Excerpted from the October 19th, 1978 issue of Rolling Stone

Two rent-a-cars carrying Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers roll toward Vancouver International Airport for an early-morning flight back to Los Angeles, where the band will take a two-day break from touring before heading to England for more shows. Suddenly, one of the cars pulls up alongside the other. Wildly motioning to roll down the window, drummer Stan Lynch shouts, “We’re on! Right around 102.”

This is tantamount to red alert. Hands dart to the radio dial, and these weary rockers come alive with schoolboy fervor. Hearing the last notes of their new single “Listen to Her Heart” on AM radio, the Heartbreakers – Petty, Lynch, guitarist Mike Campbell, keyboardist Benmont Tench and bassist Ron Blair – give themselves a whooping cheer and continue on to the airport.

Once on board the plane, the band members happily collapse for the two-hour flight. All except for Petty, who orders coffee and, in an uncommonly talkative mood, reflects on the past two years. “Everything’s banking on that one song right now,” he says in a slow drawl, “and I’m prepared for the worst.”

Though their second album, You’re Gonna Get It!, has gone gold, they still need a big hit single to make their mark in the platinum-oriented business. The problem is that “Listen to Her Heart,” the second single off the album, contains the line “You think you’re gonna take her away/With your money and your cocaine.” And despite record-company and radio-station pressure, Petty has refused to change “cocaine” to “champagne.”

“I mean,” says Petty, “first of all, it’s anti-cocaine. I don’t even like the stuff. And second, what’s champagne going for these days? Two bucks a bottle?”

The last three days on the road illustrated why a hit is so vital to this band on the verge of stardom. There had been a riotous 3,000-seat sellout in Seattle one night, a half-full house in Portland the next, and a curious club-full of Vancouver teenagers the third. Through it all, Petty and band had gladly shared rooms, met the local media and collected fanatical concert reviews. But, says Petty, “The last thing I want to be is a critics’ band.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Today, for the most part, that doesn’t appear to be a problem. “Did you see the reviews in England?” Petty asks, brushing his yellow hair out of his eyes. “They criticize us because we’ve become too L.A.-ised. Comparing [the new LP] to a Linda Ronstadt record is really funny to me. And I don’t care, to tell you the truth. I really don’t care if they want to give me shit about where I live. I could live in New York and do the same album. How dare they think that we’ve become too L.A. We’re saving the place. Don’t give me shit.”

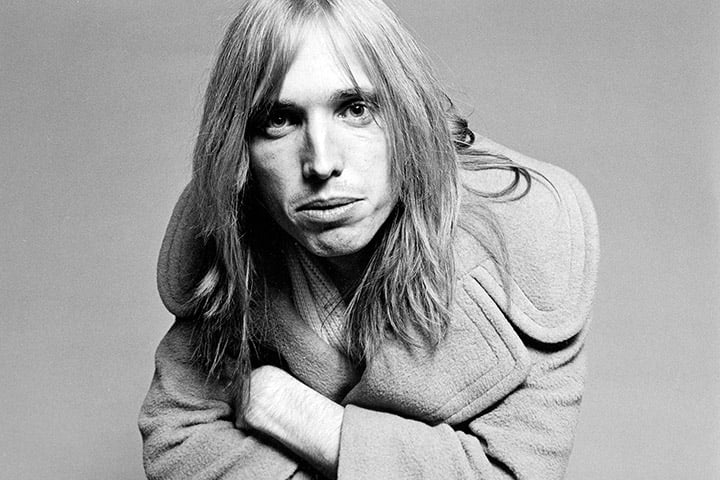

Tom Petty performs in 1977.

The son of a Gainesville, Florida, insurance salesman, Petty was toothy and unpopular in school. After quitting school at age 17, Petty eventually became a local bar sensation with his band Mudcrutch. Watching other regional stars like Duane and Gregg Allman find fame out West, he brought a Mudcrutch demo to L.A.

His first day there, Petty began making calls from a pay phone on the corner of La Brea and Sunset in Hollywood. By the end of the day, he had collected offers from Capitol, MGM and London. A week later, Petty returned to Gainesville with seven such offers. The day before the band was to move out to L.A., the phone rang with yet another deal. The group signed with Shelter, which at that time was co-owned by Leon Russell, and the label’s president, Denny Cordell, sponsored Mudcrutch’s move to Los Angeles. “But we did the L.A. freakout,” recalls Tench, who along with Campbell was also a member of Mudcrutch. “We fought over songs, over having been together too long, and we broke up.”

Petty and Campbell stayed together to try and salvage the Shelter contract. But an attempt at a solo Petty album with L.A. session men came off stilted, and Petty found himself “hanging out at Leon Russell’s, getting desperate. I didn’t know how to get a band together.”

The solution came while Petty was driving back from Cordell’s Malibu house one afternoon and decided to swing by a Benmont Tench demo session. He found a roomful of familiar Gainesville musicians. “We played together that day,” he says. “The next day I asked them if they wanted to start the band.”

