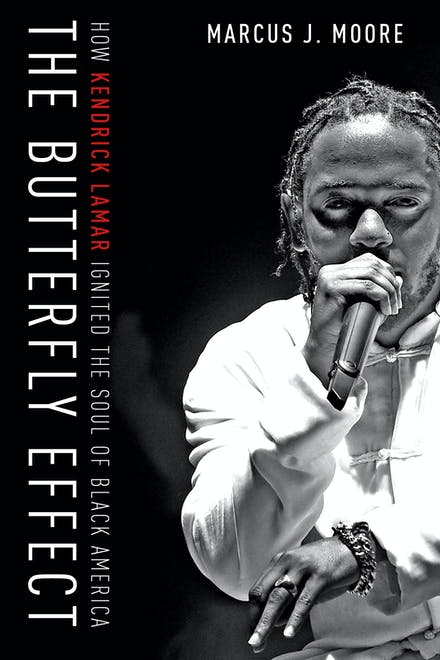

Marcus J. Moore delves deep into the influence of Kendrick Lamar in his new book, The Butterfly Effect: How Kendrick Lamar Ignited the Soul of Black America. An award-winning author who has written for The New York Times, Pitchfork, Entertainment Weekly, The Washington Post, NPR, and Rolling Stone, just to name a few, Moore – like the rest of the world – has seen the rapper go from an aspiring wordsmith on the streets of Compton to one of the most successful and critically-acclaimed artists in the genre.

Close to ten years on from the release of his debut album, Lamar has turned his passion for greatness into far-reaching mainstream success, with sales closing in on 18 million albums, 12 Grammy Awards from 29 nominations, and the distinction of being the first non-classical or jazz artist to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music.

Moore’s new book, which arrives today, takes an in-depth look at the chart-topping hip-hop icon, tracing his history from his days as an introverted kid in Los Angeles, to his distinction as the “poet laureate of hip-hop“. Throughout its pages, Moore goes deeper than just providing the story of Lamar’s growth, but contextualises it, showcasing how the artist’s moral complexity, political understanding, wit, empathy, musical depth, and breadth have combined to turn him into one of the few MCs who can unite those from all ends of the hip-hop spectrum, along with those who harbour barely a passing interest in the genre.

In this excerpt, Moore paints the picture of Lamar’s origins, providing readers with a background of the Compton backdrop against which a hip-hop legend was born, pairing it with the political and cultural upheaval experienced therein, and setting the scene for what gave rise to one of music’s most successful careers.

Before Kendrick Lamar was a world-renowned rapper, he was an introverted kid trying to navigate Los Angeles. Ask around and you’ll get the same story: the Kendrick we see today is the same mild-mannered child from 1990s Compton who, as a preteen, pedaled his bicycle through the neighborhood, ate Now and Later candy, and played basketball and tackle football with his friends. Kendrick was quick on the court, with nice dribbling skills and a reliable jump shot (though in later songs, he’d admit that it wasn’t quite good enough to take him to the NBA). He had dreams of going pro, much like other young black boys in economically challenged communities. In a place like Compton, with its prevalent gang culture, there’s a myth that black and Latino children are destined only for the streets, or that they can make it out only by creating music or playing sports at a high level. Some join gangs or sell drugs, but to spotlight that narrative alone is to ignore the support system in towns like this—the mothers, fathers, activists, and local leaders who project positive images to which the youth can aspire.

Compton wasn’t always Compton: Before World War II, the city was majority white, with racist policies that prohibited black families from moving there. In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned those laws, and by the early 1950s, black families started buying houses, much to the dismay of the whites already living in the suburban enclave. White people fled the city, fearing that their property values would plummet due to integration. The black population in Compton rose to 40 percent by 1960; a decade later, the neighborhood was 65 percent black. Crime began to rise due to growing unemployment, and in 1971, a gang called the Crips formed.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

The crew was founded by high school students Raymond Washington and Stanley “Tookie” Williams after they decided to unite their respective gangs to battle South L.A. gangs that were bothering them. The Crips soon became the biggest street gang in the city. In 1972, the Bloods were formed by Sylvester Scott and Vincent Owens along Piru Street in Compton, and were quickly established as a rival gang to the Crips. Members of other local crews had been assaulted by the Crips and were eager to join the ranks of the Bloods for revenge. By the early 1970s, middle- and upper-class black families started moving to nearby towns like Carson, Inglewood, and Windsor Hills. As a result, Compton became the epicenter for violent crime and gang activity in Southern California. Alonzo Williams, a DJ and nightclub owner who created the World Class Wreckin’ Cru (of which Dr. Dre was a member before he became a face of gangsta rap), remembers a different time in Compton.

He grew up in the town and used to walk through what are now considered dangerous parts without any issues at all. This was in the 1970s, before crack cocaine hit the streets, back when gangs existed but to interact with them wasn’t so dire. You could live near them, not be gang affiliated, and still feel safe. “Comp- ton was like any other city, man. It was cool,” Williams remembers. “We always had gangbangers, you went to the dances and they’d be there, but you’d walk right past them. Most of the guys you’d play baseball with or you went to school with, and there was a code of the streets that the gangbangers wouldn’t mess with the civilians. Gangbangers only fought with the gangbangers. They weren’t the ones looking to start no shit, but you don’t fuck with them.”

