In the sunny corner of a Melbourne café, Mark Lizotte sits coiled like a spring. He’s eyeing a large beetroot juice and exquisitely presented fruit salad but holding out for one crucial detail. “This conversation is not gonna go far unless I get caffeine,” he says, pushing dark glasses towards a low-slung black baseball cap. The disguise might be a hangover from his pop idol days as Johnny Diesel. But if that experience taught him anything, it’s never to settle for good enough.

Does anyone still call you Johnny?

Yes. [Squeals] “Johnny Diesel!” That snapshot is everything to them. They know I’ve made albums after that but I’ll never kill it.

Your website displays 68 releases, going back to the first Innocent Bystanders single in Perth in ’84. Do you love all those babies equally?

There’s this kind of healthy detachment I feel with all of my songs. I know they came through me and everything but ultimately I know they just turn back into the soil of the universe [laughs]. I guess that’s a defence mechanism on my part too. But I play them so much that they come out different every night and I just allow them to. Records are just one destination for a song. It’s like sex or a great meal. You can’t go back to that again.

How do you look back on that first rush with the Injectors?

It was a great mechanism for me. I wrote to fit that thing that we had: bass, drums, one guitar, sax. It was like a little jazz combo but cranked up, bluesy. [The Rolling Stones’] Tattoo You was probably my most played album in the years before that.

How crazy did it get?

Ibiza [circa 1990]. As soon as I got there I realised, “This is just an excuse.” We were the only band that played live. Everybody else mimed. Grace Jones was there and Milli Vanilli and Fine Young Cannibals and Swing Out Sister. And there’s us. That’s where I met the Zappa family. Dweezil and Moon were reporting for MTV. We all sailed out to this beautiful island and Dweezil was like, “I’d really like a swim but I didn’t bring any bathers.” Five minutes later, Grace is on the shore with her legs up in the air: “Here, Dweezil, you can use mine!” I’m like, “There’s Grace Jones and I can see what she’s had for breakfast.” That was only months after we won all those [ARIA] awards.

Did that bubble burst or did you pop it?

I’d go crazy when I’d see my face in those Dolly magazines. “I don’t wanna be next to Jason Donovan!” But what was really taking over my life was this feeling that I just did not think there was another album in this band. I could see the machinations turning, producers coming out of the woodwork. I could see we could make another record that sounded like the first one and that, to me, was really frightening. I called a meeting and said, “OK, we’re gonna do one last tour.” My managers were like, “I hope you know what you’re doing.” I stopped drinking on that tour. I sat on my own and read books. The party was over.

Are you still teetotal reading guy?

As of about 10 years ago, I don’t drink at all. I realised that adrenaline, for me, was not a good combination with alcohol. All of the instances where furniture had been thrown… all were because of alcohol. I have been known to go into the crowd and take people on during a gig. Not good.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Were you trying to leave something behind when you moved to New York at the end of the Nineties?

Well, the first solo record [1992’s Hepfidelity] was a nice, slow sort of burn. I made the blues record with Chris Wilson [1996’s Short Cool Ones], which was really engaging and fulfilling for me musically. Then yeah, New York was a circuit breaker. I went back to being unsigned. [Laughs] In another 10 years it’ll be like, “What’s signed?” But yeah, that was the beginning of the cottage for me. Whether I knew it or not.

You tried to ditch the Diesel handle then. Are you at peace with it now?

That very year, 1999, they start putting up these billboards for jeans. [Diesel] was just breaking into the States. I don’t even think about it anymore. It’s only when I see my name on one of those scrolling LED signs: “Diesel… Puppetry of the Penis…” [Laughs]. It’s just a word. You can be called the Flying Burrito Brothers. You get used to anything.

You’ve been digging for roots since Short Cool Ones, 20 years ago. You’ve done Project Blues, Under the Influence, now Americana. What makes a man want to play his heroes’ songs as he gets older?

I think it’s obsession. It’s hat-tipping. It’s also maybe wanting some recognition from mummy and daddy, you know? “Please tell me that I’ve reached whatever status…” For instance, with the Neil Young song on this album [“Don’t Let It Bring You Down”], I’m really proud of that. Maybe he’ll hear it and go, “You ruined my song!” But I think I made some really cool embellishments that add to the darkness of the imagery. It’s a song about the debris of life and how we just step over it. I feel that in my own way.

You’re often called a guitar hero. The kid in you must kinda like that.

The only thing that’s heroic for me is I use really, really thick strings and they hurt.

—

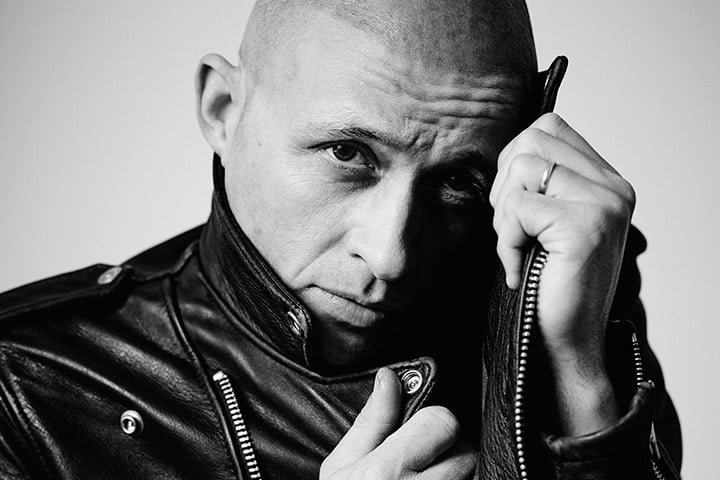

This interview is part of our Living Legend series, as featured in issue #777 (available now). Photograph by Joshua Morris.