LONDON — “Boogie, Bobby, boogie,” Marshall Chess is saying over and over to Bobby Keys in the seat next to him, slamming out the phrase and laughing, as they talk about old-time saxophone rides.

“Booo-gey, Booo-gey,” Anita Richards, nee Pallenberg, is sing-songing in the back of the plane, making the word sound like an errant German nickname for Humphrey Bogart.

Boogie, a small brown and white puppy dog, is about to fall asleep in the arms of Anita’s husband, Keith. The doors of the midnight flight from Glasgow to London are about to close. Conversations buzz and hum. Only the tops of heads and the outsides of elbows are visible.

What could be nicer? Flying home from Glasgow in the midnight hour after two good shows before packed houses of people from out of 1957 (brass blonde ladies screaming and clutching at their heads whenever Mick showed his ass to the audience).

Contentment positively flows from seat to seat, the engines are about to rev, it’s five, four, three, two minutes to takeoff. When down the aisle comes a blue-jacketed airline official, all the way to the back seat where Keith and his dog recline. And the official says: “That dog flies by prior arrangement only sir, you’ll have to get off the plane.”

“What?”

“I’m sorry sir, I warned you in the airport. How you managed to slip by me on to the plane I don’t know but you’ll have to get off now.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“Look, I’ve flown BEA, TWA, Pan-Am.” Keith Richards, singer, composer, lead guitar player, Rolling Stone, is reciting a list of every airline he’s ever been on. “To San Francisco, to places you or this airline have never been…”

“You have to supply a box, sir.”

“I happen to know that section of the Geneva Convention very well; you have to supply the box. This is ridiculous. It’s an emergency. My wife and family are here, we have to get home to take my child to a doctor tomorrow.”

“I’m sorry sir.”

“We just want to get home. Is it that important? Just let us leave.”

“The rules, sir.”

“I know the rules. Get this plane going, we’re not moving.” Exit the official. Re-enter the official with two large blue Scottish policemen.

” ‘Ere wot’s the law doin’ ‘ere? Come to arrest us all, have you? Oy, you you, oy.” A big Scottish cop is doing his best to ignore Mick Jagger, who is lying flat on his backbone in a seat, naked to the waist save for a blue nylon windbreaker someone has thrown over him after he gave away his sweaty T-shirt on stage.

“Oy, oy,” Mick says loudly, a saucy schoolboy trying to get the police to notice. He reaches out to jangle at the cop’s sleeve. “Now, now chummy,” the cop says, leaning over. “No one’s done nothin’ yet, why should we arrest anyone?”

“He’s come to arrest the dog,” Keith says.

“Wot you doin’ ‘ere,” Mick demands of the cop, “A little dog like that. A puppy.” His face falls. “You should be ashamed.”

“Ooo called the law,” he wails. “Arrest us.”

“Chummy,” the cop says, “I wouldn’t give you the publicity.” “Chummy?” Mick demands. “Sir… look…”

“Don’t curse me, I saw you say fuck, don’t go curse me…” Beautiful, Mick. All they have to do is search the luggage and it’s 20 years in the Glasgow jail. “Anita,” Mick says, “Go find the captain.”

Beautiful, Mick. Mata Hari Anita, all crocheted stockings and tiger hot pants, sent to seduce the captain of the airplane as it stands on a runway in Glasgow.

“Goooo,” Mick googles. Marlan, Keith’s 18-month-old son, googles back and laughs. The cop is outflanked, bewildered, surrounded by little kids, slinky ladies, rock stars. Mick… beautiful.

“We’ll put him in Charlie Watts’ orange bag,” Marshall Chess the solution maker says, meaning the dog, “Is that OK?”

“Yes,” says the cop. “No,” says the airlines official.

“You brought him on this plane and now the two of you can’t agree,” Keith shouts. “How about mah vulture,” Bobby Keys yells out, “Can ah keep him up hyeah?”

“How ’bout mah rattlesnake?” Jim Price asks.

Words whizzing like bricks in a street fight and… the cops and the official are losing it.

“Ya Scots git, get off the plane.”

“Arrest us,” Mick demands.

A hurried conference at the front of the plane. Stewardesses and captains, cops and officials, the flight is 15 minutes late already because of one small dog and 20 crazies.