Crack cocaine changed everything. Gang activity grew out of control, and money was the new motivator. Williams also saw the dynamic shift in his nightclub. In 1979, when he opened the famed Eve’s After Dark banquet hall, a small number of his patrons were gang affiliated; by 1990, when crack was in full swing, much of his crowd was gang affiliated. “I had to change my personal attitude and dress code; everybody wanted to be a thug, everybody wanted to sell dope,” Williams says. “Everybody wanted to be hard. As soon as somebody got pissed off, they claimed a set. That was how you got people off your ass. It became fashionable to be a gangsta. You just did it because of where you lived, you could claim it.” That mentality still exists, Williams says: “Today, a lot of these kids are claiming hoods just because they’ve been told, ‘You live over here, that’s where you’re from.’ A lot of them are not really with the gang life, they’ve just found themselves attracted to it because it’s still fashionable in 2019 to claim a set. Back in the day, you knew why you were with a certain set. Now a lot of guys are doing stuff off the strength that it seems like the hot thing to do.”

Kendrick was raised in a working-class environment, first in an apartment building along East Alondra Boulevard, then in a small blue house along West 137th Street with his mother, Paula Oliver, and his father, Kenny Duckworth. Kendrick’s parents had moved to Compton from Chicago’s South Side in 1984, three years before he was born. Kenny had lived in the notorious Robert Taylor Homes in Chicago and run with a street gang called the Gangster Disciples. Afraid that Kenny could end up dead or in prison, Paula put her foot down: He’d have to quit the crew or their relationship was over. “She said, ‘I can’t fuck with you if you ain’t trying to better yourself,’ ” Kendrick told Rolling Stone in 2015. “We can’t be in the streets forever.”

Kenny and Paula packed their bags and traveled to California with just $500. They were headed farther east, to San Bernardino, but settled in Compton after Kendrick’s aunt Tina put them in a hotel until they could make ends meet. To sustain themselves, Paula did hair and got a job at McDonald’s while Kenny worked at Kentucky Fried Chicken and hustled on the side. Times were tough, but they eventually saved enough money for a more stable lifestyle. Then Kendrick was born—on June 17, 1987. As a child, he was a thoughtful wanderer who quietly observed his surroundings. That’s not to say he wasn’t fully present, but he found inspiration in the nuance of everyday existence. Kendrick, by his own admission, would sit in the corner and carefully watch what happened, taking mental notes on the scenes that unfolded.

Even from a young age, he had the makings of a great scribe, yet he wouldn’t pursue creative writing until he reached middle school. He was a perfectionist, and one can hear that approach in the poetry he wrote about his youth. Neighborhoods are described with pinpoint accuracy, down to the local landmarks and everyday voices that used to soundtrack his block. On good kid, m.A.A.d city, for instance, we hear actual characters from the community—the friends, the devoted church lady, even Kendrick’s parents—coming together to contextualize the rapper’s life story. On this work and others, he gives ample weight to the good and the bad in equal measure. By connecting lyrically with the Crips, Pirus, and everyday residents, Kendrick envisions a united Compton in which they all live harmoniously.

Kendrick was born just as gangsta rap began to gain traction with listeners beyond Southern California. The year he arrived, rapper Ice-T released a song called “6 in the Mornin’” that detailed the life span of a hustler selling crack cocaine. Through its vivid, lyrical imagery, the track opened a window into the perilous nature of life as a young black man in President Ronald Reagan’s America, where a so-called “War on Drugs” implicitly targeted and jailed inner-city minorities. Following Ice-T’s lead, in 1988, Compton quintet N.W.A (Niggaz Wit Attitudes) released its debut album, Straight Outta Compton, which cast a vicious light on civic despair and the police department’s rampant abuse of power. The pioneering L.A. group introduced a wave of rap that went deeper than the materialistic flash that emanated from New York at the time. Sure, the crew flaunted a little on Straight Outta Compton, but N.W.A wanted to address real issues in the harshest language possible. It was crude, raw, brutally honest, and shocking, but it also became a massive global phenomenon and set a benchmark for what gangsta rap would be compared with for years to come. “It’s the world before N.W.A, and it’s the world after N.W.A,” group member Ice Cube once told Kendrick in an interview for Billboard.

Artists like Ice-T and N.W.A documented the city in which Kendrick grew up, and the music would have a profound impact on him and L.A. as a whole. In 1995, at the age of eight, Kendrick went with his father to the Compton Swap Meet and saw rappers Tupac Shakur and Dr. Dre—the latter also a member of N.W.A—filming the video for “California Love,” the lead single from Tupac’s 1996 double album, All Eyez on Me. That was the first time Kendrick saw Dre in person and the last time he’d see Pac alive (he died in September 1996 of gunshot wounds after an altercation in Las Vegas, Nevada). Though Kendrick didn’t start writing rhymes straightaway, he didn’t forget the moment.

Maybe it was the sense of community that swayed him: Tupac and Dre were superstars, yet there they were in a shiny black Bentley, offering a lasting experience to everyday people. It showed Kendrick that local love was stronger than global fame, and no matter how big he got, in whatever profession he chose, it didn’t mean anything if he couldn’t celebrate his victory at home.

Excerpted from The Butterfly Effect: How Kendrick Lamar Ignited the Soul of Black America. Copyright © 2020. Available from Hachette Australia.