The last time Serj Tankian saw Chris Cornell, everything seemed great. On March 25th, the two friends – Tankian, the singer in the alternative-metal band System of a Down, and Cornell, the founding singer-guitarist of the pioneering Seattle grunge band Soundgarden – were guests at a star-studded 70th-birthday gala thrown by Elton John in L.A.

“We had this long chat, sitting next to each other,” Tankian remembers. He and Cornell talked about composing for movies and the prospect of Cornell doing concerts with an orchestra. Tankian, about to go on the road with System of a Down, asked Cornell if he was tired of touring. “For myself, it’s fun but nothing new under the sun,” Tankian admits. Cornell “was just the opposite: ‘I’m really excited. I’m doing this tour with Soundgarden. I’ve got these other ideas.’ He had plans, man.”

Then on April 12th, Tankian and Cornell attended a red-carpet premiere in L.A. for The Promise, a historical drama about the Armenian genocide. Both men had recorded music for the film. “He was doing great, doing press – fighting the good fight” for the project, Tankian says. Cornell was “one of those guys,” he adds, who “tried to make everyone in the room feel comfortable with themselves. He was generous that way, with his emotions and time.”

Barely a month later, on May 17th, Soundgarden – Cornell, guitarist Kim Thayil, bassist Ben Shepherd and drummer Matt Cameron – played for 5,000 people at the Fox Theatre in Detroit. After the show, shortly past midnight, police officers responded to a call about an apparent suicide at the MGM Grand hotel and casino. They found Cornell in his room, on the bathroom floor, with an exercise band around his neck.

The singer, 52, was pronounced dead at the scene. In a statement issued on the afternoon of May 18th, the Wayne County medical examiner’s office confirmed Cornell’s death as suicide by hanging. Tankian’s response to the news: “Disbelief,” he says, speaking just over 24 hours later. “I’m like, ‘No fucking way.’ ”

There were certainly no warning signs on April 19th, when Cornell performed “The Promise,” his theme song for the film, on The Tonight Show with Cameron, a string section and record producer Brendan O’Brien on guitar. Cornell and O’Brien had worked together in the -studio since the mid-Nineties, when the latter mixed Soundgarden’s 1994 multi-platinum breakthrough, Superunknown. O’Brien produced Cornell’s latest solo album, 2015’s Higher Truth, and had recently done sessions with Cornell for a potential record of cover versions.

“He didn’t seem any different to me,” O’Brien says of Cornell’s mood at The Tonight Show. “I felt like we had a good time there. He was in good spirits.” O’Brien notes that the volume on his guitar was mistakenly cranked up during the taping. “The next day I sent an e-mail: ‘You sang great. Sorry about being so loud.’ And he was, ‘All great. Love you. No worries.’ ”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Guitarist Tom Morello played with Cornell between 2001 and 2007, when Cornell formed Audioslave with Morello, drummer Brad Wilk and bassist Tim Commerford, the instrumental backbone of Rage Against the Machine. Morello last saw Cornell on January 20th, when Audioslave reunited in L.A. at the Anti-Inaugural Ball, a protest concert held on the night of President Trump’s inauguration.

Cornell was “shining” at that gig, Morello insists. “We hung out after the show – just laughed, took pictures. The last thing he said to me was, ‘I had such a great time. I would love to do this again. You just let me know.’ I was like, ‘Yeah, let’s figure it out!’

“It’s unbelievable,” Morello says of Cornell’s death. “I don’t know what the phases of mourning are, but I’m in the first one. I still expect this to be some kind of mistake” – that Cornell will soon be in touch with a text or phone call “where it’s ‘I’m cool. I’m so sorry. That was a scare. Everything is going to be all right.’ ”

Audioslave in concert at Roseland Ballroom in New York City on April 30th, 2005.

At 7:06 P.M. on May 17th, after pulling into Detroit for Soundgarden’s show, Cornell fired off a jubilant message on Twitter – “Finally back to Rock City!!!!” – with a photo of the band’s name on the Fox Theatre marquee. Four hours later, Cornell finished the encore as he frequently did, closing an epic version of “Slaves & Bulldozers,” from Soundgarden’s 1991 album, Badmotorfinger, with a bellowing-vocal flourish of Led Zeppelin’s “In My Time of Dying.”