“We’ll link arms.”

“Arrest us,” Mick demands. “Put the dog in the orange bag and he can ride in the hold,” the official says.

“What’s your name?” Keith demands.

“Never you mind. It’s not important.”

“Ah, but it is. If this dog dies, I’ll see that it becomes important… If he freezes to death…”

They trundle the dog off and put him in the hold and an hour and a half later, the plane touches down in London. Boogie doesn’t freeze to death at all but instead comes spilling and sliding out on to the polished airport floor.

Everyone speeds home in chauffeur-driven Bentleys and long black Dorchester limousines and the incident is quickly forgotten, just another minor, laugh-filled moment with the Rolling Stones on tour. Or, as Bobby Keys shouted one sweaty night in a Newcastle dressing room, with his arm wrapped about Charlie Watts’ head, “Gawdammit Chawlie, rock ‘n’ roll is on the road agayn.”

—

In the five years since the Rolling Stones last toured England, they have made so much money through album sales and concert tours of Europe and America that they find themselves in the 97 percent tax bracket in their own country. They have become the first rock and roll band to be forced into stylish W. Somerset Maugham-type exile in the south of France.

Along with Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, they are the last of the utter superstar bands — modern-day lords totally cared for and looked after, whose only responsibility it is to keep their heads in a place that enables them to keep on making their music.

It’s been a year since Allan Klein had anything to do with representing their corporate interests. Their recording contract with Decca has lapsed. On their European tour, they were accompanied by Marshall Chess, the son of the good Jewish businessman who established and ran Chess Records. His presence on the English tour signals the start of something new for the Stones — incorporation on a scale no band except the Beatles has ever undertaken.

The Rolling Stones record label will most likely be distributed by Kinney National, which owns Atlantic, Warners-Reprise and Elektra. The deal has been in the works for months but the contract still remains unsigned. The Stones label will be run by their own international corporation based in Geneva, with branches in London and New York.

Marshall Chess and the Stones will direct activities. The Rolling Stones record logo will be a stuck-out tongue and the first album to carry it has a cover designed by Andy Warhol featuring a pair of bluejeans with a zipper that really works.

Entitled Sticky Fingers, it will be the first entirely new Rolling Stones album in the 17 months since Let It Bleed. The album has ten tracks: “Bitch,” “Brown Sugar,” “You Got To Move,” “Dead Flowers,” “I Got The Blues,” “Sister Morphine,” “Keep A-Knockin’,” “Wild Horses,” “Sway,” and “Moonlit Mile.” Only “Wild Horses” has been heard before, as a part of the Gimme Shelter soundtrack and as the final cut on a Burrito Brothers album.

The album should be out by the third week in April but there are still some vocals that may be re-recorded. A year of work has gone into it, about £42,000 (over $100,000) of time and effort.

Forthcoming albums should include solo efforts by Bill and Keith, Keith possibly together with Gram Parsons, the ex-Byrd and Burrito. The Rolling Stones’ corporate assets also include Mick Jagger’s house in the English countryside, left vacant by his move to France. It is being outfitted as a total live-in recording studio complete with cooks, fireplaces, and round-the-clock facilities. It can be rented for £2500 ($6,000) a week.

There is also the “rock truck,” £100,000 ($250,000) worth of 16-track equipment packed into a large trailer truck that has been painted flat khaki (“For camouflage,” Marshall Chess says). The truck converts any building it is parked outside into a studio. It rents for 1500 quid ($3600) a week.

Much of the energy and direction for what the Stones are about to get into comes from Marshall Chess, who bubbles nearly all the time and gets so knocked out by the music the Stones make, it sometimes seems he might be doing it all even if there was no money involved.

The Stones have spent their lives listening to Chess records. Now, with 29-year-old Marshall Chess to advise them, they’re going to make their own.

—

Empty King’s Cross Main Line station on a cold, clear Thursday that feels like November in New York. One penny for the toilets and the pay phones don’t work. The twelve o’clock train for Doncaster, York, Darlington, Newcastle, Dunbar, Edinburgh, and Aberdeen leaving from track eight.

