC. But this was like intelligent AC/DC, plus elements that reminded me of the Clash. They had this punk side to them that I hadn’t realised from hearing their records.”

London, 1981 (l-r): Peter Gifford, Jim Moginie, Peter Garrett, Martin Rotsey, Rob Hirst.

They agreed to work together and in September entered studio two at the Town House. It was the first band that Launay had been independently contracted to produce. The band lived upstairs in what Garrett describes as “a muso backpackers”. Van Morrison was recording songs for Inarticulate Speech of the Heart next door. Moginie remembers having breakfast one morning in the studio canteen downstairs when a sprightly older gent sat down nearby – it took him a few moments to realise it was Cliff Richard.

The band wanted a shake-up and that’s exactly what Launay gave them. He took away all Hirst’s cymbals, as they were recording drums in the high-ceilinged, stone-walled room that produced the gigantic drum sound of Peter Gabriel’s third album and XTC’s Black Sea. Cymbals would wash everything out, so Hirst had to hit pads instead, and his cymbals were all overdubbed later. Launay also suggested Hirst use the newly introduced electronic LinnDrum for the pulsing beat underneath “Power and the Passion”.

Did Hirst know anything about LinnDrums at that point?

“I knew that I hated them,” he says, laughing. “In those days there was that whole thing of drummers being replaced by machines, so I looked askance at this thing and thought, ‘You want my job.’ But Nick was right and it worked for that song.”

“Nick had no fear,” says Moginie. “He’d try anything to see what would happen. There were no rules. He would always have a razor blade out, doing zig-zag cuts on two-inch tape and splicing bits together.”

For “Only the Strong”, Launay got Hirst to play take after take, some completely straight, others with his trademark wild drum fills, then he “Frankensteined” them together. “I spent a whole day editing all the best bits with razor blades and sticky tape, but in the end that song to me captures what I saw live, where Midnight Oil is this powerful steamroller of a machine.”

The intense drum solo from “Power and the Passion” came from somewhere else. It was done in one take.

“Personally, I was having a mini nervous breakdown around this time,” admits Hirst. “I was frustrated about what had happened with the band in the previous 12 months and I wasn’t really enjoying being in London. I felt a long way from family and friends. I would run around Ravenscourt Park in the rain every day to try to get my head straight. Then I’d go into the studio and take it out on the kit. When I listen to 10 to 1 I hear this person who is frustrated and unhappy and he’s trying to let it out. When Pete screams at the end of ‘Somebody’s Trying To Tell Me Something’, that’s a real scream. Everyone was feeling it, I think.”

There were glum faces all round the morning after they finished the basic tracks for “US Forces”. They realised too late that it was in the wrong key for Garrett’s voice. Everything had to be redone apart from the guitars at the end – Launay loved them so much that he decided to use a pitch-changer to shift them. Many of the sounds on the album which many people assume were electronically generated, were in fact the result of everything from re-pitching guitars to playing piano strings with drumsticks. That smashing sound at the end of the “Power and the Passion” drum solo is not a sound effect, but Hirst dropping a big light globe from the top of a ladder onto the floor.

“When I listen to the album now I also hear the lyrical concerns of when it was made,” says Moginie. “The Cold War; paranoia; only the strong survive; who’s running the world; something’s going on here and we want to talk about it. I think that struck a chord with people.”

Indeed, it’s a remarkably outspoken bunch of songs, even for a band that never was backward in coming forward about their beliefs. It’s something that has come back to haunt Garrett now that he’s a minister in the Labor federal government. “US Forces” strongly denounces American military intervention in foreign affairs, with strident lines such as “US forces give the nod/it’s a setback for your country” and “Politicians party line don’t cross that floor”. How can he stand by that song when he is part of a government that supports the US-Australian alliance and the joint defence facility at Pine Gap, and last year announced that 2500 US troops would be based in Darwin?

“Very easily,” says Garrett. “I was more than happy to sing ‘US Forces’ the last time we were on stage together and I was a member of the government then. Great song, great lyrics. It’s a song of its time. It was about what we as a country were facing in terms of the stand-off between the United States and the Soviet Union. It’s hard to put yourself back in that place now and remember how the Cold War atmosphere was such a big concern and how potentially dangerous it was. That is the essence of the song.

“If you want to extrapolate that song to today, you can, and people are entitled to do that, but they’re missing the point of the song. Today I think it’s much harder to be definitive about where our national interests are best served vis-à-vis our relationship with the United States or China or the Middle East.

“The other thing I’d say is that I think people have a very simplistic view about politics when they’re not inside it. The fact of the matter is that when you decide to enter politics you do become a team player and that’s what I am.”

