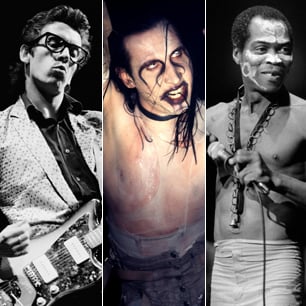

15 Rock & Roll Rebels

For these 15 revolutionaries, the only place to be was on the outside looking in.

Deep down, the bad boys are quite often the sensitive ones – the ones who feel the world’s pain. They don’t “do what everybody else does” because they don’t understand why things have to be that way. And they often welcome the ostracism they get in return: “If you’ve got a blacklist, I want to be on it,” as the socially conscious songwriter (and major Clash fan) Billy Bragg once sang. Here are 15 true revolutionaries, for whom the only place to be was on the outside looking in.

[Editor’s Note: A version of this list was originally published June 3, 2013]