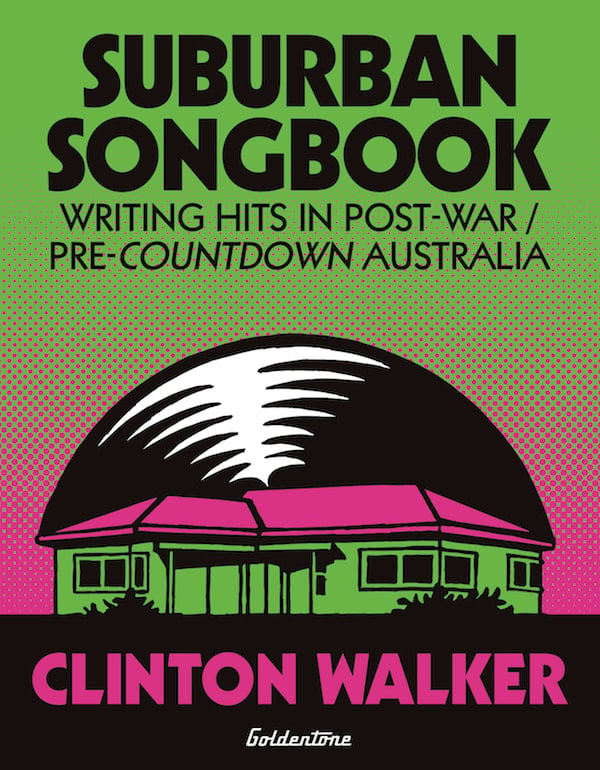

He’s previously been labelled “our best chronicler of Australian grass-roots culture”, and as Clinton Walker prepares to release his latest book, Suburban Songbook: Writing Hits in Post-War Pre-Countdown Australia, the author has shared an exclusive excerpt of his upcoming effort.

Set for release on November 1st, Suburban Songbook, gives readers a critical history of homegrown songwriting, and how its coming-of-age in the early ’70s helped to give Australian music its own voice – one that still resonates to this day.

His eleventh book, Walker takes the reader back on a trip 50 years back in time, looking at the period from when Australian music found itself transitioning from the “cover version culture in the ’50s and ’60s” to the era when original songwriting began to dominate, and both captured and evoked the “unique contours of life” in Australia.

In this exclusive excerpt from Suburban Songbook, Walker shines a light on the development of the female songwriting voice in local music, focusing on highly-influential (yet historically-overlooked) names such as Jeannie Lewis, Carol Lloyd, and Janie Conway, just to name a few.

Was Railroad Gin the first Australian band fronted by a woman – the late, great Carol Lloyd – who wrote or had a hand in writing the songs she was singing? For all the early ’70s advances in second-wave feminism that were notably driven by Australians (Germaine Greer with The Female Eunuch and Helen Reddy with “I Am Woman”, even if both had to go offshore to happen), girl singers tended to remain just that, girl singers. There were plenty of women on the Australian pop scene – most of them soloists like Allison Durbin, Alison MacCallum, Colleen Hewett, Renee Geyer, Marcie Jones, Kerrie Biddell, Linda George, Debbie Byrne – but none of them wrote the songs they sang and most of the songs they did sing were not Australian compositions either but covers sourced from overseas.

In this country, it was hard enough for male artists to push through with original songs from their own hand, let alone women or anyone else. Our first wave of rock ’n’ roll in the late ’50s was not predicated on original songs. In the ’60s, after the Bee Gees and the Easybeats showed the way, other acts like the Masters Apprentices, the Loved Ones and the Groop hit with strong original songs. The early ’70s, of course, was the real watershed/renaissance, when bands like Daddy Cool, Chain, Spectrum, Country Radio and so many others consistently turned out stunning original songs.