Moginie and Hirst have been quiet during Garrett’s answer. There’s a small silence afterwards. I wonder if they’re thinking what I’m thinking – that despite Garrett’s eloquence and the fact that we all know he has to work within the machine of the Labor party, there appears to be some self-justification and back-pedalling to suit his current position. Then Hirst speaks.

“Well I’m not a team player and neither is Jim, so here’s what I think,” he says, to slightly nervous laughter from Garrett. “When I see 2500 troops stationed in Darwin, that prickliness and irritation I feel is real. Our diggers would never have allowed that. They fought for our sovereignty. I’m amazed that it went through without more public comment and debate. We have this closeness to America, which I see as the fading empire, and we have a failure to get with it and recognise China as the empire of this century. I know Pete disagrees with me on this.”

Things aren’t exactly awkward in the room. Voices aren’t raised and there doesn’t appear to be any ill-feeling. In fact, you get the sense that this kind of disagreement isn’t totally new. I suggest that it sounds like the caucus of ex-Midnight Oil members is a place where a lot of what is diplomatically called “robust discussion” still takes place.

“Yeah, look, I’m pretty hawkish on China, so Rob and I would have a disagreement on that even if we were still in Midnight Oil and I wasn’t in politics,” says Garrett. “And getting back to ‘US Forces’, it’s construed as an anti-American song but it was an anti-Reagan, anti-Republican song about what they were doing and the impact it was having on our country at the time.”

So you could quite comfortably get up onstage with Midnight Oil tonight and sing “US Forces”?

“Yes, of course. There are no songs that are off limits. They’re songs. They’re not acts of Parliament.”

Moginie still hasn’t expressed an opinion. Where does he stand on any of this?

“I’m the emollient in the group,” he says, to laughter from the others.

“You’re the essential oil!” Hirst chuckles.

“They disagree and I get my own way,” says Moginie.

Did Midnight Oil have these big ideological arguments when they were still together?

“We agreed on all the important stuff,” says Moginie. “That’s the main thing.”

One thing everyone who was in that studio 30 years ago can agree on is the legacy of 10 to 1. Music writers Toby Creswell, John O’Donnell and Craig Mathieson placed it at number 23 in their 2010 book 100 Best Australian Albums (Diesel and Dust topped the list), while Triple J listeners last year voted it at Number 21 on the Hottest 100 Australian Albums Of All Time (Diesel was number 33). For the producer and the band, it’s not the polls and the critics’ opinions that matter as much as the place the album has in their hearts and minds.

For Launay, it led to working with many other Australian acts at turning points in their careers, including INXS’s The Swing, The Church’s Séance and Models’ The Pleasure of Your Company. He’s also enjoyed long-running partnerships with both Silverchair and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds and worked with Midnight Oil twice more, on 1984’s Red Sails in the Sunset and 1993’s Earth and Sun and Moon. Where does he place 10 to 1 in his long and varied CV?

“It’s right up at the top. It flows from beginning to end and sonically it’s as good as anything I’ve ever done. I’d only really just started making records then, yet I was allowed to go crazy plugging this into that and experimenting with the sound. I listen to it now and think, ‘God, how did that happen?’ It’s a very special record made in a very special time. But the greatest thing to come out of 10 to 1 is that the people in that band are my best friends to this day.”

As for the band, they’re all aware that five years later Diesel and Dust was the mega-seller that shifted over five million copies, yet the significance of 10 to 1 is something that still moves them.

“There’s no question it was a pivotal album and a turning point,” says Garrett. “10 to 1 gave us many more opportunities as a band and a lot more people heard us and rethought who we were. Before that I think a lot of people just saw us as a bunch of guys from the northern beaches of Sydney with this tall guy jumping up and down at the front.”

“Some people find it too abrasive,” says Hirst. “I remember Marty from the Church coming up to me and saying, ‘Rob, do you really like that drum sound?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah! I love it!’ It wasn’t for everyone, but when you listen to bands that came later like Tool and Rage Against the Machine, they’re intelligent bands that make very hard, abrasive music, not unlike the Oils of 10 to 1 in many ways. It’s incredible to me that an album made 30 years ago still kind of takes your breath away.”

“I think if you love the Oils, then you love 10 to 1,” says Moginie. “There’s something about the sound of it that doesn’t sound like any other bands from that time. The dynamics of it are mercurial and curly. Diesel is a very clear record and it sounded good on the radio, but 10 to 1 was wilder. It was more…”

He pauses for a moment to try to find the right word. Then it comes to him.

“It was more us.”

—

From issue #733 (December 2012).