Despite clocking a half century in the tricky business of rock, Cold Chisel is the powerhouse that keeps firing.

With six #1 albums on the ARIA Chart, including 2024’s 50 Years — The Best Of, and a national lap for which more than 225,000 tickets were sold, Chisel has lost none of its remarkable energy. Perhaps even more remarkable is the story of how Chisel blew apart a full lifetime ago, and reunited for 1997’s The Last Wave of Summer — the “hell freezes over” moment for Australian rock history.

Rewind to 1983, a time when New Wave was dominating the airwaves and every night out was constructed with hairspray. Cold Chisel was done.

The split wasn’t pretty. The band’s late drummer Steve Prestwich had been sacked after a disastrous German tour, and its members weren’t talking. Chisel’s dream of transplanting their remarkable Australian success overseas wasn’t realised. A decade of accelerated highs and brutal lows had taken their toll.

When it came, the split was actually a relief, co-founder Don Walker tells the LiSTNR podcast.

“The band was an unhappy place,” Walker recounts. “To say the least. I was angry about a lot of things. I didn’t think it had to be that way. I thought we should have been the biggest band in the world. I thought that had been sabotaged. It was an overwhelming relief for me to get away from it.”

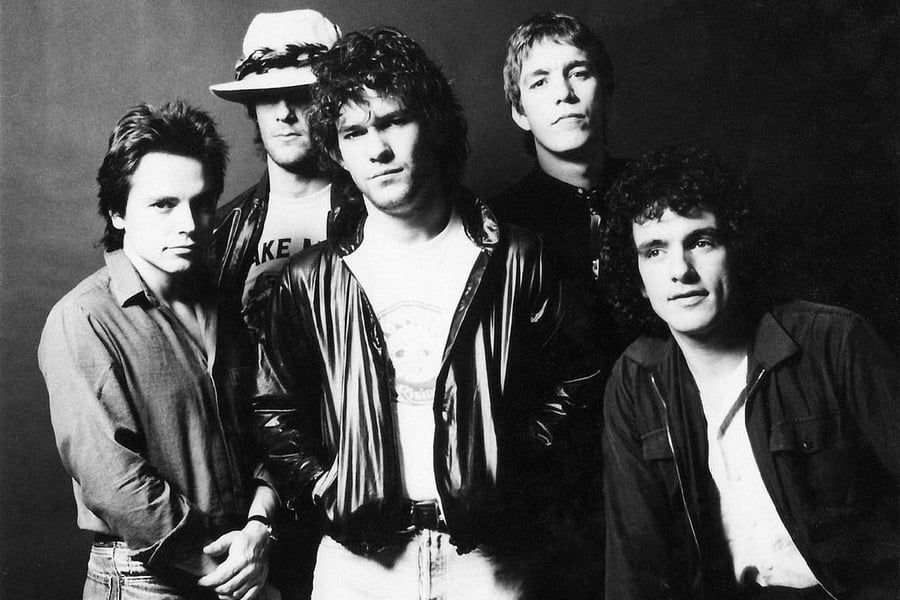

Cold Chisel

The rockers pushed ahead, releasing a final album – Twentieth Century – in August 1984.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Though Twentieth Century contained the classics “Saturday Night” and “Flame Trees,” the sessions were dysfunctional. Each member recorded their parts separately.

Chisel was operating on life support. “It was gone,” recalls Mark Opitz, one of the many producers who pieced the record together. “That was the last album by a long way.”

In the same month that “Flame Trees” was released as their final single, frontman Jimmy Barnes dropped his first solo effort, “No Second Prize”.

By September of that year, Barnes had scored his first #1 solo album, Bodyswerve. It was start of a second career as a solo superstar. With 21 leaders, including 15 as a solo artist, Barnes has more ARIA #1s than any other artist.

Chisel tour manager Mark Pope guided Barnes’ early solo career as manager.

“Jimmy’s one of those guys, in spite of everything, his work rate and his work ethic was friggin amazing,” Pope notes. “You know, he had the stamina of ten bulls. And he had (Michael) Gudinski behind him. And like you look at his career after Cold Chisel, I mean, how many artists get a second act in their lives? He not only got a second, he’s a living legend.”

While Jimmy dominated the charts as a solo artist, ex-Chisel manager Rod Willis was dedicated to keeping the band’s legacy alive. Knowing a new Barnsey solo album was coming out at Christmas, he’d often release a new Chisel compilation at the same time – and they’d share the chart spoils.

The other members of Cold Chisel would keep themselves busy in the ‘80s after the band imploded. Bassist Phil Small played with Pound. Prestwich joined Little River Band, fronted at the time by John Farnham; they’d record his Chisel ballad “When The War is Over”.

Ian Moss, who calls himself a “reluctant front man,” scored a solo #1 with the album Matchbook and ARIA Song of the Year “Tucker’s Daughter”. Walker wrote or co-wrote most of Matchbook. He’d then front his own band, Catfish, before forming Tex, Don and Charlie.

Even at the peak of their respective solo successes, Moss remembers Barnes planting seeds for a Chisel reunion.

“I do remember as early as 1988, Jim saying something like, ‘you know, if you ever want to get the band back together, I’m all ears’”, Moss says. “I don’t think I even took it in until after the phone call that that’s what he said. And then I realised his heart was still there… I learnt pretty quickly that Jim was always up for some kind of reunion. And I suspect a lot of that is to be back with the brothers kind of thing.”