Pianist Nicky Hopkins, who went to California for a week and stayed two years, is on board and off again, and again, snapping pictures of anything that doesn’t move, the station, Cadbury chocolate wrappers, as long as it’s typically English. Mr. Session Man, with a beautiful hangdog face and a camera always dangling from his neck. Bobby Keys and Jim Price, the Texas Horns, most recently on the road with Delaney and Bonnie and Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen. Bill Wyman and his lady, Astrid. Charlie Watts, dapper, being seen off by his father: “Awrite, Charlie, I don’t wanna go. Let me off.”

A trainman with a green flag in his pocket comes down the line closing doors. The two Micks, Jagger and Taylor, catch a later train. Keith misses that one too and is driven up. Sudden small flake snow comes swirling as the train eases out of the station to the North.

Newcastle, a gray, scruffy, soulful city on the Tyne River, in the part of England nearest Scotland. Without any sound tests and only a week of rehearsal, the Stones begin the tour there with two concerts. They are still one of the killer bands of all time.

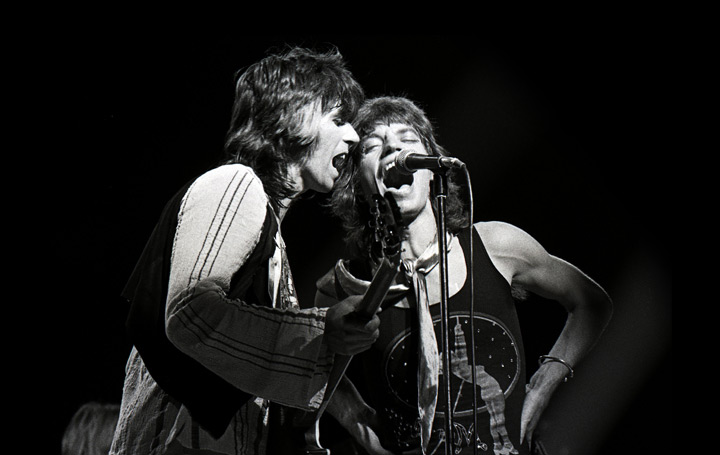

Opening with “Jumping Jack Flash,” Mick in a pink sateen suit and a multicolored jockey’s hat. Then into “Live With Me,” “Dead Flowers” off the new album, “Stray Cat Blues,” “Love In Vain” with Mick Taylor doing two totally controlled solos that soar nightly. Then, “Prodigal Son,” Keith picking and stringing on an acoustic guitar as Mick stands next to him and sings.

“Midnight Rambler,” as it breaks down, is six, eight, ten, or 12 bars of basic blues, depending on how long it takes Keith to sling one guitar over his head and get another on and tuned and launch the song’s driving riff. Then, everybody pushing to one ending and the psychodrama begins, with just the bass pulsing away and the lights blue and eerie in Mick’s face.

Off comes the studded black belt, Mick is down on his knees, “Beggin’ with ya bay-bay, uh, uh… Go down on me bay-bay, uh, uh.” Rising slow and sinister to “Wahl, you heard about de Boston…”, stretching and stretching the second syllable, dangling the belt up behind his shoulder, then slashing it to the floor as the band crashes it in back of him and all the lights come up. “Honey, it’s not one a’ those.”

“OOOOOOOOOooh.”

Every night, there’s this sharp intake of breath, nervous giggles, little girls finally getting hip to what it’s all about as that belt crashes down and the band hits everything in sight as the lights come up on Mick, hunched over and prowling like an evil old man. Then “Bitch” with Bobby Keys and Jim Price blowing circles you can stomp in. “A song for all the whores in the audience,” “Honky-Tonk Women,” followed by a long, unrecognizable intro that always fools everyone because it leads into “Satisfaction.”

Most nights the crowd is solidly crazed by this point, rocking down the aisles, idiot dancing in the balcony, middle-aged ladies bumping obscenely in toreador pants (1957!), skinheads gently waltzing ushers round in circles. Rock ‘n’ roll may never die. “Little Queenie,” “Brown Sugar,” and then “Street Fighting Man” with Mick flinging a wicker basket of yellow daffodils into the house, petals floating down through spotlight beams as he leaps four feet in the air and screams.

Between shows the dressing room is quiet, calm, Bill asking no one in particular, “Do ya remember carryin’ an amp about Newcastle in a wheelbarrow?” as Keith jiggles Marlan up and down.

