Burt Bacharach, the composer and bandleader whose elegant melodies dominated pop radio for several decades, has died at the age of 94.

Bacharach’s publicist, Tina Brausam, confirmed to the Associated Press that the songwriter died of natural causes on Wednesday at his home in Los Angeles.

During his 1960s heyday, Bacharach — along with his earliest and most productive partner, lyricist Hal David — wrote songs that became hits and, later, timeless standards. Among their many classics were “(They Long to Be) Close to You,” “I Say a Little Prayer,” “The Look of Love,” “Walk on By,” “Always Something There to Remind Me,” and “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head.”

Raised on jazz and classical and not rock and roll, Bacharach brought a level of melodic sophistication and romanticism — unconventional 5/4 time signatures and melodies that didn’t stick to standard iambic pentameter — into the Top 40. “Odd bar lines, odd time signatures, things that musicians couldn’t play in the studio when we were recording,” Bacharach said in 1979. “I was always swimming upstream, breaking rules.”

The songs, wrote one critic in 1968, were “too old for the marijuana generation and too young for remedial jogging,” yet the Bacharach-David juggernaut (and later Bacharach songs co-written with his wife, songwriter Carole Bayer Sager) easily slid onto the radio and impacted later songwriters like Elvis Costello. “He’s probably one of the rare composers of pop music that have a language of their own,” Costello once said of Bacharach. “They favor certain harmonies and intervals heavily, and certain voicings and you realize these things belong to them. It’s their style.”

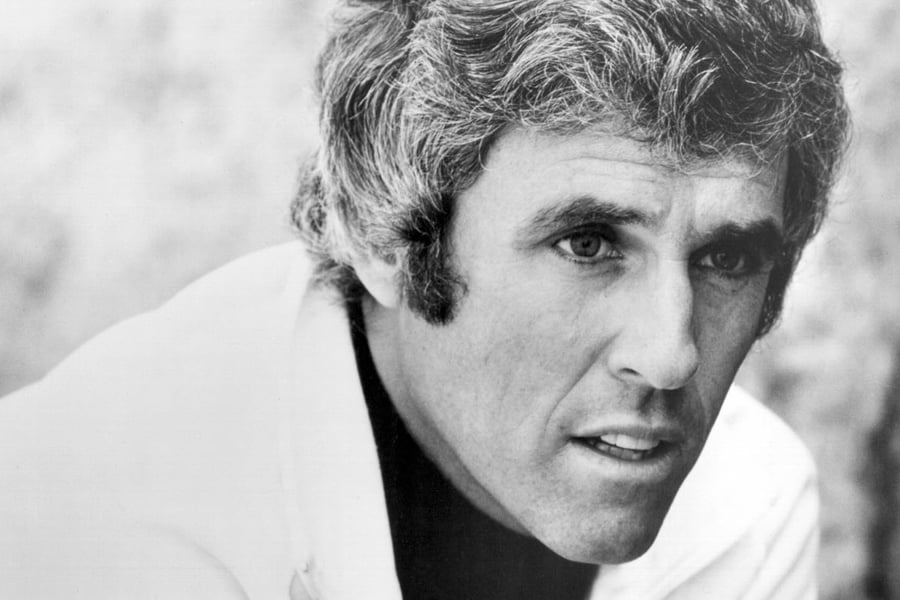

Bacharach wasn’t merely a behind-the-scenes player, though. With his rugged good looks and blue eyes, he became a known brand himself, recording albums on his own (with instrumental versions of his hits) and marrying actress Angie Dickinson in 1965.

Born May 12, 1928, in Kansas City, Missouri, Bacharach was the son of newspaper columnist Bert Bacharach and artist and songwriter Irma Freeman. Thanks to his father’s job, Bacharach moved to Forest Hills, New York, later admitting to wanting to be an athlete who ”hated” taking piano lessons, which his mother demanded. But after hearing Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloe suite and sneaking into jazz clubs in Manhattan with a fake ID to see Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis, his career choice was cemented. “Hearing them,” he said in 1998 of that jazz acts, “it was like a window opening.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Bacharach enrolled in McGill University in Canada, where he studied music and wrote his first song (“The Night Plane to Heaven”); he also studied at the Mannes School of Music in New York. In 1950, Bacharach began a two-year stint in the Army, playing piano at army bases and serving as a bandleader and accompanist. His professional career began in earnest after his military years when he landed work as an arranger and pianist for MOR pop singers like Steve Lawrence and Vic Damone. Starting in 1958, he became bandleader and conductor for the reclusive actress and singer Marlene Dietrich, a role that lasted on and off for six years.

Right before his Dietrich stint, in 1957, Bacharach met David, an established, soft-spoken lyricist seven years his senior, and the two began writing songs together. “You could go and play a song for one publisher,” Bacharach recalls, “and then he’d say, ‘I don’t like it,’ and then you’d go down the hall.” The two cranked out numerous songs before finally hitting the charts with “The Story of My Life” (for Marty Robbins, 1957) and “Magic Moments” (for Perry Como, 1958). In 1961, Bacharach scored his biggest pop hit to that time with “Baby, It’s You,” cut by the Shirelles and co-written with Mack David and Luther Dixon.

While working with the Drifters, Bacharach met a Jersey-born gospel and pop singer, Dionne Warwick (then Warrick), who was part of a female backup group supporting the Drifters. “After the first rehearsal, Burt approached me and asked me if I could do some demonstration records of songs he was writing,” Warwick said later.

