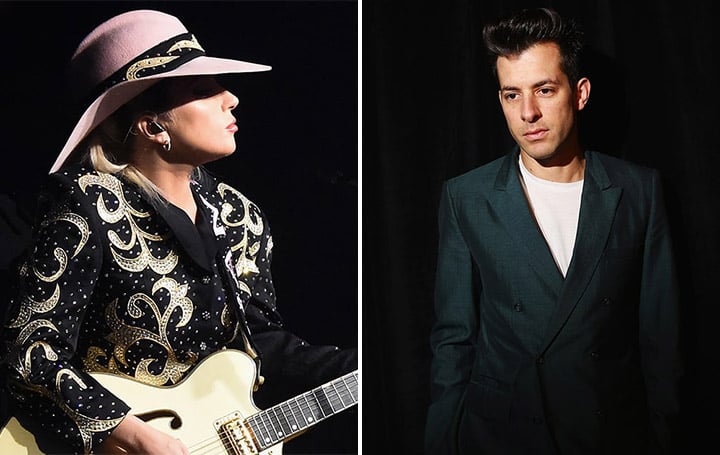

Mark Ronson remembers the first time Lady Gaga asked him to produce the album that came to be Joanne. “I don’t know what it’s going to sound like,” she told him last year, “but do you want to work together?”

It was probably inevitable that Gaga and Ronson would collaborate. Even though Ronson is about a decade older than Gaga, both grew up within blocks of each other on New York’s Upper East Side, and her private school would often have weekend dances with his. Ronson and Gaga first joined forces about eight years ago when Ronson enlisted her to add a vocal to “Chillin,” a track he was produced for rapper Wale.

“We had an hour free, so she came down to the studio,” Ronson recalls. “It was probably 11:30 in the morning and she was fully wound up and amazing. She seemed like the right blend of musical fanatic and eccentric New Yorker. I grew up around those types my whole life.” Ronson was also impressed that Gaga was a fan of his friend Sean Lennon’s work: “I thought, ‘Who is this girl talking about Sean’s voicings on the piano?’ Sean’s an incredible musician but not everyone is familiar with his albums.”

Cut to late 2015, when Ronson takes Gaga up on her offer to helm the follow-up to Artpop. At a studio in London, Gaga brought along a new song, “Angel Down,” which Ronson says was “quite moving.” At the end, Ronson says, “I was like, ‘OK, I think I can see how this could work. We’re into the same shit.'”

A few months later, the two arrived at Shangri-La, the historic Malibu studio currently owned by Rick Rubin. Since Rubin was between projects, Gaga and Ronson were able to settle into the studio for months, working on one of the year’s most eagerly awaited pop albums. “I’d never been there before and it was insane,” Ronson says. “Neil Young was in mixing a live album, so you’re coming in and seeing Neil walk past you on this hallowed ground. There’s something special about the place.” Out this week, Joanne was co-produced by Ronson and features collaborations with, and contributions from, a dizzying array of musicians, including Florence Welch, Josh Homme, Beck, Tame Impala’s Kevin Parker and Father John Misty. (Joanne remains such a secretive project that, of all Gaga’s collaborators, only Ronson volunteered to talk.)

On their first day at Shangri-La, Gaga and Ronson wrote the title song, which Gaga told Ronson was the “heart and soul” of the album. Gaga also took up Ronson on his suggestion to write about whatever was happening in her life or on her mind, resulting in songs about a late aunt who passed away before Gaga was born, her life as a dancer on New York’s Lower East Side and her personal travails (heard in the first single “Perfect Illusion”).

“Perfect Illusion” started with a Parker demo for a song he called simply “Illusion,” which Gaga and Ronson expanded on when they sat down with a piano and guitar, respectively. “The message in that song is quite personal for her,” Ronson says. “It’s this bastard love child of [Tame Impala’s] ‘Let It Happen’ and ‘Bad Romance.'” (As for the similarities to Madonna’s “Papa Don’t Preach” that some have pointed out, Ronson says, “Obviously, that was some kind of accident.”)

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Gaga’s guests came and went over those months at Shangri-La. She invited Misty to play drums, while Ronson, a major Queens of the Stone Age fan, reached out to Homme when he thought the track “John Wayne” needed a guitar part out of a Queens record. Homme wound up playing drums and co-producing. “Dancin’ in Circles,” the collaboration with Beck, began when Ronson ran into Beck and invited him to the studio. “For Gaga, it was like meeting her idol,” he says. “Beck is pretty much her favorite influential artist of the past 20 years. She was a fan girl at first.” The song morphed from an unplugged Beck song into what Ronson calls “classic Gaga, like ‘Alejandro’ and some of the stuff from Fame Monster.”

Meeting up at New York’s Electric Lady studio, Gaga and Welch conceived of “Hey Girl,” which Ronson says sounds like “two girls singing a soul record in the Seventies.” For an organic, earthy feel Ronson recruited many of the musicians he used on projects with Amy Winehouse and Rufus Wainwright, yet he says that producer Bloodpop, who came into the project and worked on some tracks, made sure Joanne didn’t sound retro. “We could have disappeared into our love for analog authenticity,” he says, “but he came in and shook it up in a great way. He brought it into the modern era.” Although Gaga and Ronson worked on the album for about six months, Joanne was so harried that additional songs were being recorded for a deluxe edition at the album’s ready-to-go mastering session.

Despite all the collaborators, Ronson feels Gaga was never in fear of being overwhelmed. “Her singing and writing are so strong and present and such a dominating color that you never nerve to really worry about that,” Ronson says. “She’s the glue. Everybody came in in such a natural way and heard what we were working on and found their way to fit in.”

Ronson feels the finished album takes Gaga’s music—and her power—to a new, unheard level. “Everything she wrote about was honest, and you hear that in how she’s singing,” he says. “I was just playing it at a photo shoot and this kid said, ‘This is amazing – what is it?’ When I said it was Gaga, his mouth dropped in shock. She’s made incredible records, but this is raw and exposed in a way that maybe she’s never sounded before.”