The Rolling Stones Album Guide: The Good, The Great, and The ‘Angie’

The second show at Newcastle is better than the first. Nicky Hopkins, cigarette dangling out the corner of his mouth, two bottles of whiskey on the piano, honky-tonking all the way, moving only from the wrists down. Chip Monck, the voice of Woodstock, right beside him with headphones on, doing his gentle 1958 duckwalk skate, cueing lights, monitoring feedback, ripping cords.

Keith, corkscrewing his body in ever tighter circles as he gets off, his earring swings into view, turning his back to the audience to see-saw into Charlie’s big Gretsch bass drum. Charlie is chopping things to rhythms, doubling up, drumming against himself, jack o’lantern face turned to one side, mouth open.

“Curtain call, chappies,” a Stones roadie says when it’s over.

“They don’t do curtain calls,” their publicity lady says. “No one is leaving,” Chip Monck says, sticking his head in the door.

“Should we then?” Mick asks.

“What do we do?” Keith says.

“Uh, ‘Peggy Sue’?”

“They pour through a narrow door and file back on stage into a cosmos of light and noise for their first encore in three years (not a single one on the European tour): “Sympathy For The Devil,” followed by Chuck Berry’s “Let It Rock.”

—

The concert over, there’s a long white starched table set for 40 people back at the hotel. A beggar’s banquet trailing away in the middle of a ballroom. Forty clear glass tumblers all in a line. Knife, spoon, fork set perfectly and repeated 40 times. At two in the morning, surrealism, Rolling Stones variety.

Marshall Chess sits across from Mick. Mick’s lady, Bianca, sits next to him in a white linen cape and a wide-brim pushed-back hat. She has a face so beautiful as to be insolent: high cheekbones, sweeping facial planes, a cruel mouth, features that became Oriental in repose.

“More than 20 minutes on a side and you lose level,” Marshall is saying, “You know that. It’s how they cut the grooves. So we have to work out the running order…”

Down the table a ways, Jim Price asks Charlie Watts, “You dig Skinnay Ennis, the cat who blew that solo in ‘We Meet And The Angels Sing’?”

“Fantastic,” Charlie says, sounding a little like Cary Grant.

“That was Ziggy Elman,” someone says.

“He’s from mah home town,” Jim Price smiles.

“Who?”

“We can begin distribution right away to key spots throughout the States. We’re gonna use one picture world-wide to advertise it and it’ll have an international number. That’s a first,” Marshall says proudly.

“He’s dead,” Jim Price notes.

“Who?”

“Skinnay Ennis.”

“You mean Ziggy Elman, man?”

“They’re both dead,” Charlie says sadly, shaking his head.

“Henry Busse too,” Jim says. “On ‘I Can’t Get Started With You.'”

“Fantastic,” Charlie says, exploding it like a soft cymbal crash with brushes.

“We’ll send you a test pressing by air,” Marshall says, “and you send me back a dub…”

“You’ll send me one too,” Charlie demands loudly.

“We will, Charlie,” Marshall says, a little surprised.

Charlie smiles. “Just addin’ to the bravado.”

“Ah am going to burn down this goddahmn hotel if ah don’t find mah suitcase,” Bobby Keys says, in a voice made louder by the fact that it’s in England. “Goddamn… ah’ll throw Chawlie Watts out a window… What’s that? Slide one of them on mah plate, lady,” he orders a waitress. “You know what these rolls are good for?”

“Oh-oh,” Jim Price says softly, knowing the answer.

Whang, a roll comes spinning through the air.

“You know what these glasses are good for?” Bobby asks rhetorically.

“Will you do it that way, Mick?” Marshall asks. “Will you? If we cut ‘Moonlit Mile’ to four verses and make up a running order so that the guy in the States can get started on the sleeves?”

Mumble mumble, Mick’s head is down, speaking to Bianca. It’s four AM now. He raises his head, looks a little glazed. He says, “What, Marshall?”

—

One morning in a TV floodlit hotel lobby, a very proper BBC interviewer asked Mick Jagger, “Ahah, ahem, John Lennon, in his interview in Rolling Stone magazine, said that the Rolling Stones always did things after the Beatles did them. Are you then too planning to break up?”

