Jerry Garcia’s 50 Greatest Songs

From country-rock gems to exploratory jams, from Grateful Dead classics to solo high-points, here’s the ultimate guide to an epic musical life

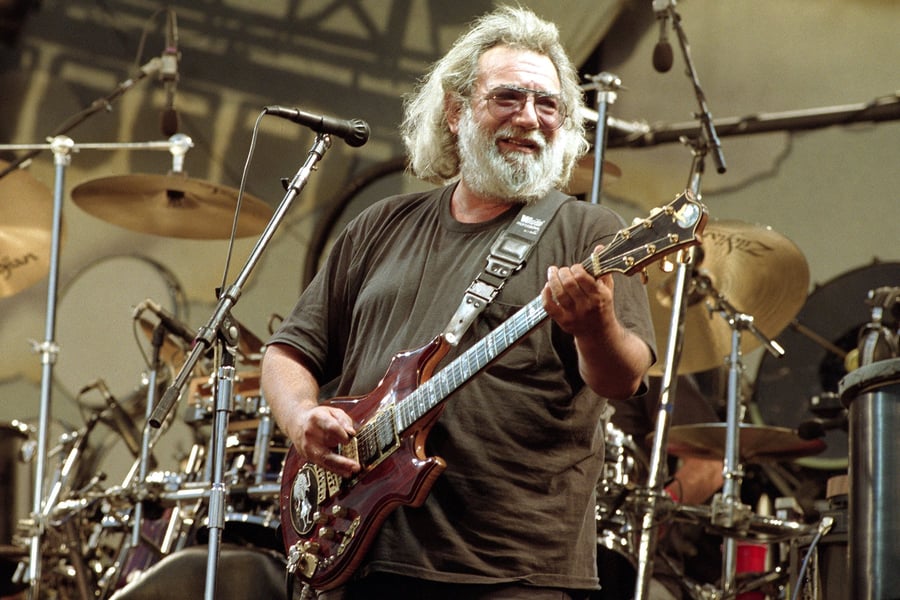

Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead performs at Cal Expo Amphitheatre on August 14, 1991 in Sacramento, California.

Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

Related: Grateful Dead Ultimate Album Guide

Just as the Grateful Dead were more than just a “jam band,” Jerry Garcia was more than just the affable Captain Trips of the scene. Over the roughly 35 years that he wrote and recorded songs with the Dead and on his own, Garcia was an uncommonly eclectic musician — equally at home with folk, bluegrass, electronic music, old-timey ballads, country, reggae, and Chuck Berry-style rock & roll. Nor was he simply “Jolly Jerry,” as his longtime lyrical collaborator, Robert Hunter, told Rolling Stone in a 2015 interview. “That man had an agony almost that he had to fight,” Hunter said. “I suppose it had something to do with losing his dad so young, and possibly his finger getting chopped off. Who knows, but there was a decided darkness to him. But you know, what great man doesn’t have that? His bright side, his ebullient side, far seemed to outweigh [it]. The darkness came into his music a lot. And without it, what would that music have been?”

All those sides of Garcia — musically and internally — emerge in this collection of the 50 greatest songs that he performed with the Dead and from his solo records.

From Rolling Stone US