“Right from the first time I ever saw Dionne, I thought she had a very special kind of grace and elegance,” Bacharach said in 2013. “She had really high cheekbones and long legs, and she was wearing sneakers, and her hair was in pigtails. The more Hal and I worked with her, the more we saw what she could do. Dionne could sing that high, and she could sing that low.”

Those demos made their way to Scepter Records, which signed Warwick, and her first single with Bacharach and David, “Don’t Make Me Over,” marked the beginning of a remarkable union of Warwick’s supple voice, Bacharach’s complex melodies and David’s conversational lyrics.

Following his death, Warwick said Bacharach’s death hurt like losing a member of her family.

“Burt’s transition is like losing a family member. These words I’ve been asked to write are being written with sadness over the loss of my Dear Friend and my Musical Partner,” Warwick said in a tribute. “On the lighter side we laughed a lot and had our run-ins, but always found a way to let each other know our family, like roots, were the most important part of our relationship.”

Warwick added, “My heartfelt condolences go out to his family, letting them know he is now peacefully resting and I too will miss him.”

Later singles like the frisky “I Say a Little Prayer” and the bossa-nova-inspired “Walk on By” both hit the top 10. But those were only a few of the glorious pop records that emerged from that trio, which also included “Anyone Who Had a Heart,” “Message to Michael,” “Do You Know the Way to San Jose,” “Promises, Promises,” “Alfie,” “I Just Don’t Know What to Do with Myself” and “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” which all hit the Top 40 or Top 10. (Bacharach said he preferred Aretha Franklin’s version of “I Say a Little Prayer,” though.)

That barrage of hits — each one a perfectly crafted, sublime pop single — would have cemented Bachrach’s legacy alone. But during that same era, he and David also found themselves on the charts by way of B.J. Thomas (“Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head”), Herb Albert (“This Guy’s in Love With You”), the Carpenters (“[They Long to Be] Close to You”), Dusty Springfield (“The Look of Love”), Jackie DeShannon (“What the World Needs Now Is Love”), and the Fifth Dimension (“One Less Bell to Answer”).

Bacharach’s songs went against the rock and roll grain at the time, but he didn’t seem to care. “If a song like ‘Alfie’ can make it on both sides,” he said in 1968, “that is a great satisfaction. You have real adults buying it … My mother and father wouldn’t even think of turning it off. And kids [age] 14 buy it, too. Great.”

By the mid-Seventies, Bacharach’s streak ended. He and David had a falling out during the making of Lost Horizon, a big-budget remake that included their songs when Bacharach demanded that he get a larger split of their royalties. (“Fuck you and the fuck the picture,” he famously told David.) The movie’s failure at the box office also impacted Bacharach. “I just wanted to get out of town,” he told NPR’s Terry Gross. “I wanted to go down to Del Mar and hide, you know, and not write and just play tennis every day. But my attorney told me, ‘Hey, you know, you’re going to get in trouble with your commitment with Hal to write for Dionne.’ And I just ignored his advice – very bad. So as far as responsibility and blame, it’s all on me, you know.” Warwick also sued Bacharach and David for failing to record additional albums with her.

The rise of disco and punk made Bacharach’s elegant song-craft feel like a relic from another time. But gradually, Bacharach came back with the help of new collaborators. With lyricist and singer Carole Bayer Sager, whom he would marry in 1982, he returned to the charts with Christopher Cross’ “Arthur’s Theme (Best That You Can Do),” which hit no. 1 and won the Oscar for best song, followed by hits for Warwick and an all-star cast (“That’s What Friends Are For,” whose sales benefited AIDS research), Neil Diamond’s “Heartlight,” and Patti Labelle and Michael McDonald’s “On My Own.”

Starting in the Nineties, Bacharach began being newly appreciated. He collaborated with Costello on “God Give Me Strength” (for the 1996 movie Grace of My Heart, based on the story on the Brill Building) and then on an entire album together, Painted from Memory, two years later. (Costello later said that playing his early demo of “God Give Me Strength” to Bacharach was “probably one of the most nerve-wracking songs I’ve ever had to do.”) Noel Gallagher admitted that Oasis’ “Half the World Away” was direly inspired by “This Guy’s in Love With You.” Bachrach’s 2005 album At This Time included collaborations with Costello, Dr. Dre, and Rufus Wainwright. In 2012, he was awarded the Library of Congress Gershwin Prize by then-president Barack Obama. In 2020, he signed a lucrative publishing deal with Primary Wave.

His marriage to Dickinson ended in divorce in 1980, as did his marriage to Bayer Sager in 1991. Nikki, his daughter from his marriage to Dickinson, suffered from health and mental issues and died by suicide in 2007. Hal David died in 2012.

“All those so-called abnormalities seemed perfectly normal to me,” Bacharach said in the liner notes to a 1998 box set. “In the beginning, the A&R guys would say, ‘You can’t dance to it’ or ‘That bar of three needs to be change to a bar of four.’ … I listened and ended up ruining some good songs. I’ve always believed if it’s a good tune, people will find a way to move to it.”

“Very sad day, probably one of the most influential songwriters of our time. He was a great inspiration . Rest in peace Burt Bacharach,” the Kinks’ Dave Davies tweeted Thursday.

Kiss’ Paul Stanley wrote, “Burt Bacharach… What a loss but what a treasure of amazing songs he’s left us. His work with Hal David, Carole Bayer Sager and others, share an effortless combination of simplicity & sophistication. Walk On By? That’s What Friends Are For? Alfie? This Guy’s In Love With You? WOW.”

“The Songwriting world has lost its Beethoven today. Compose in Power forever Burt Bacharach,” songwriter Diane Warren tweeted.

From Rolling Stone US