Mick’s face widened and he broke into his haw-haw laugh. “Charlie, are we goin’ a break up then? Are ya gettin’ tired of all this?” As Charlie crept around the outside of cameras asking, “Who’s he? Who is that?”

“Naw, we’re not breakin’ up,” Mick said, “And if we did, we wouldn’t be as bitchy as them.”

The Stones, still together today, are separately becoming the people they want to be. Charlie, the oldest, could be drumming with a jazz quartet, playing nightly gigs in small clubs in Sweden or Denmark. Bill wears fine clothes, likes white wine, smokes small cigars. Mick Taylor is younger than anyone, as much a part of things as he wants to be, a fine blues guitarist. Keith drives the band on stage, pushes the changes. He and Anita are the undisputed king and queen of funk and inner space. Mick Jagger, 26-years-old, is very much the man of the world, always whoever he wants to be on a given night, in the process of becoming European.

Consider the madness they have witnessed together. Ian Stewart, called “Stew,” looks like just another roadie as he hovers by the amps while the Stones are on stage. He plays piano all over their albums and has been around since the beginning.

“In a place like Birkenhead, say,” Bill Wyman says, “we’d go out and start, ‘I’m gonna tell you how it’s gonna be…,’ three bars and unnnnnh they’d come sweepin’ all over the stage and finished… back in the hotel with a thousand quid. Girls leapin’ from 40-foot balconies and arrows in the paper next day showin’ where she jumped from…

“I remember only one audience back then that didn’t like us from the start. All the factories in Glasgow close at the same time. Scots week, they call it. They all go to Blackpool and drink and we played there on the last Saturday night. They were evil. A six-foot stage so all you could see was heads. About 30 of ’em spittin’ on us. Long hair, I guess, and their birds fancyin’ us. Keith was covered in it. Finally he said to one guy, you do that again and… well, the guy did it. Keith kicked him in the head. They all come at us. We ran right into a police car.

“Stew come back to the hotel later with a little piece of wood hangin’ off a wire, a little tiny piece, and said, here’s what’s left of your piano. Smashed the amps, twisted cymbals. Wasn’t our gear though, we were usin’ someone else’s.”

“You’ll never see that again, I don’t think,” Bill says.

One night in 1965, on their first American tour, the Stones play at Ithaca College in upstate New York. No fainters or swooners, no screamers or jellybaby throwers, no roaring insanity. For the first time in a year and a half, the Stones are able to hear themselves live.

“Bloody awful we were,” Bill smiles.

—

Saturday night in Coventry, Mick Jagger is wearing a black and white checked jacket, sitting with hands folded, drinking red wine at a restaurant between shows.

“Forget my name you bastard, you and all your Rolling Stones,” a girl cries as she’s hustled out the door by one of the Stones’ managers.

“Boring, isn’t it?” Mick sighs, taking a sip of wine.

Bianca is talking about going gambling somewhere. A few nights ago in Manchester, Mick, Marshall, and Bianca found a casino that only let you lose and Mick dropped more than anyone, about three hundred quid. “You even play gin rummy in a foreign language,” Marshall tells Bianca. So far on the tour he owes her $8000 in rummy debts. “But the dealer in Manchester, he was terrible…”

“Dealing out of a shoe, probably had three decks in there,” someone offers.

“Ah, if we had won, we’d be sayin’ how good he was, wouldn’t we, Mick?” Marshall asks.

Mick looks up, pauses, and says, “I really don’t care.”

And there is this silence that seems to grow around the phrase, before and after, like when the Stones sing “Wild Horses” on stage and no one knows what to do with it. It stops everyone cold. They have to think.

Mick doesn’t care.

“Oh, that was last night, huh?” Marshall says, picking up on it.

“Tu vas changer le choix?” Bianca asks Mick. The first show was notable. A quiet country audience in peaceful Coventry was sitting politely and watching. Mick didn’t throw them the flowers in “Street Fighting Man” and Chip Monck played “God Save The Queen” as soon as it was over.

“Drunken bitch,” Mick notes, as one of the band’s ladies wobbles by. “She won’t lose weight that way, will she?” He sighs, “There’s nothing to do but bitch, is there?”

“Intermission’s over,” a manager says. “Time to go.”

“No,” Mick says flatly, “Don’t wanna. Oh fucking why? They sold all the tickets here in three hours and then they come and just sit there.”