The rest of the 20-song set list ran the full length of Cornell’s progressive-metal legacy with Soundgarden, from the angular-hardcore fury of their 1987 debut 45, “Hunted Down,” to 2012’s King Animal, the band’s triumphant studio comeback after more than a decade’s hiatus. Soundgarden also played nearly half of Superunknown, their bestselling album and – in the dark, psychedelic adventure and lacerating self-examination of the hits “Fell on Black Days” and “Black Hole Sun” – Cornell’s personal quantum leap as a songwriter.

Cellphone footage from Cornell’s final concert is troubling but inconclusive. In Detroit, his between-song raps veer from grateful to cryptic, including a bizarre reference to crosses burning on lawns. At times, his singing – at its best a dramatic tension of vintage rock-lord howl, bluesy melodic poise and seething, syrupy menace – sounds too far off the beat, lagging behind the band. And in that encore, Cornell punches the air with triumph – before turning his back to the crowd as he and Thayil face their guitar amps, unleashing a last firestorm of feedback.

After signing some autographs outside the Fox, Cornell went to his hotel room, where he spoke to his wife, Vicky, on the phone. “I noticed he was slurring his words; he was different,” she said in a statement issued May 19th. “When he told me he may have taken an extra Ativan or two, I contacted security and asked that they check on him.” Soundgarden bodyguard Martin Kirsten kicked in the hotel-room and bedroom doors – both were locked – and found Cornell “with blood running from his mouth and a red exercise band around [his] neck,” according to a police report.

Cornell had a prescription for Ativan, an anxiety medication that has been used by recovering addicts. Adverse reactions, especially in higher doses, include drowsiness, mood swings, confusion and thoughts of suicide. In a 1994 Rolling Stone interview, Cornell confessed to being “a daily drug user at 13” and quitting at 14. But there were subsequent battles with alcohol and substance abuse, which led Cornell to check himself into rehab in 2002. Tankian attests to Cornell’s sobriety in recent weeks: At the Elton John party, Cornell joined in a champagne toast – raising his glass – but did not drink.

Chris Cornell and family attend New York screening of ‘The Promise’ at the Paris Theatre on April 18th, 2017 in New York City.

Chris Cornell and family attend New York screening of ‘The Promise’ at the Paris Theatre on April 18th, 2017 in New York City.The surviving members of Soundgarden declined to speak for this story. A full autopsy and toxicology report had not been released as Rolling Stone went to press. But in the May 19th statement, Vicky Cornell and family attorney Kirk Pasich disputed the verdict of suicide. Chris “may have taken more Ativan than recommended dosages,” Pasich said. But, Vicky said, “I know that he loved our children” – the couple had a son and a daughter, Christopher and Toni – and “would not hurt them by intentionally taking his own life.” Chris also had a daughter, Lily, from his previous marriage to former Soundgarden manager Susan Silver. They divorced in 2004.

Until that Wednesday in Detroit, Cornell was “the last guy in the world I thought that would happen to,” says guitarist Jerry Cantrell of the Seattle band Alice in Chains, who lost their original singer, Layne Staley, to a drug overdose in 2002. “That’s not the way that book was supposed to end. And it was not the way that book was going.”

In and beyond Seattle, Cornell was a widely respected native son: an elder statesman and charter survivor of the city’s pregrunge underground in the Eighties – he and Thayil started Soundgarden as a trio in 1984 – and its turbulent commercial boom in the wake of Nirvana’s 1991 smash, Nevermind. Dave Grohl recalls being struck by the contrast between Soundgarden’s roaring futurism and Cornell’s thoughtful, soft-spoken manner offstage the first time they met, at a party at Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic’s house. “There was a bunch of the Seattle gang there,” Grohl says, “and Chris just seemed so quiet and mellow compared to the rest of the maniacs.”

But Cornell was frank and fearless in his songwriting, addressing the lessons in loss that repeatedly shook him and his hometown. In March 1990, Andrew Wood, the singer in Mother Love Bone and Cornell’s former roommate, died of a heroin overdose. The death would continue to haunt Cornell through the years. He soon wrote a pair of thundering memorials to Wood, “Say Hello 2 Heaven” and “Reach Down,” that became the cornerstone songs for 1991’s Temple of the Dog, a Top Five collaboration with members of the then-unknown Pearl Jam.

