No Apologies: All 102 Nirvana Songs Ranked

RS tackles the complete catalog of the band that defined the Nineties and made the world a lot noisier

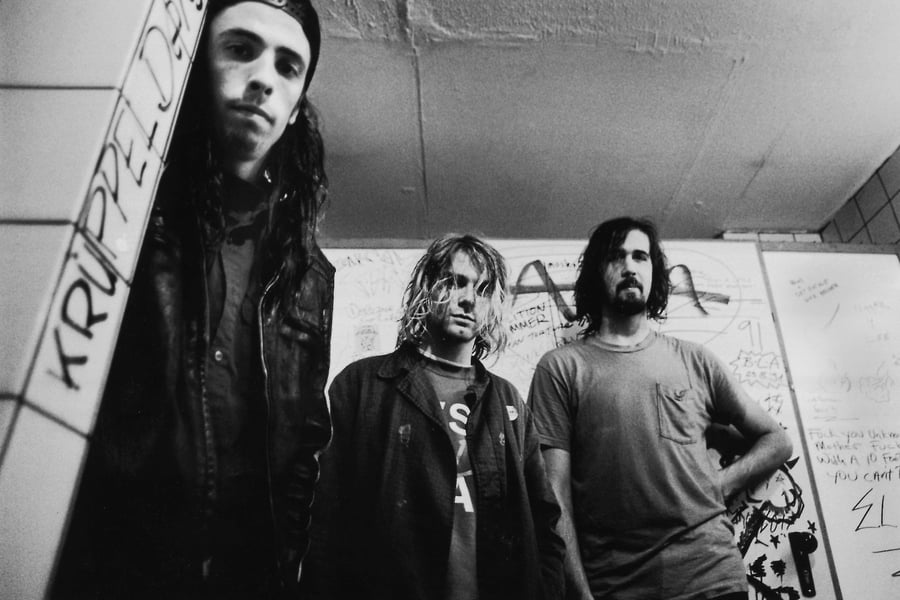

Paul Bergen/Redferns

We’ve dug deep into the catalog of the chaos-embracing sludge-pop titans who changed the world and tackled a massive task: ranking all 102 album cuts, B-sides, bonus tracks, officially released covers, bootlegger-traded originals, home demos, Peel Sessions, and 4-track experiments we could find, from Nirvana‘s formation in 1987 to their McCartney-assisted reunion in 2013. It’s no secret that the 38 songs on Nirvana’s three classic albums blurred the lines between punk’s most subterranean muck and pop’s highest reaches. But they also left behind a wealth of other material from the shaggy to sublime, from combustible to calm, from coulda-been hits to unfinished sketches. Here it is, from Aero to Zeppelin, and everything in between. (Listen to the full playlist on YouTube here.)

From Rolling Stone US