“Let’s go out and tread the boards then, Mick,” Charlie says, doing a little soft shoe, making him smile.

“Yeah. A tap dance. Oh, it’s all right. Why do they have to sit there, though? C’mon then. Same show, if it’s the same audience. Maybe we’ll even knock out a number and go home early.”

And of course, just like in the movies, the second show is a bitch and Mick and the boys incite the crowd to riot. Charlie cooks. The lights go all purple and green against a white painted wooden stage floor. Everyone sweats and goes home happy.

In Bobby Keys’ dressing room before one show, his ever-present cassette tape recorder is spooling out Buddy Holly singing, “Are you ready? Are you ready? Ready, ready, ready to, rock and roll.”

“Mah golden saxophone is comin’ up now,” Bobby says as the next song comes on. Indeed, Bobby Keys who looks about 18 after a good night actually played with Buddy Holly, recorded with him at K-triple L radio in Texas, and was on the first Alan Freed show at the Brooklyn Paramount which featured the Everly Brothers, Clyde McPhatter, Buddy Holly and the Crickets, all backed by Sam “The Man” Taylor’s big band. Bobby is pushing 29. “Ah been on the road 16 goddahm years,” he says, “That whay I am the way I am.”

And so saying, he pulled on his black tigerskin and velvet jacket, over his special ruffled black shirt and went out on stage to blow with one of the last real rock and roll bands around.

—

“Oh, who listens to Berry anymore,” Mick Jagger asks on the flight to Glasgow. This day, he is wearing a long brushed grey suede maxi-coat, a tight ribbed sweater, and a blue printed cap perched on the back of his head. He is looking very French.

“I mean I haven’t listened to that stuff in years. Rock ‘n’ roll has always been made by white suburban kids, bourgeois kids. Elton John is a fine example. For God’s sake, I listen to the MC5.

“Rock ‘n’ roll’s not over. I don’t like to see one thing end until I see another beginning. Like when you break up with a woman. Do you know what I mean?”

In Glasgow, one of life’s cheap plastic dramas: Green’s Playhouse. Paint peeling off all the walls. Six inches of soot in the air vents. Bare bulbs backstage and fluorescent tubes for house lights. The third balcony is closed to “keep the raytes doon.”

A group that’s been together for a week is filling in before the Stones’ first set and the first two numbers they do are Jagger-Richards compositions. Third generation rock.

Rab Monroe, their lead singer, on his way into the dressing room passes Mick Jagger, on his way out. A hot, seedy cramped corridor in the basement of a Glasgow theater. They actually brush shoulders. Twenty-three-year-old Rab… 26-year-old Mick. Kid, you’ll never know.

Mick misses the train to Bristol even though he’s on the platform when it pulls out. He doesn’t want to run for it. No one expects Keith, Anita, baby, and dog to make trains. Along with Gram Parsons they’ve become a separate traveling entity.

The kids in Bristol may be sharp as a pistol but the ushers are thick, bearded wrestlers in silk suits who stand facing out in front of the stage and stop anyone from dancing. Mick celebrates “Street Fighting Man” by placing small mounds of flowers on each of their heads, a baptismal offering. The kids dance. The Stones do an encore.

During the second show, an usher drags a pretty painted young girl off stage. Mick kicks him in the shoulder.

In Brighton, a German magazine crew in wet leather and plastic chosen by Erich Von Stroheim from central casting, come looking for “Mikk Jagga, ja?” The hall is a big barn of a discotheque, so hot no one can stay in tune. A greasy, sweaty gig. Three kids down front do a snapper in the middle of “Little Queenie” and for the rest of the song their faces blur and flow with the music.

In Liverpool, Mick shows up with his hair cut. Glyn Johns is along to record. Keith has missed the train. The jet that will get him to the theater in plenty of time breaks down. So does the prop they replace him with. He arrives an hour late with Anita, who is essentially naked in silver lame and a push-’em-up, grabem bra over what looks like bare skin.

Mick and Bianca slouch on a couch waiting. “You been on the road for 18 months now Marlan,” Mick says. “How do you like this life?”

The Stones finally go on to do the only bad show of the tour. Others have been less than perfect musically but there has always been electricity, excitement, some kind of contact. This time, nothing. For the Stones, that is. The set itself is not unrepresentative, and for someone else it might be a good show.