Wood also figured in “Like Suicide,” a Superunknown track that took on more weight and healing with the 1994 suicide of Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain, a month after that album’s release. “The emotional possibilities” on that record “were now emotional realities,” Cornell said in 2013, looking back at his own interior war of feelings in songs such as “Let Me Drown” and “Limo Wreck.” He described “Like Suicide” as “about all of these beautiful lives around us, twice as bright and half as long, careening into walls.” But, Cornell went on, “after the funerals, we feel better about ourselves when we’re able to get up the next day.”

Cornell was candid, in interviews as well as his lyrics, about the allure of the abyss. Part of it, he once said, came from “growing up in the Northwest. You’re always moving between the creepiness of everyday life and this natural beauty that surrounds you all the time.” In a striking 1999 exchange with Rolling Stone, Cornell admitted to a habit – “something I’ve done since I was a kid” – of opening windows and imagining what it would be like to jump. “But I never take it seriously,” he added right away.

“I always felt like Chris had a lonely place inside of him that he went to creatively,” says filmmaker and veteran Rolling Stone writer Cameron Crowe, who gave Cornell a cameo as himself in Singles, Crowe’s 1992 romantic drama set in the erupting Seattle scene. “Sometimes he laughed at the whole rock-god thing, like [in the Soundgarden song] ‘Big Dumb Sex.’ He had that thing: ‘I know how to mock this.’

“Chris had the right attitude to survive,” says friend Cameron Crowe. “I never thought he’d go all the way into the dark place.”

“I never thought Chris – given family and a certain sunniness, the humor and soulfulness in the way he talked about his life privately – would go all the way into the dark place,” Crowe says. “I thought he would access it, write about it and mock it too well.”

Tankian points out that “The Promise,” the last song Cornell released before his death, “is about survival – to survive and thrive. . . . I’ve seen people in a bad place. You wish they would find a way to the light and find peace with themselves.” Cornell, Tankian insists, “wasn’t that guy. He was gracious, standing in the light.”

Until Detroit.

Cornell performing at his last show in Detroit on May 17th, 2017.

Cornell was born Christopher John Boyle in Seattle on July 20th, 1964, the fourth of six children. His father, Ed, was a pharmacist; his mother, Karen, was an accountant. Chris dropped out of school at 14, after his parents’ divorce (Cornell is Karen’s maiden name), and worked in a seafood warehouse and as a cook. Cornell also turned to music for release, starting on drums at 16. His first favorite band was the Beatles; Cornell later described the diversity of texture and attack on Superunknown as Soundgarden’s “White Album period.”

In the early Eighties, Cornell played in a covers band, the Shemps, that at different times included Thayil and founding Soundgarden bassist Hiro Yamamoto. “When I met Chris,” Thayil said in 1992, “my first impression was that he was some guy who had just got out of the Navy or something. He had real short hair and was dressed real slick.” Cornell also “had a great voice.”

In 1984, the three started Soundgarden, minting a unique heavy metal that combined the hypersurreality of hardcore bands like Minutemen and Meat Puppets with the British post-punk existentialism of Wire and Joy Division. Shepherd, who became Soundgarden’s bassist in 1990, was already a fan; he saw the original trio’s second gig, opening for Hüsker Dü. “They didn’t play the usual punk rock,” he said in 2013. “And they weren’t butt rock or heavy metal, the way people tried to label them later because they had long hair. To me, the music was black, blue and overcast with lightning.” Cameron joined in 1986, after Cornell – who also played guitar and was emerging as the dominant songwriter – became Soundgarden’s full-time frontman.

“Soundgarden took the riff rock I love and made it smart,” Morello says, recalling that band’s profound impact on the early sound and direction of Rage Against the Machine. “Cornell’s dark, poetic intellect was not something you found in heavy metal.”

Grohl vividly remembers the first time he saw Soundgarden live – before he immigrated to Seattle, at a Baltimore club in 1990. “It was as if all of our punk-rock and classic-rock dreams came true together,” Grohl says. “Everybody, whether it was in Washington, D.C., or Washington state, looked up to Soundgarden as this force of nature.”