Not that women hadn’t occasionally broken out of the undergrowth. In fact, in the ’50s, it was the likes of Letty Katts, Dorothy Dodd, and Eula Parker who made greater advances than their male counterparts. Of course in country music there were always successful female songwriters like Joy McKean, Heather McKean, Shirley Thoms, Joan Ridgway and Lorna Barry, but in the pop field it was Queenslander Katts who hit with songs like “Riding the Never-Never” and “A Town Like Alice”, and Dodd and Parker who found success overseas long before any Australian men did, Parker with “Village of St. Bernadette”, which was a world-wide hit for Andy Williams in 1959, and Dodd with the lyrics for “Granada” and “Velvet Waters”, both of which became international standards oft-recorded.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Australian women had broken the mold of the classic girl group (usually a vocal trio or duo or maybe a sister-act) with self-contained bands in the ’60s like Brisbane’s Bluebeats, Melbourne’s Batgirls and the Vietnam-bound Vamps, in which women actually played the instruments! (but didn’t write the songs). At the same time, there were female singers who occasionally recorded local compositions (invariably written by men, or boys): the very young Barry Gibb gave songs to Noeleen Batley, Del Juliana and Lori Balmer, and of course Jay Justin and Joe Halford wrote “He’s My Blonde-Headed Stomp-Wompie Real Gone Surfer Boy” for Little Pattie; just as notable was a song Peter Pinne gave to Cheryl Grey for a 1967 B-Side, “Brand New Woman”, which was an assertive feminist statement of self-regeneration.

Not to mention Toni McCann’s “No”, written by Nat Kipner. Helene Grover wrote Noeleen Batley’s 1960 breakthrough hit “Barefoot Boy” and Elaine Goddard wrote Frank Ifield’s 1959 breakthough “True”, but if both these women were one-hit wonders, this was a syndrome that blighted male songwriters too (an immature industry’s inability to develop them), and certainly they did better than women like April Byron and Norma Stoneman, whose careers as singers and songwriters in the ’60s were tragically truncated due to industry immaturity and misogyny.

The legendary Wendy Saddington almost never sang original Australian songs, but when she did record Warren Morgan’s “Looking Through a Window” in 1971, it became the biggest hit of her career. It’s a slightly unfortunate irony that the first album made in Australia by a woman comprised entirely of songs written solely by her was by an American. Megan Sue Hicks had emigrated to Australia with her family in the late ’60s and was working at the Go-Set office in Sydney when Doug Rowe of The Flying Circus heard her sing a song she’d written, “Hey, Can You Come Out and Play” and offered to produce her if she could turn out the other ten or so songs required to make up an album. Only problem was, those other ten or so songs came nowhere near the quality of “Come Out and Play”. And then Hicks was deported.

A great singer like Jeannie Lewis strikes me as not a little unlike Gulliver Smith, a bravura talent but one whose sheer singularity made fully realising and selling her a hard task in an immature scene. But she is a towering figure, and her 1973 debut album on EMI, Free Fall Through Featherless Flight, might be the monolith or big bang where a feminist Australian pop began. “I Am Woman” was all right, but I tend to side with Renee Geyer on this one – she made a feature of James Brown’s “It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World” in her repertoire as a response, she always said, to what she saw as the banality of Helen Reddy’s supper-club anthem.

But there was nothing banal about Jeannie Lewis! Even moreso than Wendy Saddington, Lewis was an erstwhile jazz, folk and blues singer launched into the stratosphere, an artist possessed of a ferocious intensity and charisma, and Free Fall Through Featherless Flight might be as good an Australian album as the period produced, period.

Perhaps what was most remarkable about Free Fall was that it existed at all. The Australian music industry took some great strides in the early ’70s but it still had a long way to go. If Jeannie Lewis was no great songwriter herself – and I still wonder how much the emergence of women as songwriters in Australian music is a chicken and egg question – she gave voice to many great original songs in a way that even male solo stars from Johnny Farnham to Kamahl didn’t.

After she had enjoyed a starring role in Peter Sculthorpe’s 1969 “rock opera” Love 200, Free Fall was a cornucopia that pitted new Australian material alongside blues standards and even excerpts from Dylan Thomas and Carlos Castaneda! Not too numerous to mention are the Australian writers that Lewis bestows with her passion and purity of tone, from the aforementioned Gulliver Smith to her band’s MD, former-Tully keysman Michael Carlos, to Graham Lowndes and even Reg Livermore and (again) Peter Sculthorpe.

It’s like folk/rock/opera, the album a Folk-Rock Opera. On not acid but surely some sort of Light. Its centrepiece was a song called “Fasten Your Wings With Love”. It was the only track on the album that Lewis took a co-writing credit on, with pianist Jamie McKinley who played on the sessions, and it still remains a staggering five minutes of music. In it resides almost the entirety of Kate Bush’s oeuvre to follow! And yet like the whole album, full of breathtaking turns, it hangs together.