Barnes remembers bringing up the topic on several occasions. “I’d go ‘come on guys let’s make a record’, and they’d all just be ‘nah nah’, and so I had sort of given up.” However, he continues, “there was a constant feeling of unfinished business. It was a constant feeling of, I miss my brothers. It was a constant feeling of, you know, maybe if things had gone differently, we could have still been playing.”

The early ‘90s were extreme for Barnes. Soul Deep became the most successful album of his career in 1991, but by June 1994 Barnes moved his family to France.

It came on the back of the Scotland-born singer being on the verge of bankruptcy – and being shadowed by media as he tried to work out how to pay his debts.

“I did a deal with the tax department and sold everything I had,” Barnes says. “Everything I’d worked for all my life I sold and it broke my heart,” he tells the LiSTNR podcast. “I didn’t flee the country, you know, with the tax department chasing me. I had Channel 7 chasing me, trying to get stories for their fucking news shows. There was so much of it going around that. It wasn’t funny to me, and it hurt.”

At a farewell party for Barnes, the singer had a quiet word to Willis.

“Everybody was back on speaking terms,” Willis explains. “Everybody was having a good time together. There was a dinner at a restaurant in King’s Cross. At the end when we’re all kissing and hugging, saying goodbye to each other. Jim came up to me and he said, ‘Are we ever going to get this band back together again?’ And I kind of looked at him said ‘Well, um it’s up to you Jim’. And he said to me, ‘No, Rod, it’s up to you’”.

Willis, who was managing Walker’s solo career at the time, knew the Chisel songwriter would be the key to any reunion. Walker, though, didn’t want to just reform for a nostalgia tour.

“If we were going to get back together it was going to be new music,” Walker says. “That was the thrill of it. There wouldn’t have been any thrill just getting back together and playing the hits, we were keen to get in the studio and do good music.”

By April 1997, Jimmy was back in Australia and Chisel were undertaking secret rehearsals in a room below the Sydney Opera House. “I just jumped down on the ferry and hopped over there every morning,” bassist Phil Small says. “There were playthroughs of certain songs and we tried out the new songs and ideas.” It was all looking “quite positive.”

After some serious negotiation, which almost saw the entire reunion cancelled, Chisel partnered with Mushroom Records in August 1997.

Their new music wouldn’t arrive for another year – with the band unable to settle on a producer or which of the countless new songs to record.

“When you start working together, it’s just natural, I think certain frictions pop their heads up,” Moss notes. “There’s shitty moments and a few arguments here and there. But what keeps winning every time is when we stop playing and everyone just loving the songs they’re playing and loving the way the other guys play.”

“There was a lot of enthusiasm to do it,” Willis says. “But there was also a bit of confusion about where to do it, who to do it with. I remember we went to a small studio in Sydney and certain members couldn’t work out where they were going to put their equipment….and I remember Jimmy getting really, really agitated about it. Like (this is) ‘bloody amateur hour’. And he was probably right to a degree, but I think it was being fueled as well by far too much chemicals. There were times in that period where I was very concerned about him and it’s not a very good time of his life. I know that for a fact and he’d openly admit it.”

Barnes has spoken openly about his struggles with alcohol and drugs, and how over the years his dependency on both deepened. During this Chisel reunion, Barnes would rock up fueled from the night before, barely able to stand up and sing. Then, he would refuel with whatever he had on him in the studio and leave rehearsals to go out to the club. Often, he’d roll up the next day still wearing the same clothes.

“I was pretty full on and I was pretty out of it and wild and had a death wish,” Barnes says. “I was like I was caught in a storm in a hurricane. But I’d get into the middle of Cold Chisel singing and that was the only time I felt comfortable. The only time I felt free. And the world would be falling apart around me and I’d get in there and bang. And it must have been painful for the guys to be around. I was like a Tasmanian devil, I just never stopped.”

The album, The Last Wave of Summer, was eventually released in October 1998 – reaching #1, one of the band’s half-dozen ARIA Chart leaders (their best-sellers include 1981’s Swingshift, 1982’s Circus Animals, and 2019’s Blood Moon).

The Last Wave was supported with a comeback tour – Chisel’s first since the iconic Last Stand tour of 1983. Despite dealing with his demons during recording, Barnes believes Cold Chisel made magic in the studio. He calls the Last Wave of Summer his favourite Chisel album.

“We came back and did a record that is one of the rawest, most gut wrenching Cold Chisel records that we ever made,” Barnes says. “It’s very organic, and there are bum guitar chords and wrong words sung and, and all that sort of stuff. But we’d say it’s got such a great feel, let’s just keep it. And I think that’s one of the groundbreaking things that happened to us making that record, we found out that the flaws, as in life, the flaws made the songs even better. The flaws made the songs even more poignant, more brutal, more accessible. It was a really great record. And it was a big learning curve for Cold Chisel.”

Looking back, Small remembers the difference between Jimmy in 1998 and sober Jimmy of today. “Back in the fuel days when he was being fuelled, you just had to tread warily because you just didn’t know which way it was going to go. But that’s completely gone and the vibe in the band is it’s the best it’s ever been. It’s fantastic.”

Barnes is twice inducted into the ARIA Hall of Fame. With Cold Chisel in 1993, and as a solo artist in 2005. “It’s like he’s born again,” admires Smalls. “He’s like was when I first met him. Top bloke, just a lovely guy.”

Cold Chisel’s best-of collection is currently the best-selling homegrown album on the ARIA Chart. Their “Big Five-O” tour rumbles on with three shows in New Zealand later this month.

Stream the five-part LiSTNR podcast here.