The first band to release a 45 with the iconic Sub Pop Records and the first act from the Seattle underground to snare a major-label deal, Soundgarden were “a beacon to follow,” Cantrell says, for the local groups in their wake. “Our town’s not that big. Everybody kept an eye on what those guys were doing. And it was inspiring.” For a time, Alice in Chains shared management with Soundgarden. “We loaned each other money so our bands could tour,” Cantrell explains. “We had the same T-shirt guy. It was all intimate shit.”

Chris Cornell of Soundgarden during RIP! Magazine party in Hollywood, California.

Cornell, in particular, represented “a strong strain running through our whole town – he was always so honest, from the moment I met him,” Cantrell says. “I share a lot of the issues Chris communicated” in his songwriting. “And there’s a power in sharing your weakness with the people who need to hear that, so they can consider, ‘Fuck, that guy’s dealing with it.’ You don’t feel so alone.”

“Great art comes from generosity,” Pearl Jam guitarist Stone Gossard said last year, recalling the genesis of Temple of the Dog. Gossard and Pearl Jam bassist Jeff Ament, who played in Mother Love Bone, were devastated by Wood’s death. Cornell wrote the songs for Temple of the Dog “from as pure a place as you can find,” Gossard continued. “And then he reached out, letting us in.”

Gossard, Ament and Pearl Jam guitarist Mike McCready became Cornell’s core band in Temple of the Dog with Soundgarden’s Cameron. Cornell also took a paternal interest in Pearl Jam’s singer, a recent San Diego emigré named Eddie Vedder. “Ed was super-shy back then – we were just getting to know him,” McCready said in 2016. At one Temple of the Dog session, Cornell brought in a new song called “Hunger Strike.” As he ran down the arrangement, Vedder jumped in, taking the lower melody against Cornell’s soaring vocal.

“Suddenly, it was a real song,” Cornell later remarked. “Hunger Strike” became Temple of the Dog’s breakout single; it was also Vedder’s first featured vocal on a record. “Chris’ heart was big enough,” McCready said, “to let him do it.”

Soundgarden broke up in 1997, overwhelmed by internal tensions and private trials; Cameron soon joined Pearl Jam. Cornell later acknowledged that he was drinking heavily “to get through things in my personal life” (his first marriage was dissolving in acrimony) – and “a pioneer,” he noted ruefully, in abusing OxyContin.

“It was the most difficult part of my life – I’m lucky I got through it,” Cornell conceded in 2009. “I’m not sure if it was the best place for me,” he added, referring to rehab. “But it worked.”

Timbaland and Chris Cornell appear in the Verizon Mobile Recording Studio Bus on March 13th, 2009 in Chicago.

‘I spent the last week and a half in a room with no windows, just doing Soundgarden demos,” Cornell told me during an interview for Rolling Stone in August 2015. “We’re going to meet in four days and spend a week together. By the end of that week, we’ll have a lot of stuff, a lot of ideas to work with.”

That month, Cornell was also preparing for the release of his fifth solo album, Higher Truth, and fall concerts – the latest leg of his Songbook Tour, a one-man evening of new material, greatest hits, surprising covers and relaxed storytelling, launched in 2011. “Now, I kind of get Neil Young,” he admitted. “He goes on tour with Crazy Horse, then he’s out with Booker T. and the MG’s. Then he’s on tour by himself with seven guitars. It makes sense to me now. He’s not trying to find out who he is.”

Young is, I suggested, all of those things. “And all of those things,” Cornell replied, “are me.”

Thayil confirmed to Rolling Stone last year that Soundgarden were still inching their way to a new studio album, their first since King Animal, while touring and pursuing a campaign of deluxe archival projects. Expanded editions of Badmotorfinger and Soundgarden’s first full-length album, 1988’s Ultramega OK, have come out in recent months. Cornell, on his own, had started recording the covers album with O’Brien. And Paul Buckmaster, who created the string arrangement for “The Promise,” says that Cornell was “great in the studio” and “totally fascinated” with the process of recording with an orchestra: “He’d never seen anything like this before.” Buckmaster reveals that the 2016 session for the film song went so well that, in recent weeks, “there was even talk of me doing orchestrations” of Soundgarden material for live shows, possibly with the band.

In recent years, Cornell “seemed to be on a mission to work all the time,” O’Brien says. “And I mean all the time. He always seemed to be doing something – and a lot of different things. Chris was also a guy,” O’Brien adds, “who liked being someone who was on their game. He liked people to see him that way.”