The band became the Heartbreakers, and their goal was to combat “disco trance music” with “the kind of rock that used to come blasting out of the AM radio when every song was a new Creedence or a new Stones, and all you wanted to do was crank it up.” The group finished its first album in two weeks.

By the time Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers was released, in November 1976, Petty says, “Everybody white, in a band and under the age of 25 was a punk.” With an album cover that pictured Petty in black leather and bullets, the band found itself categorised. The group took early jobs playing with Blondie and Tuff Darts, but Petty spent most of his early interviews pointing out that he was not a punk rocker. Sample quote: “Call me a punk and I’ll cut you.”

When the group’s album went unadvertised by ABC, which distributed Shelter, Petty’s quotability helped bring the group to the public’s attention, particularly in England. Opening for Nils Lofgren on a British tour, the band was quickly invited back as headliners. “American Girl” and “Anything That’s Rock ‘N’ Roll,” both from the first album, became hits in England.

Petty’s anti-punk reputation also earned him an early confrontation with Johnny Rotten. “We were walking into our hotel lobby in England,” remembers Petty. “I hear this snotty voice saying, ‘Oh, it’s the American pop star Tom Petty.’ I ignore it, check into the hotel, and Stan and I start walking toward the elevator. We hear the same voice, kind of whining, ‘There the hippies go. Bye-bye, Tom.’ At this point, Stan wheels around and starts heading for whoever it is. He wants to kill.

“Well, it’s Johnny Rotten, surrounded by French journalists. Stan has to be restrained. I went over there and said, ‘Who the fuck are you talking to?’ Rotten immediately went into his wounded-punk act, says nothing. There ain’t no Robin Hoods in rock, man. All that punk shit was just a little too trendy. Costello’s OK. We played with him, but I couldn’t call him Elvis.”

Fired with confidence, Petty returned to the U.S. and found that “Breakdown” was starting to hit on the charts. He had been particularly vocal overseas about being taken for granted by ABC in America, so when he arrived to renegotiate his contract after the success of “Breakdown,” there was a phalanx of lawyers and label executives waiting for him. Petty emerged from the closed-door meeting wearing a triumphant smirk.

“Ever since then,” says one ABC secretary, “that whole band comes around here like they own the place. Nobody really knows what happened.”

According to Petty, “I told all the lawyers that I had made a living a long time before I made records, and if I couldn’t get a fair deal, I just wouldn’t record anymore. I meant it. I was fed up. We were being treated like we were stupid. We are not stupid.”

Then they gave in to your demands?

“No,” says Petty. “I took a switchblade out of my boot and started admiring the edge. Then we made headway.”

Besides a substantial royalty increase, Petty and the Heartbreakers also received a delay in delivering their second LP. With the first album rising on the U.S. charts, the group took off on a nonstop tour that lasted through most of 1977.

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers at the Whisky A Go Go in Los Angeles in 1977. Credit: Chris Walter/WireImage

“During that year,” says Petty, “I had my fill of hearing 7-million-selling albums and all the other records that came out with the same million-dollar slick sound.” So when the group entered the studio to record its second LP, “We decided to go for a feel, an acquired taste.”

The album was recorded in three months at Shelter’s L.A. studios, an abandoned Armenian nightclub way down on Hollywood Boulevard. The only view of life outside the single-red-bulb-lit studio is through a porthole, out of which one can see a gay porno theater. While recording, the group marked time by waiting for the “Gibbon Woman,” an elderly woman who passed by every day at the same time and shrieked like a banshee.

Originally titled Terminal Romance – “It was a real rocky romance year” – the album was renamed You’re Gonna Get It! at the last minute. Petty and manager Tony Dimitriades conspired to notify their good friends, the ABC executives, of the name change by anonymously mailing them pieces of paper scrawled with the words “You’re Gonna Get It!” By the time Dimitriades phoned ABC for its reaction several days later, he found that the company had called in the FBI to investigate. And one executive, coincidentally fired the same day he received the note, still believes himself the object of some cult conspiracy.

“And that is how these stories about us start,” says Petty. “We are what we are. We’re a working band. I don’t know fuck about the U.N. I’d rather sing about rock & roll and chicks. I think I’m much more in touch with that. Then again, you never know when you might write a positively brilliant album about Red China – as long as the songs are good.

“We still haven’t made the definitive record. This one is better than the first, and the first one was pretty good, but one day we’ll get it perfect. We haven’t even touched our potential.”

As the plane begins its descent into L.A., Petty turns to me and adds, “Sometimes I feel really gracious. Everything is really good, the world is so wonderful. It doesn’t last very long. I’m always pissed off at something again. It’s the best position for observing. You see all these groups get to the top, get too content and then blow it with bad music.” He gulps down the last of his coffee. “Our intention is to stay pissed off.”