In the dressing room after, Bill looks sadder than usual, really unhappy. “I’m just saying don’t be so brought down,” Keith tells him.

“I just want everyone to say it was shit,” Bill says. “They queued for five hours and…”

“They don’t know the difference Bill,” his lady says. “They enjoyed themselves. It doesn’t matter to them.”

“We were shit,” Bill insists.

“Ah was great,” Bobby Keys beams, trying to make it better. “Ah was fantastic. Ah carried y’all.” There are a few weak smiles.

“I don’t care,” Mick Jagger says, “I don’t give a shit. When I’m on stage, maybe, but now I’m off. Right now, I’m petting this little dog here, that’s what I care about.” He gets off the couch and walks out slowly.

“What we need is a joint,” someone says.

“Yeah. Where are the dope dealers?” Gram Parsons asks. He sticks his head out into the hall. “Dope dealers?”

Two minutes later, Mick Jagger, who some will tell you is the devil incarnate, so blase that he can’t be bothered to care about something once he’s done with it, could be found on the fourth landing of a staircase that led to the room being held in the arms of his lady. They looked nice together.

In Leeds, the Stones played a university student union. Before the show, they sat waiting in a cafeteria, squeezed into leatherette booths at fake formica tables like Archie, Juggie and the gang down at Pop’s for a soda. During the show, one of their ladies threw up politely, twice, and left.

Everyone in London washed their hair and stood in line on Sunday for the Rolling Stones at the Roundhouse, a metaphysical gig of the first order, a long time coming. The right band in the right place and a chance to see a city turned out.

Scalpers huddled and quoted: “Seven pound for a ticket — wait a minute, you’re a student, ain’t ya? Six.”

A girl faints just outside the stage door and is carried in. Forty-two people crowd the dressing room. The showers run to keep the cans of beer and coke cold. One heavy spade says to another, “Are you black, man?” and passes a joint. Bowls of sliced lemons for the tequila, bottles of tequila, bananas, nuts, raisins and a room that’s a groupie’s who’s who.

Dave Mason in a forest green velvet jacket, ex-Mad Dogs Jim Gordon and Snaky Jim Keltner. Eric is coming. Chris Jagger. Outside, Family, Edgar Broughton, the Faces. Upstairs, John Peel, Tom Donahue, the entire pop press, the straight press, the music business, a gaggle of PR men, a clutch of record execs, a congregation of super-dressed screamer freaks.

Joyce, the Voice, whose trip it is to be all trippy and sometimes grab the microphone on stage for unscheduled raps, has somehow slipped through the cordons and is slugging away in the dressing room like she was born to pop stardom.

“Excuse me,” she says, talking directly to Bianca, “but didn’t I see you with Osibisa in their dressing room last week?”

What? What is this? Hold on — Joyce the Voice has just asked Bianca, of the inscrutable face and blinding smile, of the mysterious eyes and gin rummy ways, she has just asked Mick Jagger’s lady, “Aren’t you a groupie for this band I know?”

“What is Osibisa?” Bianca asks politely.

“Oh wow,” Joycie straightfaces, not knowing when she’s been cut dead. “There is someone with your exact vibration around. I mean, like a twin sister. You know? Someone who is walking around with your face.”

Bianca rolls her eyes white upwards. They remove Joyce.

“Hoo’s Mick Jagger now,” an old man asks. “Iss not for me, an autograph for a little girl, a spastic she is, no legs neither.”

Out in the hall someone is trying to sign Gram Parsons to a contract. “Apresmoi,” he says, as the door swings open, “le deluge” and a stream of people spittle out, having been asked to leave.

One hour late the second show starts. A tough set in which the mikes go dead during “Street Fighting Man” and ping pong balls, yellow flowers, and white confetti pour onto the stage. The band is celebrating, out of sea green champagne bottles. The tour is over and it may be a while before there’s another. Rock and roll is a young man’s game.

As for the audience, well, they’re so super-hip and spaced, they dance only because they’re supposed to. In London, the Stones are a social phenomenon.

You can’t dance to a social phenomenon. The Rolling Stones are a good band. Pick up on them sometime.

—

Originally published in an April, 1971 issue of Rolling Stone.