Lewis’s definitive version of “Till Time Brings Change”, by Graham Lowndes, is an epic ballad let down only by an unremarkable guitar solo. The sheer dynamics and breaks of “Fasten Your Wings With Love” lay bare a positive future for anyone willing to take the leap of faith and just fly. I love it. It was an anthem for a new age that sort of never came. I personally think it was a shame that subsequently so much of Lewis’s attention was given over to Latin American music and politics and to orthodox cabaret, but her star was a wandering and wondering one and her dedication to following the muse and not mammon cannot be faulted. Her legacy still shimmers.

A great singer like Alison MacCallum was privileged to have a few great songs written for her – like “I Ain’t Got the Time” by Murray Partridge, guitarist in her first band Freshwater, and “Superman” by Vanda/Young. Yet though they were minor hits, MacCallum was blighted by personal problems and faded from the scene.

Most Australian female singers blessed with ambition to match their pipes went overseas. Samantha Sang was a member of Australia’s “gumnut mafia” overseas and one who benefitted from original material by songwriters like the Gibb brothers and Brian Cadd. After leaving Australia and the stage name Cheryl Gray behind, including a discography that starred the terrific “Brand New Woman”, Samantha Sang (her real surname) arrived in London in the late ’60s and fell into the orbit of the Gibbs. Barry Gibb produced her in 1969 on a classic ballad he’d written for her, “The Love of a Woman”. She eventually hit all round the world in ’78 with a Barry Gibb song left out of Saturday Night Fever, “Emotion”. “Emotion” is a stone Australian classic. (And this is a measure of how the gumnut mafia worked: at the same time, other expatriates like Helen Reddy and Ray Burton were collaborating on “I Am Woman”, and John Farrar was writing and producing Olivia Newton-John, from “Have You Ever Been Mellow” to “You’re the One that I Want”…)

Renee Geyer’s albums started out comprising mostly American compositions, but by the time she formed her own Renee Geyer Band it was generating most of its own original material, most notably from the pen of guitarist Mark Punch. Renee remains adamant that her 1975 album Ready to Deal, which spawned the single “Heading in the Right Direction”, “is the best album I ever did,” due to its pure psychochemistry.

“It was a magic time,” she told me. “We created that album as a band; wrote it as a band, produced it as a band and it’s so original, for its time – so ahead of anybody else. I’m very proud of that record. It’s just a perfect example of like-minded musicians making music and having a flow throughout a whole record.” The only thing that surprises me about “Heading in the Right Direction” is that it didn’t score more covers by American soul singers beyond Bettye Swann’s version.

Polydor Records signed Brisbane band Railroad Gin complete with wild woman Carol Lloyd out front, and after the band served in the pit for the local iteration of the God-rock extravaganza Rock Mass for Love, gave it its head to record material largely written by MD Laurie Stone in collaboration with Lloyd. Perhaps the thing that prevented the Gin from making a bigger impact was not so much sexism – because they scored several Number Ones in their hometown of Brisbane, supposedly a bastion of redneck-dom – but the fact that they refused to move south and remained based in Brisbane, removed from the centre of pop things. But that can’t alter the classic status of their 1974 single “Matter of Time”.

A shift was starting to happen, incrementally. In 1972, Melbourne folk-country duo Carrl and Janie Myriad released a fine album called Of All the Wounded People… and it was half way there, with the couple sharing songwriting duties throughout. As Janie remembered in the liner notes she wrote for the 2014 reissue of the album, “In those days, women didn’t play electric guitar, especially not in the folk scene, whereas Carrl had begun as a guitarist and so the transition was easier for him. We wrote a lot of songs that were largely autobiographical and focussed on our life together.” Although it probably wasn’t fully appreciated until its reissue in 2014, Of All the Wounded People… is an album that sits well alongside its contemporaries like Country Radio, Flying Circus and The Dingoes.

It wasn’t till later in the ’70s, by which time punk rock had added its clarion call to the rising tide of feminism, that women in pop were able to overcome, if belatedly, the false hurdles that had held them back. After leaving Railroad Gin, Carol Lloyd went solo and immediately courted controversy with the cover of her album Mother Was Asleep at the Time, which pictured an unborn baby’s umbilical cord being cut by a pair of shears. But the album was good, maintaining the same level of intensity as the Gin and with Lloyd co-writing more strong songs like the sultry single “All the Good Things”. But ultimately her career would be cut short when she was cruelly struck down with a throat disease.