There were misfires. Cornell’s 2009 album, Scream, made with the hip-hop producer Timbaland, was the singer’s first Top 10 solo effort but was savaged in the press – and by some peers. “Seeing Chris do that record felt like a blow to me,” says Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails. “I thought, ‘He’s above that, man. He’s one of the 10 best vocalists of our time.’ ”

Reznor went public, blasting Cornell on Twitter – “which,” the former says now, “I immediately regretted.” Five years later, as Soundgarden and Nine Inch Nails were about to start a co-headlining tour, Reznor wrote Cornell an e-mail, apologising for that outburst. “He was very cool and generous about it – ‘It’s the past, fuck it. Let’s go on.’ The Chris I met on that tour was a gentleman that completely had his shit together.”

Cornell lived at various times in Los Angeles, Paris and Miami. But he always had time for Seattle. In January 2015, Cornell was part of a small army of local heroes – including Guns N’ Roses bassist Duff McKagan and members of Pearl Jam – at the city’s Benaroya Hall for a tribute concert to Mad Season, a short-lived mid-Nineties group fronted by Staley and McCready. Cornell personally asked Alice in Chains drummer Sean Kinney to join the show.

“I wasn’t thinking I could be able to handle it,” Kinney says, alluding to the continuing hurt of Staley’s death. “But Chris really coaxed me to come out. I went as far as rocking the bongo,” he notes, laughing. “And it was a beautiful thing. He told me how he had to get into it, how hard it was for him. And I just told him, ‘Layne would have loved the shit out of it.’

“I have a lot of experience with what’s going on here,” Kinney says of Cornell’s passing. “Every time they write about your band from now on, it will always be there: ‘X died.’ I just go to the music and what’s left. We’re lucky that we have that.”

“There’s going to be people that are going to mythologize this – ‘the grunge curse,’ ” Tankian says. “I wouldn’t do that.” Cornell “was 52 years old. He made it through the woods of whatever he was suffering with his life – his youth and later.”

“He was open about being vulnerable,” Crowe points out, “with a certain amount of pride that he had been able to make it through tough times. I never had a conversation with him where he said, ‘I’m lost.’ It was always, ‘I had a tough period, but I’m having fun now.’ ”

Cornell “always had it, the same thing as when I saw Layne for the first time – the commitment to take that ride,” Cantrell says. “There was something that I recognised and aspired to – to have your own voice and sound. Nobody else sounds like that guy. Nobody will.

“There is a space now and forever empty because of that,” Cantrell says of Cornell’s death. “It’s never going to make sense. It’s never going to feel right. And it’s always going to hurt.”

—

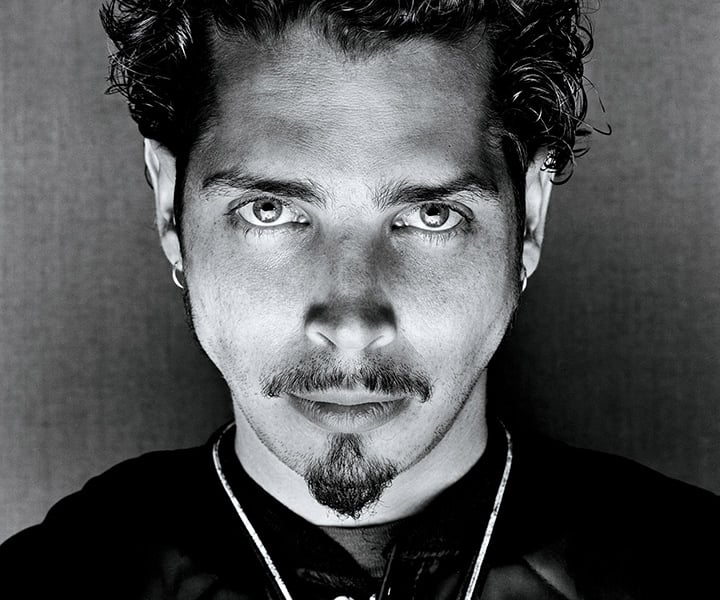

Additional reporting by Kory Grow and Ashley Zlatopolsky. Top photo, credit: Mark Seliger.