When Janie Conway reverted to her maiden name after divorcing husband Carrl Myriad, she got Stiletto together with singer Jane Clifton in 1976, initially to play a supper show at the Pram Factory. There were men in Stiletto right from the start (notably guitarist Andrew Bell), but the band was avowedly feminist and with a woman (Conway) driving it, playing guitar and writing songs, it really was a first for Australia. And after debuting at the Pram Factory, virtually an overnight sensation too.

“Stiletto rode a wave of popularity that was unprecedented for a band of its kind at the time,” Conway told Mark Sydow. “With its women-oriented lyrics and tough, loud, highly- arranged music” – call it ‘new wave’ – “we gained a strong following without really trying. We were simply in the right place and the right time.” Ross Wilson signed the band to a deal with his Oz label, but Conway had left long before the release of 1978’s Licence to Rage, the band’s one and only album. It would be fatuous to say that Conway coulda been a variation on something like Chrissie Hynde, but there, I just said it. But still some of Conway’s songs survived, with two co-compositions (with Andrew Bell) comprising both sides of one of the singles lifted from the album, “Goodbye Johnny” / “Woman in a Man’s World”.

Post-Stiletto, Janie Conway continued to write and perform, both with bands like Scarlet and as a solo artist, but by the time she had the systems in alignment to make a breakthrough (in other words, management, a record deal), she’d been pushing so hard for so long that she was also about to have a breakdown. By which time, the broom of punk rock was sweeping through music all round the world and opening up opportunities to female writers and instrumentalists.

Late-’70s woolly-jumper feminist folk outfits like Lavender Blues and The Ovarian Sisters didn’t have to be stacked up against the new young moderns of punk/post-punk to look somewhat antiquated. Even Robyn Archer looked a little old-hat, and besides, after her 1978 debut with two albums, The Ladies Choice and Wild Girl in the Heart, both of which contained all-original material and some good songs like “Menstruation Blues” and “Neurotica Suburbia”, Archer returned, not unlike Jeannie Lewis, to cabaret standards and seldom wrote for herself again.

The dam wall was finally starting to crumble and quickly pouring through came (punk/post-punk) acts like The XL Capris, Xero, Pel Mel, Divinyls, (Janie Conway’s) Scarlet, The Dugites, The Stray Dags, Flaming Hands, The Numbers, The Go-Betweens, The Electric Fans, The Electric Pandas, Toxic Shock, Dead Can Dance and Do-Re-Mi, showing what was (always) possible, and Australian music was becoming feminised and so much the better for it.

It’s just fortunate that Janie Conway survived at all, and after several decades during which she went back to university, became a (writing) teacher and then published a debut novel, in 2020 she returned, in a way, to where she’d left off her music, putting out a book and an accompanying album called Another Song About Love.

The book is an autobiographical novel in which Conway reflects on her interrupted music career. The album corresponds to or parallels the book as a soundtrack to it, with every song sharing a title with a chapter, some of them dating all the way back to the ’70s when Conway started turning out material that sadly struggled to find a niche. The album is poignant and swampy-bluesy, and not a lament for what might have been so much as a celebration of what still is. The book captures all the tropes that seem common to a woman’s lot in the game, or at least back-when, as Conway writes:

“Women singers sang high, their beautiful plaintive melodies allied with the pain of unrequited love, of heartbreak and unmarried pregnancy… There were no role models for women playing electric guitar in rock bands… I’ve never met a woman who owns a Stratocaster before… We were all beginners and we watched each other fiercely as we ploughed through songs from the latest American songbook… I want to be everything at once. I want to be a star. I want to be number one on the charts. I want, I want, I want… My mother plays in a band. Really? You must be very proud of her. Yep, she’s making a record… I adjusted my headphones, closed my eyes and took a deep breath… You wrote the song. You’re the one in control. Am I? I feel like everyone else is, not me… I rang the band to tell them I’d decided not to work for a while. The shell of my body could walk and talk but inside there was nothing left… Love killed the music, yet without it, I would never have sung a single song.”

Excerpted from Suburban Songbook: Writing Hits in Post-War Pre-Countdown Australia. Copyright © 2021.